Chess and art have shared a close relationship virtually since the invention of the game.

Throughout the long and rich history of chess, the three-dimensional playing pieces have provided artists and craftsmen with seemingly endless opportunities for creative interpretation and expression, resulting in a tremendous diversity of forms ranging from the representational to the abstract. Within the standardized arrangement of thirty-two pieces on the square grid of the game board, artists have found innumerable ways to challenge expectations with innovative approaches, transforming this timeless and universal game into something novel and even unconventional. While the material aspects of chess, such as the pieces and board, have traditionally been the focus of artistic expression, a number of more recent artists have directed their creative energies not toward the game as a static arrangement of objects, but toward the strategic nature of the chess match as a complex mental process.

OUT OF THE BOX: Artists Play Chess is an exploration of artworks that consider chess both at the formal level and at the level of actual play.

Comprising a wide breadth of media, these artworks demonstrate an integration of chess that goes beyond the visual, incorporating elements of play or strategy that invite the viewer to reflect on the game’s intricate operations. The theme of this exhibition will remind many of the chess-inspired strategic maneuvers of one of the twentieth century’s most respected and controversial artists, Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), whose intellectual depth, ironic wit, and playful spirit are echoed in the similarly challenging, irreverent, and quixotic works in this gallery. These artworks demonstrate how the nature of the game complicates and enriches static media such as sculpture, or time-based media such as video, and draws the spectator into the work in a way that is truly inimitable to chess.

On View: September 9, 2011 – February 12, 2012

Works Featured in the Exhibition

Tom Friedman, Untitled, 2005

Tom Friedman (American, born 1965)

Untitled, 2005

Pieces: mixed media; table and board: maple and American black walnut; wall mounts: maple, American black walnut, and Perspex

Edition 6 of 7

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

Upon first glance, native Saint Louisan Tom Friedman’s chess set is as baffling as it is charming, as the spectator almost immediately recognizes the principal dilemma: that no two pieces on the board are the same. Without the ability to identify the type and available moves of each piece on the board, the set teeters on the very brink of functionality, a tension that is typical of Friedman’s work. A clever assemblage of found objects and meticulously crafted items possessing qualities that are both universally known and intensely personal, the wall-mounted chess-piece cases, table, and stump-like chairs fit snugly into their severely geometric wooden box, which presents a minimalist solidity and sobriety that contrasts strongly with its whimsical contents. The diminutive sculptural pieces recall the themes and concepts that Friedman has explored throughout his career, particularly the increasing intersections between art and everyday consumer culture and the rapidly diminishing distinctions between public and private in contemporary life.

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Do you feel comfortable losing?), 2006

Barbara Kruger (American, born 1945)

Untitled (Do you feel comfortable losing?), 2006

Pieces: black and red Corian, miniature speakers, electronic and computer components; box and board: sublimated image in Corian, electronics, and customized metal and carbon fiber flight case with printed exterior and foam interior. From an edition of 7 and 3 artist’s proofs

Luhring Augustine, New York

Famous for her singular style that developed out of her background as a graphic designer and art director in the magazine publishing industry, Barbara Kruger uses the conventional interactivity of a chess match as a metaphor for the complex exchanges that take place during verbal communication. The basic concept of this chess set can be understood as a visualization of the theories of Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, particularly his use of the terms langue (“language”) and parole (“speech”) to distinguish between the impersonality of the written word and the individuality and subtlety of spoken language. When a piece is moved into a position, a microchip is triggered that randomly plays through a small speaker one of over one hundred possible statements, which are also printed on the set’s flight-case-style box in her signature Futura Bold Oblique typeface. With each match promising a unique exchange of phrases, the “conversation” mirrors not only the virtually limitless number of possible move sequences in a chess match, but also the vast number—and seemingly random interactions—of slogans, headlines, and sound bites seen and heard every day in the mass media.

Liliya Lifánova, Anatomy is Destiny: The Wardrobe, Game in Waiting, 2009.

Liliya Lifánova (American, born in Kyrgyzstan, 1983)

Anatomy is Destiny: The Wardrobe, Game in Waiting, 2009

Mixed-media installation. Collection of the artist

Choreographer: Davy Bisaro

Sound designer: Sebastian Alvarez

The title Anatomy is Destiny, a direct reference to the psycho-theory of Sigmund Freud, invokes the highly controversial theories that form the foundation of the psychosexual development of young boys and girls known as the Oedipus complex. This work consists of two components: the installation of garments called The Wardrobe: Game in Waiting seen here, and the full-scale performance in which performers don the garments and execute the moves of an imaginary chess match between Marcel Duchamp and his infamous female alter ego Rrose Sélavy that was envisioned by the artist Arman in 1972. Inspired by a diverse array of historical military fashions and constructed of linen backed with cotton, each garment in the wardrobe was designed by Lifánova to restrict the movement of the performer in such a way that approximates the respective movements of that piece on the game board. The performance of Anatomy is Destiny seen in the video was presented at the Episcopal Church of the Epiphany in Chicago on September 11, 2009.

The World Chess Hall of Fame presented Liliya Lifánova’s performance art piece, Anatomy is Destiny, at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, February 15, 2012.

Yoko Ono, Play It by Trust (Roskilde Version), 2002

Yoko Ono (Japanese, born 1933)

Play It by Trust (Roskilde Version), 2002

Wood chairs, table, and chess pieces

Edition 3 of 6

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

Starkly beautiful in its austere appearance and its unflinchingly straightforward concept, artist and longtime peace activist Yoko Ono’s all-white chess set Play It by Trust marries the spare, geometric lines of Minimalism with the intimate, playful interactivity of the games produced by the members of Fluxus, an international avant-garde movement with which Ono was associated in the 1960s. Originally conceived as the White Chess Set in 1966, Play It by Trust was born of a tumultuous era characterized by the Cold War tensions of the nuclear arms race, the military conflict in Vietnam, and the struggle for civil rights in the United States. As the players are forced into ever-greater reliance on each other to identify which piece belongs to which player as the game progresses, Ono elegantly recontextualizes a game that is normally thought of as a microcosmic allegory of war, emphasizing collaboration over competition and empathy over opposition.

Diana Thater. Georges Koltanowski vs. Marcel Duchamp, Paris, 1929 (Played by Ellen Simon and Cybelle Tondu), 2010

Diana Thater (American, born 1962)

Georges Koltanowski vs. Marcel Duchamp, Paris, 1929 (Played by Ellen Simon and Cybelle Tondu), 2010

Installation for 4 video monitors, 1 Blu-ray player, 1 Blu-ray disc

Certificate THADI0156

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

Diana Thater’s belief that abstraction can exist in representational moving images is effectively demonstrated in her video installation Georges Koltanowski vs. Marcel Duchamp, Paris, 1929. Displayed over four monitors arranged to form a rudimentary grid that reiterates the rigid geometry of the chessboard, the disembodied hands nimbly execute the predetermined moves that, over a period of extended viewing, blur into subtly hypnotic rhythms. While Thater is customarily known for using brilliant, highly saturated colors in her work, her chess-inspired videos are dominated by the stark black-and-white presentation of the board and the classically inspired Staunton chessmen familiar to novices and tournament players alike. Having already re-enacted such iconic games as the so-called Immortal Game between Adolf Anderssen and Lionel Kieseritzky in 1851 and Garry Kasparov’s famous bout with the chess computer Deep Junior in 2003, Thater chose to commemorate artist-turned-chess master Marcel Duchamp’s stunning upset of the Belgian champion Georges Koltanowski in only fifteen moves in 1929, which can perhaps be interpreted as an argument for the power of imagination and creativity over technical mastery.

Gavin Turk. The Mechanical Turk, 2008.

Gavin Turk (British, born 1977)

The Mechanical Turk, 2008

HD film on DVD

RS&A Ltd., London

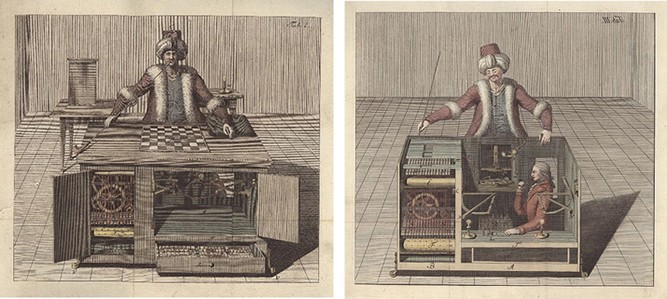

British artist Gavin Turk draws on the postmodern view of identity as fluid and unstable, recasting himself as the diverse contingent of artists, cultural icons, and media darlings (Andy Warhol, Elvis Presley, Che Guevara, Sid Vicious, and Joseph Beuys, among others) whose towering presences comprise his understanding of celebrity. In The Mechanical Turk, Turk reinvents himself as his erstwhile namesake, the Mechanical Turk or the Automaton Chess Player, which, following its introduction in 1770, achieved tremendous fame in Europe and the United States until it was exposed as a fraud in the 1820s. Able to defeat even the most skilled players thanks to a host of chess masters who secretly operated the machine from within, the Mechanical Turk was also capable of performing the knight’s tour, an extremely difficult chess puzzle in which the player moves a knight in a sequence such that each square on the board is occupied once without repeat. Executing the knight’s tour in the video with machine-like precision and efficiency, Turk becomes the embodiment of our dual fascination with artificial intelligence and theatrical showmanship.

The Mechanical Turk, or the Automaton Chess Player

While not truly artificial intelligence, the “automaton” remains the ancestor not only of such celebrated chess computers as Deep Blue and Deep Junior, but also of all game-playing computers, including the trivia mastermind Watson recently featured on Jeopardy!. Devised by the Hungarian inventor Baron Wolfgang von Kempelen, the Mechanical Turk rose to instantaneous renown after it was introduced at the Viennese court in 1770. Using a clever system of false doors, dummy mechanisms, and visual misdirection, von Kempelen was able to convincingly show the “inner-workings” of the machine without revealing the chess master hidden inside, who operated the Turk through an elaborate arrangement of levers and magnets. The Turk racked up a substantial list of victories against some of the best players in Europe before the death of von Kempelen in 1804, after which it was sold to Johann Maelzel, who continued to tour the Turk throughout Europe and later the United States. Not surprisingly, many were skeptical of the authenticity of the Turk upon its debut, writing sensational essays revealing what they believed to be the machine’s actual operations, the most famous of which was penned by Edgar Allen Poe in 1836. The true secret of the Turk was finally revealed by the son of its last owner in an article published three years after the machine was destroyed in a fire in Philadelphia in 1854.

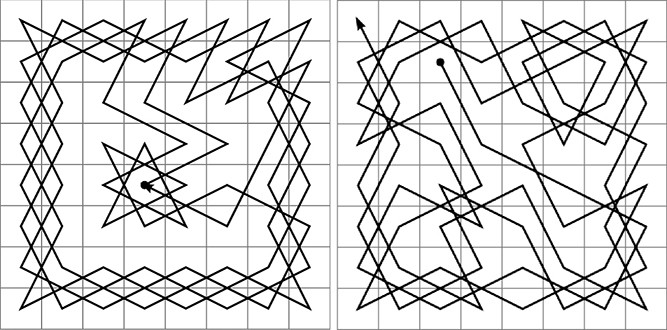

Diagrams illustrating the knight

Joseph Friedrich Freiherr von Racknitz’s famous illustrations from his 1789 book about the Turk showing his incorrect theory of how the human chess player was concealed within the cabinet.

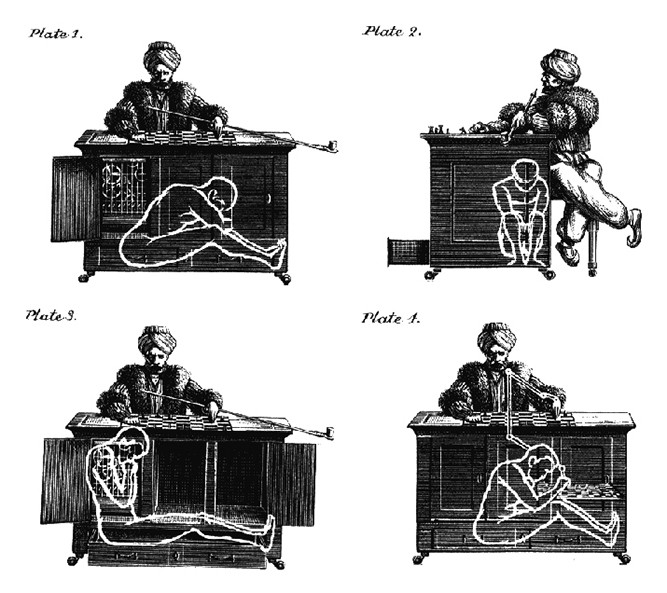

Plates from Ernest Wittenberg’s article “Échec!” that appeared in American Heritage magazine in 1960 more accurately show how the machine’s director remained hidden when various sections of the interior were revealed, as well as how the Turk’s arm was operated using a type of mechanical linkage called a pantograph.

Guido van der Werve, Number Twelve: Variations on a Theme, 2009

Guido van der Werve (Dutch, born 1977)

Number Twelve: Variations on a Theme, (the king’s gambit accepted, the number of stars in the sky, and why a piano can’t be tuned, or waiting for an earthquake), 2009

Chess piano: walnut, ebony, fichte, maple, piano mechanism; wood chess pieces and stools

Photographs: Digital C-print

Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Juliette Jongma, Amsterdam, Marc Foxx, Los Angeles, and Luhring Augustine, New York

In order to play his lushly orchestrated composition Number Twelve, artist and composer Guido van der Werve designed his own instrument, a hybrid chessboard and piano. When a player makes a move, the piece is pressed into the chosen square, triggering a hammer to strike a string as with a traditional piano. The orchestration was built around a chess game composed by Russian Grandmaster Leonid Yudasin, which also functions as a musical score for the chess players. Another component of the work is a film that begins with van der Werve and Yudasin playing the chess piano with a chamber orchestra at the Marshall Chess Club in New York City, followed by a series of aerial shots of the artist amidst landscapes as lush and lyrical as their musical accompaniment. Each photograph presented here is a still from the film, with a chess diagram below the smaller photos to indicate the position in the score that accompanies the image. In the Romantic tradition, van der Werve’s interweaving of music, film, and photograph straddles the personal and the universal, uniting the directness of musical expressivity with the epic totality of nature.

OUT OF THE BOX: Artists Play Chess is curated by Dr. Bradley Bailey, assistant professor of modern and contemporary art history at Saint Louis University and coauthor of the book Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Chess (Readymade Press; Distributed Art Publishers). In 2009 he curated the exhibition “Marcel Duchamp: Chess Master” for the Saint Louis University Museum of Art, and was co-curator of “Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Chess” at Francis M. Naumann Fine Art in New York.

Generous support for OUT OF THE BOX: Artists Play Chess was provided by Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield and the Mondriaan Foundation, Amsterdam.

Special thanks to our lenders Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield; Liliya Lifánova; Luhring Augustine, New York; RS&A Ltd., London; Galerie Juliette Jongma, Amsterdam; and Marc Foxx, Los Angeles.

Press

3/2012: ARTnews — Pawn Stars

11/22/11: STLMag.com — Out of the Box: Artists Play Chess at the World Chess Hall of Fame

11/9/11: ChessBase News — World Chess Hall of Fame opens in St. Louis,

10/20/11: Riverfront Times — Out of the Box: Artists Play Chess

10/10/11: ArtDaily.org — World Chess Hall of Fame Exhibition Explores Relationship between Art and Chess

9/12/11: STL Beacon — World Chess Hall of Fame plans new strategy with opening in St. Louis

9/9/11: St Louis Magazine — Best Chess in the West: Rex Sinquefield’s World Chess Hall of Fame Opens in CWE

9/8/11: Temporary Art Review — Fall Out Guide

9/1/11: Riverfront Times — Check Out This Move

9/2011: St. Louis Magazine — Endgame: St. Louis Moves Towards Chess Domination.