Her Turn: Revolutionary Women of Chess celebrates the legacies of many of the game’s greatest female players.

On View: February 4 – September 4, 2016

Her Turn highlights the stories of a diverse number of women chess players from the late nineteenth through the early twenty-first centuries. The 1897 International Ladies’ Chess Congress, organized by the Ladies’ Chess Club of London and held in conjunction with Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, was the first international women’s competition. Thirty years later, London also hosted the first Women’s World Chess Championship, which was won by one of the early superstars of women’s chess, Vera Menchik. Through her example, Menchik, the first woman inducted into the World Chess Hall of Fame, paved the way for generations of female players to come. Meanwhile, in the United States, a trio of talented players—Adele Rivero, Mona May Karff, and Gisela Gresser—dominated early U.S. Women’s Chess Championships. Some of these women faced difficulties in their early careers—both Mona May Karff and 1951 U.S. Women’s Chess Champion Mary Bain recollected not being allowed into chess clubs because of their gender.

Her Turn explores the stories of these early pioneers as well as later trailblazers who overturned gender stereotypes in chess, including the Polgar sisters—Susan, Sofia, and Judit. Through this display, Her Turn not only explores some of the struggles that female chess players faced over generations but also celebrates their accomplishments as players, organizers, and writers. Through this display, the World Chess Hall of Fame hopes both to not only educate our visitors about a sometimes overlooked aspect of chess history, but also inspire more women to take up the game.

From the Curator

Her Turn: Revolutionary Women of Chess examines women’s chess history through highlights from the collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame as well as loans from the John G. White Chess Collection at the Cleveland Public Library and numerous private collections. The photographs and other artifacts included in this show tell stories about women chess stars, both in the United States and worldwide.

Her Turn is part of an effort by the Saint Louis Chess Campus to attract more girls and women to the game. On October 29, 2015, the World Chess Hall of Fame opened Ladies’ Knight: A Female Perspective on Chess, which explores the game through the imaginations of a group of spectacular contemporary artists including Rachel Whiteread, Yoko Ono, and Barbara Kruger. These artists used the lens of chess to examine a variety of issues—from questions of justice in Yuko Suga’s Checkmate: Series I Prototype (2015) to standards of beauty in Debbie Han’s Battle of Conception (2010). Soon after the opening of this exhibition, the Chess Club and Scholastic Center revamped its beginner chess classes aimed at women.

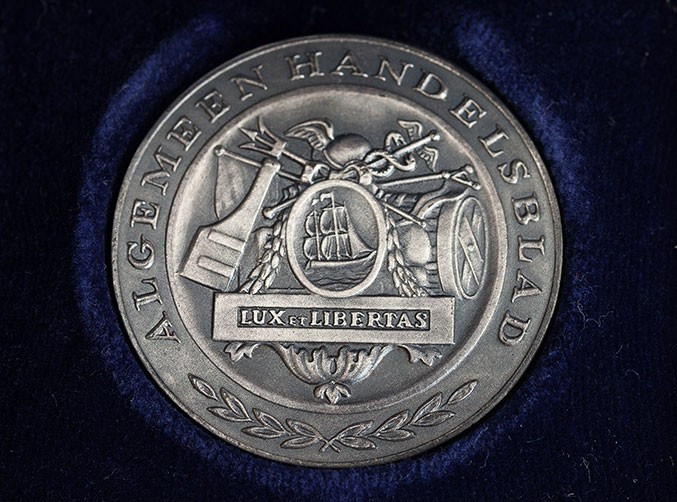

Like its companion exhibition Ladies’ Knight, Her Turn presents a variety of perspectives in an effort to show the diverse history of women chess players from the late nineteenth through early twenty-first centuries. It includes artifacts related to early pioneers like Vera Menchik, the first Women’s World Chess Champion and the first woman to be inducted into the World Chess Hall of Fame; Georgian superstars like Nona Gaprindashvili and Maya Chiburdanidze; and Susan, Sofia, and Judit Polgar, among many others. The exhibition also presents artifacts related to important moments in women’s chess history, including nine-time U.S. Women’s Chess Champion Gisela Gresser’s medal from the first Women’s Chess Olympiad, Susan Polgar’s 1996 Women’s World Chess Championship Trophy, and Alexandra Kosteniuk’s medal from the 2008 Women’s World Chess Championship, as well as many photographs depicting tournaments.

Menchik, Gaprindashvili, and Chiburdanidze are three of the six women currently inducted into the World Chess Hall of Fame. The others are Soviet Women’s World Chess Champions Elizaveta Bykova, Olga Rubtsova, and Lyudmila Rudenko. Her Turn also includes artifacts related to the legacies of the female members of the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame: Gisela Gresser, Diane Savereide, Mona May Karff, and Jacqueline Piatigorsky. The stories of a variety of players, writers, and organizers are also presented in the exhibition.

As part of Her Turn, the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis will also host an installation of photographs, score sheets, and other artifacts related to the U.S. Women’s Chess Championships, which the organization has hosted since 2009. Through sharing the inspiring stories of these women, we hope to encourage more girls to take up the game and share this sometimes overlooked history with our visitors.

—Emily Allred, Assistant Curator

Photo by Michael DeFilippo

Ruth Haring on Chess: 1974-1984

In 1969, I started playing in chess tournaments at age 14 after my family moved to Arkansas for my father’s new position as the Head of Graduate Studies at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. In my new middle school, friends introduced me to the world of tournament chess. This was the era in which American chess grew and became more popular, as Bobby Fischer was rated over 2700 and on his way to becoming World Chess Champion. Part of the “Fischer boom,” his success on the world stage inspired me, and I vowed to improve, participating in as many competitions as possible. In the 1960s and 1970s, there were no computers or chess engines and few afterschool chess programs or coaches and trainers. One learned the game primarily through reading books and magazines and through the experience achieved during over-the-board play. My dad soon realized I was serious about the game and bought me a life membership in the United States Chess Federation (then the USCF, now US Chess) and gave me a Chess Informant for Christmas. Though the story of how I first became interested in chess is surprisingly similar to others of my generation, it would lead to interesting adventures, first as a player in national and international tournaments, and later as a president of the United States Chess Federation Board of Directors.

As a freshman in college, I was surprised to be invited to the 1974 U.S. Women’s Chess Championship as the alternate. Though seeded last with a 1757 rating, I finished the tournament undefeated, and placed second with a score of 7.5-2.5, a half of a point behind Woman International Master and seven-time U.S. Women’s Chess Champion Mona May Karff of New York. I would go on to play in every U.S. Women’s Chess Championship between 1974 and 1984, placing second in 1979’s tournament with a score of 8.5-2.5.

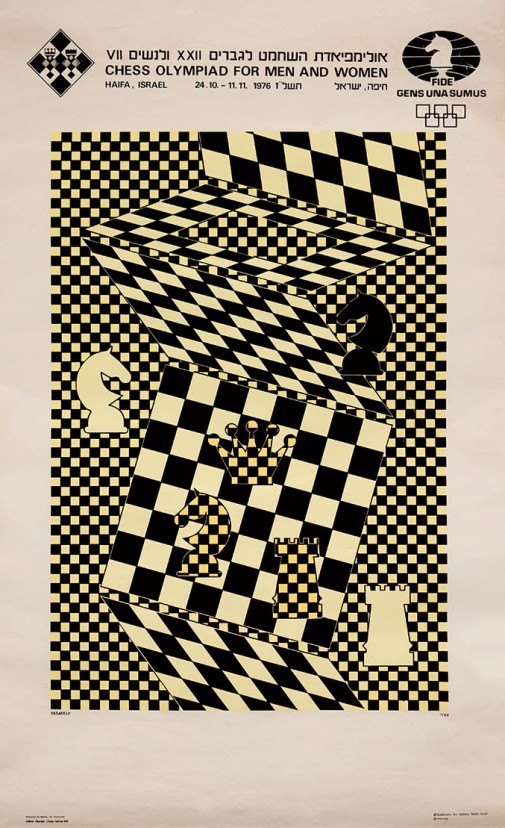

After my first U.S. Women’s Chess Championship, I competed in a number of top level tournaments both in the United States and abroad. From 1974 to 1982, I competed in a total of five women’s Olympiads. I achieved one of my best performances in the 1976 Olympiad in Haifa, Israel, scoring 5-3 as the reserve player to win an individual bronze medal.

Earlier that same year, I competed in my first real international competition, the Interzonal Tournament in Roosendaal, The Netherlands, and I scored 5-8. This included a draw with the tournament winner and future Women’s World Chess Championship challenger Woman Grandmaster Elena Akhmilovskaya Donaldson, then playing for the Soviet Union. In the 1980 Malta Olympiad, I was the top scorer for the U.S. women’s team, earning a score of 7.5-4.5 on Board Three. In this competition, I played 12 rounds! In October 1980, I won an international women’s tournament in Thessaloniki, Greece, with a score of 8-1—going undefeated. With this victory, I became the first American woman to win an international round robin norm tournament. I played chess because I loved the game, the camaraderie, and the competition. As a teen and young adult, I played thousands of games in every tournament event possible in both the United States and Canada on most weekends for 17 years. To support myself, I worked as a law clerk in San Francisco. Playing tournament chess brought many advantages to me, but money was not one of them. However, chess enabled me to travel throughout the United States and make friends everywhere.

In the beginning, when I qualified for an international women’s event, it felt like I had won the lottery. I received an all-expense paid trip to a city, sometimes even overseas, in return for being myself and doing something I loved to do. These tournaments, in faraway and sometimes exotic places, were great learning experiences for a young woman. I am grateful that the USCF supported women’s events at that time.

Interestingly, I did not view myself as a “woman chess player” but just a “chess player,” and considered myself lucky to be eligible for events that ultimately changed my life through the learning that travel and meeting people brings. Still, it was never an option for me to become a “professional chess player,” nor did I consider it. For example, the prize fund at the 1976 U.S. Women’s Chess Championship was $1050 with a first prize of $300. I tied for second and won a prize of $175.

Though I am telling much of my story through the lens of women’s events, I played in many more USCF weekend Swiss tournament games during that era than women’s events. The majority of my games were in fact played against men, as a “weekend warrior.” In 1977, while rated 2043, I scored a victory over International Master (IM) John Peters, rated 2476. The bulletin from the tournament notes that Peters was experiencing a winning streak noting, “Prior to the following game John Peters had a 10-0 tournament game result in Arizona which resulted from his 4-0 finish in the 1976 Summer Chess Festival (in which he defeated Grandmaster Larry Christiansen to tie with Grandmaster James Tarjan for first), the 1977 Grand Canyon Open, and the first round game above. None of his last six games, all against expert level competition, lasted over 28 moves.”

Ruth Haring – John Peters

1977 Del Webb’s Townhouse Summer Chess Festival, Phoenix, Arizona

1. e4 c5 2. c3 d5 3.ed Qd5 4. d4 e6 5. Nf3 Nc6 6. Be2 cd 7. cd Nf6 8. Nc3 Qd6 9. 0-0 Be7 10. Be3 0-0 11. Qd2 b6 12. Rad1 Nb4 13. Ne5 Bb7 14. Bf4 Qd8 15. Bg3 Rc8 16. Rfe1 Nbd5 17. Nd5 Nd5 18. a3 Bg5 19. Qd3 Bf4 20. Bf3 Bg3 21. hg Qc7 22. Be4 Nf6 23. Bb7 Qb7 24. g4 Nd5 25. Re4 Qe7 26. Nf3 Rfd8 27. Rde1 Qc7 28. Ne5 Qc2 29. Qf3 Rc7 30. R4e2 Qa4 31. Rd2 f6 32. Nd3 Qd4 33. Red1 Ne7 34. Nf4 Qd2 35. Rd2 Rd2 36. Ne6 Rcc2 37. Qa8+ Nc8 38. Qb7 1-0

This nomadic kind of life, with a consuming focus only on chess, was fun but not sustainable, so in 1983 I decided to pursue a career in Silicon Valley. I went back to school and took programming classes and used this new training and my earlier degree in psychology to earn a job at TRW Inc., a company in Santa Clara California. I worked as a technology professional in Silicon Valley moving on to IBM, Lockheed Martin, and eBay. My new career marked the end of an era in my life as my focus began to change, and I played in fewer and fewer chess events, finally ceasing to play in tournaments in 1985. In 1986 my eldest daughter was born and my top priorities officially became my family and career.

A new chapter in my chess adventure began in 2008, when I returned to chess after a 23 year hiatus, and took my son to his first tournament, the U.S. Open in Dallas, Texas. Upon my return, I learned that there was an election for the Executive Board of the US Chess Federation, and that there were serious organizational issues to be solved. This inspired me to give back to the organization that had supported me as a young woman and afforded me the opportunity to travel worldwide and play chess. I felt fortunate that my chess experiences had helped me to become a successful businesswoman. I ran for the USCF Executive Board and won in 2009 and subsequently served as Vice President for two years. I was selected as President of the Board and served from 2011-2015 and am currently serving my last year as a member of the Board of Directors. During my tenure as President of the Board, I emphasized increasing US Chess Federation membership, and this included studying issues related to attracting girls to the game and retaining female members.

Through this work, I have often been asked why women are not rated at the same level that men are at chess. This is a complex question with many cultural and societal variables. However, if you examine the numbers of women playing compared to men, it becomes obvious that the reason women do not achieve higher ratings is that there are not enough women in the population of tournament players to make that a statistical reality. For example our scholastic programs sometimes have up to 20% girls, but they drop out at puberty. Among adults the female playing population varies from 7% to 4%, declining as age increases. Thus I believe that the best way to achieve the goal of parity with male players is to encourage play among girls. When the populations are equal in numbers this problem will disappear and hopefully afford the same opportunities that I received to a new generation of female players.

—Woman International Master Ruth Haring, past President of the Board of Directors United States Chess Federation

Photo by Michael DeFilippo

Georgian Chess Heroes

Georgia has always held a special place in the chess world. Its women have been especially strong, having once held the Women’s World Chess Champion title for just under 30 consecutive years. The first pioneer and a phenomenal success of women’s chess in Georgia was Nona Gaprindashvili, who in 1962 became the Women’s World Chess Champion at the age of 21. A five-time world champion, Nona helped to propel the Soviet Olympiad team to 11 team gold medals during her tenure. During this impressive run, she managed to earn an astounding nine individual gold medals. She is also the first woman in chess history to earn the prestigious grandmaster title. Nona’s success inspired generations of Georgians and thousands of chess players worldwide. She was an idol to her fans and held such popularity amongst young girls that parents began naming their daughters Nona in her honor. They also signed up their children for chess lessons in record numbers.

Nona carried celebrity status and was recognized on the streets just as easily as any Hollywood actor. She was indeed a national hero and influenced fellow Georgian stars like Maya Chiburdanidze, Nana Aleksandria, Nana Ioseliani, Nino Gurieli, Ketevan Arakhamia, and Ketevan Kakhiani.

Nona Gaprindashvili held her title until 1978 when she was dethroned by the above mentioned Maya Chiburdanidze. As a child, Maya kept a picture of Nona hanging on her wall and actually beat her for the first time during a simultaneous exhibition when Maya was only 13. She kept her Women’s World Chess Champion title for 13 consecutive years, often defeating fellow Georgians vying for the title.

During Nona’s and Maya’s reigns, Georgia was still part of the Soviet Union. The then U.S.S.R. teams completely dominated world events and were comprised of many Georgian players. Once the U.S.S.R. broke, an independent Georgia took three consecutive gold medals during the 1992-1994 and 1996 Olympiads. Their most recent win was at the 2008 Olympiad held in Dresden, Germany. The team was anchored by Maya Chiburdanidze, Nana Dzagnidze, Lela Javakhishvili, Maia Lomineishvili, and Sophio Khukhashvili. During that competition, Maya Chiburdanidze added another individual gold medal to her record by posting a 2707 performance rating.

Nona Gaprindashvili’s love for the game and her fighting spirit continues to amaze many chess players around the globe. She has won four Senior World Chess Championships in 1995, 2009, 2014, and 2015. The latter two victories were in the over 65 division.

Chess in various forms was first introduced in Georgia in the seventh and eighth centuries. Since then chess has often been found in Georgian literature and poetry. Traditionally, when Georgian women got married their parents would give them chess sets as part of their wedding presents. Chess continues to be the most popular sport in Georgia. Many young players still win medals at the World Junior Championships each year. Most recently the Georgian National team won the Women’s World Team Championship in 2015. Currently, Nana Dzagnidze, Lela Javakhishvili, Bela Khotenashvili, and Nino Batsiashvili are all on the list of top 20 female players.

It is hard to explain the success of women from my home country other than to say that perhaps we were lucky to be born in a country where we take in chess with our first breath. We see our parents and relatives play with great enthusiasm and have a steady stream of female role models to inspire us. Whenever I return home, I feel my rating and chess understanding increase the moment I touch Georgian soil.

—International Master Rusudan Goletiani, 2005 U.S. Women’s Chess Champion

Interview with 2008 Women’s World Chess Champion Alexandra Kosteniuk

When did you first take an interest in chess?

My father taught me to play chess at the age of five. I don’t remember whether I was fascinated by the game from the very first games I played, but definitely I had some talent and most important perseverance and ability to concentrate on chess for a long time. It first brought victories in children’s tournaments and after that, little by little, I made my road to the world of chess.

What players were inspirations to you early in your career? Were there any women chess players whom you viewed as role models?

I have never had any role models, not only in chess but in anything else. I admire and respect people who reached certain heights in their professions but I can’t say that I had a role model.

In addition to being the twelfth Women’s World Chess Champion, you are a writer who has published books about your accomplishments. What are some of the most memorable moments of your career?

Every victory is a memorable one. There are no easy victories, and there are a lot of emotions, struggle, and work hidden behind every single game. So when I look at the results of my career I can’t say that I have the most favorite or memorable tournament. Of course winning the 2008 Women’s World Chess Championship, was a special victory, but, for example, every single Chess Olympiad gold is as special for me as the victory in Nalchik.

What was your favorite game of the 2008 Women’s World Chess Championship? Could you provide analysis of a position from it?

In my book Diary of a Chess Queen, I described the first game of the final match of the 2008 Women’s World Chess Championship. In it I wrote:

And so, here I was, seven years later, playing another title match. A lot had changed in my life in those seven years. I had played at least a couple of hundred tournament games, attended over fifty training sessions, won perhaps a thousand games in simultaneous exhibitions, given innumerable interviews, made my film debut, given my first public speech, written two books, graduated from the university, gotten married—and most importantly, given birth to a wonderful baby, who was now back in Moscow, rooting for her Mama throughout the whole match. I’d had to go through thick and thin to get a second chance to fight for the chess crown. For my encounter with Hou Yifan, in contrast to the final match in 2001, now it was my opponent who played the role of the underdog, as she was only 14! The final match was under control from start to finish. In nearly every game, I had winning chances. The number of unconverted extra pawns in this match probably broke all records. In the first game, I managed to win with Black; and in the end, that proved decisive.

As a chess promoter, what do you see as some of the challenges to getting more girls and women to take up chess and how can they be overcome?

I think the challenges in order to attract girls and women into chess are similar to the challenges that other “non-female” professions have. There are not so many girls (compared to the number of boys) who wish to connect their life with physics or mathematics, going into space, or playing soccer. The answers to this issue are mostly in our social environment and in the way nature created men and women. In order to overcome these obstacles in chess, we have to create more girls-friendly clubs and programs and support girls on their way to reach new chess heights.

U.S. Women’s Chess

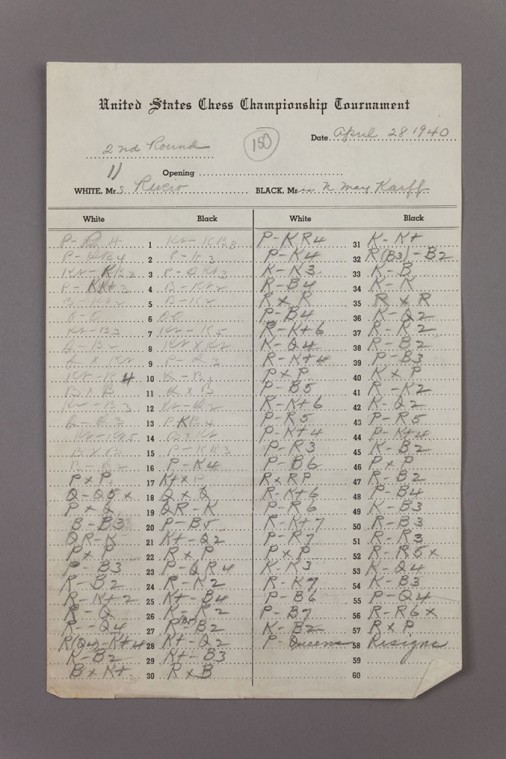

Score sheet from the 1940 New York City, New York, U.S. Women’s Chess Championships—Adele Rivero vs. Mona May Karff

April 28, 1940

10 7⁄8 x 7 in.

Score sheet

John G. White Chess Collection at the Cleveland Public Library

During the late 1930s and early 1940s, Adele Rivero and Mona May Karff were two of the United States’ most prominent women players. Rivero, who would later become the 1940 U.S. Women’s Chess Champion, proved victorious in this game, in which she played as white. Of it, the chess columnist for the New York Times wrote, “The two were well-matched and reached an ending with two rooks and even boards on each side. When one of the rooks was exchanged, Mrs. Rivero obtained an advantageous post for her king and this decided the issue after 57 moves.”

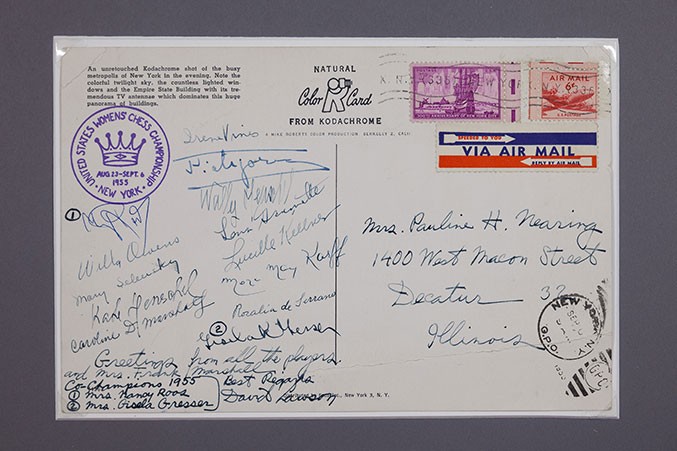

Autographed Postcard from the 1955 New York City, New York, U.S. Women’s Chess Championship

1955

6 x 9 in.

Postcard

Collection of Richard Benjamin

This postcard bears the signatures of each of the participants in the 1955 U.S. Women’s Chess Championship, including co-winners Gisela Gresser and Nancy Roos. Mona May Karff finished just a half point behind the pair, in part due to a loss to Jacqueline Piatigorsky, who won the competition’s brilliancy prize for her win over Karff in the tournament. Caroline Marshall, the wife of 1986 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Frank Marshall, also signed the card. She served as a key organizer of early U.S. Women’s Chess Championships and also was the manager of the famous Marshall Chess Club in New York.

Chess Review Vol. 9, No. 9

November 1941

10 x 7 in.

Periodical

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Pictured on the cover of the November 1941 issue of Chess Review is Adele Rivero, who was the 1940 U.S. Women’s Chess Champion. Though the 1940 Championship was held as a tournament, Rivero agreed to defend her title the following year in a match against a single opponent, Mona May Karff. Sponsored by Chess Review, the match was held in at least five different locations, with games being played at the home of the Vice President of the United States Chess Federation Walter Stevens, the Manhattan Chess Club, and the Queens Chess Club, among other locations.

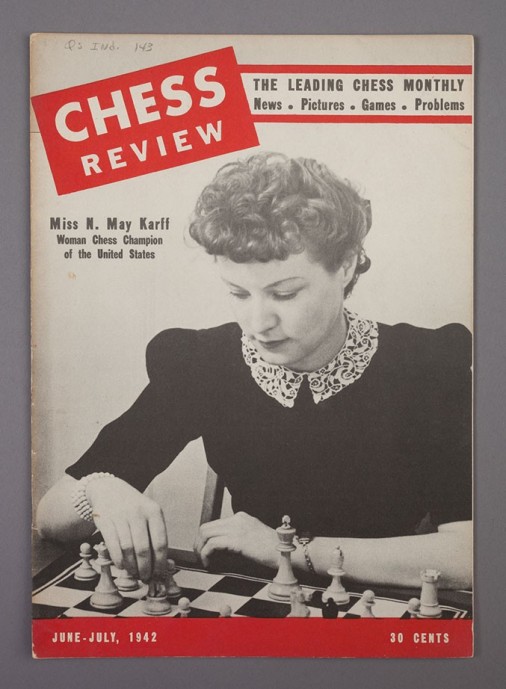

Chess Review Vol. 10, No. 6

June-July 1942

10 x 7 in.

Periodical

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

In 1942’s U.S. Women’s Chess Championship, Mona May Karff was unbeatable. The championship returned to a tournament format that year, featuring nine competitors, including rival Adele Rivero, Gisela Gresser, Nancy Roos, and Mary Bain. Karff finished the tournament, which was held concurrently with the “men’s” championship, undefeated with a score of 8-0.

Chess Review Vol. 12, No. 5

May 1944

10 7/8 x 8 1/2 in. Periodical

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Though Gisela Gresser had competed in the U.S. Women’s Chess Championships since 1940, 1944 was the first year in which she triumphed over the field, finishing the tournament undefeated. Gresser would go on to a long career in chess, winning nine U.S. Women’s Chess Championships, competing in the 1949/50 Women’s World Chess Championship tournament, and representing the United States at the first women’s Chess Olympiad in 1957.

Trophy from the Mary Bain Memorial United States Women’s Open Chess Championship

c 1972-1973

20 x 5 3/8 x 5 1/2 in.

Trophy

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

1951 U.S. Women’s Chess Champion Mary Bain was devoted to the game. Following her win in that Championship, she embarked on a tour of the United States in which she conducted simultaneous exhibition matches in chess clubs around the country. Bain used the publicity that she gained from taking on opponents, both male and female, to promote the game in interviews. An April 28, 1952, article in the Milwaukee Journal reported her statement that, “‘In this country only’ men chess players never believe a woman can attain their level. In her case this attitude has been more or less a challenge. She is finding the exhibitions, in which she plays against a number of men, pleasantly stimulating.” During the 1950s, she also founded her own chess studio in New York. Bain died in 1972, and this U.S. Women’s Open Chess Championship trophy was created in her honor. The U.S. Women’s Open was held alongside the U.S. Open Chess Championship through 1973, though it was revived for one year in 2009.

Artifacts Featured in the Exhibition

U.S. Women’s Chess Championships

Crosstable from the 1967 New York City, New York, United States Women’s Chess Championship

1967

8 1/2 x 11 in.

Document

Collection of The World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

Held from April 29-May 5, 1967, at the Henry Hudson Hotel, the 1967 United States Women’s Chess Championship marked Gisela Gresser’s eighth victory in the competition. Her ninth and last win in the tournament would be in 1969. Gresser’s record number of U.S. Women’s Chess Championship victories has not been surpassed. On one side, this document pictures a hand-drawn crosstable of the event, and on the reverse, the schedule of the rounds. Many of the competitors in the 1967 championship had been participating in the tournaments since the 1930s and 1940s. In her July 1967 Chess Life article about the event, Kathryn Slater described it as a “tournament of veterans.”

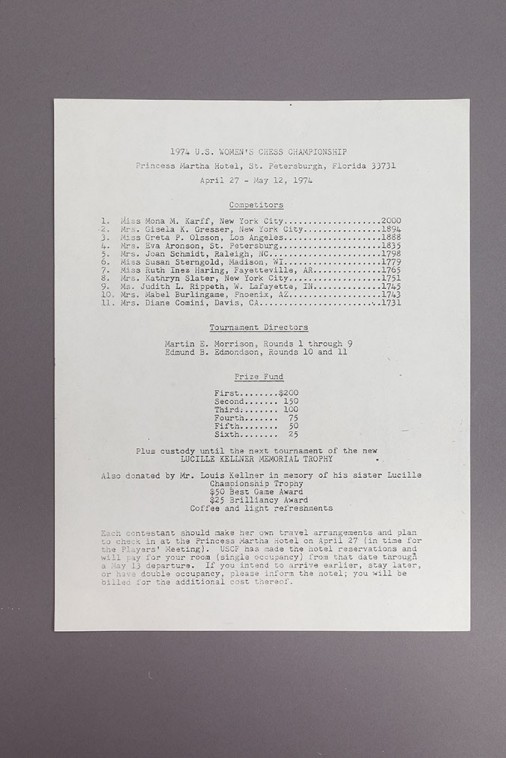

List of Competitors and Prizes from the 1974 St. Petersburg, Florida, U.S. Women’s Chess Championship and Ladies’ Zonal Tournament

April 27 – May 12, 1972

11 x 8 1/2 in.

Document

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

The 1974 U.S. Women’s Chess Championship was a Zonal Tournament in which its top two players qualified for the Interzonal, a part of the Women’s World Chess Championship cycle. Eva Aronson, who was the chairwoman of the United States Chess Federation’s Women’s Chess Committee, an organization that oversaw the organization of national women’s events, won the 1974 tournament. Though Aronson had long been involved with women’s chess events, the tournament director Bob Braine noted that the competition marked “a new era in women’s chess.” He described the challenges that Gisela Gresser, who had long been the top American women’s player, faced against a field that included five first-time competitors.

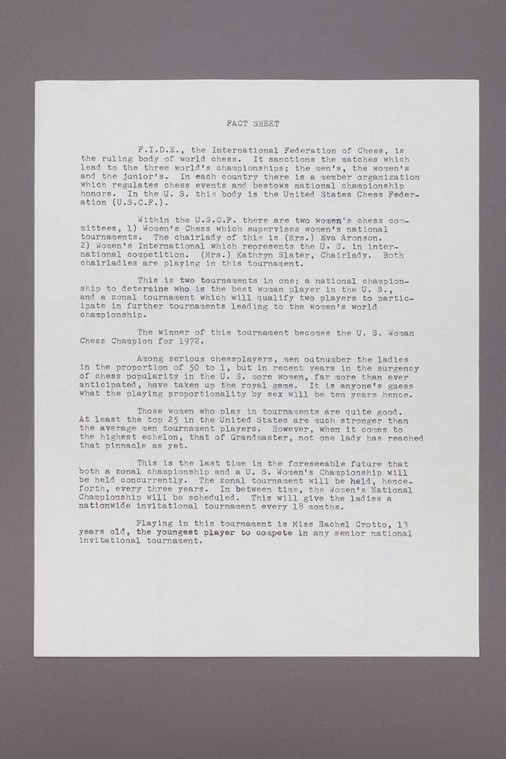

Fact Sheet from the 1974 St. Petersburg, Florida, U.S. Women’s Chess Championship and Ladies’ Zonal Tournament

1974

11 x 8 1/2 in.

Document

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

This fact sheet, prepared in advance of the 1974 U.S. Women’s Chess Championship, cites a rising interest among women in chess during that era and reflects a growing concern with attracting more American women to the game. The previous year, Gisela Gresser wrote a letter to fellow player Jacqueline Piatigorsky concerned about the level of financial and organizational support the U.S. Women’s Chess Championships then received from the United States Chess Federation (then the USCF). In it she stated, “Women’s chess is an important part of national chess life, just as much as men’s, juniors’, or armed forces chess. It is considered important in other countries and ought not to be denigrated here.”

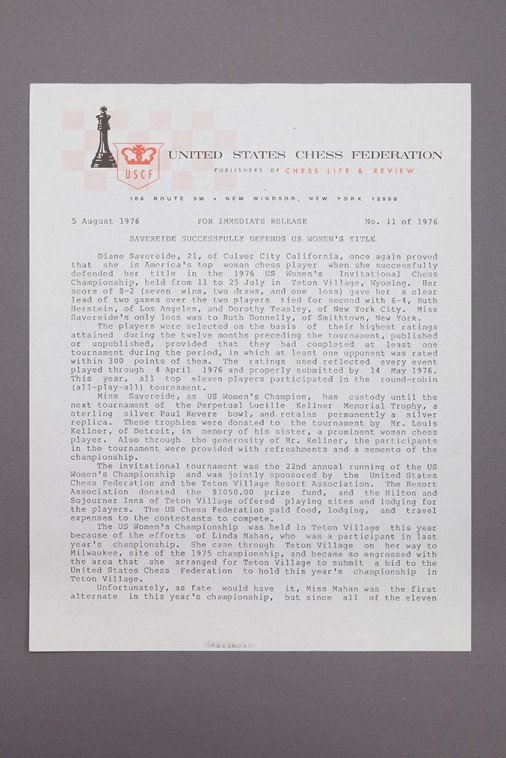

USCF Press Release from the 1976 Teton Village, Wyoming, U.S. Women’s Chess Championship:

Savereide Successfully Defends U.S. Women’s Title

August 5, 1976

11 x 8 1/2 in.

Document

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

The United States Chess Federation celebrated Diane Savereide’s second of five victories in the U.S. Women’s Chess Championship (1975, 1976, 1978, 1981, and 1984) with this press release, which was reprinted in the August, 1976, issue of Chess Life. On its reverse, the release lists the prize fund for the tournament, which included a $300 first prize. Though she would later attempt in 1984 to make a career as a professional chess player, the low prize funds that were then offered in women’s tournaments made this impossible.

Ruth Haring’s Paperweight from the 1975 Milwaukee, Wisconsin, U.S. Women’s Chess Championship

1975

3 1/2 x 2 1/2 x 3/4 in.

Paperweight

Collection of Ruth Haring

Emblazoned with a medal bearing the inscription “Diva Caissa,” celebrating the goddess of chess, tournament organizers gave this commemorative paperweight to participants in the 1975 U.S. Women’s Chess Championship. 1994 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Robert Byrne recounted the events of the tournament in his August, 12, 1975, New York Times chess column, which was titled “Good Women Are Younger and Turning Up All Over.” In it he stated, “The results of the 1975 United States women’s championship in Milwaukee show a further progress in two tendencies that have been developing for years: the ascendance of youth to the top echelons and the wider spread of talent around the country.” This marked a departure in tone from his previous article covering the competition, titled “Women’s Tournament Shows Men’s Superiority in Game.” Diane Savereide took first in the competition (then its youngest winner at age 19), while Ruth Haring tied Ruth Herstein for second. Haring and Herstein later competed in a playoff match to determine who would compete in the Interzonal Tournament, which was won by Haring.

Ruth Haring’s Commemorative Silver 1 oz Bar from the 1976 Teton Village, Wyoming, U.S. Women’s Chess Championship

1976

2 x 1 1/8 x 1/8 in.

Silver bar

Collection of Ruth Haring

This commemorative silver bar was provided to participants in the 1976 U.S. Women’s Chess Championship by Louis Kellner. Kellner, along with the United States Chess Federation supported the tournament. Pearle Mann, at the time the only woman in the United States to become a certified National Tournament Director and who was also an International Arbiter, served as the director of the tournament.

Pin from the 1991 Highland Beach, Florida, U.S. Women’s Chess Championship

1991

1 1/4 x 1 1/8 in.

Pin

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

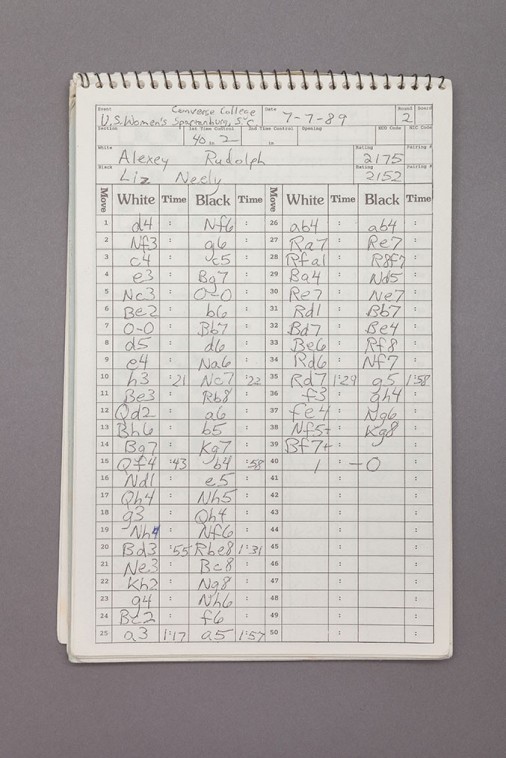

Alexey Root’s The Ultimate Chess Player’s Scorebook from the 1989 Spartanburg, South Carolina, U.S. Women’s Chess Championship

March-October 1989

8 1/2 x 5 1/2 x 1/4 in.

Scorebook

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Alexey Root

Containing games from throughout March-October, 1989, this scorebook records highlights from the career of Alexey Root. Root won the U.S. Women’s Chess Championship in 1989, a point ahead of Shernaz Kennedy, Sharon Burtman, and Vesna Dimitrijevic, who finished the tournament tied with six points. She won the trophy on view in this case (object number 12) for her victory. Rudolph has since translated her love of the game into a passion for chess and education, writing books about how teachers can integrate chess into their curriculums.

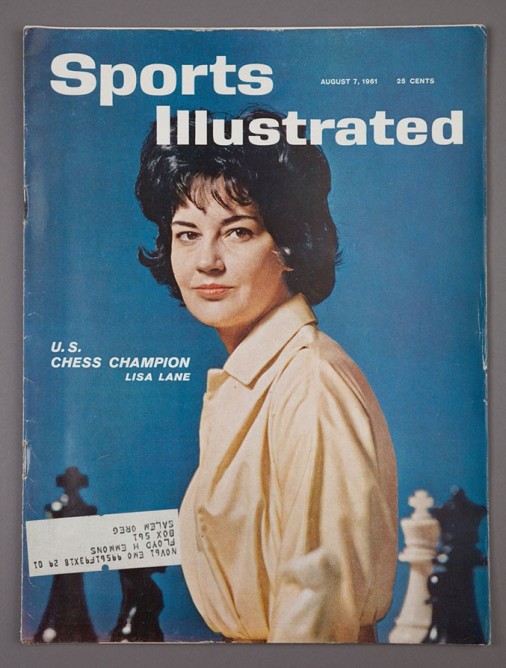

Sports Illustrated Vol. 15, No. 6

August 7, 1961

11 x 8 1/2 in.

Periodical

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

In Robert Cantwell’s August 7, 1961, Sports Illustrated article about Lisa Lane, he stated, “Where, in the history of this ancient sport (or in what other activity, for that matter), have brains and beauty been so intriguingly combined?” The quote is characteristic of the tone of the rest of his article, which meditates upon Lane’s physical appearance as much as her accomplishments and the challenges she faced in her chess career. Lane, the 1959 and 1966 U.S. Women’s Chess Champion, learned to play chess at age 19. She quickly rose to the top ranks of American women’s chess, competing in the U.S. Women’s Chess Championship only two years after taking up chess. However, Lane stopped competing in chess tournaments at age 30, only briefly returning to the world of chess in 1971 to publicly play a game against an IBM chess computer, which she won. Of the computer she stated, “It did not…appear to resent losing to a woman as do many human male players.”

Gisela Gresser’s Trophy from the 1965 New York City, New York, Lucille Kellner Memorial Tournament for the United States Chess Championships

1965

21 1/2 x 6 3/8 x 4 in.

Trophy

John G. White Chess Collection at the Cleveland Public Library

Gisela Gresser earned the 1965 Lucille Kellner Memorial Tournament Trophy, which is topped by a chess queen, for her victory in the 1965 U.S. Women’s Chess Championship. Gresser achieved this with a narrow half point victory over second place finisher Jacqueline Piatigorsky, attaining a score of 8-2 and surpassing Jacqueline’s score of 7 ½-2 ½.

Lucille Kellner, for whom the trophy is named, competed in U.S. Women’s Chess Opens (women’s competitions held alongside the U.S. Open Chess Championship), U.S. Women’s Chess Championships, and Golden Knights Postal Championships throughout the 1950s. Following her death in 1962, her brother Louis began to support women’s chess both at the national level and in her home state of Michigan in her memory. In 1965, Jacqueline Piatigorsky and Eva Aronson, two top American women players, proposed renaming the competition “The Lucille Kellner Memorial Tournament for the United States Championships” in her honor.

Chess Life & Review Vol. 34, No. 11

November 1979

11 x 8 1/4 in.

Periodical

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

Pictured on the cover of the November 1979 issue of Chess Life are three of the top American players of the mid-1970s through mid-1980s: Ruth Haring, Rachel Crotto, and 2010 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee, Diane Savereide. Published after the conclusion of the 1979 U.S. Women’s Chess Championship, this issue contains an article penned about the event by the competition’s winner, Rachel Crotto. In 1978, Crotto had shared the title with Savereide. In her piece, she analyzed two games from the tournament—the first against Ruth Haring and another against Diana Lanni. Crotto competed in her first U.S. Women’s Chess Championship in 1972 at the then-record age of 13. Composer John Cage, noting her talent, paid for her to take lessons with Bobby Fischer’s mentor John Collins. In his famous book My Seven Chess Prodigies, Collins described her as one of “the youngsters for whom he [had] high hopes” and relayed her ambition to become “one of the strongest players in the country, not just one of the strongest female players.”

Alexey Root’s Trophy from the 1989 Spartanburg, South Carolina, United States Women’s Invitational Tournament Championship

1989

17 x 6 1/2 x 4 in.

Trophy

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Alexey Root

Women’s World Chess Championships

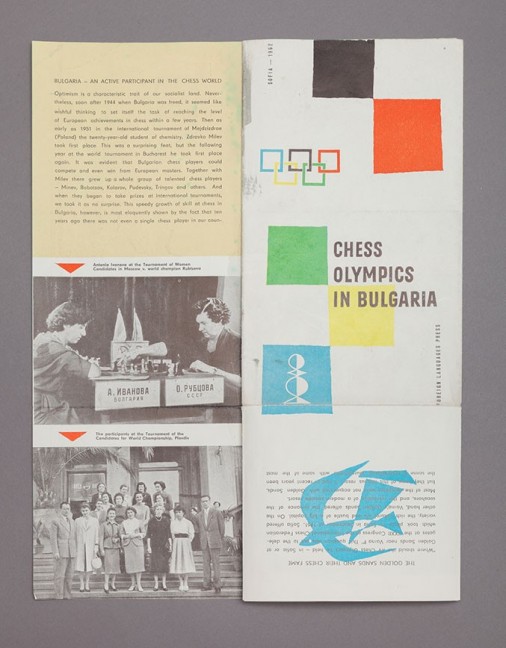

Program from the 1962 Varna, Bulgaria, Chess Olympiad

1962

11 13/16 x 18 3/8 in.

Program

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

M. Anfinger © Изда́тельство

Olga Rubtsova Postcard

1982

5 3/4 x 4 1/8 in.

Postcard

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

M. Anfinger © Изда́тельство

Lyudmila Rudenko Postcard

1982

5 3/4 x 4 1/8 in.

Postcard

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Born in Lubny, Ukraine, Lyudmila Rudenko started playing chess at age ten, but did not seriously study the game until a move to Moscow in 1925. Her first major competition was the 1927 U.S.S.R. Women’s Chess Championship, in which she placed fifth. The following year, she won the Moscow Women’s Championship ahead of reigning U.S.S.R. Women’s Champion, Olga Rubtsova. In 1950, Rudenko won the first Women’s Chess Championship held following World War II, becoming only the second Women’s World Chess Champion after Vera Menchik. Two years later, Rudenko won the U.S.S.R. Women’s Championship. In 1950, she earned the title of international master and in 1976 became a woman grandmaster.

Gisela Gresser

Gisela Gresser’s Photo Album from the 1961 Vrnjačka Banja, Yugoslavia (present-day Serbia), Women’s Candidates Tournament

c 1961

8 x 12 x 1 1/2 in.

Photo album

John G. White Chess Collection at the Cleveland Public Library

Gisela Gresser may have assembled this photo album when she competed in the 1961 Women’s Candidates Tournament in Vrnjačka Banja, Yugoslavia (present-day Serbia). It contains images of Nona Gaprindashvili, who won the tournament, thereby earning the chance to challenge reigning Women’s World Chess Champion Elizaveta Bykova in a match in Moscow, Russia, the following year.

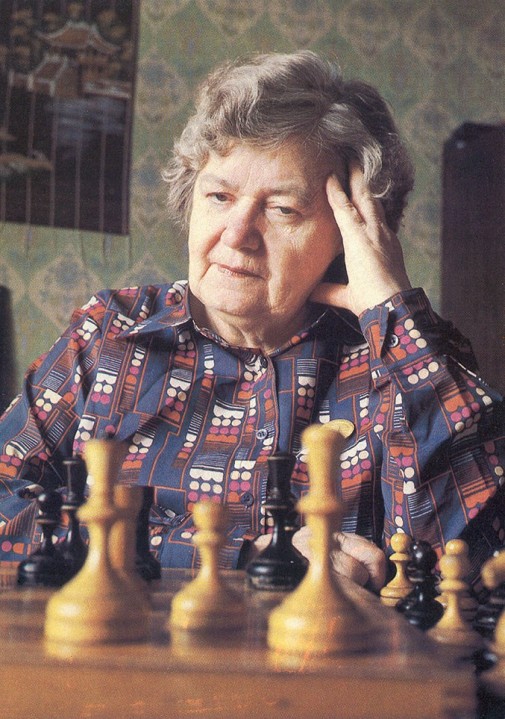

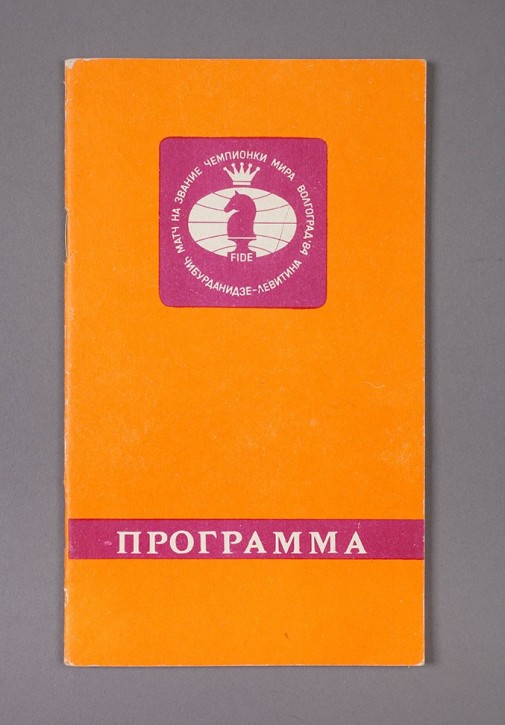

1984 Tbilisi, Georgia, Women’s World Championship Program

1984

7 5/8 x 4 1/2 in.

Program

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

Produced for the 1984 Women’s World Chess Championship, this program includes a list of all of the previous competitions’ winners, along with a smiling image of Maya Chiburdanidze. In this year, Chiburdanidze defended her title against challenger Irina Levitina. Their match was closely fought, but Levitina blundered in the ninth game, allowing Chiburdanidze to win. Chiburdanidze then earned three and a half points in their final games, earning her the title again.

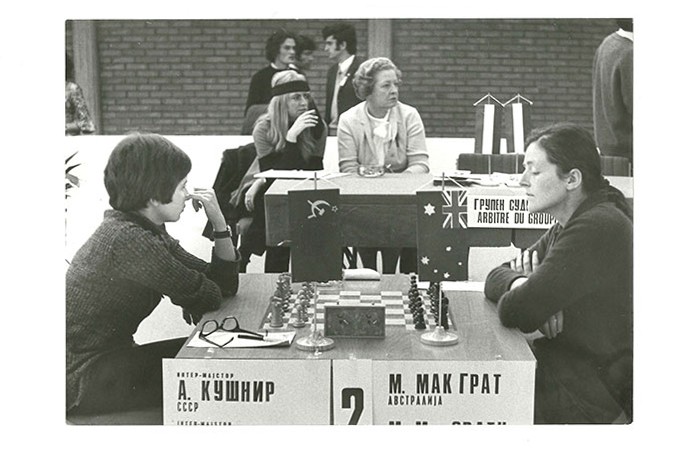

Photographer unknown

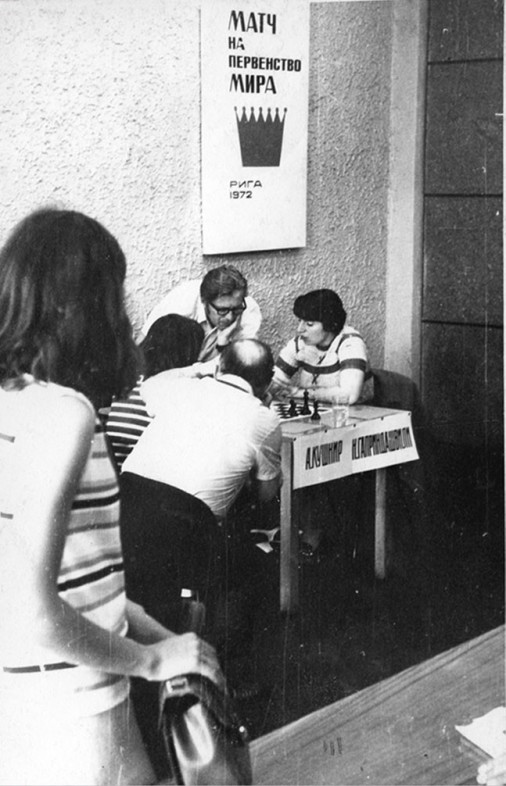

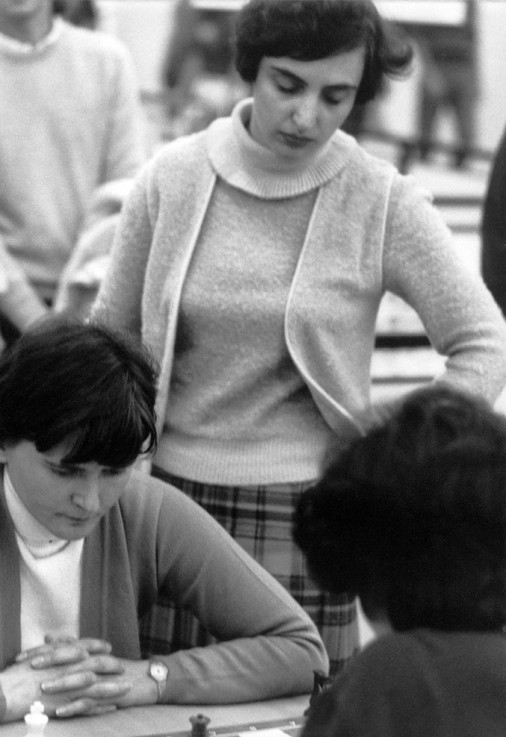

WGM Alla Kushnir (U.S.S.R./Israel) vs. Marion McGrath (Australia) at the 1967 Subotica, Serbia, Candidates Tournament

1967

5 x 7 1/8 in.

Photograph

Collection of Richard Benjamin

Nona Gaprindashvili’s closest competitor in the 1960s was Soviet (and later Israeli) Woman Grandmaster Alla Kushnir. Kushnir contested the Women’s World Chess Championship with Gaprindashvili three times, coming closest to winning in the 1972 Women’s World Chess Championship, when she ended the match only a point behind Gaprindashvili. Kushnir immigrated to Israel in 1973, and as a condition of the move, she agreed not to take part in the following Women’s World Chess Championship cycle. While representing the Soviet Union and later, Israel, in the Women’s Chess Olympiads, Kushnir would win three team and three individual gold medals.

Photographer unknown

Nona Gaprindashvili (U.S.S.R./Georgia) and Alla Kushnir (U.S.S.R./Israel) at the 1972 Riga, Latvia, Women’s World Chess Championship

1972

5 1/2 x 3 5/8 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Five-time winner of the Women’s World Chess Championship, Nona Gaprindashvili held the title from 1962-1978, when she lost it to Maya Chiburdanidze. Gaprindashvili’s accomplishments were instrumental in proving that women could compete with men on the international stage. In 1978 she was the first woman to be awarded the title of grandmaster by the World Chess Federation (Federation Internationale des Échecs or FIDE). She earned this distinction for her impressive performance in the 1977 Lone Pine International Tournament, in which she shared first place.

Photographer unknown

Olga Nikolayevna Rubtsova (U.S.S.R.) with Daughter

c 1950s

5 1/4 x 4 1/8 in.

Photograph

Collection of Richard Benjamin

Born in Moscow, Olga Rubtsova learned to play chess at age fifteen. Only three years later, she won her first U.S.S.R. Women’s Chess Championship, a feat she would repeat in 1931, 1937, and 1949. In 1950, Rubtsova earned the titles of both international master and woman international master. She reigned as Women’s World Chess Champion from 1956-1958 and played first board for the Soviet team that won the first Women’s Chess Olympiad in 1957.

Photographer unknown

Nona Gaprindashvili (U.S.S.R./Georgia) at Award Ceremony

c 1970s

5 x 5 in.

Photograph

Collection of Richard Benjamin

Photographer unknown

Competitors Posing for Photo in Tbilisi during the 1961 Tbilisi/Batumi, Georgia, Women’s Tournament

April 24 – May 15, 1961

9 x 5 1/2 in.

Photograph

Collection of Michael Utt

Pictured at the center is Nona Gaprindashvili, who rose to stardom in 1961 as she earned the chance to compete for the Women’s World Chess Championship against Elizaveta Bykova. She would go on to use her sharp, attacking style to defeat Bykova 9-2 in the 1962 Women’s World Chess Championship.

Chess Life & Review Vol. 34, No. 1

January 1979

11 x 8 1/4 in.

Periodical

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

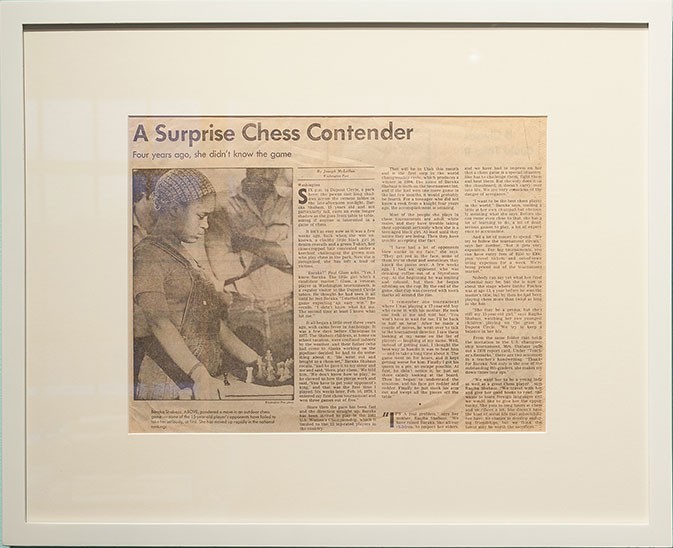

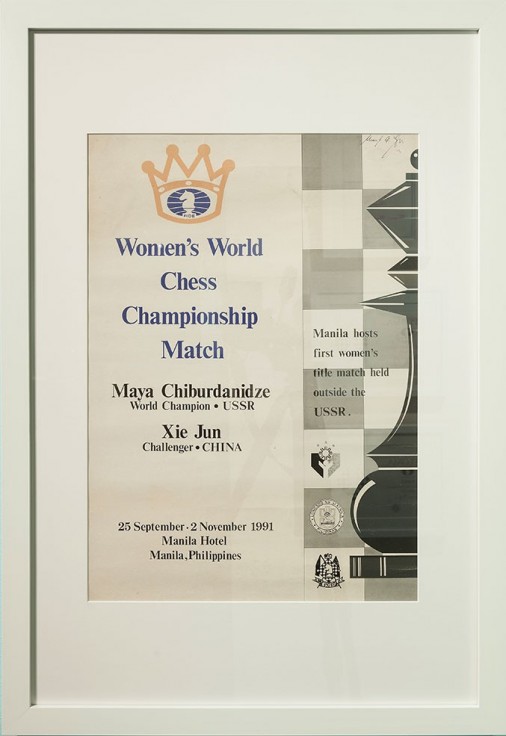

Maya Chiburdanidze’s introspective, exceptional play earned her a place at the top of women’s chess from a young age. In 1977, she won the U.S.S.R. Women’s Chess Championship. The following year she defeated Nona Gaprindashvili in the Women’s World Chess Championship, becoming the new World Chess Champion at age seventeen. Chiburdanidze would defend her title four times, finally losing it in 1991 to Xie Jun. A pioneer in women’s chess, in 1984 Chiburdanidze become only the second woman to earn the title of grandmaster.

Women’s Chess Olympiads

Pins from the 1990 Novi Sad, Yugoslavia (present-day Serbia), Chess Olympiad

1990

1 1/2 x 5/8 in.

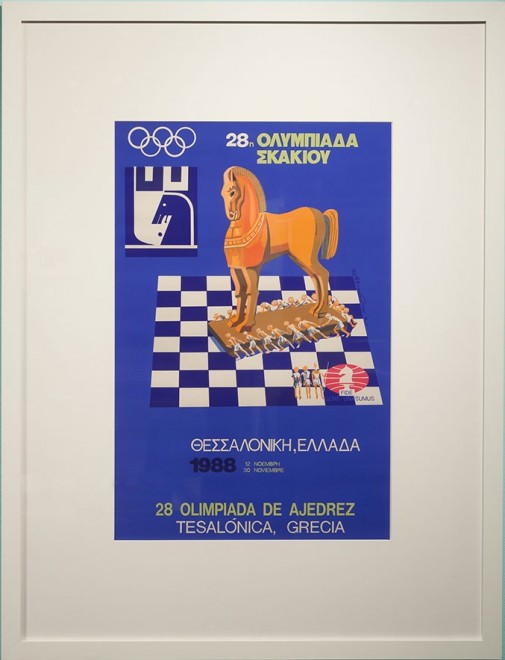

Pin from the 1988 Thessaloniki, Greece, Chess Olympiad

1988

5/8 x 7/16 in.

Pins

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Displayed here are several commemorative pins from the 1988 Thessaloniki and the 1990 Novi Sad Olympiads. Each bears the logo for its respective competition—for Thesssaloniki, a pair of knights, and for Novi Sad, a rook topped by a dove. The Novi Sad pins are created in a similar design to the medals earned by players, one of which is on view in this case.

Susan Polgar’s Gold Medal from the 1990 Novi Sad, Yugoslavia (present-day Serbia), Chess Olympiad

1990

4 x 2 3/4 x 1/8 in.

Medal

Collection of Susan Polgar

In 1990, the Hungarian Olympiad team, comprised of Susan Polgar, Judit Polgar, Sofia Polgar, and Ildiko Madl, took team gold in a closely fought competition with their rivals on the Soviet team. Hungary trailed the Soviet team going into the second to last round, but came back, ending tied with the Soviets after the last round. Hungary won on a tiebreak, and Susan earned this gold medal for her performance on Board One.

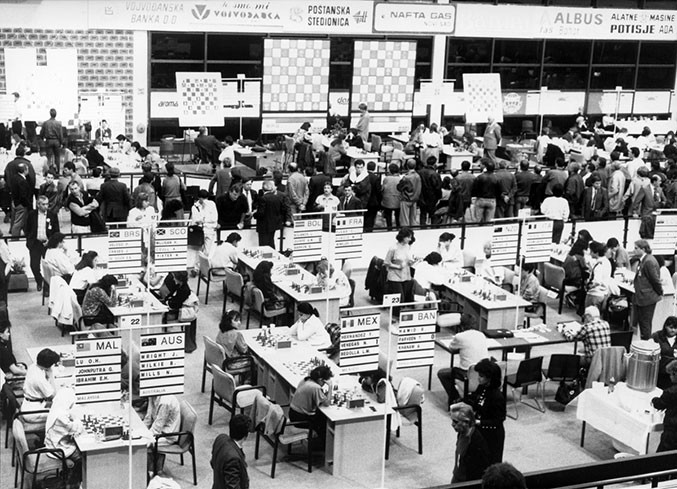

Bill Hook

Playing Hall with Female Competitors at the 1990 Novi Sad, Yugoslavia (present-day Serbia), Chess Olympiad

1990

5 x 6 15/16 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Center

Bill Hook

Susan Polgar (Hungary) at the 1990 Novi Sad, Yugoslavia (present-day Serbia), Chess Olympiad

1990

5 3/4 x 4 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Center

Susan, Judit, and Sofia Polgar represented Hungary in the Novi Sad, Yugoslavia (present-day Serbia), Women’s Chess Olympiad. They triumphed over the formerly-dominant Soviet team, not only winning the team gold medal, but also each winning individual gold medals. Susan won the gold medal for her performance on Board One, which is also on display in this case.

Bill Hook

Susan Polgar (Hungary) at the 1994 Moscow, Russia, Chess Olympiad

1994

6 x 4 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Center

Susan Polgar is pictured here at the 1994 Women’s Chess Olympiad in Moscow, Russia. Polgar overcame many obstacles during her career. One of her earliest ones was Hungary’s refusal to allow her to play in their national chess championship due to her gender. In her book Breaking Through: How the Polgar Sisters Changed the Game of Chess (2005), she wrote, “I am proud that, because of my success, I paved the road for the future, as at the Following FIDE congress (in 1986) the name of the event [the Men’s World Chess Championship] was changed to the ‘World Chess Championship’. They eliminated the word “men’s’. Today, for girls around the world, the doors are open at chess tournaments.” Though initially reluctant to play in women’s tournaments, Polgar ultimately played in many, like this Olympiad, over the course of her career.

Bill Hook

Xie Jun (China) at the 1994 Moscow, Russia, Chess Olympiad

1994

6 x 4 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Center

Bill Hook

Nana Ioseliani (Georgia) at the 1994 Moscow, Russia, Chess Olympiad

1994

6 x 4 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Center

Bill Hook

Xie Jun (China) at the 1992 Manila, Philippines, Chess Olympiad

1992

6 x 4 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Center

Bill Hook

Judit Polgar (Hungary) at the 1994 Moscow, Russia, Chess Olympiad

1994

6 x 4 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Center

1990 was the last year in which Susan, Judit, and Sofia Polgar would compete together on the same Olympiad team. In the following Olympiads, through her last one in 2014, Judit would represent Hungary in the open section. She earned team silver medals in 2002 and 2014 and an individual bronze medal for her performance on Board Two in 2002.

Bill Hook

Sofia Polgar (Hungary) at the 1994 Moscow, Russia, Chess Olympiad

1994

6 x 4 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Center

The Hungarian women’s team, minus Judit Polgar, was not able able to repeat their gold medal winning performances of 1988 and 1990, at Moscow 1994, but it was no fault of Sofia Polgar. Playing second board she scored an undefeated 12 ½ from 14, good for individual gold on board two and the best performance of the entire Olympiad.

Bill Hook

Maya Chiburdanidze (Georgia) at the 1994 Moscow, Russia, Chess Olympiad

1994

6 x 4 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Center

Following the fall of the Soviet Union, Maya Chiburdanidze represented the newly-independent nation of Georgia in the Women’s Chess Olympiads. In 1992, 1994, 1996, and 2008, her team would win team gold, and she also won two individual gold medals while representing Georgia. Combined with her earlier wins for the Soviet Union, Chiburdanidze has won an impressive nine team gold medals and four individual gold medals over the course of her career.

Susan Polgar’s Individual Gold Medal from the 2004 Calvià, Majorca, Spain, Chess Olympiad

2004

Medal: 2 11/16 in. dia.

Box: 5 x 5 x 1 1/2 in.

Medal, velvet box

Collection of Susan Polgar

Susan Polgar’s Team Silver Medal from the 2004 Calvià, Majorca, Spain, Chess Olympiad

2004

Medal: 2 11/16 in. dia.

Box: 3 3/4 x 4 x 1 1/8 in.

Medal, velvet box

Collection of Susan Polgar

Displayed here are Susan Polgar’s Team Silver Medal from the 2004 Women’s Chess Olympiad, along with the Individual Gold Medal she won in the same tournament. Polgar came out of retirement to compete, and she was joined by a team of young stars of American chess: Irina Krush, Anna Zatonskih, and Jennifer Shahade. Rusudan Goletiani also trained with the team, which Susan joined (changing chess federations from Hungary) with the aim of promoting chess in the United States. With the help of the Kasparov Chess Foundation, Team Captains Paul Truong and Susan Polgar developed a training program for the Olympiad team, which resulted in the first team medal for the United States in the Women’s Chess Olympiad.

Susan Polgar’s Signed Dream Team Calendar from the 2004 Calvià, Majorca, Spain, Chess Olympiad

2004

8 1/2 x 11 x 1/16 in.

Calendar

Collection of Susan Polgar

Each of the competitors from the 2004 U.S. Women’s Chess Olympiad team signed the cover of this calendar. Anna Zatonskih, pictured at left, played on Board Three. Rusudan Goletiani, second from left, trained with the team but did not play in the Olympiad. However, she won the 2005 U.S. Women’s Chess Championship the following year. At the center is Susan Polgar, who came out of retirement to join the team and played on Board One. To her right is Jennifer Shahade, who was the team’s reserve player and was the winner of the 2002 and 2004 U.S. Women’s Chess Championships. To her right is Irina Krush, who is a seven-time winner of the U.S. Women’s Chess Championships (2007, 2010, 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015), and who played on Board Two in the tournament.

The Polgar Sisters

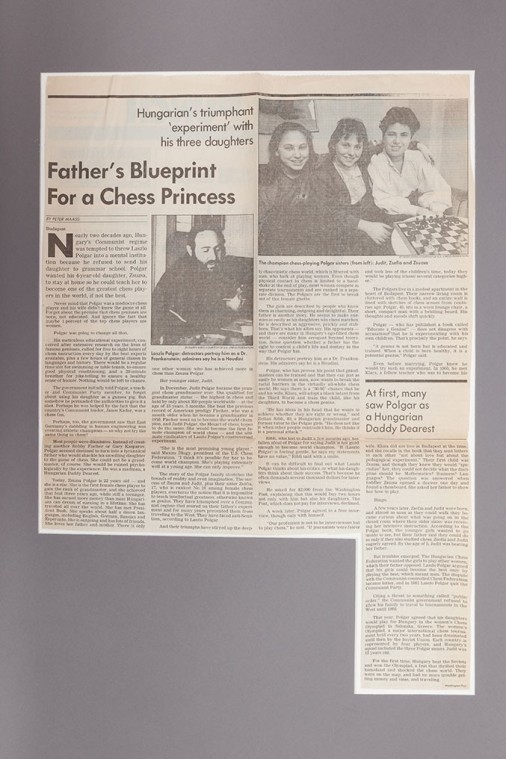

Peter Maass

“Father’s Blueprint For a Chess Princess” The San Francisco Chronicle

March 22, 1992

18 3/4 x 13 in.

Newspaper Clipping

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

In this article, journalist Peter Maass celebrates Laszlo Polgar’s “experiment” in raising his daughters to become chess prodigies. Maass details how Polgar was initially discouraged from keeping Susan out of school so that she could concentrate on developing her chess talent, but ultimately received support. He studied the lives of famous geniuses to formulate his training for his daughters. It also describes how Susan’s successes at an early age inspired her younger sisters to take up the game. At the time the article was written, Susan had become the first woman to earn the title of grandmaster, and her younger sister Judit had attained the grandmaster title at age 15 years and four months, beating the record previously set by Bobby Fischer in 1958.

Susan Polgar’s 2013 FIDE Furman Symeon Award

2013

9 3/4 x 1 1/2 x 1 1/2 in.

Trophy

Collection of Susan Polgar

In 2013, Susan Polgar earned the Furman Symeon Award in recognition of her endeavors in the field of chess training. Polgar was the first woman to win the award. Her work as the coach at Texas Tech and Webster University, as well as her efforts to promote chess among young women earned her the award.

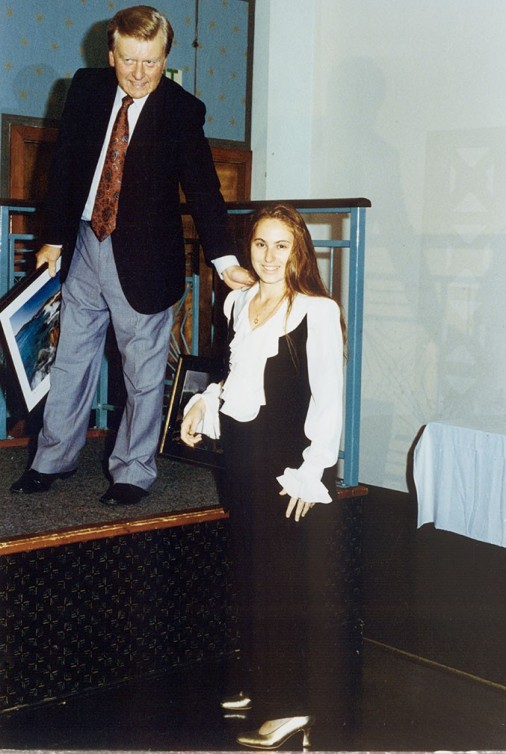

Lesley Collett

Judit Polgar (Hungary) Receiving Her Award for Taking First at the 1995 Isle of Lewis, Scotland, Chess Tournament

1995

7 x 5 in.

Photograph

In 1995, the Lewis Chess Club organized a chess tournament to celebrate the British Museum’s three-month loan of the Lewis Chess Set to the newly opened Isles Museum. The 12th-century walrus ivory chess pieces were excavated on the Isle of Lewis in Scotland in 1831. Polgar took first in the tournament, overcoming three other opponents: Nigel Short, Simon Agdestein, and Paul Motwani.

Photographer unknown

Young Susan Polgar Playing Blitz

1975

4 x 5 15/16 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Photographer unknown

Winners of the 1990 Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, World Youth Championship

1990

5 x 7 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

This photo captures a historic moment in the history of the World Youth Chess Festival—it was taken in 1990, the year that Judit Polgar became the first girl to win the open section of the competition. Pictured in the photo, from left to right are: Evelyn Moncayo Romero (Ecuador, winner of the Girls Under 10 competition), Judit Polgar (Hungary, winner of the “Boy’s” under 14), Nawrose Nur (United States, winner of the Boys Under 10 competition), Corina Peptan (Romania, winner of Girls Under 12 competition), Diana Darchia (Russia, winner of the Girls Under 14 competition), Boris Avrukh (Israel, winner of the Boys Under 12 competion), Tournament Director Carol Jarecki, and Tournament Organizer Donald Schultz.

Pin from the 1990 Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, World Youth Championship

1990

1 1/16 x 1 1/16 in.

Pin

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Photographer unknown

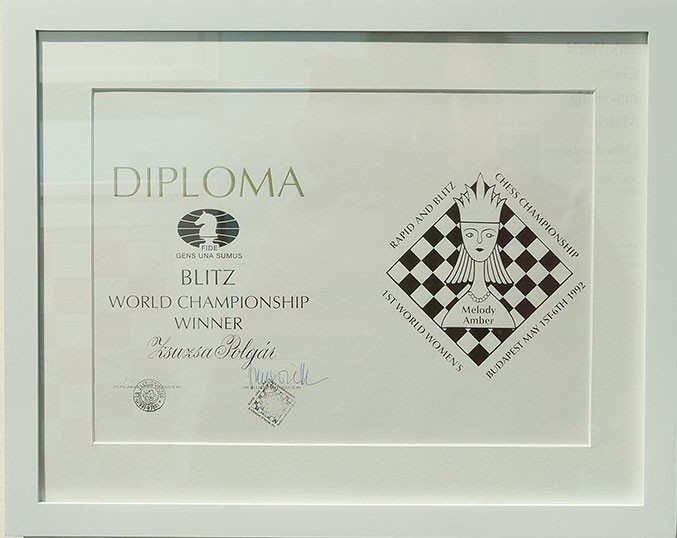

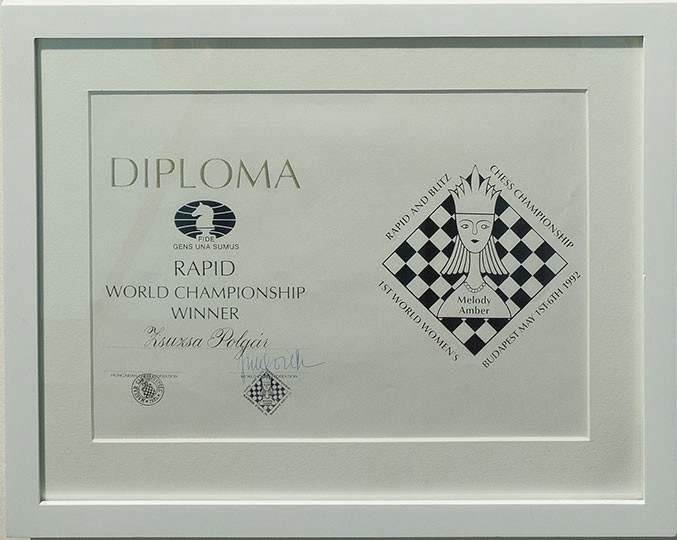

Judit Polgar (Hungary), Susan Polgar (Hungary), and Alisa Galliamova (Russia) during Award Ceremony at the 1992 Budapest, Hungary, Women’s World Blitz Championship

1992

3 1/2 x 5 1/8 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Susan Polgar receives her award for her victory in the 1992 Women’s World Blitz Championship in this photo. In the competition, each player was given five minutes to make their moves. Pictured beside her are her sister, Judit Polgar, who took second place in the tournament, and Russian player Alisa Galliamova who finished third. Polgar took first in the 1992 Women’s World Rapid Championship, which was held at the same venue. In that competition, she went undefeated, and placed ahead of her other sister, Sofia, who took second, as well as former Women’s World Chess Champion Maya Chiburdanidze in third, and Judit in fourth place.

Photographer unknown

Bobby Fischer Playing Chess with Susan Polgar

c 1992-1993 4 x 6 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Legendary American player Bobby Fischer plays Fischer Random Chess, a chess variant he created in which the starting positions of the pieces are randomized, against Susan Polgar in this photograph. Fischer stayed with the Polgar family after leaving the United States. During that time, Susan assisted Bobby in developing the rules of Fischer Random Chess. She is the only known person to be pictured playing the chess variant with him.

Bill Hook

Lajos Portisch (Hungary) and Judit Polgar (Hungary) at the 1994 Moscow, Russia, Chess Olympiad

1994

4 x 6 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Center

Photographer unknown

Susan Polgar (Hungary) Competing at the 1990 Novi Sad, Yugoslavia (present-day Serbia), Chess Olympiad

1990

2 9/16 x 3 3/4 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Susan Polgar gazes intently at her competitor in this photograph from the 1990 Novi Sad, Yugoslavia, Chess Olympiad. Polgar won a gold medal in this Olympiad for her performance on Board One. More artifacts related to this event, including her medal, are located in this gallery.

Inside Chess Vol. 2, Issue 7

April 17, 1989

10 13/16 x 8 5/16 in.

Periodical

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

Sofia Polgar holds a trophy, a beaming smile on her face, in the photo emblazoned on the cover of this issue of Inside Chess. It celebrates her win at the “Magistrale di Roma,” in which she achieved a performance rating for the tournament of over 2900, one of the best ever recorded. She overcame strong opposition, including Grandmasters Alexander Chernin, Semon Palatnik, Yuri Razuvaev, and Mihai Suba, to win the open tournament. The tournament was the highlight of her career and at the time one of the best results by any player.

Chess Life Vol. 47, No. 11

November 1992

10 3/4 x 8 1/4 in.

Periodical

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Charles Ward

Judit, Sofia, and Susan Polgar pose on the cover of this colorful issue of Chess Life. Inside, the magazine details the events of the United States Chessathon, a charity event in which the three sisters appeared. Judit took second in the 1992 U.S. Chess International (Samuel Reshevsky Memorial), behind Grandmaster Julio Granda Zuniga.

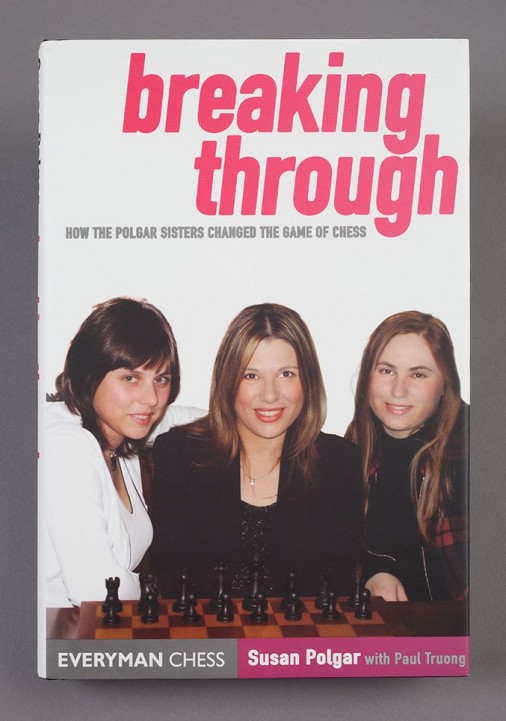

Susan Polgar with Paul Truong

Breaking Through: How the Polgar Sisters Changed the Game of Chess

2005

9 1/4 x 6 x 1 in.

Book

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

In Breaking Through: How the Polgar Sisters Changed the Game of Chess, Susan Polgar details the lives and chess careers of herself and her famous sisters, Sofia and Judit. The book provides analysis of games from many of the most important competitions of their careers. It also describes the challenges that they faced in their groundbreaking careers. Polgar’s husband, Paul Truong, also provides an account of the 2004 Women’s Chess Olympiad, when Susan was part of the first American women’s team to win a team medal at the competition.

Women’s World Chess Championships

Alexandra Kosteniuk’s Medal from the 2008 Nalchik, Russia, Women’s World Chess Championship

2008

Medal: 2 11/16 in. dia. Box: 3 6/16 x 4 9/16 x 5/8 in.

Medal, plastic case

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

In the final round of the 2008 Women’s World Chess Championship, Alexandra Kosteniuk triumphed over 14-year-old Hou Yifan to win the title. Kosteniuk had previously reached the finals in the 2001 Women’s World Chess Championship tournament, losing to Zhu Chen. Kosteniuk has used her position as Women’s World Chess Champion to promote the game of chess worldwide.

Photographer unknown

Susan Polgar (Hungary)

Receiving Her Award at the 1996 Jaén, Spain, Women’s World Chess Championship

1996

5 x 7 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Susan Polgar celebrates her victory in the 1996 Women’s World Chess Championship, as World Chess Federation (FIDE, or Federation Internationale des Échecs) President Kirsan Ilyumzhinov applauds and her opponent, Xie Jun, stands nearby. Polgar had begun playing in the Women’s World Chess Championship cycle in 1992, and lost the 1993 Candidates Tournament to Nana Ioseliani in a drawing of the lots following a tied match. Undeterred, she competed in the following cycle, triumphing not only over former Women’s World Chess Champion Maya Chiburdanidze, but also Xie Jun. The dress and scarf that Polgar is wearing in this photo are part of the collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame.

Lesley Collett

Xie Jun (China) at the 1997 Groningen, The Netherlands, FIDE Candidates Tournament

December 14, 1997

4 x 5 7/8 in.

Postcard

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Raquel Browne

In 1996, reigning Women’s World Chess Champion Xie Jun lost her title to Susan Polgar. Following the World Chess Federation’s (Federation Internationale des Échecs or FIDE) controversial declaration that Polgar had forfeited the championship title, FIDE organized a championship match between Xie Jun and Alisa Galliamova. Xie Jun won the match, becoming only the second woman since Elizaveta Bykova to regain the championship title after losing it.

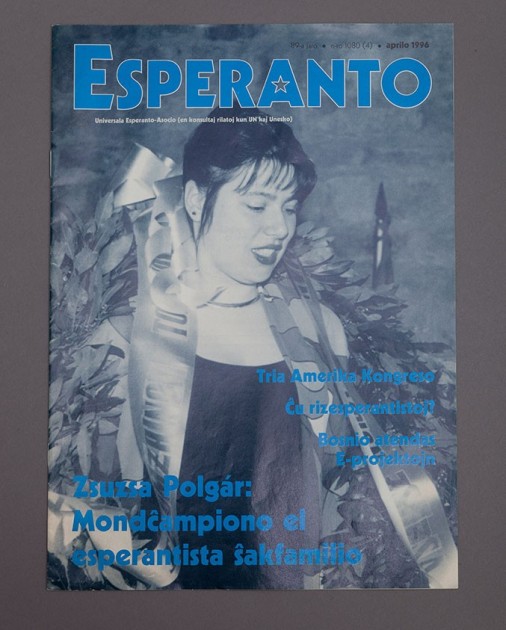

Esperanto Vol. 89, No. 1080 (4)

April 1996

10 1/2 x 7 1/2 in.

Periodical

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Susan Polgar’s Trophy from the 1996 Jaen, Spain, Women’s World Chess Championship

1996

11 1/4 x 9 1/2 x 9 in.

Trophy

Collection of Susan Polgar

Susan Polgar earned this trophy for her victory in the 1996 Women’s World Chess Championship. Made of silver, it is modeled after an olive tree—a tribute to the olive oil for which Jaen, Spain, the city in which the 1996 Women’s World Chess Championship was held, is famous. The wood from which the trophy’s base is made also comes from an olive tree.

64, No. 10

2008

10 1/4 x 7 in.

Periodical

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Women’s Chess Olympiads

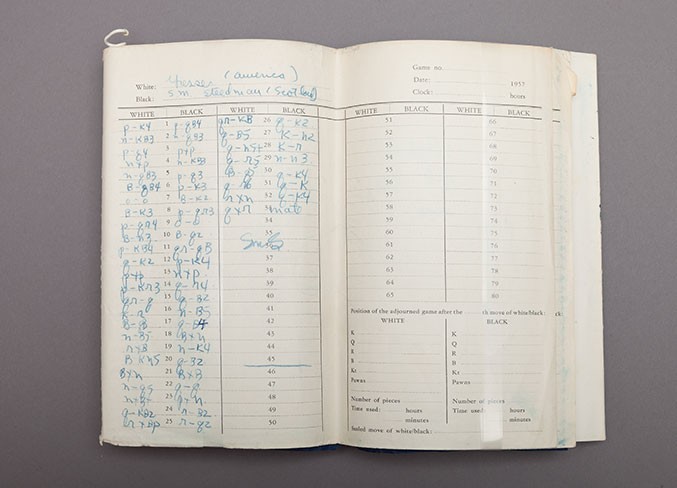

Gisela Gresser’s Scorebook from the 1957 Emmen, The Netherlands, Women’s Chess Olympiad

1957

7 3/4 x 5 x 3/8 in.

Scorebook

John G. White Chess Collection at the Cleveland Public Library

Gisela Gresser recorded her games in this scorebook given to competitors. In a 1957 British Chess Magazine article, a fellow competitor, Beth Cassidy of Ireland, detailed the efforts of some of the players to gain a psychological edge over their opponents. She concluded by saying, “And where do you leave Mrs. Gresser, of the United States, who, with a delightful contempt for her opponent, caught up with her correspondence in between moves?”

Gisela Gresser’s Bronze Medal from the 1957 Emmen, The Netherlands, Women’s Chess Olympiad

1957

Medal: 1 9/16 in. dia. Box: 2 7/8 x 2 7/8 x 3/4 in.

Medal, leather box

John G. White Chess Collection at the Cleveland Public Library

Like her teammate Jacqueline Piatigorsky, Gisela Gresser won an individual bronze medal at the first Women’s Chess Olympiad. Through their efforts, the United States finished at the top to the Group B finals. The overall competition was won by the Soviet Team, which included reigning Women’s World Chess Champion Olga Rubtsova at Board One.

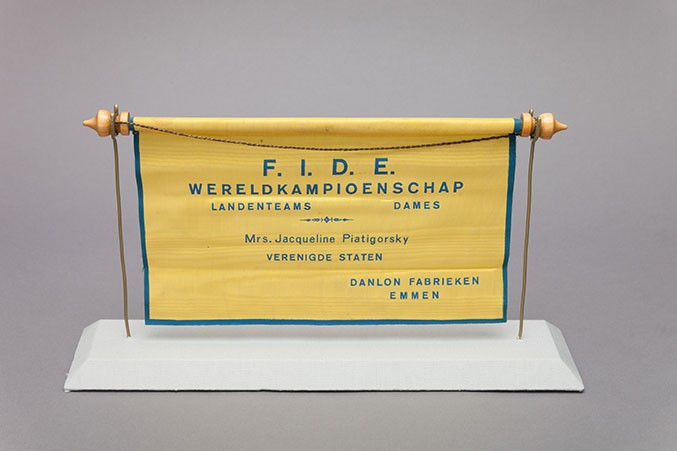

Jacqueline Piatigorsky’s Flag from the 1957 Emmen, The Netherlands, Women’s Chess Olympiad

1957

5 1/4 x 11 in.

Fabric and wood

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

This flag, which dates from the first Women’s Chess Olympiad, identifies Jacqueline Piatigorsky, who along with Gisela Gresser, represented the United States in the competition. The first Women’s Chess Olympiad was held in Emmen, The Netherlands, not far from the German border. Unlike Women’s Olympiads today, which are played on four boards with a reserve player, in Emmen each team had only two players and no reserves, so both players played every match.

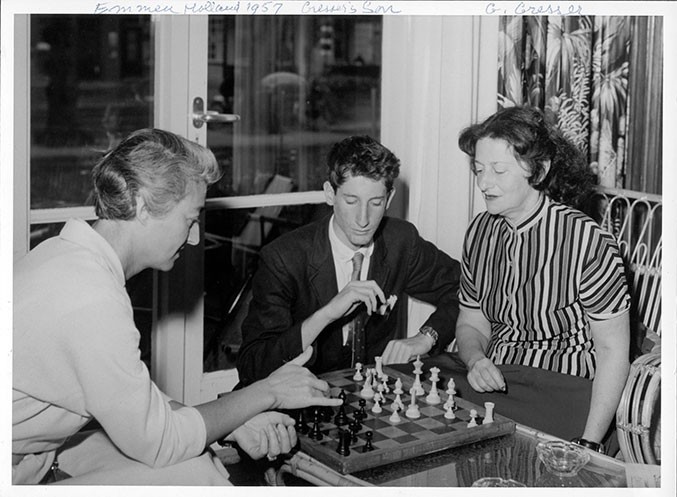

Wilko A G.M. Bergmans

Jacqueline Piatigorsky, Gisela Gresser, and Julian Gresser Analyzing a Chess Position while in Emmen, The Netherlands, during the 1957 Women’s Chess Olympiad

1957

5 1/8 x 7 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

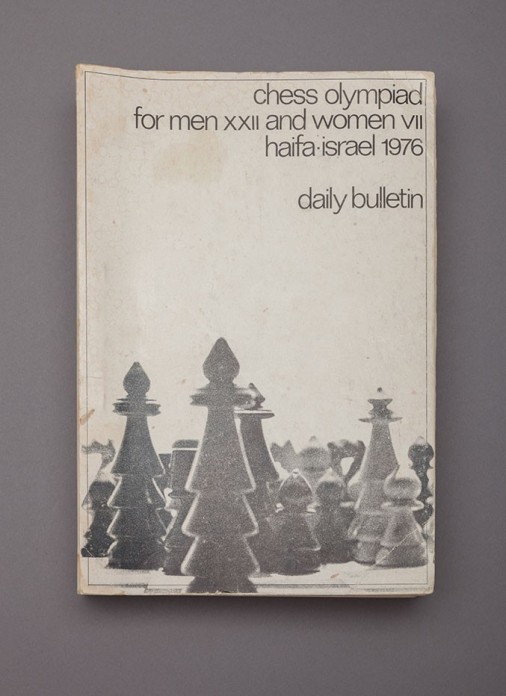

Ruth Haring’s Tournament Bulletins from the 1976 Haifa, Israel, Chess Olympiad

1976

9 1/2 x 6 1/2 x 1 1/2 in.

Bulletins

Collection of Ruth Haring

1976 marked the first year in which the Men’s and Women’s Chess Olympiads were held concurrently. Many middle-eastern and Soviet bloc nations declined to participate for political reasons, organizing their own “anti-Olympiad” in Tripoli, Libya. Since the Soviet women’s team had dominated the competition in other years, this opened up opportunity for other countries, and the Israeli team led by Alla Kushnir took first.

Ruth Haring’s Bronze Medal from the 1976 Haifa, Israel, Chess Olympiad

1976

2 5/16 in. dia.

Medal

Collection of Ruth Haring

The American team, comprised of Diane Savereide, Ruth Herstein, and Ruth Haring took fourth place in the 1976 Women’s Chess Olympiad. Haring won this Bronze Medal for her performance on the reserve board. Before the tournament, United States Chess Federation Executive Director and 1995 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Ed Edmondson “expressed hope that their participation would help lure more women into the game, which has been dominated by men.”

Bill Hook

U.S.S.R. Team at the 1988 Thessaloniki, Greece, Chess Olympiad

1988

4 x 6 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Center

Bill Hook

Judit Polgar (Hungary) Playing against Diane Savereide (U.S.A.) at the 1988 Thessaloniki, Greece, Olympiad

1988

4 x 6 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Center

1988 was the first year in which Judit Polgar represented Hungary at the World Chess Olympiad. Here she competes with Diane Savereide, a five-time U.S. Women’s Chess Champion (1975, 1976, 1978, 1981, and 1984). Polgar triumphed in the game, winning a point for Hungary.

Bill Hook

Pia Cramling (Sweden) Competing at the 1984 Thessaloniki, Greece, Chess Olympiad

1984

3 7/16 x 5 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Center

Pia Cramling won the individual gold medal on Board One in the 1984 Thessaloniki, Greece, Women’s Chess Olympiad. Like her contemporary, Judit Polgar, Cramling would later begin to represent her country in the open section of the Chess Olympiads (1990, 1992, 1996, and 2000).

Bill Hook

Jana Maskova (Czechoslovakia) vs. Judit Polgar (Hungary) at the 1988 Thessaloniki, Greece, Chess Olympiad

1988

4 x 6 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Center

Judit Polgar, pictured here, was the highest scoring member of her team. Following the defection of Elena Akhmilovskaya Donaldson after the tenth round, the Hungarian team triumphed, winning the tournament by half a point. Akhmilovskaya would later become a three-time U.S. Women’s Chess Champion (1990, 1993, and 1994).

Bill Hook

Irina Levitina (U.S.S.R.) watches her teammate Lidia Semenova at the 1984 Thessaloniki, Greece, Chess Olympiad

1984

5 x 3 3/8 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Center

In this photograph, Irina Levitina observes her teammate Lidia Semenova. Semenova went on to earn the best performance rating in the tournament, as well as the Individual Gold Medal as the best reserve player. Levitina later immigrated to the United States, where she would win three U.S. Women’s Chess Championships (1991, 1992, and 1993).

Bill Hook

Diane Savereide (U.S.A.) vs. Maya Chiburdanidze (U.S.S.R.) at the 1984 Thessaloniki, Greece, Chess Olympiad

1984

3 1/2 x 4 15/16 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Center

Writers

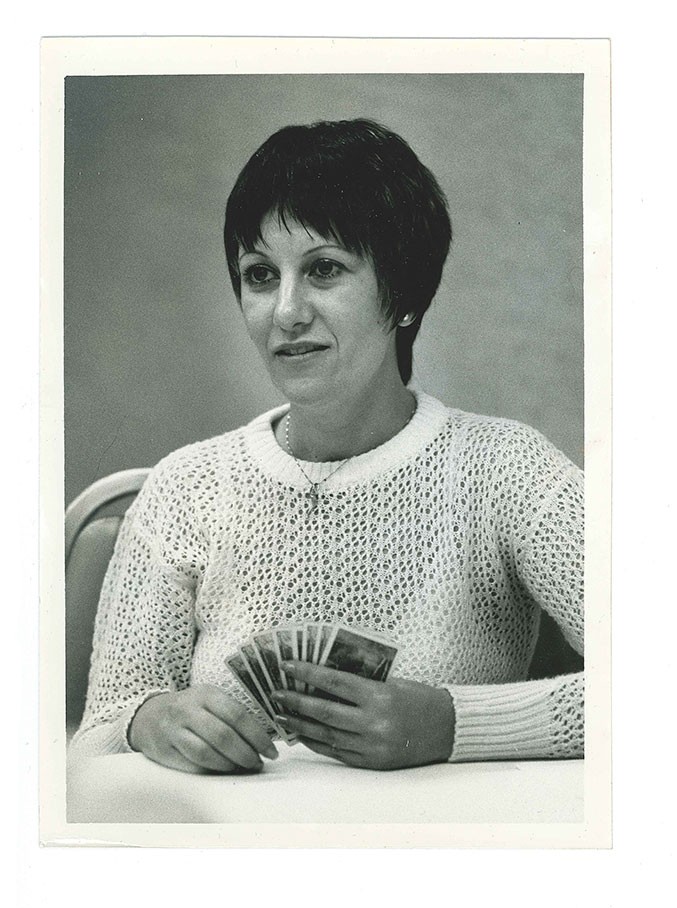

Charles Palmer

Julie O’Neill Playing Cards

September 1981

7 x 5 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

Chess Life Vol. 45, No. 10

October 1990

10 3/4 x 8 1/4 in.

Periodical

Collection of Julie O’Neill

In September 1989, Julie O’Neill became the first woman editor of Chess Life. Presented in this case is one of her favorite articles, an interview with 2004 World Chess Hall of Fame inductee Anatoly Karpov, along with a photograph of her from 1981.

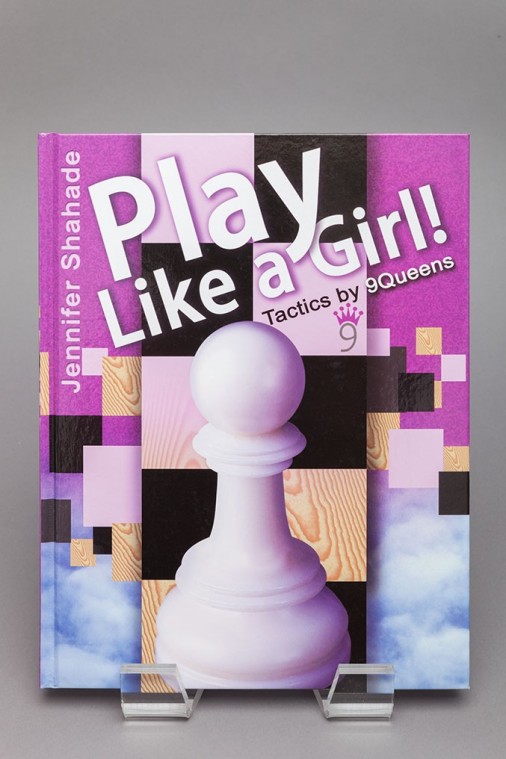

Jennifer Shahade

Play Like a Girl: Tactics by 9 Queens

2011

11 1/4 x 8 3/4 x 1/2 in.

Book

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Jennifer Shahade, 2002 U.S. Women’s Chess Champion, has built a career on a passion for the game. She has created chess-related artwork (one piece is on view in the World Chess Hall of Fame’s current exhibition Ladies’ Knight: A Female Perspective on Chess that explores issues of gender), served as a commentator for the U.S. and U.S. Women’s Chess Championships as well as the Sinquefield Cup, and written two books that discuss women’s chess history. Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport (2005) blends autobiographical elements with research and interviews with prominent female players, while Play Like a Girl! Tactics by 9 Queens (2011) teaches tactics using games by female players. Shahade also contributed to Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Chess (2009).

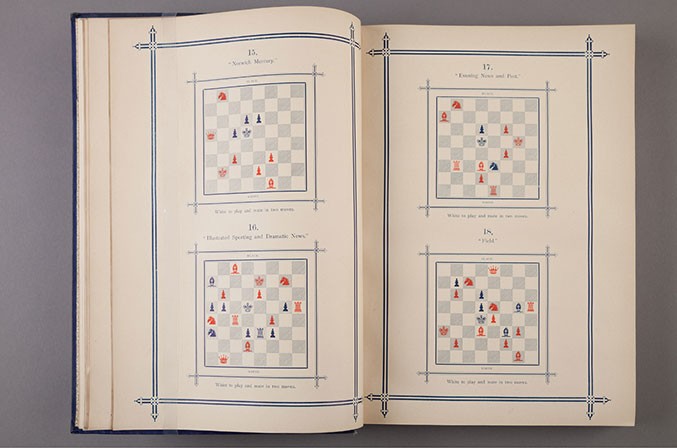

Edith (Mrs. W.J.) Baird

700 Chess Problems

1902

11 3/16 x 8 x 1 1/8 in.

Book

John G. White Chess Collection at the Cleveland Public Library

This volume collects chess problems composed by Edith Baird, one of the most well-known chess problem composers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Newspapers published her compositions, and she also competed in chess composition contests, sometimes against men. Baird also published another book of chess problems titled The Twentieth Century Retractor, Chess Fantasies, and Letter Problems Being a Selection of Three Hundred Problems (1907). The book paired chess problems with quotes from the works of Shakespeare that corresponded with their set ups or solutions.

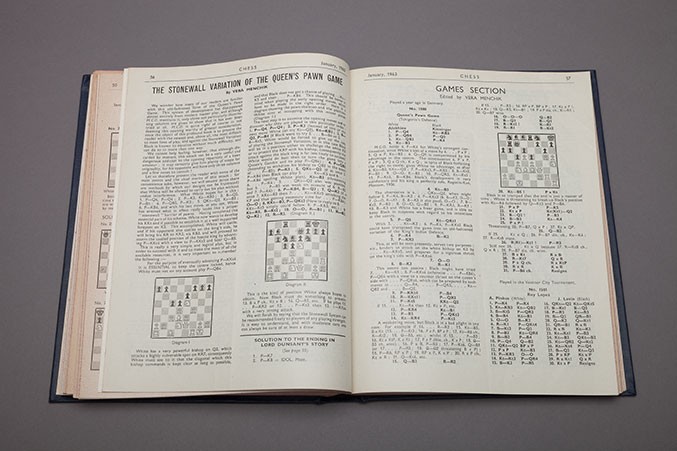

Vera Menchik

“The Stonewall Variation of the Queen’s Pawn Game”

Chess Vol. 8, No. 88

January 1943

9 3/8 x 7 1/4 x 1 1/8 in.

Bound periodical Collection of John Donaldson

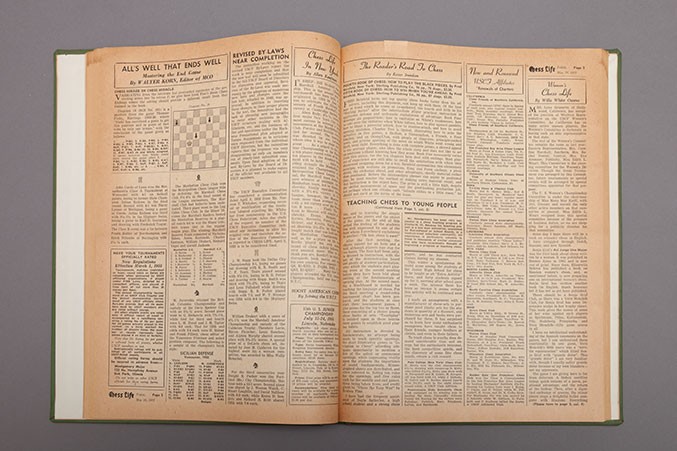

Willa White Owens

“Women’s Chess Life”

Chess Life Newspaper, Vol. 9, No. 12

May 20, 1955

13 1/8 x 9 7/8 in.

Bound Periodical

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

In this column for Chess Life, Willa White Owens reviews Sonja Graf’s autobiographical book Así juega una mujer (1941), which included many of her games. When introducing her book review, Owens wrote, “Some day I hope there will be a book on women’s chess in English. I have struggled through Dutch, Russian, and now Spanish.” Through her column, titled “Women’s Chess Life,” Owens aimed to help share news of women’s chess throughout the United States. First printed on February 20, 1955, Owens’s column printed information from both the national and local level, providing a lively record of chess in the 1950s and 1960s.

International Tournaments and Women’s World Championships

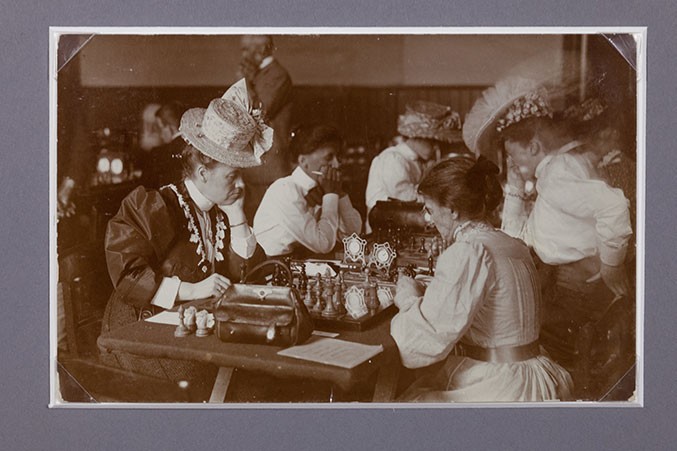

Photo Postcard from the 1906 British Ladies’ Chess Championship

1906

3 1/2 x 5 1/2 in.

Photograph

Collection of Richard Benjamin

Seated second from the right is Frances Herring, the winner of the 1906 British Ladies’ Chess Championship. At her left is Mary Houlding, who went on to win the championship in 1910/11 and 1914. The host of both the first international women’s chess competition and the first Women’s World Chess Championship, England fostered a lively women’s chess scene in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Bradshaw, Newgate-street

1897 International Ladies’ Chess Congress

July 10, 1897 8 x 5 5/16 in.

Reproduction

John G. White Chess Collection at the Cleveland Public Library

Organized by the Ladies’ Chess Club of London in honor of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, the 1897 International Ladies’ Chess Congress was the first international tournament for female players. 20 women from nine different countries (United States, Canada, Germany, Italy, Belgium, France, England, Scotland, and Ireland) competed in the tournament. Though criticisms rooted in sexism were aimed at the tournament, stating among other concerns that the players might “collapse with nervous strain at having to play two rounds a day for ten days,” the event, won by Mary Rudge, served as a forerunner to the Women’s World Chess Championship. Nevertheless, women-only chess tournaments have since come under fire due to the possibility that they may prevent women from achieving their full potential by preventing them from competing alongside male players with higher ratings.

W.S. Bradshaw & Sons

Mary Rudge

1897

4 3/16 x 6 1/2 in.

Reproduction

John G. White Chess Collection at the Cleveland Public Library

Mary Rudge, the winner of the 1897 International Ladies’ Chess Congress, poses confidently in this image taken the year of her victory. Rudge had distinguished herself as one of the best female players in England by the time of the tournament, competing in local women’s tournaments as well as competing with men. An August 1897 British Chess Magazine that recapped the events of the 1897 tournament quoted the words of an unnamed observer at the competition who declared, “She doesn’t seem to care so much to win a game as to make her opponent lose it.” Rudge had learned the game from her older sisters, who had been taught by their father.

Program from the 1937 Stockholm, Sweden, Women’s World Chess Championship

July 31-August 15, 1937

7 1/2 x 5 1/2 in.

Program

Collection of Allan Savage

Along with Mary Bain, Mona May Karff represented the United States in the Women’s World Chess Championship held in Stockholm, Sweden. She recorded the events of the tournament on this crosstable. Reigning Women’s World Chess Champion Vera Menchik defended her title for the second time that year, winning the double round robin tournament. She had previously defeated her rival Sonja Graf in a title match.

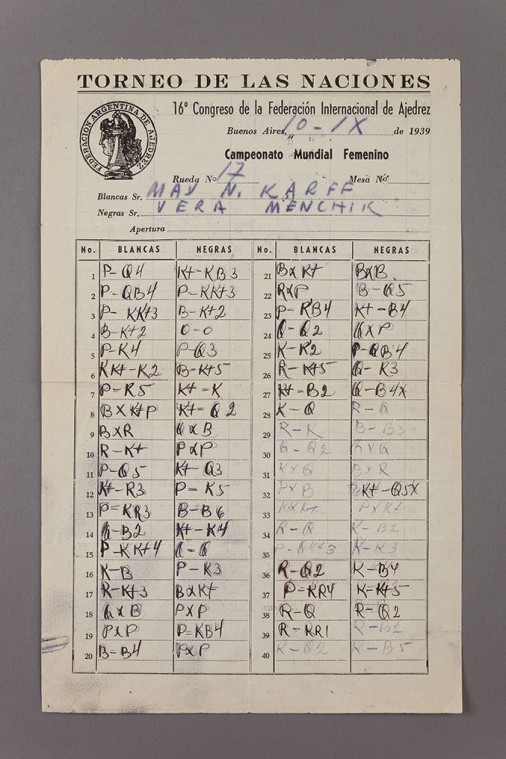

Score sheet from the 1939 Buenos Aires, Argentina, Women’s World Chess Championship: Mona May Karff vs. Vera Menchik

September 9, 1939

10 5/8 x 6 7/8 in.

Score sheet

John G. White Chess Collection at the Cleveland Public Library

This scoresheet records a game between American player Mona May Karff and then-reigning Women’s World Chess Champion, Vera Menchik. It was played in the final round of the 1939 Women’s World Chess Championship, the final title tournament before the competition went on hiatus during World War II.

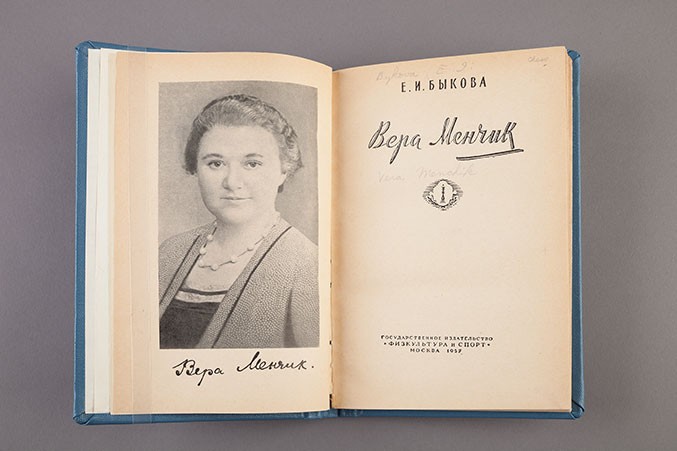

E.I. Bykova

Vera Menchik

1957

8 1/4 x 5 3/8 x 5/8 in.

Book

John G. White Chess Collection at the Cleveland Public Library

Written by Elizaveta Bykova, the third Women’s World Chess Champion, this book details the life of Vera Menchik. The publication emphasizes Menchik’s Russian heritage in an effort to promote women’s chess in the Soviet Union. It also details a trip that Menchik made to the country in 1935. Passionate about women’s chess, Bykova also wrote two other books about Soviet women chess players and the Women’s World Championship.

Photographer unknown

Competitors in the 1949/50 Moscow, Russia, Women’s World Chess Championship

December 1949-January 1950

9 3/16 x 3 9/16 in.

Reproduction

John G. White Chess Collection at the Cleveland Public Library

In this composite photo, 2003 World Chess Hall of Fame inductee Mikhail Botvinnik, then the reigning World Chess Champion, is pictured with some of the competitors in the 1949/50 Women’s World Chess Championship. Lyudmila Rudenko, one of the 2015 inductees to the World Chess Hall of Fame, won the competition. While some of the people featured in the photo were present at the time it was taken, other images were clearly added later.

Gisela Gresser’s Tournament Hall Pass 1949/1950 Moscow, Russia, Women’s World Chess Championship

1949

2 1/2 x 3 5/8 x 3/16 in.

Hall pass

John G. White Chess Collection at the Cleveland Public Library

This tournament pass, which lists the times and dates of tournament games, affirmed that Gisela Gresser was a participant in the 1949/1950 Women’s World Chess Championship. The pass is signed by a Soviet official. The pass additionally names the tournament location and address.

Photo by Michael DeFilippo

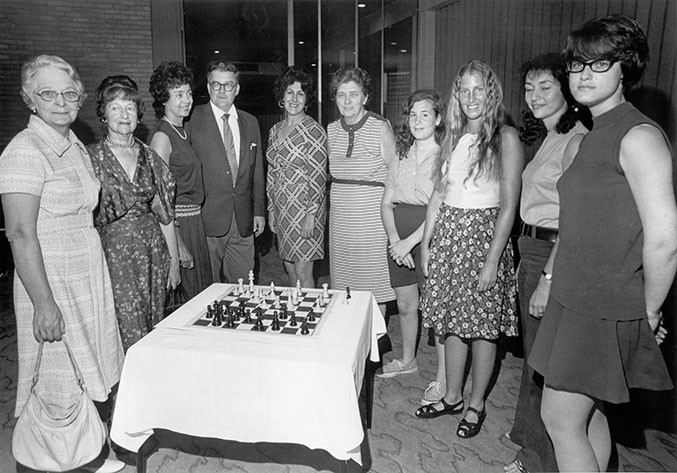

St. Petersburg Times and Evening Independent Competitors in the 1972, St. Petersburg, Florida, U.S. Women’s Chess Championship

1972

8 1/8 x 10 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

Pictured from left to right are competitors in the 1972 U.S. Women’s Chess Championship along with officials: Eva Aronson, Gisela Gresser, Bette Wimbish (vice mayor of St. Petersburg), Bob Braine (tournament director), Rachel Guinan, Mabel Burlingame, Rachel Crotto, Susan Sterngold, Joan Schmidt, and Marilyn Braun. 1972 marked the first year that future U.S. Women’s Chess Champion, Rachel Crotto, who was only 13 at the time, competed in the tournament.

Event Program from the 1991 Highland Beach, Florida, U.S. Women’s Chess Championship

August 17-24, 1991

11 x 8 1/2 in.

Program

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

1989 U.S. Women’s Chess Champion Alexey Root graces the cover of the 1991 U.S. Women’s Chess Championship program. Esther Epstein and Irina Levitina shared first place in the competition. In an article for Chess Life, Levitina noted that:

“WGMs Elena [Akhmilovskaya] Donaldson and Anna Achsharamurova declined to participate, a point worth comment. The U.S. Championship is the only annual women’s tournament in the United States. The prizes are good and all the expenses are paid by the American Chess Foundation and the USCF. One can’t imagine better conditions for the players and still, two of the potential winners elected not to play. It may only mean that a woman player can’t make a good living playing chess, and, whenever a good job opportunity in another field comes along, chess is given up; in three to five years, such a player won’t be able to compete with the real professionals from other countries. There is a risk of losing all the leading women chessplayers. To avoid this situation, something must be done.”

She further went on to speculate that perhaps more women’s prizes needed to be offered in open tournaments that included male players.

Nancy Roos

Gisela Gresser and Arnold Denker at the 1944 New York City, New York, U.S. and U.S. Women’s Chess Championships

1944

10 1/2 x 13 1/2 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Pictured from left to right in this photo taken after the 1944 U.S. and U.S. Women’s Chess Championships are: Edward Lasker, 1992 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Gisela Gresser, 1986 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Reuben Fine, 2010 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Herman Steiner, Carolyn Marshall, 1989 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee I. A. Horowitz, 1986 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Frank Marshall, and 1992 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Arnold Denker. In the photo, Gisela Gresser, the U.S. Women’s Chess Champion, and Arnold Denker, the U.S. Chess Champion, play a friendly game.

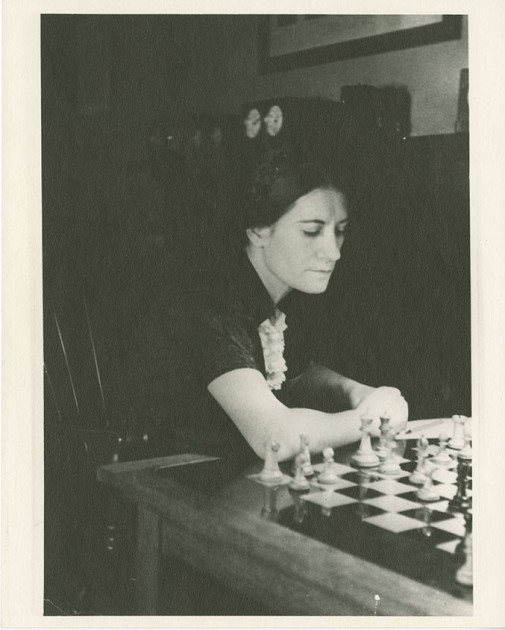

Nancy Roos

Nancy Roos

Date unknown

8 x 10 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

In this self-portrait, Nancy Roos moves her king in a game against an unknown opponent. Roos was not only a talented player, but also a professional photographer whose work appeared frequently in Chess Review, Chess Life, and the California Chess Reporter. Roos tied with Gisela Gresser for first in the 1955 U.S. Women’s Chess Championship, but only two years later tragically died of cancer at age 51.

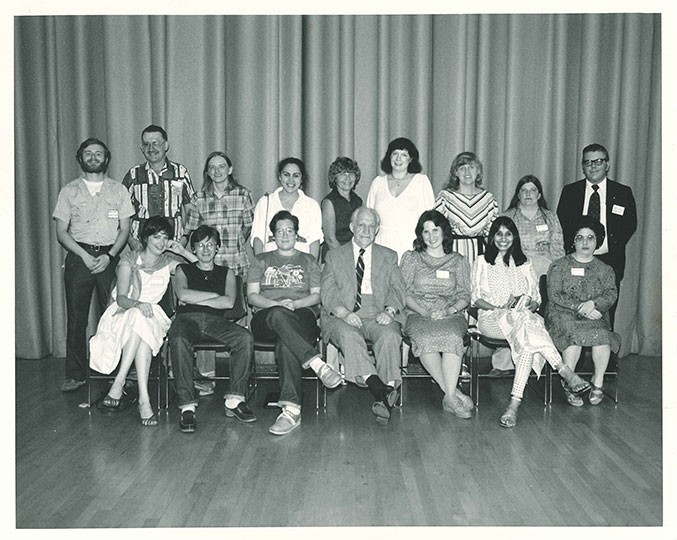

Photographer unknown

Competitors in the 1984 Berkeley, California, U.S. Women’s Chess Championship

1984

7 1/2 x 9 1/2 in.

Reproduction Courtesy of Alexey Root