Showcasing some of the most unique, historic, and fun artifacts acquired during the past five years, Open Files II: Celebrating 5 Years of Collecting includes 100 diverse objects from the World Chess Hall of Fame’s permanent collection.

Though it has only been in Saint Louis for five years, the WCHOF has a 30-year history spanning four locations throughout the United States. Open Files II is the second part of an exhibition cycle in our third floor gallery that shows how the WCHOF’s collection has grown in the time since its relocation from Miami to Saint Louis.

Highlights include materials related to the Saint Louis launch of the Boy Scouts of America chess merit badge; a rare Hungarian chess set made from sterling silver, amethyst, jade, pearls, and copper donated by the Traci L. and Arthur B. Laffer family; a gold medal from the 2016 Chess Olympiad (the first won by the American team in 40 years), chess-inspired artwork by Rafael Tufiño; and artifacts related to the career of computer chess pioneer, World Correspondence Chess Champion, and 1990 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Hans Berliner.

On view: April 27 – October 29, 2017

Artifacts featured in the Exhibition

Chess Olympiads are competitions that feature teams representing different national chess federations. The first unofficial Chess Olympiad occurred in Paris in 1924, and the first official Olympiad took place in London in 1927. Thirty years later, the first Women’s Chess Olympiad took place in Emmen, the Netherlands. Competitors can win medals both for their performances as a team or as individuals. The United States has a tradition of success in the biennial Chess Olympiad. Teams in the 1930s took first four times (1931, 1933, 1935 and 1937), and Grandmaster Bobby Fischer (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 1986; World Chess Hall of Fame, 2001) played on two silver medal-winning teams (1960 and 1966). More recently (1974-2016), the U.S. took first twice, second twice, and third eight times. Overall, the United States has won more Olympiad team medals than any other country except for Russia/the Soviet Union.

Commemorative Azerbaijani Rug Chessboard from the 2016 Baku, Azerbaijan, Chess Olympiad

2016

18 1⁄4 x 16 in.

Chessboard

Gift of Mike Klein

Chess Olympiads offer opportunities for their host countries to promote their history and culture. FIDE Master Mike Klein received this decorative chessboard as a gift while covering the events of the 2016 Baku, Azerbaijan, Chess Olympiad. The board promotes the region’s long history of carpet weaving, which the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) declared to be an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2010. The border of this carpet chessboard has eight pointed stars, a common motif on these works.

Grandmaster Walter Browne’s Team Bronze Medal from the 1974 Nice, France, Chess Olympiad

1974

17 5⁄8 in x 2 1⁄2 in.

Medal with ribbon

Gift of Raquel Browne

The 1974 Nice, France, Chess Olympiad (June 6-30), celebrated the 50th anniversary of the World Chess Federation (Fédération Internationale des Échecs, or FIDE). Grandmaster (GM) Walter Browne was a member of the American team, which also included GMs Lubomir Kavalek (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 2001), Robert Byrne (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 1994), Samuel Reshevsky (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 1986), William Lombardy, and International Master James Tarjan. The group took team bronze in the competition, behind the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia.

FIDE

International Master John Donaldson’s Team Bronze Medal from the 2006 Turin, Italy, Chess Olympiad

2006

3⁄16 x 2 5⁄16 in. dia.

Medal with ribbon

Gift of John Donaldson

International Master John Donaldson earned this team bronze medal for his role as team captain in the 2006, Turin, Italy, Chess Olympiad (May 20–June 4). Grandmasters (GMs) Hikaru Nakamura and Varuzhan Akobian made their debuts in the competition, joining a team that also included GMs Gata Kamsky (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 2016), Alexander Onischuk, and Yury Shulman.

FIDE

International Master John Donaldson’s Team Gold Medal from the 2016 Baku, Azerbaijan, Chess Olympiad

2016

1⁄4 x 2 5⁄16 in. dia.

Medal with ribbon

Gift of John Donaldson

The 2016 Chess Olympiad marked both the first time the American team had won team gold in the Open Section in an Olympiad with Russian/Soviet competitors, and the first time the United States had won team gold in the Olympiad in 40 years. The team consisted of Grandmasters Fabiano Caruana, Hikaru Nakamura, Ray Robson, Sam Shankland, and Wesley So, with Aleksandr Lenderman as team coach. International Master John Donaldson, who donated this medal, was the team captain.

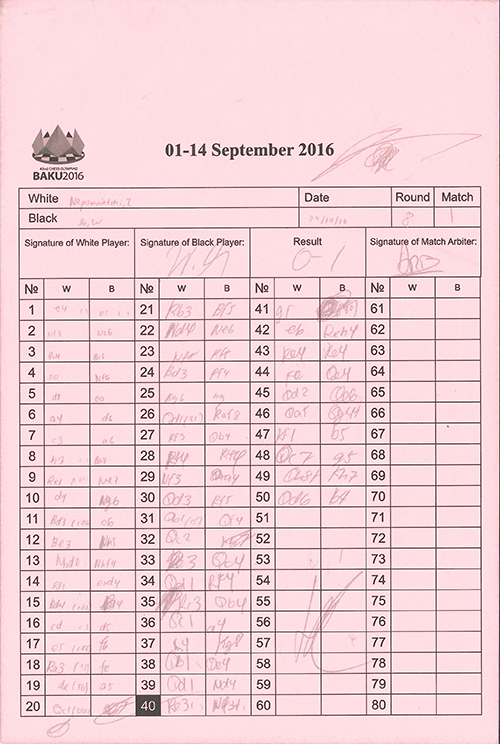

Score Sheet from Round 8 of the 2016 Baku, Azerbaijan, Olympiad: Grandmaster Ian Nepomniatchi vs. Grandmaster Wesley So

September 10, 2016

10 5 ⁄16 x 6 7⁄8 in.

Score sheet

Gift of John Donaldson

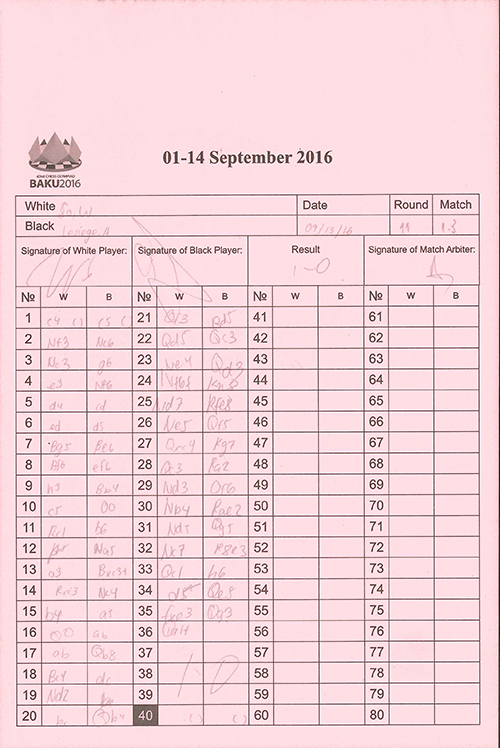

Score Sheet from Round 11 of the 2016 Baku, Azerbaijan, Olympiad: Grandmaster Wesley So vs. Grandmaster Alexandre Lesiège

September 13, 2016

10 5 ⁄16 x 6 7⁄8 in.

Score sheet

Gift of John Donaldson

The 2016 first-place winning United States Olympiad team finished ahead of 169 other teams from around the world. American Grandmaster (GM) Wesley So played a key role on board three, winning individual as well as team gold. These score sheets are from two important games. The first is So’s round eight win over Russian GM Ian Nepomniatchi which ended the latter player’s seven-game winning streak. The second is So’s dramatic final round game against GM Alexandre Lesiège.

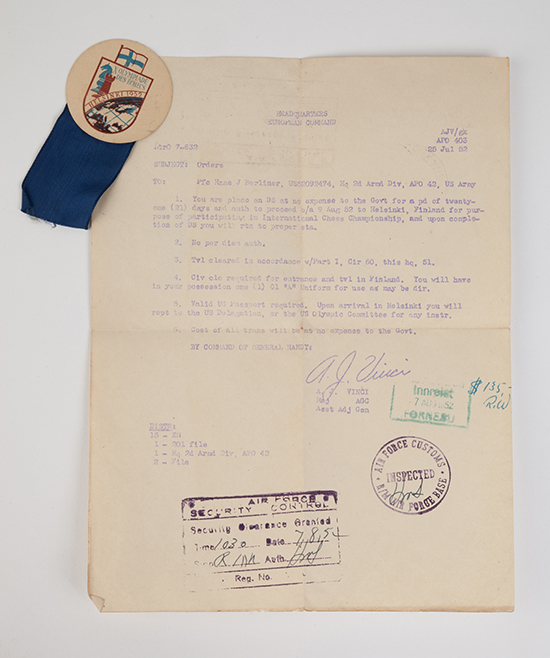

Hans Berliner’s Letter of Clearance from the United States Army Air Force Allowing Him to Participate in the 1952 Helsinki Chess Olympiad

July 25, 1952

10 7⁄16 x 7 15 ⁄16 in.

Correspondence

Gift of Carl Ebeling

Pin from the 1952 Helsinki Chess Olympiad

1952

3 13⁄16 x 2 in.

Pin

Gift of Carl Ebeling

In 1952, Hans Berliner (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 1990), was serving in the United States Army Air Force when he was invited to be part of the 1952 U.S. Chess Olympiad team. He sought and received leave to travel to Helsinki, Finland, to compete as part of the team, which ultimately took fifth place.

Grandmaster Walter Browne’s Team Bronze Medal from the 1984 Thessaloniki, Greece, Chess Olympiad

1984

Medal: 3 ⁄16 x 1 15 ⁄16 in. dia. Box: 1 x 3 15⁄16 x 2 3⁄4 in.

Medal with box

Gift of Raquel Browne

A dominant force in American chess, Grandmaster (GM) Walter Browne (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 2003) won six U.S. Championships, a feat only surpassed by GMs Samuel Reshevsky and Bobby Fischer. He earned renown as a tactician whose perfectionist nature sometimes led him into time pressure. However, his success was not confined to the national stage. He represented the United States in four Chess Olympiads, earning team bronze four times and individual bronze once.

Bertoni S.R.L. Milano

Grandmaster Walter Browne’s Individual Bronze Medals from the 1972 Skopje, Yugoslavia (present-day Republic of Macedonia), Chess Olympiad

1972

Medals: 2 1⁄16 in. dia.

Stand: 4 1⁄2 x 6 1⁄4 x 1⁄2 in.

Medals mounted on velvet and leather stand

Gift of Raquel Browne

Before representing the United States in the Chess Olympiad, Grandmaster Walter Browne twice competed on behalf of Australia. In 1972, Browne earned an individual bronze medal for his efforts. The medals on view here are part of his archive, which Browne’s wife Raquel donated to the World Chess Hall of Fame after his 2015 death.

FIDE

Walter Korn’s Honorary Medal from the 1964 Tel Aviv, Israel, Chess Olympiad

1964

Medal: 3 ⁄16 x 2 5 ⁄16 in. dia.

Box: 1 x 3 1⁄2 x 2 3⁄4 in.

Medal with box

Gift of John Donaldson

Though best remembered as the editor of several editions of Modern Chess Openings (1952-1990), Walter Korn was also an accomplished endgame expert. Korn was awarded the title of FIDE Judge for Chess Composition at the 1964 Tel Aviv, Israel, Chess Olympiad. Endgame studies and chess problems (mates in three, for example) are among the items that Korn evaluated as a FIDE Judge for Chess Composition.

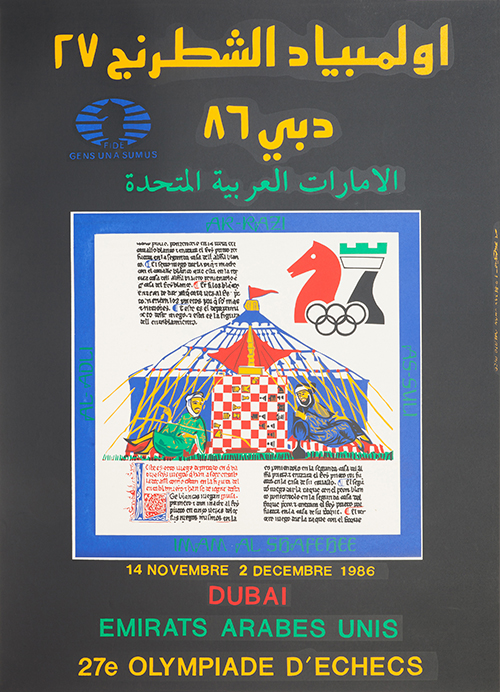

Rafael Tufiño

Chess Olympiad, November 14-December 2, 1986. Dubai

1986

34 15/16 x 22 15/16 in.

Poster

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Hungary

Silver and Copper Enamel Chess Set and Board

Early 20th century

King size: 3 1⁄2 in.

Board: 22 x 22 x 2 3⁄4 in.

Silver, copper, enamel, pearls, jade, amethyst, and wood

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the Traci L. and Dr. Arthur B. Laffer family

One of the finest pieces in the collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, this chess set is part of a centuries-long tradition of intricate Hungarian metal and enamel work. Made of sterling silver and copper and adorned by jade, amethyst, and natural pearls, the chess set depicts two warring armies, but is intended for display as a work of art rather than play. On the corners of the board, warriors holding spears stand at the ready. The sides of the board include enamelwork images of battles and coats of arms. Special care has even been taken to the storage space within the board box—metal chains cradle each of the pieces.

While the World Chess Hall of Fame’s collection of chess sets includes sets made from fine materials (like the Hungarian chess set also displayed in this exhibition), many others are either mass-produced with pop culture themes or handmade by chess enthusiasts. This case contains several examples of the latter category—from a set made from recycled bookbinding materials to one created in a storied tradition of Russian ceramic production. Many of these sets tell stories about their creators, the groups that commissioned them, or larger trends in the societies in which they were created.

Creator unknown (inscribed MAD on base)

Arctic Chess Set

1988

King size: 5 1⁄4 in.

Board: 16 x 15 3⁄4 in.

Ceramic and wood

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

A man and woman lead a team of arctic animals, which includes bears, wolves, and seals in this set inspired by 20th-century soapstone sets created by Inuit artists for tourists. An individual created this set using molds that were mass produced by a craft company. The pieces were painted with colors chosen by its maker.

Clarence B. Lester

Clarence B. Lester’s Homemade Pocket Chess Set

c 1892

6 1⁄4 x 11 1⁄2 in.

Recycled bookbinding materials and ink on paper

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Clarence B. Lester

Clarence Brown Lester, a future inductee to the Wisconsin Library Association Hall of Fame, created this travel chess set while in high school. The simple set is made from recycled materials, and the board’s squares are created in ink. Lester also created a scrapbook of chess articles from the Providence Free Journal using similar improvised materials. The Wisconsin Library Association Hall of Fame inducted Lester in 2012 for his tenure as the longest serving Secretary to the Wisconsin Free Library Association (1920-1949). Margaret Weinstein, Lester’s granddaughter, donated the set to the World Chess Hall of Fame in 2017 in his memory.

Yury Garanin

Chess Collectors International Gzhel Teapot Chess Set

1996

King size: 1 3⁄8 in.

Board: 7 1⁄2 x 7 1⁄2 x 3 1⁄2 in.

Chess set

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Courtesy of exclusive distributor of all Gzhel products in the United States and Canada: St-Petersburg Global Trade House

A miniature coffee and tea service forms the pieces in this collectible set produced for Chess Collectors International (CCI), an organization founded in 1984 to bring together people passionate about collecting chess sets and ephemera. The World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) often works with the organization’s Western Hemisphere Group and has twice hosted its meetings. The first, in 2011, coincided with the opening of the WCHOF in Saint Louis, and the second was in 2015 during the second Sinquefield Cup Tournament, an elite chess competition held at the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis. The organization’s logo appears at the center and sides of the board. The blue and white set is a distinctive style of Russian ceramics called Ghzel, named for the village of Ghzel. Yury Garanin, the creator of this set, is a member of the Ghzel Association, known for miniatures, chess sets, and coffee services.

Dick Johnson

Marching Band Chess Set

Date unknown

King size: 3 5⁄8 in.

Board: 14 x 14 x 2 in.

Wood and linoleum tiles

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

In this homemade chess set, each of the hand carved figures represents a member of a marching band. A drum major and majorette lead each side as the king and queen, while the bishops carry glockenspiels, the knights hold trombones, and the rooks pound drums. Each of the pawns carries a different instrument. The set highlights the ingenuity of its creator—the squares on the board are made from mid-century style floor tiles.

Howard Staunton

The Chess Player’s Handbook

1847

7 1⁄2 x 4 11⁄16 x 1 5⁄16 in.

Book

Gift of Bill Merrill

Howard Staunton was one of the best players of the 1840s and eventually worked to standardize rules of chess across nations. Staunton popularized his ideas in a series of books and organized the first modern international tournament (London, 1851). The now-standard tournament chess piece design, first produced by Jaques of London and which Staunton helped to popularize, bears his name.

Emanuel Lasker’s Portable Chess Set

Date unknown

King size: 3⁄4 in.

Board: 9 x 7 1⁄2 x 1 1⁄4 in.

Chess set

Gift of the DeLucia Family Foundation, partial and promised gift of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

The second and longest-reigning World Chess Champion, Emanuel Lasker was one of the first individuals inducted to the World Chess Hall of Fame upon its creation in 2001. This humble travel chess set belonged to him and is part of a donation of archival materials related to the chess legend, which include manuscripts, letters, and other ephemera.

Boy Scouts of America Coin

2011

Box: 2 7⁄8 x 3 1⁄2 x 3 5⁄16 in.

Coin: 1 11⁄16 in. dia.

Coin

Gift of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

This coin celebrates Dr. Jeanne Sinquefield for her role in creating the Boy Scouts of America chess merit badge. The chess merit badge was discussed for 40 years, but never completed until she pushed for it to be made a reality. Scouts must learn chess rules, history, benefits, and etiquette to earn the badge.

American Chess Equipment

Signed Yasser Seirawan Trading Card

April 2001

4 x 2 15⁄16 in.

Trading Card

Gift of John Donaldson

This autographed “rookie card” celebrates the career of Grandmaster Yasser Seirawan (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 2006). Seirawan is a four-time U.S. Chess Champion, a member of ten U.S. Chess Olympiad teams, and two-time candidate for the World Chess Championship. He is also a frequent presence on the Saint Louis Chess Campus, serving as Grandmaster in Residence at the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis and as part of the commentary team for tournaments.

Dan Martin

Boy Scouts of America Caricature of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

2011

15 1⁄8 x 12 1⁄8 in.

Photomechanical print

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame,

gift of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

St. Louis Post-Dispatch cartoonist Dan Martin created a caricature of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield at the opening of the World Chess Hall of Fame in 2011, which coincided with the September 10, 2011, launch of the Boy Scouts of America Chess Merit Badge. Dr. Jeanne is shown saluting and holding the Chess Merit Badge, with Rex doffing his baseball cap and holding the giant king chess piece outside the World Chess Hall of Fame entrance.

Boy Scouts of America Chess Merit Badge

2011

1 7⁄16 in. dia.

Merit badge

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

©Chess2Go

Chess2Go

2013

King size: 1 3⁄8 in. dia.

Board: 15 x 15 in.

Chess set

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis

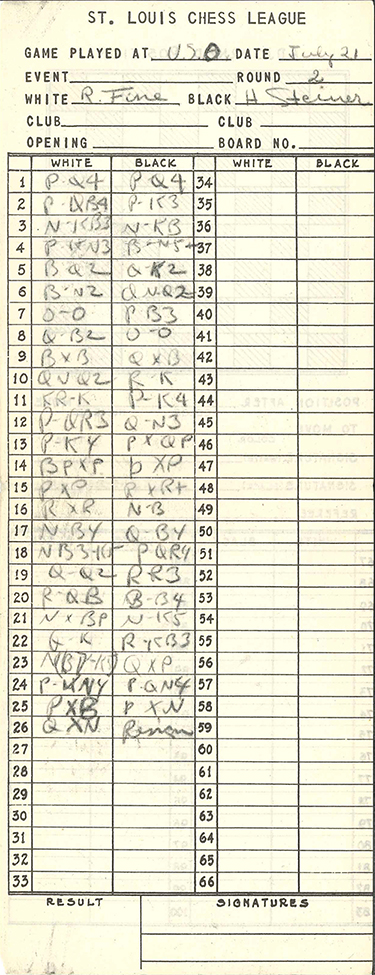

Score Sheet from Round 2 of the 1941 Saint Louis U.S. Open: Grandmaster Reuben Fine vs. International Master Herman Steiner

July 21, 1941

10 11⁄16 x 4 1⁄8 in.

Score sheet

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

The deciding game of the 1941 U.S. Open, held July 17-24 at the Hotel Desoto in Saint Louis, was won in fine style by Reuben Fine (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 1986) against Herman Steiner (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 2010). Fine earned first place in the event with Steiner finishing second. This game was analysed extensively in Fine’s Lessons From My Game, a collection of his best games published in 1958.

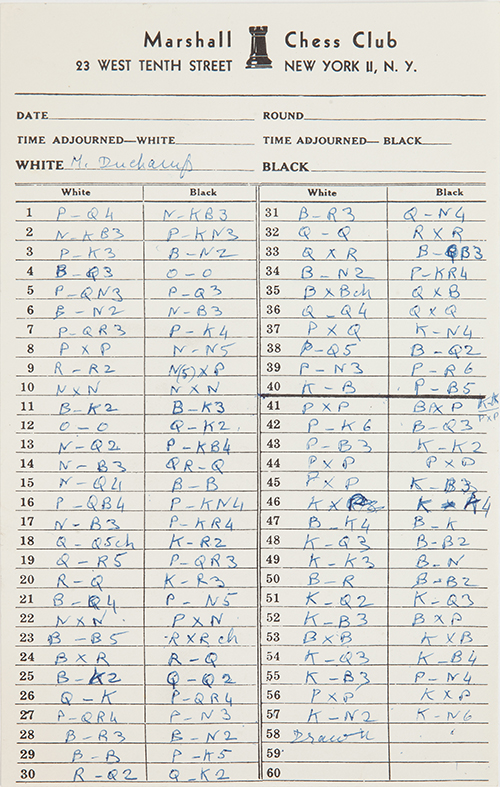

Score Sheet from a 1961 Game at the Marshall Chess Club in New York City: Marcel Duchamp vs. Jacqueline Piatigorsky

November 11, 1961

8 5⁄16 x 5 1⁄4 in.

Score sheet

Gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

In her memoir Jump in the Waves (1988), Jacqueline Piatigorsky said, “In chess one deals with a cross-section of people. I played with a gardener, and I played with Marcel Duchamp and Prokofiev.” The 2013 donation of the archive of Jacqueline Piatigorsky, a top U.S. Women’s Chess Championship player, a visionary tournament organizer, and chess philanthropist, was one of the first significant acquisitions of the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF). She competes against artist and chess master Marcel Duchamp, whose legacy inspires many of the exhibitions presented at the WCHOF since its relocation to Saint Louis in 2011.

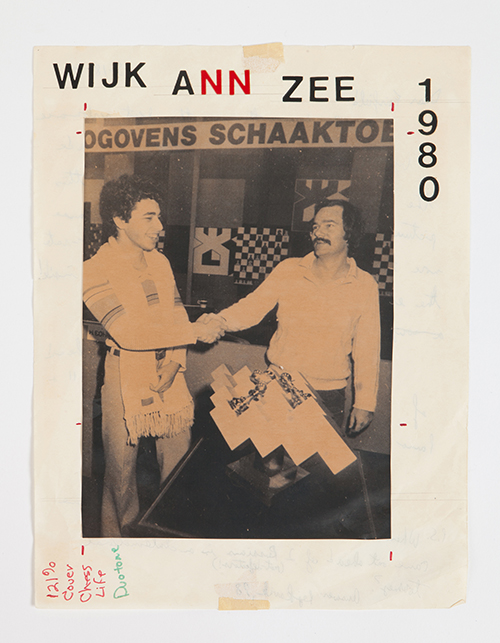

Letter from Grandmaster Walter Browne to Fairfield W. Hoban

May 18, 1980

11 x 8 1⁄2 in.

Photograph mounted on paper

Gift of Raquel Browne

In this letter, six-time U.S. Chess Champion Walter Browne (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 2003) recounts the exciting events of the 1980 Hoogovens International Tournament (today known as Tata Steel) in Wijk aan Zee, the Netherlands. He suggests reproducing a photograph of himself with 19-year-old Yasser Seirawan (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 2006) on the cover of the August 1980 issue of Chess Life and Review. Seirawan, a future 4-time U.S. Chess Champion, shared first place with Browne, triumphing over opponents who included Grandmaster Viktor Korchnoi (World Chess Hall of Fame, 2017). This performance earned Seirawan his final grandmaster norm.

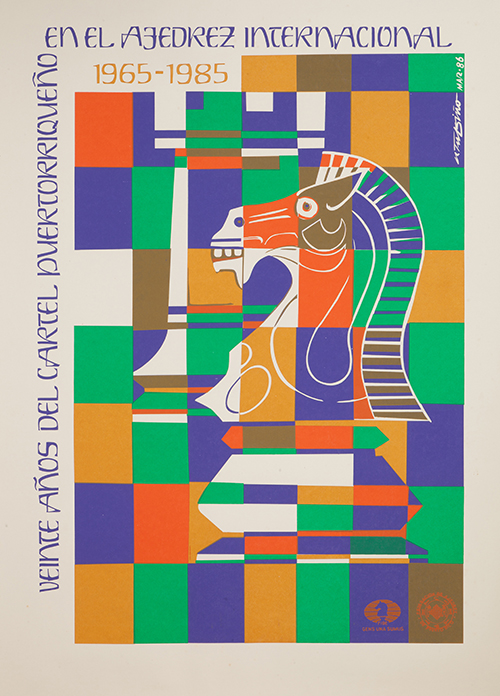

Rafel Tufiño

Twenty Years of the Puerto Rican Poster in International Chess

1986

30 x 23 1/8 in.

Serigraph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

© 2017 Sucesión R. Tufiño

Rafael Tufiño

40th World Chess Congress

1969

27 1/2 x 19 1/2 in.

Serigraph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

© 2001 Sucesión R. Tufiño

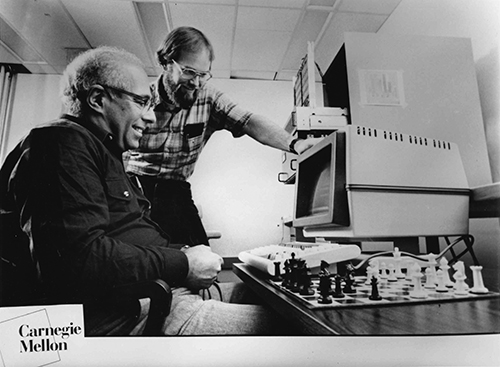

Bill Redic

Hans Berliner and Carl Ebeling with the Hitech Chess Computer

c 1985

7 7⁄8 x 9 7⁄8 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Carl Ebeling

Carl Ebeling and Hans Berliner pose with Hitech in this photograph, which was featured in Carnegie-Mellon Magazine’s 1985 article “‘Hitech’ and the Chess Master Who Wants to Lose.” The magazine recounted Hitech’s victory with a perfect score in the recent 1985 North American Computer Chess Championship as well as its development. Hitech began as an “area qualifier project” of Carl Ebeling while he was a doctoral student at the university. He custom-designed the chips that Hitech used as evaluate moves, and the computer could search 175,000 positions/second. Berliner developed means of improving the search algorithms of the machine.

Berliner’s interest in chess computers united his work with computer programming with his passion for chess. Chess intrigued computer scientists of the time because it allowed them to test concepts in the field of artificial intelligence using a game of strategy with defined rules. Murray Campbell, who developed Deep Blue, the computer that famously defeated Garry Kasparov (World Chess Hall of Fame, 2005), later said that though it was originally expected that computer chess would allow insights into human intelligence, this research instead, “led to a change of mind, a change in attitude, about how we approached a number of problems in computer science. And in this field—and this is an important point—Hans Berliner produced something that had lasting value.”

Sport Center

Hans Berliner’s Third Place Trophy from the 1964 Boston, Massachusetts, Eastern Open

1964

14 1⁄16 x 6 x 3 3⁄8 in.

Wood and bronze

Trophy

This trophy is an award from one of the regional chess tournaments in which Berliner, a four-time competitor in the U.S. Chess Championship (1954, 1957, 1960-61, and 1962-63), participated. In a May 2012 interview with Jason Togyear for Link Magazine, Berliner said of chess, “You’re forced to deal with a certain level of reality… It’s up to you to do something that improves your prospects in a certain way.”

International Correspondence Chess Federation (ICCF)

Hans Berliner’s International Correspondence Chess Federation World Champion Medal

1968-1971

1 15⁄16 in. dia.

Medal

ICCF

Hans Berliner’s International Correspondence Chess Federation Grandmaster Medal

1968

1 15⁄16 in. dia.

Medal

This pair of medals celebrate two notable accomplishments in Hans Berliner’s correspondence chess career—his earning the title of International Correspondence Chess Federation (ICCF) Grandmaster winning the fifth ICCF World Chess Championship. Founded in 1951, the ICCF organizes the World Correspondence Chess Championship. At the time that Berliner won the Championship, players submitted moves by mail, but today, correspondence chess is often played on web servers or by email.

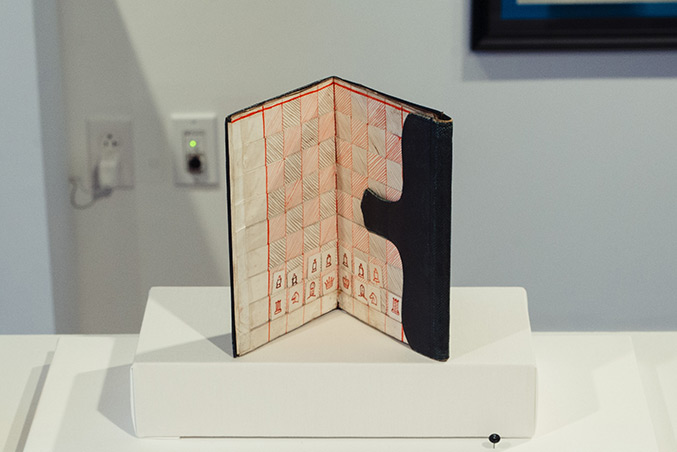

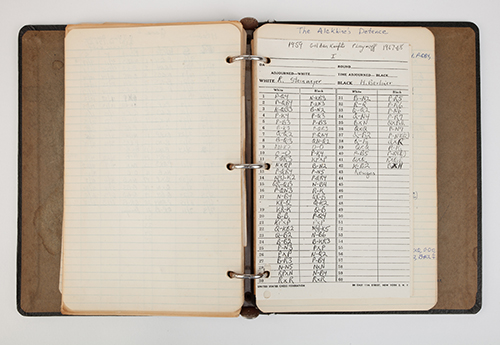

Hans Berliner’s Notebook

1944-1963

9 15⁄16 x 15 ½ in.

Notebook

Berliner started playing chess by mail in his early teens. His win over Soviet player Yakov Estrin, on the black side of the Two Knights Defense, is considered by many, including Grandmaster Andrew Soltis (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 2011) to be the greatest correspondence game ever played. This notebook contains Berliner’s handwritten notes about the Two Knights Defense as well as records of his correspondence chess games.

Allen Newell Award for Research Excellence

1988

Medal: 1 3⁄16 in dia.; Overall: 20 x 3 ¼ in.

Medal

The Allen Newell Award for Research Excellence recognizes, “an outstanding body of work that epitomizes Allen Newell’s research style as expressed in his words: ‘Good science responds to real phenomena or real problems; good science is in the details; and good science makes a difference.’ Newell was a Professor of Computer Science at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), where Hans Berliner attended graduate school and was one of his students. After receiving his PhD in 1974, Berliner worked as a professor at CMU and went on to develop Hitech. This medal celebrates his accomplishments in creating the first chess computer to reach the level of Senior Master.

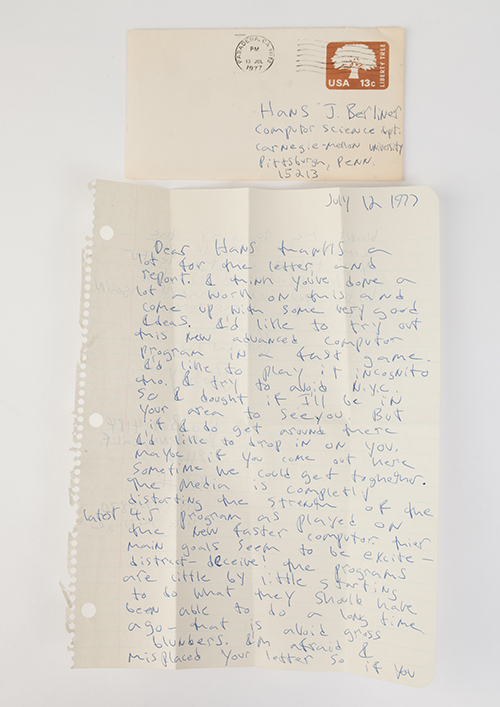

Letter from Bobby Fischer to Hans Berliner

July 12, 1977

Letter: 11 x 8 3⁄8 in.

Document

In this letter, Bobby Fischer expresses his gratitude to Hans Berliner for his assistance with his inquiries about computer chess programs and expresses his desire to play against Hitech. Until his 1992 rematch of the 1972 World Chess Championship match against Boris Spassky, the only new Fischer games published were played against Robert Greenblatt’s Mac Hack IV computer in 1977. Fischer won each of their three games. It is unknown whether Fischer ever played a game with Hitech.

Photography by Michael DeFilippo and Austin Fuller

Downloads

Open Files II Exhibition Brochure

Press

8/15/2017: Wall Street International — Open Files II

4/27/2017: STL Magazine — Opening Reception: Open Files II: Celebrating 5 Years of Collecting

4/27/2017: AARP — Exhibition – Open Files II: Celebrating 5 Years of Collecting

4/11/2017: Press Release