Open Files: Celebrating 5 Years of Collecting highlights just a small portion of the numerous artifacts the World Chess Hall of Fame has obtained during its first five years in Saint Louis.

On View: September 29, 2016 – April 15, 2017

One of the first exhibitions presented at the World Chess Hall of Fame’s (WCHOF) Saint Louis location was a survey of highlights from the permanent collection and loans from other institutions. Open Files revisits this concept, honoring some of the donors from the past five years as well as illustrating the diversity of its collection.

The World Chess Hall of Fame has a 30-year history spanning four locations throughout the United States. During these years, varied individuals—inductees to the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, chess set collectors, enthusiasts, and WCHOF staff—donated to and shaped the collection. Founded in 1986, the institution was first known as the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame. Two years later its first physical location opened in the then-headquarters of the United States Chess Federation (now U.S. Chess) in New Windsor, New York. The first items from the collection displayed in this location were plaques honoring the new inductees to the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, along with artifacts related to their accomplishments. Later locations in Washington, D.C., and Miami, Florida, expanded both the mission and the scope of collecting. In Miami, the museum became known as the World Chess Hall of Fame and Sidney Samole Museum, and featured an expanded mission to honor international as well as national chess luminaries. There, many artifacts from the collection were included in permanent displays illustrating the history of chess across the globe and honoring the accomplishments of inductees to the U.S. and World Chess Halls of Fame.

After the Miami museum’s 2009 closing, the fate of the collection hung in limbo, as artifacts were put in storage. Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield, who had founded the not-for-profit Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis (CCSCSL) the previous year, provided the funding to move the WCHOF to Saint Louis and along with it, the collection. Staff in Saint Louis developed a new strategy of staging rotating exhibitions that both honor the best players in the game as well as highlighting the intersections between chess and popular culture.

Once reopened, the WCHOF adopted a collecting philosophy that reflected this exhibitions strategy and its mission to educate visitors, fans, players, and scholars by collecting, preserving, exhibiting, and interpreting the game of chess and its continuing cultural and artistic significance. After a brief hiatus in seeking new acquisitions following its opening, the WCHOF’s collection has grown by leaps and bounds.

The WCHOF accessions artifacts as varied as pop culture chess sets and chess-themed advertisements, pins and posters commemorating important competitions, and archives belonging to members of the U.S. and World Chess Halls of Fame. The institution acquires some in anticipation of upcoming exhibitions, while other donations, like that of the archive of 2014 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Jacqueline Piatigorsky, enhance or shape our exhibition program. The WCHOF’s relationship with its sister organization, the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis, also offers us a unique opportunity to collect artifacts related to elite tournaments like the Sinquefield Cup, U.S. Chess Championship, U.S. Women’s Chess Championship, and U.S. Junior Closed Chess Championship as they happen on the Saint Louis Chess Campus. Through protecting and exhibiting these artifacts, we hope to educate and inspire visitors. In this brochure, we share stories about a small selection of the artifacts on view from International Master John Donaldson, Joram Piatigorsky, 2006 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Yasser Seirawan, and staff at the WCHOF and the CCSCSL.

—Emily Allred, Assistant Curator, World Chess Hall of Fame

Joram Piatigorsky

Joram Piatigorsky is a scientist, author, and the son of 2014 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Jacqueline Piatigorsky. Along with his sister Jephta Drachman, he donated his mother’s archives, an incredible resource for American chess history, to the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) in 2014. These materials formed the basis for the WCHOF’s 2013 exhibition Jacqueline Piatigorsky: Patron, Player, Pioneer. In this excerpt from the speech Joram gave at the 2014 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame induction ceremony, he describes the role of chess in his mother’s life.

Chess, for my mother, was a love that exceeded ambition.

As for all chess players, winning was important for her, and losing was always a painful experience. But for my mother, winning had nothing to do with defeating others. It was always to prove to herself that she was worthy. Throughout my youth, before she went to play a chess tournament, she always sheepishly asked me, “It’s okay if I lose, isn’t it?”

I never heard her utter a single triumphant word when she won, which was often and with brilliance, nor did I ever hear her express a need to be recognized. My mother’s efforts in supporting chess were devoted to achieving progress despite obstacles. My mother would have been proud if she had known that she was inducted posthumously into the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, but she would have been equally surprised. She promoted chess in the United States through the Piatigorsky Cup tournaments (1963 and 1966), she formed a chess foundation to help chess players in whatever way she could, she introduced chess to kids in schools, and then to the hard of hearing. I remember her learning and practicing sign language to be able to communicate with the deaf for teaching chess.

In a nutshell, I believe that my mother’s contributions in chess serve as a model of what can be achieved by devoting one’s energy and effort to what one loves and respects.

It is also worth mentioning that my mother’s relationship with chess was a two-way street. She didn’t only give; she was also acutely aware of benefitting as well from the chess community. She felt comfortable in a chess environment and she greatly appreciated the help and friendship she received in chess from many of the chess players of her era, especially Herman Steiner and Sammy Reshevsky, from whom she learned so much. She never took anyone or anything for granted. In fact, chess was more than a game for my mother: it was a savior of sorts. Although she was fortunate to be raised under privileged conditions as a Rothschild in France, her circumstances also resulted in emotional deprivation and lack of love and understanding that everyone needs for a rich childhood, as she explained clearly in her book, Jump in the Waves (1988). It was chess that filled the void and gave her comfort.

—Joram Piatigorsky

Yasser Seirawan

Grandmaster (GM) Yasser Seirawan is a four-time U.S. Chess Champion, 2006 inductee to the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, a well-respected chess journalist and author, and a commentator for the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis’s world-class events. Seirawan has also lectured at the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) and donated an archive of materials related to his career. Here, he offers insight into a poster acquired by the WCHOF, which advertises the 1981 World Chess Championship, where Seirawan was a second for Viktor Korchnoi.

The 1981 World Championship match, in which Anatoly Karpov and Viktor Korchnoi competed, was played under a “must win six games” rule, whereby draws did not count.

Karpov won the match with six wins against two wins for his opponent Viktor Korchnoi, as well as ten draws between them. Some have argued that Merano was the “third world championship match” between these two great players. In 1974, Karpov won the Candidate’s Finals match against Korchnoi with a score of 12 1⁄2-11 1⁄2. The winner, Karpov, became the official challenger to reigning World Chess Champion Robert “Bobby” James Fischer. In 1975, Fischer forfeited the match as well as the title. So in fact, the winner of the 1974 Candidate’s Final became the world chess champion.

Karpov and Korchnoi played their first official match for the World Chess Championship in 1978 in Baguio City, Philippines. With the match tied five wins each after 31 games of play, Karpov won game 32, winning the match 6-5. Again winning a match by a single game. Merano 1981 was the last time that Karpov and Korchnoi fought for the title. In 1984, Karpov had a new challenger, Garry Kasparov.

For me, the match in Merano was an unfair contest. On the eve of the match, Igor, the son of the famous defector Viktor Korchnoi, was arrested for failure to be conscripted into the army. At the time, Igor had applied to emigrate from the Soviet Union to join his father in Switzerland. It was a Catch 22. If Igor had gone to the army he would never have been allowed to emigrate as he would then know “State secrets.” The arrest of his son was a great emotional blow for Viktor, and he played poorly from start to finish. Igor would serve two and a half years of hard labor in a prison camp before finally being allowed to emigrate.

—Yasser Seirawan

John Donaldson

International Master (IM) John Donaldson has served as director of the Mechanics’ Institute Library and Chess Room in San Francisco, California, since 1998. He worked for Inside Chess magazine (1988-2000) and authored over 30 books on chess. He has captained the U.S. national chess team on 19 occasions, most recently during the 2016 Chess Olympiad, where the Americans won team gold, the first since 1976. Donaldson is also a frequent donor of artifacts, and a writer and researcher for exhibitions at the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF). Here he offers a remembrance of 2003 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Walter Browne, whose archive was donated to the WCHOF by Raquel Browne in 2015.

Chess players who grew up in the 1960s and 1970s remember Walter Browne as a ferocious competitor.

Watching the six-time U.S. chess champion play in his habitual time pressure, with his whole body shaking, one immediately realized this was a competitor who consistently gave his all. Walter’s endless quest to play the perfect game may not have been the most practical approach, but it led to many beautiful and memorable victories that connoisseurs of great chess will appreciate as long as the game is played.

This memory of Walter as the uncompromising “Energizer Bunny” of chess is an accurate one but it does not come close to conveying the many contributions he made to the game, several of which are represented by artifacts from his archive on view in Open Files: Celebrating 5 Years of Collecting. Witness the two chess clocks, one a very early digital model, which evoke Browne’s passion for blitz chess, evidenced by his founding of the World Blitz Chess Association (1988) and the magazine Blitz Chess (1988-2003). Walter advertised the leather pocket chess set from Argentina, a favorite of fellow U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Bobby Fischer, in the tournament bulletin service he ran in the 1970s and early 1980s. The pieces in the Hollendonner Chess Set Browne endorsed evoke the shapes of the pieces used in the variant Finesse Chess that he championed the last decade of his life. Walter loved all aspects of chess and few can match his passion and intensity for the game.

—IM John Donaldson

Tony Rich

Tony Rich has served as the executive director of the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis (CCSCSL) since 2008. Rich is recognized by U.S. Chess as a Senior Tournament Director and has been licensed as an International Arbiter by FIDE, one of only 22 FIDE International Organizers in the nation. In addition to his role as the Chief Arbiter in 2015, Rich has served as either Chief or Deputy Arbiter in more than 10 national championship events since 2009 and organized dozens of elite matches, exhibitions, and other international events.

We all know that chess goes way back, earlier than actual knights in armor and kings on the battlefield.

What you may not know is that Saint Louis has been at the forefront since the earliest days of modern chess. In fact, the “Gateway to the West” played host to a critical portion of the rst World Chess Championship match in 1886. Saint Louis also hosted the U.S. Open Chess Championship in 1904, 1929, 1941, and 1960.

Before the Chess Club and Scholastic Center’s 2008 opening, it would be easy to assume Saint Louis had already seen its chess heyday. However, this event initiated the next chapter of chess in Saint Louis. The following year, the Club organized and hosted our first U.S. Chess Championship, boldly announcing that Saint Louis was where to look for the future of chess. And look they did; chess players, organizers and fans flocked to Saint Louis, where the CCSCSL hosted the U.S. Chess Championship, U.S. Women’s Chess Championship, and U.S. Junior Closed Chess Championship, in the process becoming known as the preeminent club in the nation. Three years later, the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) opened its doors on a beautiful autumn day.

The WCHOF brought a new voice to the conversation. If the club focused on how to play chess, the Hall of Fame demonstrated why we play. Through its innovative exhibitions and creative programming over the last ve years, the WCHOF has introduced many new players to the game, brought others back in the fold, and helped chess become an integral part of mainstream culture.

The CCSCSL and WCHOF work very closely together to produce something greater than the sum of their parts. Whether curating mini-exhibitions at the Club or hosting the Sinquefield Cup (a tournament named for the generous founders of our organization, Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinque eld) closing ceremony at the WCHOF, the two organizations seamlessly complement each other. In order to bring those important artifacts and memorabilia to the masses, the WCHOF continually collects, preserves, and memorializes pieces of Saint Louis chess history through their permanent collection and loaned items. Thanks to the team of mission-oriented professionals at the WCHOF, I am confident that our great-great-great-grandchildren will have the opportunity to enjoy the history we are creating today.

—Tony Rich

Emily Allred

Emily Allred is the Assistant Curator of the World Chess Hall of Fame. She has worked at the institution since 2013 and has curated or co-curated a number of exhibitions including Prized and Played: Highlights from the Jon Crumiller Collection; Jacqueline Piatigorsky: Patron, Player, Pioneer; A Memorable Life: A Glimpse into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer; Living Like Kings: The Unexpected Collision of Chess and Hip Hop; Battle on the Board: Chess during World War II; and Her Turn: Revolutionary Women of Chess.

While the World Chess Hall of Fame’s name evokes one of our major tasks—honoring the game’s most memorable—our mission is also more broad, guiding us to honor the game’s cultural and artistic significance.

Our collection of chess sets uniquely embodies this goal. Familiar tournament style sets like the House of Staunton’s Marshall Series Staunton Chess Set, named for 1986 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Frank Marshall, take their place in our holdings next to colorful chess sets inspired by popular culture, like the Hello Kitty Chess Game. Though they may differ in form and material, they all serve to tell stories about chess, both on an international and a personal level.

Named for and popularized by 2016 World Chess Hall of Fame inductee Howard Staunton (1810-1874), the Staunton-style of chess set is now the standard for tournament play. The set for the 2002 exhibition match between World Chess Champions Anatoly Karpov and Garry Kasparov on view in Open Files takes influence from this famous style, which emphasized easily recognizable pieces that could be used by players around the world. The set is significant because the two players used it in the only match in which Karpov defeated Kasparov.

Other sets in the World Chess Hall of Fame’s (WCHOF) collection include unique interpretations of these classic forms. Herman Ohme’s sleek mid-century chess set evokes the aesthetics of the era of its creation, while Okuma America Corporation’s industrial chess set made from aluminum and bronze used the challenge of creating the pieces’ forms as a means of showcasing the abilities of its machining tools. The Wood and Masonry Chess Set donated to the WCHOF by Bud and Marlene Dale and tells one story about how chess brings people together. Gerald Hagel, the president of Ackerman Johnson Fastening Systems, Inc, gave sets like this one as Christmas gifts to the company’s sales representatives like Bud Dale. These sets make up only a small portion of the WCHOF’s chess set collection; nevertheless, they exemplify the diversity and creativity of the WCHOF’s artifacts.

—Emily Allred

Artifacts Featured in the Exhibition: Promotional Photography

Photographer unknown

Good Knight!

1972

10 1∕8 x 8 in.

Press photograph

© United Press International

Published as U.S. and World Chess Hall of Fame inductee Bobby Fischer fought for the title of World Chess Champion, this photo pictures Italian actress Liliana Chiari as a living chessboard. Fischer’s rise to chess dominance influenced popular culture not only in the United States, but also around the world, and the caption for this photo noted that the impact of his match against Boris Spassky was being felt in Rome, where this picture was taken.

Photographer unknown

Tie-Die Hits Bottom

1971

10 1∕8 x 8 1∕16 in.

Press photograph

© United Press International

To promote Neolite shoe soles, a product manufactured by the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, this photograph pictures a fashionable young woman playing chess. Though the oversize pieces she plays with are a familiar tournament chess set style, the accompanying board, a checkered black and white shag rug, evokes hippie culture, as do the tie-dyed soles of her shoes. In both the past and the present, chess is often used as a symbol of making strategic moves in purchasing decisions.

Photographer unknown

Chess Anyone?

1967

10 1∕8 x 7 15∕16 in.

Press photograph

© United Press International

A woman with a fashionable beehive hairstyle gazes through a variety of drill bits arranged to resemble a chess set. The image promoted the products of the Winslow Division of Omark Industries, Inc. The “set” bears similarities to the Wood and Masonry Chess Set also on view in this gallery. In both, humble industrial materials are transformed into chess sets, illustrating that with a little ingenuity, a chess set can be created from common objects.

Artifacts Featured in the Exhibition: Postcards

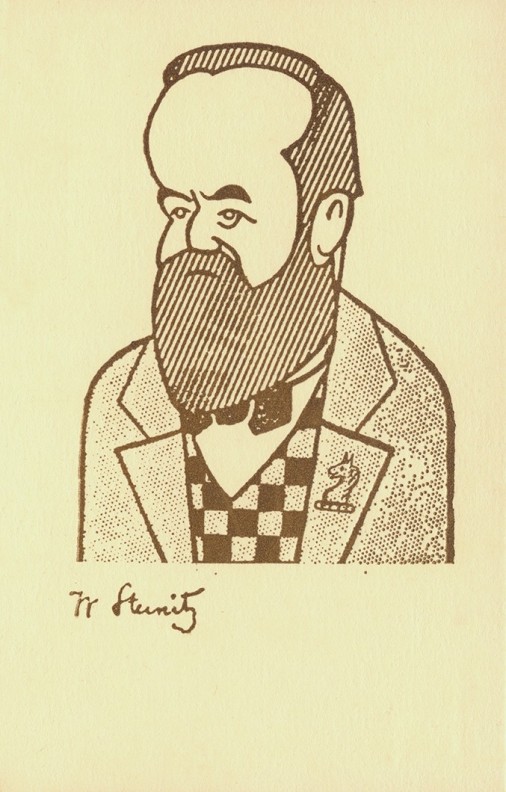

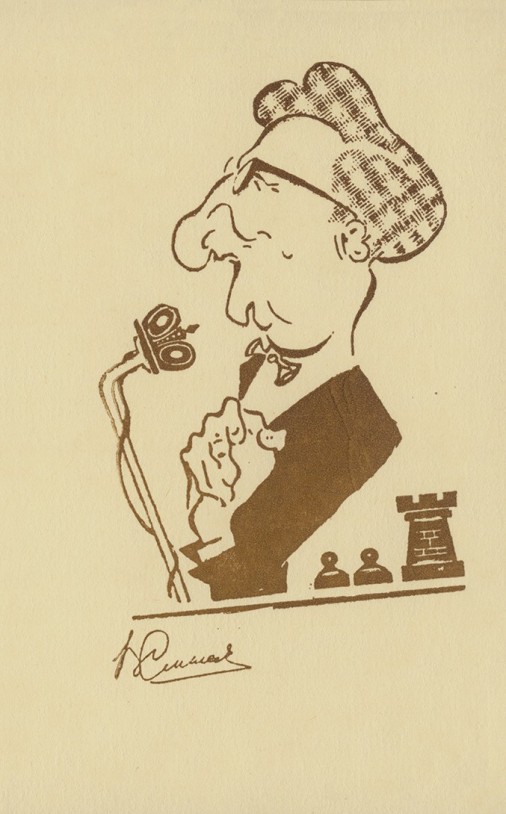

Colorfully caricatured here are many of the most famous players of the twentieth century. This postcard series features winners of the World Chess Championship. Saint Louis hosted a portion of the first Championship, which was won by Wilhelm Steinitz, one of the figures depicted in this series. Though the World Chess Hall of Fame collects more formal portraits and photographs from chess events (like the ones on view in this gallery), it also acquires fun images like these that speak to how chess is viewed in popular culture.

Wilhelm Steinitz (1836-1900), from World Chess Champions 1886-1986 Postcard Series

c. 1989

5 7∕8 x 3 ¾ in.

Postcard

Born in Austria, William Steinitz (World Chess Champion, 1886-1894) was one of the most influential players, writers, and theoreticians in the history of the game. He became the first official World Champion in 1886, following victory in a match against Johannes Zukertort played in New York, Saint Louis, and New Orleans. His early observations and theories are still quoted as the foundations and basic principles of chess mastery.

Boris Spassky (b. 1937), from World Chess Champions 1886-1986 Postcard Series

c. 1989

5 7∕8 x 3 ¾ in.

Postcard

Boris Spassky (World Chess Champion, 1969-1972) is most famous for his loss of the World Championship crown to Bobby Fischer at Reykjavik in 1972, in the most famous chess match of all time. Despite this dubious honor, Spassky has been considered one of the world’s best players for decades. World Junior Champion and a world title candidate by age 18, Spassky showed an early, hyper-aggressive brilliance that matured into seamless universality. Spassky’s influence reached even to Hollywood, as his stunning 15th move against David Bronstein was immortalized in the film classic From Russia with Love.

Dr. Emanuel Lasker (1868-1941), from World Chess Champions 1886-1986 Postcard Series

c. 1989

6 x 3 ¾ in.

Postcard

The second world champion from 1894 to 1921, Emanuel Lasker held the official chess crown for 27 years, longer than anyone else in history. Incorporating psychology into his play, Lasker is considered by modern analysts to have had a style ahead of his time, as many of his moves that his contemporaries considered mysterious are now commonplace. Despite playing before the use of statistical rankings, modern analysis regularly places Lasker in the top ten players of all time.

Dr. Mikhail Botvinnik (1911-1995), from World Chess Champions 1886-1986 Postcard Series

c. 1989

5 7∕8 x 3 ¾ in.

Postcard

After dominating tournament play through most of the 1940s, Mikhail Botvinnik (World Chess Champion, 1948-1963) captured the 6th World Championship title in 1948. Botvinnik’s intense training regimen distinguished him from his peers. He advocated logic, extensive theoretical research, and a strong degree of both physical and mental discipline. His scientific style emphasized whole systems of play that extended from the opening to the endgame. Dubbed “Patriarch of the Soviet Chess School,” he mentored and trained numerous young Soviet players, including a young Garry Kasparov.

Vasily Smyslov (1921-2010), from World Chess Champions 1886-1986 Postcard Series

c. 1989

5 7∕8 x 3 ¾ in.

Postcard

Chess was simply a hobby for young Vasily Smyslov (World Chess Champion, 1957-1958) until age 14, when appearances by José Capablanca and Emanuel Lasker in Moscow inspired a lifelong passion. Smyslov first began to attract international attention when he defeated Samuel Reshevsky twice in the famous U.S.-USSR radio match of 1945. Smyslov holds an all time record of 17 Olympiad medals, ten gold medals at five European Team Championships, and the inaugural World Senior Chess Championship title in 1991. An opera singer, Smyslov sought harmony in his chess game, ensuring that all his pieces moved in cooperation with one another.

José Raúl Capablanca (1888-1942), from World Chess Champions 1886-1986 Postcard Series

c. 1989

5 7∕8 x 3 ¾ in.

Postcard

Nicknamed “The Human Chess Machine,” José Raúl Capablanca (World Chess Champion, 1921-1927) was born in Havana, Cuba. A true prodigy, he learned chess at age four. Perhaps the greatest natural player ever, “Capa” often defeated world-famous opponents with apparent ease. He was a master of positional play, but could also play great tactical chess. Handsome and elegant, he is one of the most beloved and admired champions.

Mikhail Tal (1936-1992), from World Chess Champions 1886-1986 Postcard Series

c. 1989

5 7∕8 x 3 ¾ in.

Postcard

In 1960, Mikhail Tal became the youngest World Chess Champion at that time. He was the fiercest attacking player ever to hold the title. Known as “the Magician from Riga,” many players were inspired by Tal’s highly creative and explosive style. Tal holds the record for the first and second longest unbeaten streaks in the history of competitive chess, and his legacy lives on in his numerous writings and in the Mikhail Tal Memorial Tournament, which features many of the world’s strongest players.

Tigran Petrosian (1929-1984), from World Chess Champions 1886-1986 Postcard Series

c. 1989

5 7∕8 x 3 ¾ in.

Postcard

As winner of the 9th World Championship in 1963, Tigran Petrosian (World Chess Champion, 1963-1969) ended the Botvinnik era, which had lasted 15 years. Impoverished and orphaned during World War II, the young Petrosian began to develop his chess skills through reading and training at the Tiflis Palace of Pioneers, where he developed a solid, scientific style of play under Archil Ebralidze. Petrosian seldom attacked pieces directly, preferring slow, subtle maneuvering, a style that earned him the nickname “Iron Tiger” and make him what many considered the hardest player to beat in the history of chess.

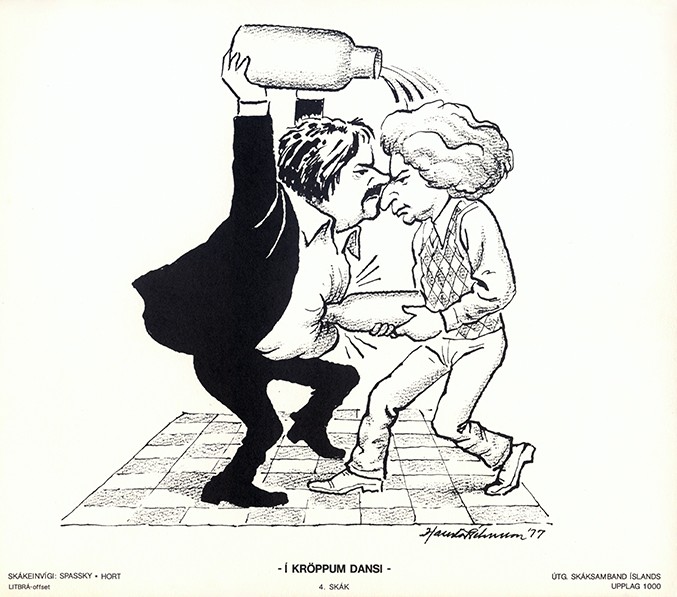

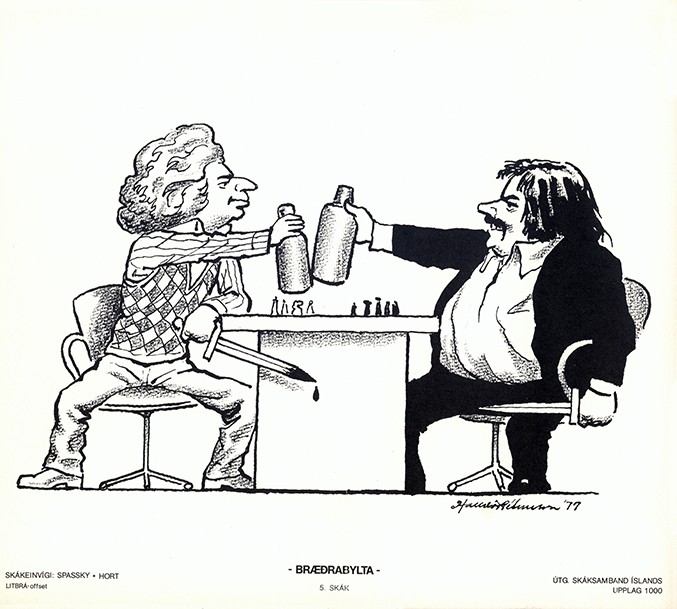

While photographer Harry Benson captured some of the most memorable photographs of the 1972 World Chess Championship Match between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky, Halldór Pétursson created iconic cartoons depicting the drama-filled and sometimes surreal events of the match. Presented in Open Files are four of these images. They appeared on souvenir items like postcards and in magazines and newspapers in Iceland and around the world.

Halldór Pétursson

Iceland – NR. 6

1972

5 7∕8 x 8 11∕16 in.

Postcard

© Halldór Pétursson

In this humorous illustration, Fischer appears to control anthropomorphic chess pieces with the power of his mind. Game 6 of the match later became famous for being one of the most beautiful games ever played. It was so impressive that even Spassky applauded Fischer after his victory.

Halldór Pétursson

Iceland – NR. 14

1972

5 7∕8 x 8 11∕16 in.

Postcard

© Halldór Pétursson

Spassky and Fischer stoically shake hands in the midst of a chaotic scene in this illustration that captures two of the most humorous controversies of the 1972 World Chess Championship. As a result of Soviet accusations that Fischer might be affecting Spassky’s behavior through “chemical substances if not by electronic means,” police officers and scientists in Reykjavik fieldstripped Spassky’s chair and x-rayed it to ensure that Fischer was receiving no unfair advantages. The Soviets also demanded that a light above the playing area be taken apart to confirm that no electronic devices were in it that could influence Spassky’s play. The only materials found in the light were two dead flies.

Halldór Pétursson

Iceland – NR. 2

1972

5 7∕8 x 8 11∕16 in.

Postcard

© Halldór Pétursson

In this postcard, which represents the second round of the match, Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer are represented as jousting knights. Fischer wears a cowboy hat, perhaps a reference to his American heritage, while the reigning champion, Spassky, wears a crown. Fischer charges away from his opponent, while worried onlookers point in the direction of Spassky. The illustration refers to Fischer’s forfeit to Spassky following organizers’ failure to remove cameras from the hall where the tournament was held.

Halldór Pétursson

Iceland – NR. 18

1972

5 7∕8 x 8 11∕16 in.

Postcard

© Halldór Pétursson

A victorious Fischer, one foot atop a pile of money, crowns himself king following the conclusion of the 1972 World Chess Championship tournament. He and Spassky are wearing viking style costumes, a reference to the “viking buffet” held by the Icelandic Chess Federation in Fisher’s honor. An Associated Press story about the banquet noted that Fischer spent much of the event analyzing the final game with Spassky, and that “Viking blood” (red wine) was served in horns.

Halldór Pétursson

In a Steep Dance from the Chess Duel: Spassky—Hort Postcard Series

1977

7 ¼ x 8 ½ in.

Gift of Raquel Browne

Halldór Pétursson

Brothers in Arms from the Chess Duel: Spassky—Hort Postcard Series

1977

7 ¼ x 8 ½ in.

Gift of Raquel Browne

Halldór Pétursson

A War of Nerves from the Chess Duel: Spassky—Hort Postcard Series

1977

7 ¼ x 8 ½ in.

Gift of Raquel Browne

Halldór Pétursson

A Fight of Great Importance from the Chess Duel: Spassky—Hort Postcard Series

1977

7 ¼ x 8 ½ in.

Gift of Raquel Browne

Halldór Pétursson created these postcards as part of a series celebrating the 1977 Candidates’ semifinal Match between Boris Spassky and Vlastimil Hort, which was held in Reykjavik, Iceland. Spassky had only narrowly been able to enter the competition, which helped determine who would challenge Anatoly Karpov for the World Chess Championship. Bobby Fischer declined to participate in the competition and Spassky took his place. Spassky earned a narrow victory over Hort following a two-week break in their match due to Spassky having a health emergency and receiving an appendectomy.

Hort gained an advantage over Spassky in the final game, but lost heartbreakingly after forgetting about time control as he was entranced by the thought of victory. Though Spassky was victorious in this match, Viktor Korchnoi ultimately earned the chance to challenge Anatoly Karpov for the title of World Chess Champion. Perhaps because the match lacked the drama of the Bobby Fischer-Boris Spassky match depicted in the other postcards, these illustration seem to be more generic scenes of chess as a battle.

Artifacts Featured in the Exhibition: The Piatigorsky Collection

These artifacts are part of a generous gift of the archives of Jacqueline Piatigorsky from her daughter, Jephta Drachman, and her son, Joram Piatigorsky. Through her sponsorship of the legendary Piatigorsky Cup tournaments, creation of the Piatigorsky Foundation, and her representation of the United States in the rst Women’s Chess Olympiad in 1957, Jacqueline Piatigorsky had a profound influence on twentieth-century American chess. Jacqueline’s legacy impacted chess on the local, national, and international levels. She organized two of the strongest chess tournaments held on American soil, the Piatigorsky Cups (1963, 1966). The artifacts in this case pertain to Piatigorsky’s support of the career of American chess champion Bobby Fischer.

Manufacturer of Cup: Tiffany & Co.

Piatigorsky Cup Trophy

1963

13 x 30 x 19 1⁄2 in.

Trophy

Gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

The well-known jewelry and silverware manufacturer Tiffany & Co. manufactured the gleaming sterling silver two-handled vessel, or “love cup” at the center the Piatigorsky Cup trophy. Tiffany & Co. produced the Nassau Cup, a trophy for a sailing competition, in the same pattern. The Cup is anked by two silver-plated Régence-style chess pieces, a king and a queen. Régence-style chess sets originated in France, where Jacqueline was born. This trophy was intended for display during the competition. A reduced-size version of the Cup was presented to Boris Spassky (World Chess Hall of Fame, 2003) after his victory in the 1966 competition. As the Piatigorsky Cup was originally planned to be held every two or three years, the front of the trophy has space for the names of future winners. However, Jacqueline stopped organizing the competitions after the 1966 event due to the immense amount of effort required to gain the participation of some of the players.

Postcard from Ed Edmondson to Jacqueline Piatigorsky

Palma de Mallorca, Spain, November 14, 1970

6 1∕8 x 4 1∕8 in.

Postcard

Gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

United States Chess Federation President Ed Edmondson (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 1995) wrote this letter to Jacqueline Piatigorsky while serving as manager to Bobby Fischer (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 1986; World Chess Hall of Fame, 2001) in the 1970 Palma de Mallorca Interzonal Tournament. The competition served as a part of the World Chess Championship qualifying cycle, and Jacqueline’s philanthropic chess organization was nancially supporting Fischer’s run. In the letter, Edmondson mentions one of the games being postponed due to a concert, but that “all [is] going reasonably well so far.” Fischer had dropped out of the previous Interzonal Tournament in 1967 due to disagreements with organizers, possibly contributing to Edmondson’s cautious tone in the letter. However he won the 1970 Interzonal, taking another step forward toward his future World Chess Championship match against Boris Spassky.

Postcard from Larry Evans to Jacqueline Piatigorsky

November 15, 1970

6 1∕8 x 4 1∕8 in.

Postcard

Gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

Jacqueline Piatigorsky (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 2013) and Larry Evans (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 1994), were longtime friends by the time Evans wrote this letter to her. The two had possibly first met at a 1951 dinner honoring Evans’ victory in that year’s U.S. Chess Championship, a photograph of which is on view in this gallery. Here, Evans, who later served as a “second” for famed American chess champion Bobby Fischer (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame 1986; World Chess Hall of Fame, 2001) in the 1971 Candidates Matches writes to Jacqueline during the progress of the 1970 Interzonal Tournament. He suggests that following Fischer’s imminent victory in the competition, one of the matches might be held in Los Angeles, where Piatigorsky had previously organized the prestigious Piatigorsky Cup tournaments.

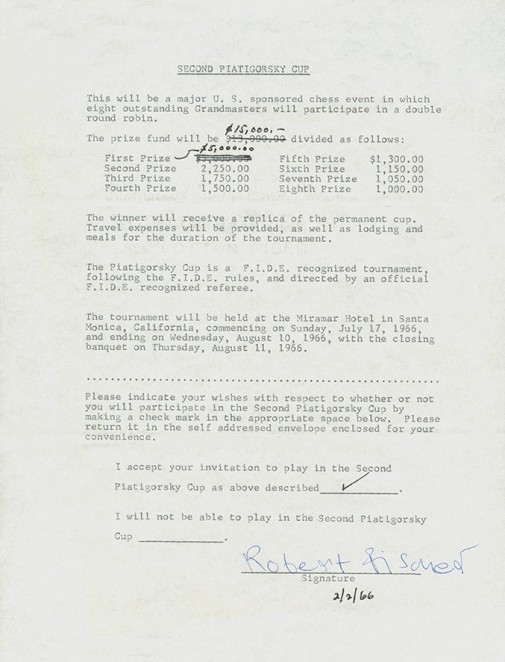

Bobby Fischer’s Contract from the Second Piatigorsky Cup

February 2, 1966

11 x 8 1⁄2 in.

Document

Gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

In this contract, Bobby Fischer accepts an invitation to play in the second Piatigorsky Cup tournament. Jacqueline Piatigorsky, the organizer of the tournament, negotiated extensively with the chess star to ensure his participation. Fischer eventually took second in the tournament, behind his rival Boris Spassky. The Piatigorsky Cups (1963, 1966) were the strongest chess tournaments held in the United States until the creation of the Sinquefield Cups, which are now staged annually at the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis.

Letter to Jacqueline Piatigorsky from Bobby Fischer

1966

11 x 8 1⁄2 in.

Document

Gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

In this letter, which accompanied his analysis of a game against Miguel Najdorf that he played in the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, Bobby Fischer writes of his understanding of the publishing agreement for the landmark tournament book for the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup. Unlike his competitors in the tournament, Fischer only annotated one game for the book. He would eventually include this confrontation in his famous book My 60 Memorable Games. The tournament proved important for Fischer’s career as it helped him gain con dence that would be crucial for his run for the 1972 World Chess Championship.

Artifacts Featured in the Exhibition: Advertisements

Often associated with intelligence, sophistication, inspiration, strategy, and success, chess effortlessly fits into marketing campaigns selling myriad products. There is something so unique about the game of chess—its far-reaching popularity and easily recognizable concept makes it the ideal tool to promote merchandise ranging from magazine subscriptions to skis. Since the game and terms associated with it are so ingrained into society, one does not have to be a skilled player to understand intricate details and see the connections, making it a perfect metaphor for when a company wants you to make the right “move” to buy its product. Since many chess terms and phrases, such as checkmate, pawn, and opening move, are now a part of the English lexicon, the game’s inclusion in advertisements captures a certain air of class and logic, touching on aspects that marketers believe people see, or want to see, in themselves.

Woman’s Day Magazine Advertisement

1952

11 5∕8 x 16 3∕8 in.

Print advertisement

© Woman’s Day Magazine

In this advertisement for Woman’s Day magazine, marketers celebrate the purchasing power of the queen. In the image, an anthropomorphized chess queen reads an issue of her favorite magazine. Woman’s Day originated as a menu sheet in 1931 and later became a full magazine in 1937.

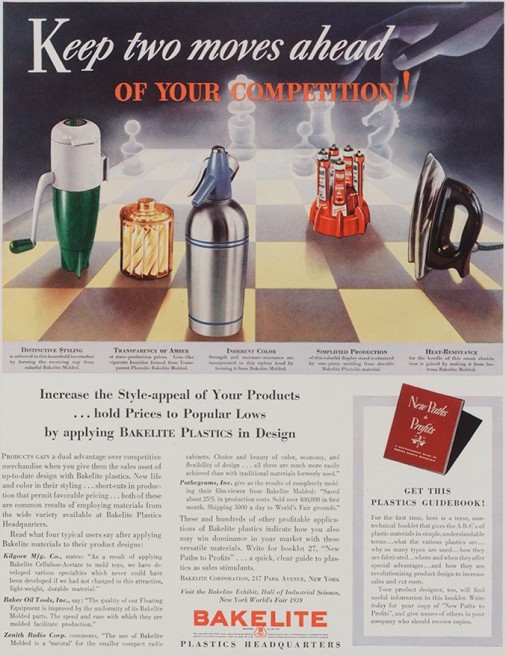

Bakelite Corp. Advertisement

1939

13 7∕8 x 10 ½ in.

Print advertisement

Urging consumers to “keep two moves ahead” of their competition, this ad for Bakelite pictures household appliances as pieces on a chessboard. Each of the “pieces” showcases a quality of Bakelite, an early type of plastic used to create a number of products, including chess sets. The appliances oppose a ghostly set of chess pieces, whose forms are inspired by Régence chess sets. These French sets are named after the Café de la Régence in Paris, where many skilled players and intellectuals congregated.

Hart Skis Advertisement

1972

10 11∕16 x 8 3∕16 in.

Print advertisement

Hart Skis™”

This print advertisement, which sports a skiing anthropomorphic chess set, is an instance of a company using the idea of chess to promote the quality of their product. Urging viewers to join the “Hart Skis Chess Team,” these advertisements were published in industry magazines in 1973. They were inspired by the American Bobby Fischer’s victory in the 1972 World Chess Championship. The news of his victory was plastered on newspapers across the country and chess references often appeared in pop culture. Hoping to use this sudden interest in the game to bolster sales, the Hart company named its new line of skis after chess pieces. As the advertisement states, each piece also demonstrated a skill level, the king for the professional and the pawn for the beginner.

Artifacts Featured in the Exhibition: Pop Culture Sets

The television, movie, and video game -inspired chess sets in the World Chess Hall of Fame’s (WCHOF) collection provide a perfect complement to its holdings of antique, one-of-a-kind sets. Made from humble materials like plastic, the sets are mass-produced and intended for children or enthusiasts of the subjects they depict.

South Park Collector Chess Game

2004

King: 3 5⁄16 in.

Chess set

The stars of South Park are led by Chef, the character famously voiced by soul singer Isaac Hayes, as the king, and Big Gay Al as the queen in this set inspired by the long-running show. In August 1997, the show premiered on Comedy Central, and on September 14, 2016, its 20th season began. The animated sitcom takes place in the fictional town of South Park and follows the adventures of four children— Stan (rook), Cartman (knight), Kyle (bishop), and Kenny (pawn). The satirical show has attracted both controversy and acclaim in its years on the air, earning 5 Emmys.

Gaya Entertainment Gmblt

Sonic the Hedgehog 3D Chess

Date unknown

King size: 2 7⁄8 in.

Chess set

© Sega

In this set, characters from the 25-year-old video game Sonic the Hedgehog become pieces in one of the world’s oldest games. Sonic, the titular blue hedgehog, debuted in 1991, battling against the game’s antagonist Doctor Ivo “Eggman” Robotnik. Sonic was positioned as the Sega Company’s response to the Nintendo Company’s Mario. Here, he is anked by other characters from the franchise, who include Knuckles the echidna, Miles or “Tails” the fox, and Amy Rose the hedgehog.

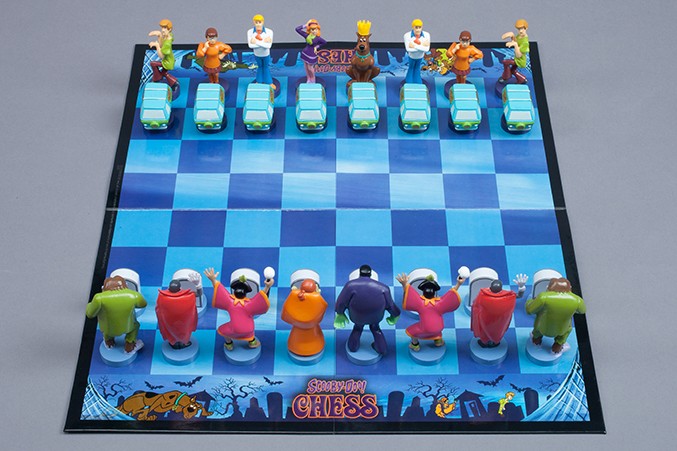

Friendly Games Inc.

Scooby-Doo! Chess Set

Date unknown

King size: Scooby Doo 2 3⁄4 in.; Frankenstein 3 1⁄8 in.

Chess set

© Hanna Barbera Productions Inc.

Great Dane Scooby-Doo reigns as king in this chess set inspired by the television show Scooby-Doo, Where Are You!. In the show, Scooby and his friends, Shaggy, Velma, Fred, and Daphne, solve mysteries featuring supernatural suspects, who were revealed to be human at the end of the episode. Villains from the show oppose the plucky investigators in this set. Hanna-Barbera Productions produced Scooby-Doo, Where Are You!, which aired as a Saturday morning cartoon from 1969-70, but the show has been revived many times since, with one incarnation featuring a character voiced by Saint Louis native Vincent Price (1911-1993).

Character Games

Limited Looney Tunes Chess Set

1999

King size: Elmer Fudd 3 1⁄8 in.; Taz 3 in.

Chess set

© Warner Bros.

In this set, many characters from Looney Tunes, take their mischievous antics to the arena of the chessboard. Produced by Warner Brothers beginning in 1930, Looney Tunes set the adventures of a humorous group of cartoon animals to music. Unlike in some of the other sets inspired by popular culture, this set does not simply set characters of virtue against their antagonists. Here, one side has Elmer Fudd as king, Granny as queen, Roadrunner as bishop, Pepé Le Pew as knight, Foghorn Leghorn as rook, and Speedy Gonzales as the pawns. Opposing them is a team led by Taz as king, Tasmanian She-Devil as queen, Wile E. Coyote as bishop, Sylvester the Cat as knight, Gossamer/Rudolph as rook, and Marvin the Martian as the pawns.

Cardinal Industries Inc.

The Simpsons Chess Set

2000

King size: 3 1⁄2 in.

Chess set

© 20th Century Fox

USAOPOLY

Peanuts Chess Set

Date unknown

King size: 2 13⁄16 in.

Chess set

© United Feature Syndicate Inc.

Created by cartoonist Charles Schulz, the comic strip Peanuts ran in newspapers for nearly 50 years from October 2, 1950, to its last on February 13, 2000. Peanuts followed the adventures of Charlie Brown and the “Peanuts gang.” This set alludes to a few of the famous characters’ attributes. Charlie Brown is dressed in baseball gear, a reference to his management of a baseball team that included his friend Lucy and that had a lopsided losing record. Linus holds his security blanket while Sally clutches a valentine that says “sweet baboo,” her nickname for her crush, Linus.

Sababa Toys

Sanrio Hello Kitty Chess Game

2004

King size: 2 in.

Chess set

© 1976, 2004 Sanrio Co., LTD.

Made in honor of Hello Kitty’s 30th anniversary, this set features the titular character and her friends as adorable pieces, complete with rocking horse knights that actually wobble. As part of the anniversary celebration, Hello Kitty partnered with the United Nation’s Children’s Fund (UNICEF) to share profits from a line of anniversary products to benefit girls’ education programs around the world and to teach about gender discrimination in education. Designer Yuko Yamaguchi created Hello Kitty in 1974. The character soon appeared on a wide variety of consumer prodects, but her popularity exploded in the 1980s, when Sanrio made a concerted effort to adapt her appearance to market to older children.

Wood Expressions Inc.

The Flintstones 3-D Chess

1993

King size: Fred 3 3⁄16 in.; Barney 2 3⁄4 in.

Chess set

© Hanna Barbera Productions Inc.

The Flintstones, the first animated primetime sitcom, premiered on September 30, 1960. Though set in a fictionalized version of the prehistoric era where humans and dinosaurs coexisted, the show included references to contemporary culture. The Flintstone and Rubble homes featured the “latest” appliances, included foot-pedaled cars, represented as rooks in this set. In the other pieces, Fred, Wilma, and Pebbles Flintstone, along with their pet Dino, oppose their neighbors, the Rubble family.

Sababa Toys

Sesame Street Deluxe Collector’s Chess Set

2004

King size: 3 in.

Chess set

© Sesame Workshop

Created in commemoration of Sesame Street’s 35th season, this chess set features familiar characters from the children’s television show. Sesame Street premiered on November 10, 1969, and aspired to blend education and entertainment. Many of the show’s most beloved characters are included in this set, each wearing humorous versions of costumes from a medieval court. The pawns are lampposts with signs pointing the way to Sesame Street.

USAOPOLY

Disney Chess Collector’s Edition

2004

King size: Beast 2 13/16 in.; Captain Hook 4 in.

Chess set

© Disney Enterprises

Brave heroes take on dastardly villains in this set containing characters from animated films produced by the Disney company. Many of them are from popular films released or re-released during the 1990s. In this set, blue is represented by the heroes, with Beast as king, Belle as queen, Genie as bishop, Hercules as knight, Simba as rook, and Lucky as pawns. On the purple side are the villains, with Captain Hook as king, Cruella de Vil as queen, Jafar as bishop, Hades as knight, Scar as rook, and Ed the Hyena as the pawns.

Artifacts Featured in the Exhibition: Chess Pins

Pin from the 1983 Jurmala, Latvia, International Chess Tournament

1983

1 15∕16 x 7∕8 in.

Pin

Gift of John Donaldson

Pin from the 1983 Jurmala, Latvia, International Chess Tournament

1983

1 ¼ in. diameter

Pin

Gift of John Donaldson

This pair of pins, one blue and white, sporting a blue and white knight with a flowing mane, and the other depicting a rook with a sailboat, commemorate the 1983 International Chess Championship held in Jurmala, Latvia. The tournament included 14 competitors who collectively played 91 games over 13 rounds. The players were primarily from the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe and included Grandmaster Oleg Romanishin, who won the event with 11 points and Mikhail Tal who tied for 5th with 6.5 points.

Pin from the 1985 Moscow, Russia, World Chess Championship

1985

¾ x 13∕16 in.

Pin

Pin from the 1984-1985 Moscow, Russia, World Chess Championship

1984-1985

11∕16 x 5∕8 in.

Pin

This pair of pins celebrates the beginning of one of the best-known rivalries in the arena of the World Chess Championship. Anatoly Karpov and Garry Kasparov fought two World Chess Championship matches in 1984 and 1985. World Chess Federation President Florencio Campomanes stopped the first match after after 5 months and 48 games of play, with neither player having won the required six games (draws not counting). In the 1985 rematch, Kasparov triumphed over his competitor.

Pin from the 2014 Tromsø, Norway, Chess Olympiad

2014

9∕16 in. sq.

Pin

Gift of John Donaldson

These five overlapping white lines on a multi-hued blue background create a number of symbols that are both significant to the game of chess and to the 2014 Chess Olympiad’s host country, Norway. To create the logo for the event, high-ranking players were asked to create abstract interpretations of their chess games. This organization of lines was chosen because when broken apart it also forms symbols of Northern Norway. These include the Arctic Cathedral, Tromso Bridge, Olympic Torch, surrounding mountains, waves from its surrounding ocean, and Lavvu (lávut), a temporary cone shaped shelter built by the Sami people during the months when they are traveling with their herds.

Pin from the 2014 Tromsø, Norway, Chess Olympiad

2014

15∕16 x 15∕16 in.

Pin

Gift of John Donaldson

This pin represents the second and final symbol for the 2014 Tromso, Norway, Chess Olympiad, a biannual international chess tournament. Organizers decided to use the official olympic colors to replace the blue and white of the previous symbol. This decision was made because these colors symbolize the colors of the flags of the competing countries. The symbol typically includes a white background that is missing from this pin.

Pin from the 1991 Philadelphia, World Open

1991

1 in. diameter

Pin

Gift of John Donaldson

A knight in front of a chessboard is pictured on this enamel pin, which celebrates the 1991 World Open. Gata Kamsky (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 2016) won the tournament. The same year he won the first of his 5 U.S. chess championship titles.

Pin from the 1987 Linares, Spain, Candidates Tournament

1987

13∕16 x 13∕16 in.

Pin

Gift of John Donaldson

The small Spanish town of Linares was the host for a series of international tournaments held between the late 1970s and 2010. These events were normally the strongest tournament of the year with Garry Kasparov competing regularly. In 1987 the tournament was not held and instead Linares hosted the Final Candidates Match between Anatoly Karpov and Andrei Sokolov to determine Garry Kasparov’s challenger. This pin commemorates that match.

Pin Commemorating Anatoly Karpov as World Chess Champion Soviet Union

N.D.

1 ¾ x 1 3∕8 in.

Pin

This pin, depicting Anatoly Karpov in profile, was made to celebrate his world chess champion title, which is stated in Russian at the bottom of the pin. Karpov held the title of world chess champion for a total of 16 years, first receiving it in 1975 when Bobby Fischer refused to defend his title.

Pin from the 1975 Riga, Latvia, Spartakiad Russia

1975

1 ½ in. sq.

Pin

Gift of John Donaldson

This commemorative pin is from the chess team competition held as part of the 6th U.S.S.R. Spartakiad in Riga, Latvia, in 1975. The Soviet Spartakiads, which started in 1956, featured thousands of competitors from many different sports and were held regularly until the collapse of the Soviet Union. The chess portion of the competition pitted the various Soviet Republics against each other and featured the very best male, female, and junior players. The 1975 event included such stars as Anatoly Karpov, Tigran Petrosian, and Mikhail Tal for the men, and Nona Gaprindashvili, Valentina Kozlovskaya, and Irina Levitina for the women.

Pin from the 1984, Vilnius, Lithuania, Final Candidates Match

1984

Diameter: 1 1∕8 in.

Length: 1 ½ in.

Pin

Gift of John Donaldson

This pin honors the 1984 Candidates Final Match won by Garry Kasparov against former World Chess Champion Vasily Smyslov. The 16-game series determined who would play Anatoly Karpov for the title of world chess champion.

Button from the 1979, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. Open Chess Championship

July 29-August 10, 1979

2 ½ in. diameter

Pin

Gift of John Donaldson

The 1979 U.S. Open Chess Championship brought players together for competition and to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the United States Chess Federation (now US Chess). US Chess was formed by the merger of two regional chess associations—the American Chess Federation and the National Chess Federation.

Commemorative Chess Pin

N.D.

1 3∕16 x 1 3∕16 in.

Pin

Gift of John Donaldson

An example of a popular pin in the chess world, this piece displays the black queen and knight behind a white pawn backed by a chessboard. This early version has a green and white chessboard. This enamel pin is an example of a technique of carving into a metal base to create indented areas that are then filled with enamel or glass. The piece is then exposed to heat to melt the enamel into place. The pin on display however appears to have had the white and green painted in after the black enamel was set.

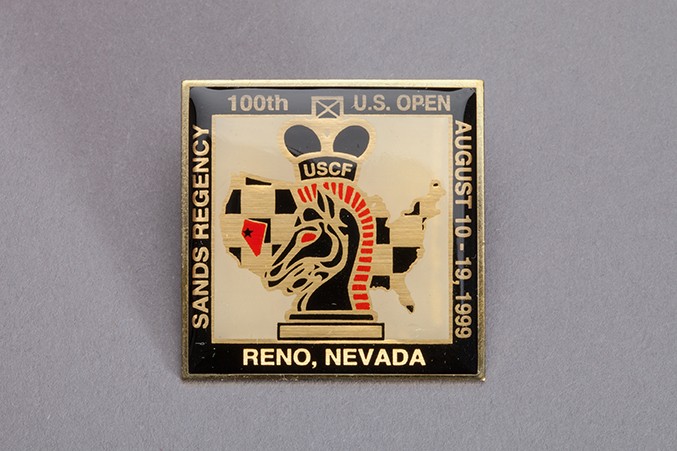

Pin from the 1999 Reno, Nevada, U.S. Open Chess Championship

1999

1 ½ x 1 ½ in.

Pin

Gift of John Donaldson

This pin honors the 100th U.S. Open Chess Championship. First organized by the Western Chess Association, a predecessor of US Chess, in 1900, the competition is an open national tournament. Alex Yermolinsky (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 2012), Alexander Goldin, Eduardas Rozentalis, Alexander Shabalov (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 2015), Gabriel Schwartzman, and Michael Mulyar won the 1999 edition.

Artifacts Featured in the Exhibition: Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis

Along with the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis (CCSCSL) and Q Boutique, the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) composes the Saint Louis Chess Campus. While the WCHOF honors important moments in chess history, the CCSCSL promotes the teaching of the game and holds a number of important tournaments and matches each year. Among these are the U.S. and U.S. Women’s Chess Championships, the U.S. Junior Closed Championship, and the Sinquefield Cup. After each of the events ends, staff from the two organizations collaborate to gather important artifacts from the competitions and make them part of the WCHOF’s collection. The artifacts on view in this section of the gallery only represent a small portion of the photographs, score sheets, and other mementos from Saint Louis competitions in the collection. More can be seen in the accompanying installation currently on view at the CCSCSL across the street.

Signed Chess Board from the 2013 Saint Louis, Missouri, Sinquefield Cup

2013

20 1∕8 x 20 in.

Vinyl board

Gift of the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis

Signed by the players in the first Sinquefield Cup, this commemorative chessboard celebrates a landmark competition in United States chess history. Named for Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield, the founders of the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis, and created in the tradition of the 1963 and 1966 Piatigorsky Cups, the Sinquefield Cup tournaments feature some of the strongest players from around the world. The 2013 Sinquefield Cup featured only four players—World Chess Champion Magnus Carlsen and Grandmasters Levon Aronian, Gata Kamsky, and Hikaru Nakamura—and was won by Carlsen. In subsequent years the tournament has featured an expanded field, first of six and now of ten players, furthering the organizers’ goal of promoting elite chess in the United States.

Zymo Sculpture Studio

Sinquefield Cup Trophy

2013

11 x 11 x 24 in.

Trophy

Collection of the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis

This oversized silver king is the perpetual trophy for one of the strongest American tournaments, the Sinquefield Cup, which is held annually in Saint Louis. The names of the 2013-2016 winners are engraved on the front. Each winner also receives a smaller “presentation” trophy as a keepsake of their victory. Designers of this trophy gathered inspiration from trophies as varied as the World Series, Wimbledon, and the Grammys, and staff at the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis and World Chess Hall of Fame voted and provided input on the design. Ultimately, the trophy was designed as a Staunton-style king, an appropriate representation of the top honors at the competition.

Artifacts Featured in the Exhibition: Photography

The World Chess Hall of Fame’s (WCHOF) collection contains a number of photographs, mostly dating from the 20th century, that document events and important players, both in the United States and around the world. The WCHOF’s holdings in this area have been boosted by three important gifts: the archives of Jacqueline Piatigorsky, which contain images from the competitions she organized and her own career as a player, as well as ones pertaining to her friend and mentor Herman Steiner; the archives of Walter Browne, which contain photography from the archives of his magazine Blitz Chess; and the ongoing donations of photography from competitions held at the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis. Photographs like these offer insight into the personalities of some of the game’s most famous players.

Igor Utkin/TASS

GM Maya Chiburdanidze (U.S.S.R.) vs WGM Irina Levitina (U.S.S.R.) at the 1984 Volgograd, Russia, Women’s World Chess Championship

October 1984

6 1⁄4 x 9 7∕16 in.

Photograph

© Igor Utkin

Reigning Women’s World Chess Champion Maya Chiburdanidze defends her title from Irina Levitina in this photograph from the 1984 Women’s World Chess Championship. Their match was closely fought, but Levitina blundered in the ninth game, allowing Chiburdanidze to win. Chiburdanidze then earned three and a half points in their final games, earning her the title again. 2014 World Chess Hall of Fame inductee Chiburdanidze was only the second woman to earn the title of grandmaster and held the title of women’s world chess champion from 1977 to 1991. Levitina later immigrated to the United States, where she went on to win three U.S. Women’s Chess Championships (1991, 1992, and 1993).

Photographer unknown

Competitors Playing in the 1915 New York Masters Tournament

1915

8 1∕16 x 9 15∕16 in.

Photograph

Gift of Kathy Cella

Kathy Cella, the granddaughter of 2013 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Abraham Kupchik, donated this photograph to the World Chess Hall of Fame. The 1915 New York Masters Tournament, an invitational 8-player round robin tournament, featured players from around the world. In the opening round, competitors posed to be recorded by Pathé News, which intended to circulate a film that would better acquaint the public with famous chess players. Seated in the front of this photo (L to R) are: Jose Raul Capablanca, Edward Lasker, Jacob Bernstein, and Frank Marshall. Seated behind them are: Abraham Kupchik, Oscar Chajes, Albert Hodges, and Einar Michelson. In the background are: Gustav Koehler, R.J. Brown, L. Rosen, F.P. Beynon, John L. Clark, Hermann Helms, Frank I. Cohen, Julius Finn, Hartwig Cassel, W. M. Visser, Aristides Martinez, Frank Marshall Jr., and Caroline Marshall. Capablanca won the tournament, just ahead of Marshall. Chajes and Kupchik finished tied in third place.

Photographer unknown

Hans Berliner Demonstrates at the 1959 North Central Open Class Chess Tournament

1959

8 1∕8 x 10 in.

Press photograph

Hans Berliner demonstrates his chess technique before an eager crowd of fans at the 1959 North Central Open Chess Tournament. The competition, organized by the Wisconsin Chess Association, was held from November 26-29, 1959, at the Hotel Astor in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Advertisements noted that it was the most popular open tournament in the country after the U.S. and Western Opens. Berliner (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 1990) won a number of regional tournaments throughout his career and would become a World Correspondence Chess Champion only six years after this competition.

Photographer unknown

Marshall Chess Club Dinner in Honor of Larry Evans and James T. Sherwin held at the Fifth Avenue Hotel, New York, New York

October 24, 1951

9 15∕16 x 19 7∕8 in.

Reproduction of a photograph

Gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

© Sterling N.Y. PL-8-2702

An array of American chess luminaries gather at a dinner organized by the Marshall Chess Club in honor of Larry Evans, who had won the first U.S. Chess Championship of his career, and James Sherwin, who had won the New York State Chess Championship. Named for its founder, Frank Marshall, the Marshall Chess Club is one of the oldest and most well-known chess clubs in the United States. Caroline Marshall, the club’s manager, organized this dinner during the 1951 U.S. Women’s Chess Championship, which the Marshall Chess Club partially hosted. Among the many attendees pictured here are players from competition, including its eventual winner Mary Bain (pictured third from the left in the foreground). Jacqueline Piatigorsky, who competed in the U.S. Women’s Chess Championship for the first time in 1951, once owned the original of this photograph, which is too fragile for display, and labeled herself and her good friend Herman Steiner in it.

Photographer unknown

Judit Polgar Playing Against a Chess Computer

Date unknown

5 1∕16 x 7 3∕16 in.

Photograph

Gift of Raquel Browne © S.V.P. Photo: W.P.W.

In this photograph, Judit Polgar, the youngest of the three famous “Polgar sisters” is pictured playing chess against a computer. Polgar is the highest rated female player of all-time and in 2005, was the first woman to compete in the World Chess Championship. Polgar and her sisters, Susan and Sofia, famously trained with their father Laszlo, who believed that genius could be cultivated.

Artifacts Featured in the Exhibition: Posters

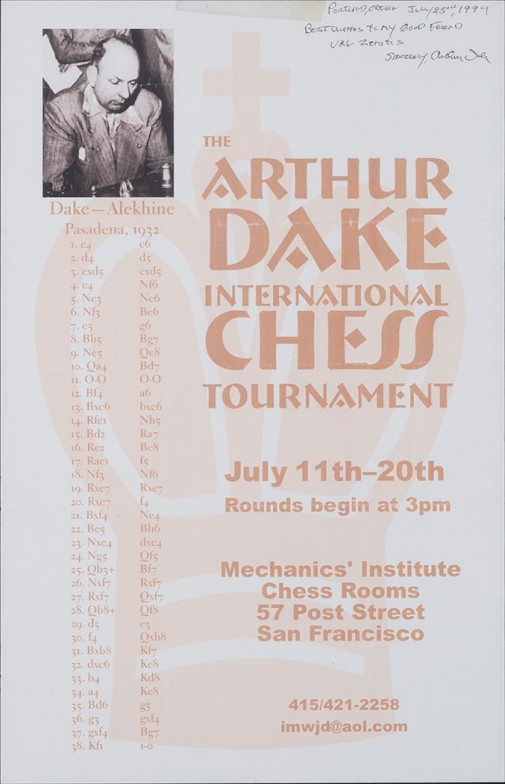

Poster from the 1999 San Francisco, California, Arthur Dake International Chess Tournament

1999

17 x 11 in.

Poster

Gift of John Donaldson

Grandmaster Arthur Dake was a member of the 1931, 1933, and 1935 gold-medal winning United States Olympiad teams. His score of 15 ½ out of 18 at Warsaw 1935 was the highest percentage (85%) of any player in the event.

One of the greatest talents in the history of American chess, Dake only learned to play chess at 17. Five years later he defeated World Champion Alexander Alekhine at Pasadena 1932. This was not the first time the two had met over the board. Three years earlier Dake traveled to California to play Alekhine in two simultaneous exhibitions. The first in Los Angeles saw the teenager earn a draw but a few nights later the World Champion got his revenge at the Mechanics’ Institute Chess Club in San Francisco, winning in only 17 moves. One bright spot for the teenager was this was the beginning of a 70-year relationship with the oldest continuously operated chess club in the United States (founded 1854).

The Mechanics’ held a tournament in July of 1999 to commemorate the U.S. Hall of Famer’s (inducted 1991) first visit to the Mechanics’ and Arthur Dake attended. The tournament poster, signed by Dake, includes his famous win over Alekhine.

George Lois

Poster from the October 8–November 10, 1990, New York City, USA, Portion of the World Chess Championship

1990

28 x 22 in.

Poster

1990 marked the final year that Garry Kasparov and Anatoly Karpov would compete for the title of World Chess Champion. Over the course of 5 World Chess Championship matches, the two citizens of the Soviet Union played 143 games. In describing the players’ rivalry writers often referred to the differences in their playing styles and personalities, as well as their relationships with the Soviet government, which helped to fuel their conflict. Steven Greenhouse, writing of the event for the New York Times, stated, “The match, which began in New York on October 8, pitted two opposites against each other. Mr. Kasparov is a fiery, creative, attacking player, while Mr. Karpov, who was world champion for a decade before Mr. Kasparov dethroned him, is a careful, phlegmatic finesse player. Mr. Kasparov, an ardent nationalist, is an avowed opponent of the Soviet President, Mikhail S. Gorbachev, while Mr. Karpov has long been hailed as a model Soviet citizen and was close to the former Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev.” Kasparov would go on to win the match, which was held partially in New York and partially in Lyons, France.

Poster from the 1984 Berkeley, California, U.S. Chess Championship

1984

19 x 8 ½ in.

Poster

Promoting the 1984 U.S. Chess Championship, this poster pictures the golden bear, the mascot for the University of California, Berkeley, atop a chess piece. The university hosted the tournament, which was won by Lev Alburt, a 2003 inductee to the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame. Artifacts like this one from the World Chess Hall of Fame’s collection illustrate the diversity of chess design, with venues for tournaments often offering a local twist on familiar chess imagery.

Roland Graphic

Poster from the 1981 Merano, Italy, World Chess Championship

1981

27 9/16 x 19 ½ in.

Poster

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Though in later years, Anatoly Karpov (World Chess Hall of Fame, 2004) earned attention for his rivalry with Garry Kasparov (World Chess Hall of Fame, 2005), his first rival as a reigning champion was fellow countryman Viktor Korchnoi. Korchnoi challenged Karpov for the championship twice—first in 1978 and second in 1981, when this poster was produced. As with Garry Kasparov, politics in the Soviet Union cast a shadow over their matches.

In 1974, Korchnoi and Karpov had competed for the chance to challenge reigning champion Bobby Fischer for the title. In that competition, Korchnoi accused Soviet authorities of interfering with the match due to their aversion to seeing a Jewish player win. In 1976, he defected from the Soviet Union. Two years later during their World Chess Championship match, the two accused each other of cheating, in a turbulent event filled with rumors of assassins and hypnotists.

At the outset of the 1981 Match, Korchnoi’s son was arrested by Soviet authorities, an event that some attributed as the cause of his poor play in the event, which Karpov won.

Victor Akhlomov

GM Anatoly Karpov (U.S.S.R.) and GM Garry Kasparov (U.S.S.R.) competing at a 1981 tournament in Moscow, Russia

1981

7 x 11 3/16 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame © Victor Akhlomov

In this photograph, rivals Anatoly Karpov and Garry Kasparov face off while a group of people observes. The crowd includes then-reigning Women’s World Chess Champion and future World Chess Hall of Fame inductee (2014) Maya Chiburdanidze, director of the Moscow Central Chess Club and high-ranking of cial in the Soviet Chess Federation Victor Baturinsky, Soviet Grandmaster Yury Razuvaev, and long-time Soviet/Russian chess journalist and photographer Yury Vasiliev. 1981 marked the first year that the two legendary players competed one-on-one. Only three years later, they would compete for the World Chess Championship for the first time, in a match that ended prematurely without result.

Chess Set, Board, and Box from the 2002 New York, New York, Garry Kasparov vs. Anatoly Karpov Exhibition Match

December 19-20, 2002

King height: 3 3⁄4 in.

Board: 20 7∕8 x 20 7∕8 in.

Box: 13 1⁄4 x 6 1⁄2 x 3 1⁄2 in.

Chess set, board, and box

Gift of Arnold H. Garcia

World Chess Champions Garry Kasparov and Anatoly Karpov used this equipment in a two-day exhibition match in ABC Studios. X3D Technologies, a producer of three-dimensional viewing equipment, sponsored the event, and encouraged visitors who owned a special viewer to watch the event in 3D from the comfort of their homes.

In the match, Karpov and Kasparov played two games of rapid chess per day. Karpov, who had not defeated Kasparov in a game since 1990, won the match, a result that surprised many viewers including chess champion and author Jennifer Shahade. In a December 21, 2002, article in the New York Times, she said, “Karpov’s victory is shocking. Garry has an aura of invincibility about him, and even when the last game was petering out to a draw, you expected him to somehow magically turn the game in his favor.” The match was the first in which Karpov triumphed over Kasparov.

Poster from the 1960, Leipzig, Germany, Chess Olympiad

Leipzig, Germany

1960

7 7∕8 x 5 ½ in.

Poster

This 1960 poster was used to advertise the 14th Chess Olympiad, which was held in Leipzig, Germany, that fall. The Chess Olympiad is a biennial international chess tournament, similar to the Olympics in that teams are sent by countries. However, only countries that are members of the World Chess Federation participate. The 1960 Chess Olympiad event in particular was rife with issues. At the time Leipzig was in Soviet-controlled East Germany, as demonstrated by the flag that runs along the bottom of the knight. In addition the U.S. and the Soviet Union were in the middle of the Cold War. Originally the United States State Department refused to support any team that went because they could not guarantee the protection of the competitors. However, with the approval of President Dwight D. Eisenhower a team was sent with players including Bobby Fisher and William Lombardy. Despite the turmoil of the event the U.S. team was able to place second after the Soviet Union.

Poster from the 1960, Leipzig, Germany, Chess Olympiad

Leipzig, Germany

1960

8 3∕16 x 5 ¾ in.

Poster

This 1960 Chess Olympiad poster sports a unique design of a seahorse in place of the more traditional knight. This piece is from the Meissen Company’s Porcelain Sea Life chess set. A showcase of German porcelain, the set was made around 1925 by master artisan Max Esser. The intricate seahorse was included on this Olympiad poster as a nod to German arts and culture. In many ways, the event served as a platform for the Soviet-controlled East Germany to prove itself to the rest of the world. If you wish to see the entire chess set, an example is displayed in the second floor exhibit Animal, Vegetable and Mineral: Natural Splendors from the Chess Collection of Dr. George & Vivian Dean.

Artifacts Featured in the Exhibition: Specialty Sets

House of Staunton

Marshall Series Staunton Chess Set

2016

King size: 4 in.

Chess set

Gift of The House of Staunton, Inc.

Staunton sets represented the culmination of an effort to create a standardized chess sets for play in tournaments. Nathaniel Cooke, an architect, created the iconic design, while his brother-in- law, John Jaques, manufactured the set. The iconic sets were named for and popularized by 2016 WCHOF inductee Howard Staunton (1810-1874). This set, named for 1986 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Frank Marshall is modeled on turn-of-the-20th-century Staunton sets, and was donated to the WCHOF on the occasion of Howard Staunton’s induction.

Ackerman Johnson Fastening Systems, Inc.

Wood and Masonry Anchor Chess Set

c. early 1990s

King size: 2 13∕16 in.

Chess set

Gift of Bud and Marlene Dale

The pieces in this set are comprised of wood and masonry anchors, which were products of Ackerman Johnson Fastening Systems, Inc. of Addison, Illinois. Bud Dale, one of the donors of this set, was a sales representative for the company for a number of years. The company president, Gerald Hagel, presented hand-crafted sets and boards like this one as Christmas presents to sales representatives.

Okuma America Corporation

Application Engineer Machined Commemorative Chess Set

2007

King size: 2 ⅞ in.

Chess set

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Hartwig Inc.

Manufactured for display at a September 2007 trade convention, this chess set showcases the intricate carving capabilities of the Okuma LT2000 EX. Controlled through a computer, this machine allows for the precise shaping of metals. Each of the pieces was made using a lathe, a machine that turns a piece of metal at a high speed while it is carved by a sharp tool. The logo of the Okuma Corporation is engraved on the bases of many of the pieces.

Herman Ohme

Ohme Chess

1960

King size: 3 5∕8 in.

Chess set © Herman Ohme

Marked by their mid-century Minimalist elegance, these chess pieces were designed by Dr. Herman Ohme. Ohme was an educator from California who decided to take a couple of years away from the teaching industry after receiving his doctorate. The design represents Dr. Ohme’s love of woodworking. He patented his abstracted design in 1954 and had originally intended the set to be sold in his own toy and game factory. However, he later licensed Pacific Games Co. to produce and sell the set when he chose to return to his teaching career.

Milton Bradley

Michael Graves Chess and Checkers Set

2013

King size: 2 in.

Chess and checkers set

Gift of Larry List

©Hasbro

Featuring bulbous, egg-shaped pieces, this chess set represents postmodern architect Michael Graves’ take on the game. First produced in 2000, the set was part of a line of sophisticated but affordable housewares designed by Graves and sold by the Target Corporation. In the following years, Graves produced travel-sized versions of the set and, after leaving the Target Corporation to form a partnership with JCPenney, made a slightly enlarged version with a different board.

Artifacts Featured in the Exhibition: Walter Browne

2003 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Walter Browne was a dominant force in American chess and won six U.S. Chess Championships. He excelled in open tournaments, earning shared or outright first place in the American Open seven times, the National Open eleven times, the U.S. Open three times, and the World Open three times. Browne passed away in 2015, and following his death, his wife donated his chess effects to the World Chess Hall of Fame.

Arthur Swoger

Walter Browne with His Trophies from the 1966 U.S. Junior Closed Chess Championship

1966

9 15∕16 x 8 in.

Photograph

Gift of Raquel Browne

In this photograph, Walter Browne poses with trophies from the first U.S. Junior Closed Chess Championship. This represents a significant moment in American chess and a link between two of the major donations represented in this exhibition, those of the estates of Jacqueline Piatigorsky and Walter Browne. Piatigorsky sponsored the first U.S. Junior Closed Chess Championship, in which the best young players in the United States competed, after learning that the country was not sending players to elite international tournaments for young competitors. The photo of the young champion appeared on the cover of the July 1966 issue of Chess Life.

Postcard from Walter Browne to his Family

1975

4 x 5 5∕8 in.

Postcard

Gift of Raquel Browne

Walter Browne sent this charming postcard to his family from the 1975 Hoogovens Tournament, which was held in Wijk aan Zee, the Netherlands. Grandmaster Lajos Portisch won the tournament, and Browne shared sixth place with Grandmasters Jan Timman and Efim Geller.

Walter Browne’s Travel Chess Set from the 1978 Buenos Aires, Argentina, International Master Chess Tournament

1978

King size: 1 in.

Board: 6 1⁄4 x 7 1⁄2 in.

Pocket chess set

Gift of Raquel Browne

One of the beauties of chess is that it can be played anywhere, and a wallet set produced in England in the 1930s, was the first design that made it easy to do so. This type of set became especially popular in the late 1950s when an Argentine model became the favorite of many leading grandmasters including the young Bobby Fischer. This set belonged to U.S. Chess Hall of Famer (inducted 2003) Walter Browne, who also advertised it for sale in his magazine Blitz Chess.

Walter Browne’s Chess Clock

Date unknown

5 1⁄4 x 8 1⁄4 x 11∕16 in.

Chess clock

Gift of Raquel Browne

Grandmaster Walter Browne was a true chess lover who liked nothing more than to compete. The six-time United States champion enjoyed playing six-hour tournament games, but nothing gave him more pleasure than a long session of five minute chess. The U.S. Chess Hall of Famer was so fond of chess played at a fast time control that he founded the World Blitz Chess Association (WBCA) and published the magazine Blitz Chess for fifteen years (1988-2003).

Browne not only published a magazine and ran the WBCA with its own rating system and special rules for blitz chess, he also helped develop clocks designed to make keeping track of time easier. Before the 1980s analog clocks (like the other model on view in this exhibition) reigned supreme, but the faces of the clocks were not easy to read for someone down to a few seconds and the flags for the various models all seemed to fall a little differently. This usually didn’t matter for tournament games played at longer time control, but it often caused problems in five minute games, frequently leading to arguments.

Several clock designers sought to rectify this problem by producing the first digital clock, and Walter helped them by testing models (one early prototype is seen here) and providing valuable feedback. By the mid-1980s several models (Caissa and Chronos being two) were regularly being employed in tournaments.

Jerger

Walter Browne’s Jerger Chess Clock

Date unknown

2 1⁄2 x 7 11∕16 x 4 1⁄2 in.

Chess clock

Gift of Raquel Browne

Herff Jones

Walter Browne’s 1981 South Bend, Indiana, U.S. Chess Championship Ring

1981

1 x 7∕8 in. (ring)

1 11/16 x 2 x 2 5∕8 in. (Box)

Ring

Gift of Raquel Browne

Walter Browne earned this ring in recognition of his victory in the 1981 U.S. Chess Championship, the fifth of his six wins in the elite tournament. He shared the honors with Grandmaster Yasser Seirawan, who would go on to hold the title four times himself. In 2014, the pair met at the World Chess Hall of Fame for a lecture titled “A Conversation with Walter Browne,” in which Browne and Seirawan reminisced about the former’s chess career.

Press

3/7/17: Art Daily — Exhibition at the World Chess Hall of Fame showcases collection, celebrates five years in Saint Louis

9/20/16: Webster-Kirkwood Times — World Chess Hall of Fame Celebrates 5th Anniversary

9/20/16: Chess Base — Three new exhibitions at the World Chess Hall of Fame

9/18/16: Chessdom — World Chess Hall of Fame celebrates five years in Saint Louis