Described as a “Dadaist love story,” Une danse des bouffons (or A jester’s dance) is Dzama’s fictionalized account of the romantic affair between artists Marcel Duchamp and Maria Martins.

On View: May 14 – October 18, 2015

Featuring Kim Gordon and Hannelore Knuts (both playing the role of Martins in alternating versions of the film) and a surreal panoply of elements derived from art, dance, and chess, Mischief Makes a Move is an exploration of the mythological figure known as the Trickster, whose pranks frequently blur the line between good and evil.

Described as a “Dadaist love story,” Une danse des bouffons (or A jester’s dance) is Marcel Dzama’s fictionalized account of the real-life romantic affair between the Dada artist and chess master Marcel Duchamp and the Brazilian sculptor Maria Martins. Featuring musician Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth, Belgian actress and model Hannelore Knuts (both playing the role of Martins in alternating versions of the film), and a surreal panoply of elements derived from art, dance, and chess, Mischief Makes a Move is an exploration of the mythological figure known as the Trickster, whose pranks frequently blur the line between good and evil. Commissioned by the 2013 Toronto International Film Festival, Une danse has been shown at the Kunstmuseum Thun in Switzerland, the David Zwirner Gallery in New York, and now in Saint Louis at the World Chess Hall of Fame. Created as an homage to the famed Canadian filmmaker David Cronenberg, the film also includes references to Dzama’s artistic heroes including Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Joseph Beuys, Francisco de Goya, and Oskar Schlemmer, among others. The score is composed by Will Butler, Jeremy Gara, and Tim Kingsbury—all members of the band Arcade Fire.

Centered on Une danse, Mischief Makes a Move includes sculptures, masks, dioramas, and works on paper inspired by the film as well as a chess set created exclusively for this exhibition. Additional works in the show include the videos Robot Chess (2014), which is on view in the gallery, and Death Disco Dance (2011). Displayed in the front window of the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF), the latter work presents an array of dancers dressed as chess pieces to visitors and passersby at the Saint Louis Chess Campus. In 2012, the WCHOF was honored to serve as the venue for the artist’s first solo exhibition in the Midwest titled Marcel Dzama: The End Game. The WCHOF is proud to bring Dzama, whose work beautifully complements our mission to celebrate the intersection of culture, art, history, and chess, back to Saint Louis.

—Shannon Bailey, Chief Curator

Marcel Dzama

Born in 1974 in Winnipeg, Canada, Marcel Dzama’s work is inhabited by an expansive cast of recurring human, animal, and hybrid characters. Typically manipulating a distinctive palette of muted browns, grays, greens, and reds, the artist has developed an immediately recognizable visual language that penetratingly explores human action and motivation, often by means of the violent, erotic, grotesque, and absurd. His practice unleashes a universe of childhood fantasies and otherworldly fairytales, drawing equally from folk vernacular as from artistic influences that include Dada and Marcel Duchamp. Widely known for his works on paper, Dzama has in recent years expanded his practice to include sculpture, painting, film, large-scale polyptychs, and dioramas. In the latter, he constructs intricate, complex, three-dimensional scenes using his signature drawings, collage elements, cardboard, and occasionally ceramics. He creates a cast of human figures, animals, and imaginary hybrids to life, and has developed an international reputation and following for his art that depicts fanciful, anachronistic worlds.

Dzama’s work has been the subject of several solo exhibitions, most recently in 2011 at Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, The Netherlands, and Kunstverein Braunschweig, Germany. In 2010, a major survey was organized by the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, Canada. Other important solo exhibitions include the Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich (2008); Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, England; Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow (both 2006); and Le Magasin – Centre National d’Art Contemporain de Grenoble, France (2005). His work has been featured in numerous group exhibitions internationally, including the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco (2011 and 2009); Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax, Canada (2009 and 2004); The Museum of Modern Art, New York (2009, 2008, 2006, and 2005); P.S.1. Contemporary Art Center, Long Island City, New York (2006); Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2006); among others.

Dzama’s work is in the collections of major museums and public institutions, including the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, New York; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Dallas Museum of Art; Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, Canada; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Tate Gallery, London; and the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Since 1998, his work has been represented by David Zwirner, New York. The artist lives and works in New York.

“The tricks of today are the truths of tomorrow.”

—Man Ray

Marcel Dzama was born on May 4, 1974, in Winnipeg, Canada. The oldest of three children in a working-class family, drawing was an inexpensive outlet for creative energies, especially during the oppressively cold Manitoba winters. The seeds of his prolific nature as an artist were sown early on in his childhood, when he was already redrawing the images in his coloring books after all of the uncolored spaces had been filled. He graduated to comic book superheroes for inspiration, as well as his father’s collection of reprints of the iconic Prince Valiant comic strip, whose creator, Hal Foster, had lived and worked in Winnipeg during his teens and twenties. The young Marcel also showed a considerable appetite for his father’s collection of illustrated classics, and it was this continued preference for drawing over writing that ultimately signaled a far less benign condition than simply a boyhood love for illustration. In grammar school he was diagnosed with dyslexia, and for several years was shuttled to a school that offered alternative programs for learning English. Despite some improvement in his reading, these results faded when he returned to the conventional educational system, which consequently pushed him deeper into his drawing.

Dzama attended the School of Art at the nearby University of Manitoba, where he studied with Alison Norlen, whose unobtrusive approach to mentoring gave him the space and freedom to develop on his own. Norlen not only introduced him to like-minded artists from the past, such as the Surrealists André Masson and Joseph Cornell, she also encouraged him to approach the history of art as a resource without fear of appearing derivative, guidance that would have a lasting effect on his artistic development. His courses made liberal use of the Winnipeg Art Gallery, where he found the massive collection of Inuit art especially stimulating as it appealed to his inclination toward fantasy and mythology over reality, featuring a host of shape-shifting, animal/human hybrid creatures whose deceptively naïve execution belies the complexity of the shamanistic activities represented.

Even more crucial to his development at the School of Art was his role in the formation of a small group of highly compatible artists that came to be known as the Royal Art Lodge. In the wake of a devastating fire in his family home that forced them out of the house for several months in 1996, Dzama retreated more and more to his campus studio, where he and fellow Lodge members developed a process of collaborative drawing that demonstrated a strong collectivist ideology in the spirit of earlier movements like Fluxus. Eschewing personal gain, the communal methodology practiced by the Lodge (drawings were dated but not signed by individual members) has become quasi-legendary, and culminated in the exhibition Ask the Dust, organized by the Drawing Center in New York and the Power Plant in Toronto in 2003. The show brought the group international recognition, traveling to venues in Canada, Europe, Asia, and several cities in the United States.

Dzama’s own path to prominence led him to the sunny shores of Los Angeles, where Canadian curator Wayne Baerwaldt was curating an exhibition of up-and-coming artists at Richard Heller’s Santa Monica Gallery. Glowing reviews and a sold-out show led to a solo exhibition at Heller, quickly followed by solo shows at galleries all over North and South America. Dzama’s biggest break, however, came as a result of Heller showing several drawings at the Berlin Art Fair that caught the eye of David Zwirner, who offered to represent the artist. In the spring of 1998, just months after his first show in the United States, Dzama had a solo exhibition at Zwirner’s SoHo gallery and a review in the New York Times by Roberta Smith, who described his drawings as “both childish and perverse, like Winnie the Pooh illustrated by a devotee of A Clockwork Orange … With guns, knives and masks as frequent props, they have a climactic, often violent mood and sometimes evoke television Westerns or action movies. The images dart into view like uninvited dreams or fantasies triggered by who knows what—surfeits of rage, desire, or maybe just popular culture.”

Following several years of summers working in New York City and the rest of the year in Winnipeg, Dzama made the permanent move to New York in 2004. By the time of the move, he had already compiled a considerable resume of solo exhibitions, including Drawings for Dante (2002) and The Last Winter (2004), both at the Timothy Taylor Gallery in London; Welcome to Winnipeg (2003) at the Rizziero Arte in Pescara, Italy; Drawings by Marcel Dzama: From the Bernardi Collection (2003) at the Art Gallery of Windsor in Canada; as well as numerous eponymous exhibitions at Sies + Höke in Düsseldorf, Germany, and other European and North American galleries. By 2004 Dzama had also established his relationship with Dave Eggers’ publishing house McSweeney’s, which had already produced his first artist’s book The Berlin Years (2003), and would follow with a second edition of The Berlin Years (2006) and The Berliner Ensemble Thanks You All (2008). New York City broadened Dzama’s purview dramatically, as the increasingly dense and expansive compositions seen in the exhibitions The Course of Human History Personified (2005) and Tree with Roots (2006) attest.

In 2006, Dzama was invited by José Noé Suro to work at his ceramics workshop Ceramica Suro in Guadalajara, Mexico. There Dzama was able to create work on a scale that matched his rapidly evolving vision, resulting in the epically scaled dioramas shown in Even the Ghost of the Past (2008) at Zwirner’s New York space. This exhibition also saw Dzama’s most direct engagement with the Dadaists, particularly Marcel Duchamp, in whom Dzama found a level of kinship that transcends influence. The significance of Duchamp for Dzama’s artistic evolution can hardly be evoked without mentioning the former’s deep passion for chess, which is so densely interwoven in the fabric of Duchamp’s legacy that it is virtually impossible to ignore. Indeed, following his directorial debut with The Infidels (2009) and his first major survey Aux mille tours/Of Many Turns (2010) at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, Dzama directed the ambitiously conceived film A Game of Chess (2011), the centerpiece of his exhibition Behind Every Curtain (2011) at Zwirner. Shot in Guadalajara, A Game of Chess evokes the feel of 1920s avant-garde film with its obscurely interwoven parallel story lines that alternate between a woman’s fantasy of being trapped in a chess-match ballet and her reality of being an assassin in an unidentified war-torn land. In addition to nods to Dadaists like Duchamp and Francis Picabia, the work of this period abounds with references to his emerging interest in dance, inspired by the grotesquely surreal dance sequence from the Technicolor extravaganza The Red Shoes (1948) and the costumes and choreography of Bauhaus polymath Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet (1922).

With time to spare following the filming of A Game of Chess, Dzama and the performers quickly improvised another film called Death Disco Dance (2011), which was shot nearby outside of the recently torn-down factory of a company coincidentally named Canada Shoe. The masked dancers in polka-dotted unitards (inspired by Picabia’s costume designs for the ballet Relâche) who represented the pawns in A Game of Chess take center stage in this film, while the normally more mobile pieces shimmy in the background to a disco drum beat of Dzama’s own creation composed on a drum machine. Recalling Public Image Ltd.’s Death Disco in its title (and not, tempting though it may be to speculate, The Smiths’ Death of a Disco Dancer), the film plays tricks with time and continuity, as the stops and starts of the music’s synthetic beat are mirrored in the subtle but visible loops and reversals of the film, creating a spasmodic continuity in the repetitive movements of the lithe and anonymous dancers, one of whom still inexplicably bears a gruesome wound sustained in A Game of Chess.

Duchamp remains at the heart of Dzama’s Une danse des bouffons (or A jester’s dance), which was commissioned by the Toronto International Film Festival and debuted at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art in Toronto in 2013 as part of an exhibition of artists influenced by Canadian filmmaker David Cronenberg, with whom Dzama shares a penchant for violent imagery and a dark, often inscrutable psychology. Une danse casts Dzama’s menagerie of characters and beloved art historical references in a surreal account of the unmarried Duchamp’s affair with the married sculptor Maria Martins, which lasted from the mid-1940s until Martins ended the relationship despite Duchamp’s protestations by moving permanently back to her home country of Brazil in 1950. Martins, who was in the United States during the 1940s with her second husband and Brazilian ambassador to the United States Carlos Martins, was long speculated and is now known to have been the model for the nude torso in Duchamp’s grand final opus, Étant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau, 2° le gaz d’éclairage . . . (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas . . .). Assembled in secret during the last two decades of Duchamp’s life, it is a haunting tableau of an undressed figure laying supine in the brush with her face obscured holding a gas lamp aloft before a deep landscape with a waterfall, all of which is viewed through two peepholes in a weathered wooden door. How an artist of Duchamp’s notoriety was able to construct a work of such magnitude in secret remains a mystery to many. However, it is easy to forget that Duchamp was not as heralded in the 1940s and 1950s as he is today, and many were still under the misapprehension that he had given up art to pursue his professional chess ambitions.

Following Duchamp’s death in 1968, Étant donnés was installed, per his wishes, in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where in 2003 Dzama would encounter it in person for the first time. Five years later, Dzama exhibited his own tableau at Zwirner titled Even the Ghost of the Past (2008), an installation in which one finds what Dzama suspects one would see if the view of Étant donnés were expanded to the left, revealing not only the woman’s face, but also a similarly nude and recumbent male figure identified by Dzama as Duchamp. Dzama was inspired to engage with this particular work because it seemed to provide a rare and revealing glimpse into the normally opaque and coldly conceptual mind of a man who clearly possessed a sentimental side to his complex personality.

“Something about Étant donnés really struck me when I first saw it,” Dzama recalled. “There was also the fact that it was like a love letter to his mistress and his last wife. It was just really a beautiful story that found its way into some of the work that I was doing.”

Marcel Dzama

Even the Ghost of the Past, 2008

Diorama: brick, door, wood, taxidermied fox, glazed ceramic sculptures, acrylic on blackboard

Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

Enigmatically standing over the doomed lovers in Even the Ghost of the Past is a stuffed fox, an animal that numerous cultures worldwide associate with the Trickster, a mythological and literary type who presents a disruptive element, upending convention and cultivating chaos, sometimes in a malevolent spirit and at other times to the benefit of others by showing them the folly of their own narrow perspectives or attitudes. Fueled by duality, the Trickster, whose role is substantially expanded in Une danse, thrives on playing both sides, confusing traditional binaries like good and evil or love and hate. In the film, the woman representing Martins (played by both indie-rock star Kim Gordon and Belgian model and actress Hannelore Knuts in two different but nearly identical versions of the film) seeks to rescue the man representing Duchamp (played by artist Jason Grisell), who plays both the victim and the victimizer. Chess, which at one time liberated Duchamp from having to make art, now holds him captive, with gun- and camera-wielding terrorists forcing him to mindlessly recite chess moves. Many of the elements of the film are doubled, with Duchamp conspicuously playing both the captive and the captor. Maria represents Duchamp’s salvation, and yet, according to Dzama, it is also her face behind the double mask of the executioner, whose impish dance was choreographed and performed with nefarious panache by Vanessa Walters.

In true Dzama style, the supporting roles are helmed by a survey of his chosen art historical ancestry, most notably Francsico de Goya, with his sinister and surreal Los Caprichos (also the source of the perversely stylized arabesque cursive that titles many of Dzama’s drawings) and the pseudo-mythically constructed artist/shaman/Teuton Joseph Beuys, complete with his “coyote.” The coyote (played here by the stuffed fox from Even the Ghost of the Past) is another common manifestation of the Trickster in native North American cultures and a reference to Beuys’ legendary cohabitation with a wild coyote in the performance I Like America and America Likes Me (1974). But perhaps the most critical figure for Duchamp from the Dzama pantheon is Picabia, for, according to Dzama, Duchamp became a significantly more compelling artist after he was introduced to Picabia in Paris in 1911. In the end it is Picabia, represented by the berobed and venerated cow from his painting The Adoration of the Calf (1941), whose frightening visage Picabia had previously purloined from Erwin Blumenfeld’s macabre photograph The Dictator/Minotaur (1937), who holds the key to Duchamp’s true salvation. Duchamp must be symbolically reborn through his bon vivant friend in order to break down the psychic walls erected by a lifetime’s obsession with chess. Following Duchamp’s Cronenbergian quasi-natal emergence from a vulvic opening in the calf’s chest, the film loops back to beginning, and we are left to replay the purgative cycle of love, torture, death, and rebirth over and over again until lie becomes fact, fiction becomes truth, and the star-crossed lovers are united once more.

—Bradley Bailey, 2015

Works Featured in the Exhibition

Marcel Dzama

Une danse des bouffons (or A jester’s dance), 2013

Video projection, 35:22 min, black and white, sound

Dimensions variable

Une danse des bouffons (or A jester’s dance) casts Marcel Dzama’s menagerie of characters and beloved art historical references in a surreal account of the unmarried Marcel Duchamp’s affair with the married sculptor Maria Martins. Martins is now known to have been the model for the nude torso in Duchamp’s grand final opus, Étant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau, 2° le gaz d’éclairage. . . (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas. . .). Assembled in secret during the last two decades of Duchamp’s life, it is a haunting tableau of an undressed figure lying supine in the brush with her face obscured holding a gas lamp aloft before a deep landscape with a waterfall, all of which is viewed through two peepholes in a weathered wooden door.

In the film, the woman representing Martins (played by both indie-rock star Kim Gordon and Belgian model and actress Hannelore Knuts in two different but nearly identical versions of the film) seeks to rescue the man representing Duchamp (played by artist Jason Grisell), who plays both the victim and the victimizer. Chess, which at one time liberated Duchamp from having to make art, now holds him captive, with gun—and camera—wielding terrorists forcing him to mindlessly recite chess moves. Many of the elements of the film are doubled, with Duchamp conspicuously playing both the captive and the captor. Maria represents Duchamp’s salvation, and yet, according to Dzama, it is also her face behind the double mask of the executioner, whose impish dance was choreographed and performed with nefarious panache by Vanessa Walters.

—Bradley Bailey, 2015

Marcel Dzama

Death Disco Dance, 2011

Video on monitors, 4 min (loop), color, sound

Dimensions variable

Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

Marcel Dzama

Death Disco Dance (Installation at WCHOF), 2015

Video on monitors, 4 min (loop), color, sound

Following the filming of A Game of Chess (2011), Dzama and the performers improvised another film called Death Disco Dance (2011), which was shot nearby outside of the recently torn-down factory of a company named Canada Shoe, a coincidental reference to his Canadian heritage. The masked dancers in polka-dotted unitards (inspired by Francis Picabia’s costume designs for the ballet Relâche) who represented the pawns in A Game of Chess take center stage in this film, while the normally more mobile pieces shimmy in the background to a disco drum beat of Dzama’s own creation composed on a drum machine. The film plays tricks with time and continuity, as the stops and starts of the music’s synthetic beat are mirrored in the subtle but visible loops and reversals of the film, creating a spasmodic continuity in the repetitive movements of the lithe and anonymous dancers, one of whom still inexplicably bears a gruesome wound sustained in A Game of Chess.

Marcel Dzama

Robot Chess (still), 2015

Video on monitor

Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

Considered to be the most influential artist of the 20th century, Marcel Duchamp was also an accomplished chess player. Declared a Chess Master in 1924 by the French Chess Federation, Duchamp competed in several international tournaments including the 1930 Hamburg Chess Olympiad. During that competition, Duchamp (black) drew a game against Frank Marshall (white). One of the top players in the world, Marshall held the title of United States Chess Champion from 1909 until he resigned it in 1936. He is an inductee to the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame and his commemorative plaque is located in the 3rd floor gallery of the World Chess Hall of Fame. The Marshall Chess Club, which he founded in 1915 in New York City, is still in operation and is one of the oldest chess clubs in the United States.

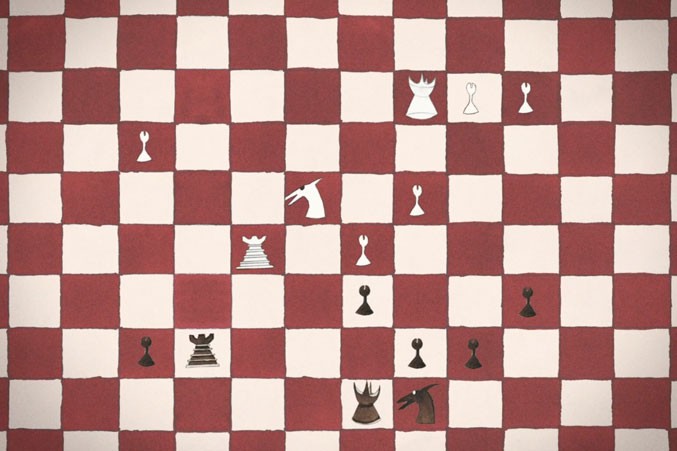

The chess pieces shown are based upon imagery in Dzama’s 2011 film A Game of Chess as well as Duchamp’s rubber stamp chess figures the famed artist designed for correspondence games.

Marcel Dzama

A blue box for Marcel, 2013

Fabric, acrylic, wood, plaster, metal, paper, vinyl, porcelain, film, plastic flower, graphite, collage, and string

Dimensions vary

Dzama combines two of Duchamp’s artistic projects The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box) (1934) and Boîte-en-valise (1935-40). The Green Box contains numerous notes on scraps of paper describing the process of creating one of his masterpieces, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) (1915–23). The Boîte-en-valise, on the other hand, was a miniature “museum” of tiny replicas of the artist’s own work.

A variety of references to Dzama’s art—some from this new body of work, and some from earlier pieces—are presented here. Arranged similarly to Duchamp’s work, the pieces all fit meticulously in a valise/suitcase with expanding wings.

Marcel Dzama

Pot head philosopher, 2014

Papier-mâché, plastic flowers, spray paint, and acrylic and wood pedestal

Overall: 81 x 67 x 34 inches

Marcel Dzama

Pot head, 2014

Papier-mâché, plastic flowers, spray paint, and acrylic and wood pedestal

Overall: 84 x 35 x 31 inches

To evoke the atmosphere of an old-fashioned movie palace, Dzama created these vases to flank the viewing area for his film. Both vases have four eyes, matching the judge in Une danse des bouffons. Additional characters appearing in work in this exhibition have the same attribute. Red and blue appears throughout work in this exhibition, including in the color of the flowers bursting from the tops of the bases. This palette is inspired by stories about the Nigerian Trickster god Edshu, who painted his hat blue on one side and red on the other. He repeatedly walked along a path causing the farmers on each side to fight and argue about the color of their god.

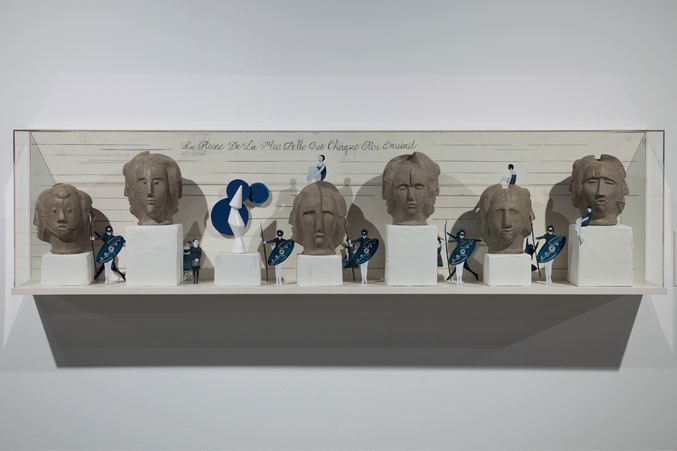

Marcel Dzama

The fairest queen that every king envied, 2014

Cardboard, tape, gouache, papier-mâché, and graphite

Diorama: 14 x 56 1/4 x 7 inches

In this diorama, scaled-down versions of the Oskar Schlemmer-inspired masks are lined up on a variety of tiny pedestals flanked by ballerinas. The queen, stationed on the third pedestal on the left, is based upon a chess set created by the Surrealist artist Max Ernst.

Marcel Dzama

The grandmasters hall of fame, 2014

Cardboard, tape, gouache, papier-mâché, and graphite

Diorama: 14 x 56 1/4 x 7 inches

Red and black ballerinas dance around an impressive list of grandmasters including from left to right: Grandmaster [Paul] Morphy, Grandmaster [Judit] Polgar, Grandmaster [Emanuel] Lasker, Grandmaster Flash, Grandmaster [Wilhelm] Steinitz, Grandmaster [Viswanathan] Anand, and Grandmaster [Garry] Kasparov.

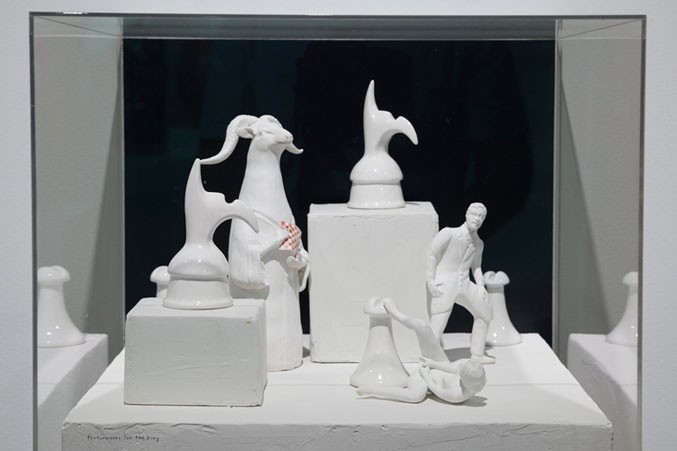

Marcel Dzama

Procession for a pawn, 2014

Porcelain, wood, acrylic, spray paint, and vinyl in Plexiglas and wood vitrine

Vitrine: 17 1/4 x 17 x 17 inches

Known for his elaborately detailed two-dimensional dioramas, Dzama created this series of three- dimensional dioramas featuring characters from the film as well as figures in sexual and violent situations. He repeatedly explores both subjects through his pieces. As with much of the work included in this exhibition, Dzama imagined what it would be like to follow several of the characters through new adventures, placing them in additional situations and mixing them with characters from his past work. In the case of this series, Dzama views these vignettes as captured moments in a chess game.

Marcel Dzama

Everyone is making love or only watching, 2014

Porcelain, wood, papier-mâché, acrylic, and spray paint in Plexiglas and wood vitrine

Vitrine: 17 1/4 x 17 x 17 inches

Marcel Dzama

Performance for the king, 2014

Porcelain, wood, acrylic, spray paint, and vinyl in Plexiglas and wood vitrine

Vitrine: 17 1/4 x 17 x 17 inches

Marcel Dzama

Off with his head, 2014

Porcelain, wood, acrylic, spray paint, and vinyl in Plexiglas and wood vitrine

Vitrine: 17 1/4 x 17 x 17 inches

Marcel Dzama

We three kings, 2014

Printed steel and spray paint

18 1/2 x 9 1/2 x 10 1/2 inches

Marcel Dzama

The four kings lose, 2014

Printed steel, spray paint, and collage

17 x 14 1/2 x 14 1/2 inches

Masks are a recurring theme in Dzama’s work. Many are functional and have served as part of costumes in a variety of his films. These metal heads, all made in Guadalajara, Mexico, in 2014, are not wearable but instead are sculpture made from the cans of Jumex apple juice and La Costeña jalapenos—both Mexican food companies.

Marcel Dzama

We 4 kings, 2014

Printed steel and spray paint

18 x 12 x 14 inches

Marcel Dzama

The red king’s head, 2014

Printed steel and spray paint

17 x 14 1/2 x 14 1/2 inches

Marcel Dzama

Golden Knight, 2014

Papier-mâché and spray paint

16 x 16 x 10 1/2 inches

This wearable mask is inspired by the costumes of the German painter, sculptor, and choreographer Oskar Schlemmer (1888-1943). His most famous work is Triadisches Ballett (Triadic Ballet), which deeply influences the work of Dzama through both its movement and costumes.

Marcel Dzama

Golden Calf, 2014

Papier-mâché and spray paint

18 1/2 x 19 x 23 inches

Featured as a major character in the film Une danse, the Calf figure references Francis Picabia’s painting Calf Worship (1948), which in turn was based on the photograph The Minotaur/Dictator (1937) by the Surrealist photographer Erwin Blumenfeld. In Une danse, Marcel Duchamp is reborn through the calf’s neck, symbolizing the real-life situation of Duchamp receiving artistic inspiration after spending time with Picabia.

Marcel Dzama

Bailiff and bishops number 1, 2014

Papier-mâché, plastic flower, and spray paint

26 1/2 x 23 1/2 x 17 inches

Marcel Dzama

Bailiff and bishops number 2, 2014

Papier-mâché, plastic flower, and spray paint

28 x 18 x 15 inches

Marcel Dzama

Bailiff and bishops number 3, 2014

Papier-mâché, plastic flower, and spray paint

27 x 17 x 17 inches

Based on the multi-faced masks worn by characters in Une danse des bouffons, these three heads are inspired by masks worn by dancers in Oskar Schlemmer’s ballets from the 1920s.

Marcel Dzama

Play It with Yoko (Guadalajara Version), 2015

Ceramic, 32 pieces

King size: 5 in.

Created in 2015 and exhibited for the first time at the World Chess Hall of Fame, this white versus white ceramic chess set stems from Dzama’s influences and past work. Based on characters from his 2011 film A Game of Chess, the pieces also refer to Duchamp’s chess stamps (as seen in other work in this gallery). The set also contains references to Mexican history, namely the conquistadors led by Hernan Cortes that fought and defeated Aztecs in 1521.

Marcel Dzama

Too many nights and only one queen or Long knights for a lonely queen, 2014

Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on paper

Paper: 14 1/8 x 16 3/4 inches

This drawing and watercolor honors Dzama’s art heroes. In plates 37-42 of his series of satirical etchings and aquatints titled Los Caprichos, Francisco de Goya gives human characteristics to donkeys to mock the ignorance of the aristocracy. The knight in the upper right corner of this piece appears in artwork throughout this exhibition and is based on a knight designed by Marcel Duchamp for a set of chess stamps he used to play correspondence chess through the mail. The lone blue piece pays homage to the queen in the famous set designed by Max Ernst for the Imagery of Chess exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York City in 1944-45.

Marcel Dzama

The fatal sister, 2014

Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on paper (4 part work)

Overall: 14 x 44 inches

Characters from Dzama’s current and past work, including hybrid creatures and several figures from his 2011 film A Game of Chess, animate The fatal sister. The upright chessboard and chess pieces on the sides of the work are references to Duchamp.

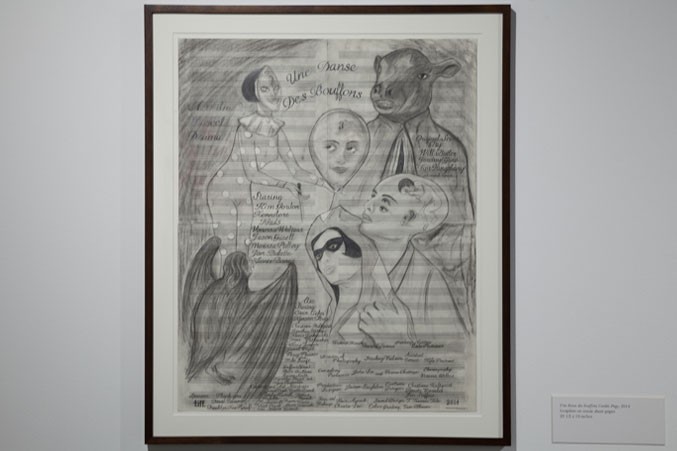

Marcel Dzama

Une danse des bouffons Credits Page, 2014

Graphite on music sheet paper

Paper: 23 1/2 x 19 inches

Marcel Dzama

This spark will prove a raging fire, 2014

Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on paper (6 part work)

Overall: 51 3/4 x 28 1/2 inches

In this watercolor, the Calf motif is shown emerging from a spray of rising flames that recalls the watercolors of British painter William Blake (1757-1827). The Calf oversees several characters from Une danse de bouffons, including the face of the Judge/Duchamp in the balloon held aloft at the lower left. The figure at the lower right and the coyote at the lower left make reference to German artist Joseph Beuys’ (1921-1986) I Like America and America Likes Me performance (May 1974), in which Beuys spent much of three days swathed in thick grey felt and holding a shepherd’s staff attempting to commune with a coyote.

Marcel Dzama

The queen with child, 2011

Ink, gouache, and graphite on paper

Paper: 14 x 11 inches

The central dancer in the geometric costume is the queen from Dzama’s film A Game of Chess (2011). Fetuses and pregnant women became a recurring motif in Dzama’s work during his wife’s pregnancy and the birth of their first child in 2012.

Marcel Dzama

Envying these creatures and their tenacious lust, 2014

Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on paper

Paper: 11 x 13 7/8 inches

Marcel Dzama

A monstrous red desire, 2014

Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on paper

Paper: 14 x 11 inches

Marcel Dzama

Where would I have got, if I had been intelligent, 2014

Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on paper

Paper: 17 x 14 inches

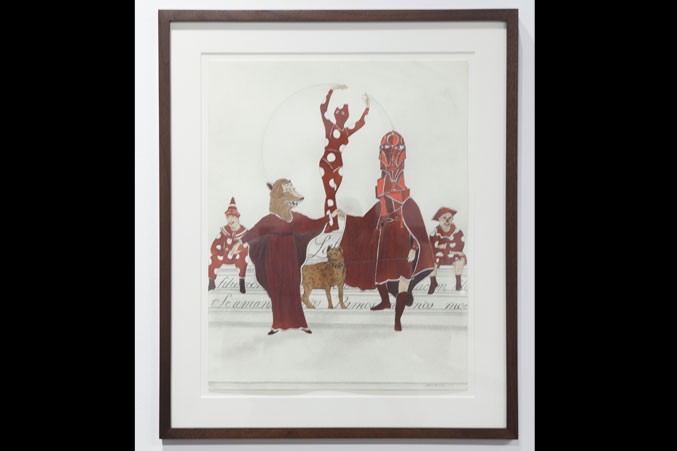

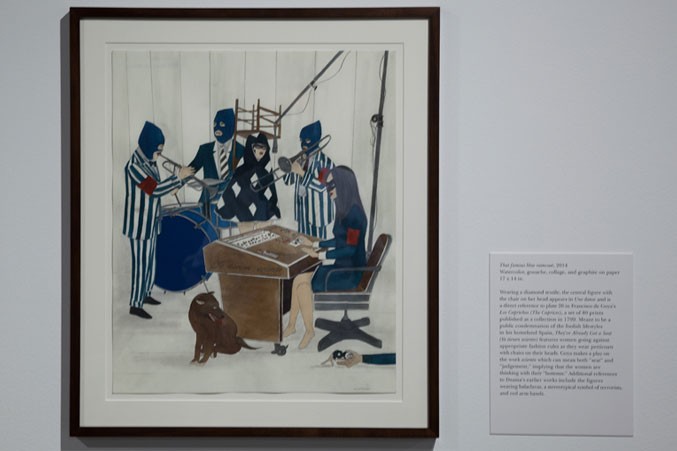

Marcel Dzama

That famous blue raincoat, 2014

Watercolor, gouache, collage, and graphite on paper

Paper: 17 x 14 inches

Wearing a diamond textile, the central figure with the chair on her head appears in Une danse and is a direct reference to plate 26 in Francisco de Goya’s Los Caprichos (The Caprices), a set of 80 prints published as a collection in 1799. Meant to be a public condemnation of the foolish lifestyles in his homeland Spain, They’ve Already Got a Seat (Ya tienen asiento) features women going against appropriate fashion rules as they wear petticoats with chairs on their heads. Goya makes a play on the word ‘asiento’ which can mean both “seat” and “judgement,” implying that the women are thinking with their “bottoms.” Additional references to Dzama’s earlier works include the figures wearing balaclavas, a stereotypical symbol of terrorists, and red arm bands.

PRESS

Marcel Dzama: Mischief Makes a Move Exhibition Release

11/1/15: 50 Moves — Coverage of the 2015 Sinquefield Cup by Ian Rogers (download)

10/9/15: The Streatham & Brixton Chess BlogWar Game 8 (and Some More Dzama)

9/7/15: The Chess Drum — Reflections of 2015 Sinquefield Cup

8/28/15: West End Word — “Mischief Makes a Move” World Chess Hall of Fame brings Dadaist Exhibition to Central West End

7/30/15: Alive Magazine — ALIVE Interview: Filmmaker Marcel Dzama, Who’s Bringing Dada Back (to the WCHOF)

5/22/15: Alive Magazine — ALIVE Q&A: Notable Artist Marcel Dzama Returns To The World Chess Hall Of Fame With Dadaist Silent Film

5/15/15: Yahoo! India — Photo of the Day: Une danse des bouffons

5/15/15: St. Louis Public Radio — Film and exhibit pursues surreal pairing of chess and avant garde art

5/15/15: ArtDaily.org — ‘Marcel Dzama: Mischief Makes a Move’ opens at the World Chess Hall of Fame in St. Louis

5/06/15: GALLERY OPENINGS IN ST. LOUIS — World Chess Hall of Fame: Thursday, 14 May 2015

4/23/15: AmericanTowns.com Exhibition – Marcel Dzama

Downloads

Mischief Makes A Move Brochure