In 2016, for the first time in 40 years, the American national team edged out 180 countries from around the world to win gold at the Chess Olympiad in Baku, Azerbaijan, solidifying America’s status as a powerhouse in the chess world. This multimedia exhibit features never before exhibited artifacts and honors the rich legacy—and bright future—of the American Chess Olympiad team.

On view: November 10, 2017 – March 31, 2018

Inspired by the American team’s victory in the 2016 Chess Olympiad, Global Moves: Americans in Chess Olympiads examines the competition through just one of the many lenses we could use to explore its long and storied history—the experiences of American players. Chess Olympiads are biennial tournaments in which teams of players work together to represent their countries. The early years of the tournament marked a golden age of American chess, when teams brought home team gold four times in a row. 2016 marked the first team gold achieved by the United States in 40 years, and the first time they had won team gold in an Olympiad that included Russia or the Soviet Union. The Kasparov Chess Foundation, Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis (CCSCSL), and US Chess offered support to the team, which included Grandmasters (GMs) Fabiano Caruana, Hikaru Nakamura, Wesley So, Sam Shankland, and Ray Robson, with International Master John Donaldson as team captain and GM Aleksandr Lenderman as team coach. Together they made history, bringing the Hamilton-Russell Cup back to the United States for the first time since 1937.

This victory was especially meaningful on the Saint Louis Chess Campus, which includes the CCSCSL and the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF). The CCSCSL hosts many elite tournaments, including the U.S., U.S. Women’s, U.S. Junior, and U.S. Girls’ Junior Chess Championships, along with tournaments like the Sinquefield Cup and Saint Louis Rapid & Blitz that bring in the top talent from around the country and the world. This is part of an effort to promote chess in the United States and provide opportunities for the best American players to compete on a global scale.

Global Moves features Olympiad artifacts from our own collection as well as materials from over 20 lenders and donors, among them inductees to the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame. Many of these treasures have never been exhibited at the WCHOF. The organization of Global Moves has resulted in several new donations to the WCHOF, including artifacts from the collections of Grandmasters Arthur Bisguier and Isaac Kashdan as well as Jacqueline Piatigorsky and Dorothy Teasley’s medals from Women’s Chess Olympiads. We have also taken this opportunity to have one of the highlights of our collection, a suite of furniture from the 1966 Havana, Cuba, Chess Olympiad, conserved, restoring a beautiful piece of chess history. Off view since the WCHOF relocated to Saint Louis from Miami, we are proud to present it along with a video from the 1966 Olympiad, showing tables from the tournament in use. The exhibition also includes a video produced for the exhibition featuring interviews with the American team from the 2016 Olympiad and several commentators who have participated in Chess Olympiads or Women’s Chess Olympiads themselves. Longer excerpts of these interviews are also included in this brochure, along with an essay by GM Lubomir Kavalek, a member of the gold medal-winning 1976 Olympiad team. It is our hope that through presenting these materials, Global Moves honors the rich legacy—and bright future—of the American chess.

—Emily Allred, Assistant Curator, World Chess Hall of Fame

Chess Gold Rush

Winning team gold at Chess Olympiads can be elusive. The Russians have not done it since 2002, and in the 90-year history of these competitions, Americans have won it only six times. Four of those triumphs came before World War II. Only U.S. Chess Champion Frank Marshall played on all four teams, earning four team gold medals. Three times the U.S. victories were in jeopardy on the last day of play, and only luck helped to clinch the gold.

2016 BAKU, AZERBAIJAN:

In the most recent Olympiad in Baku, the Americans fielded an incredibly strong team. Three members—Grandmasters Fabiano Caruana, Hikaru Nakamura and Wesley So—were rated among the top 10 players in the world. But in the last round Grandmaster Sam Shankland lost his game, and the gold medals were up for grabs. Nothing could be done because under a strange tiebreaking system the gold medals were hanging on a game from the match Estonia-Germany. Tarvo Seeman had a draw in hand that would have given the overall victory to Ukraine, but he did not see it and the U.S. team could celebrate. It was a great success: 175 countries registered to play in Baku and among the contenders, only Armenia, the winners from 2006, 2008 and 2012, did not take part.

1933 FOLKESTONE, ENGLAND:

Before World War II, when the Americans were a dominant force, not more than 20 teams participated in the Olympiads in which they competed. In the 1933 Folkestone Olympiad the strong U.S. team of Isaac Kashdan, Frank Marshall, Reuben Fine, Arthur Dake and native Albert Simonson was coasting toward first place. They could have even lost in the last round to their main rival, the Czechoslovakian team, with the score of 1-3 and still managed earn the gold. Everything went wrong early in the match. Around move 17, Kashdan, Fine, and Simonson were already utterly outplayed, and Frank Marshall could only hope for a draw. A loss of ½-3 ½ was very possible. The gold could have disappeared right there, but their fortunes changed on a dime. Fine’s opponent Josef Rejfir did not see the winning double-piece sacrifice and Fine escaped. Marshall exploited Karel Treybal’s mistake and turned a draw into a win. Although the Americans lost the match against the Czechs 1 ½ – 2 ½ , the overall victory was secured.

1976 HAIFA, ISRAEL:

The Olympiad in Haifa in 1976 was played for the first time under the Swiss pairing system with 46 teams competing in 13 rounds. As in Dubrovnik, Yugoslavia, in 1950, the Soviets and its communist allies stayed home. It was my third Olympiad with the U.S. team.

A story similar to Folkestone played out during the match of two contenders, the U.S and the Dutch teams. Robert Byrne quickly lost to Jan Timman and just before the time control Jim Tarjan blundered against Jan Hein Donner. I pressed too hard against Genna Sosonko and adjourned in a hopeless position. William Lombardy could not hope for more than a half point. We were looking at an embarrassing ½-3 ½ defeat, but like our predecessors in Folkestone, we turned it around. Hans Ree resisted Lombardy’s pressure for 60 moves, but his next move was a blunder and he lost. Sosonko was on his way to victory, but fumbled on move 71. My h-pawn sprinted fast and secured a draw. It was our trademark in Haifa to score much better than expected in the adjournments. We tallied 6 ½ points more than we should have objectively gained. Bill Goichberg was the U.S. team captain and Pal Benko was the team analyst. The match was played in the first half and we quickly fell behind the Dutch team. With three rounds to go, we were still 2 ½ points behind them.

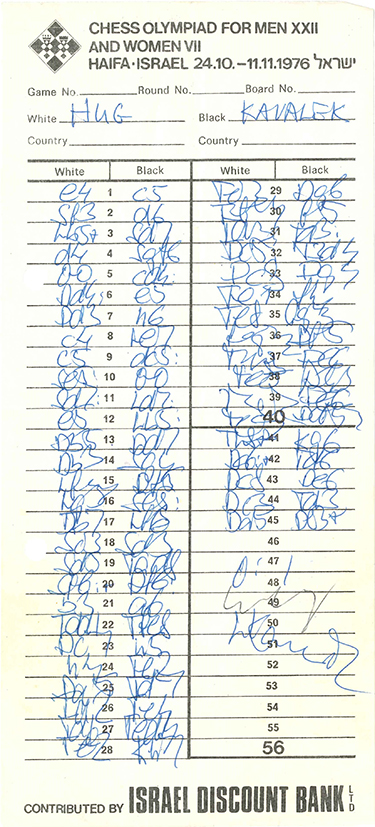

Bad form is an uninvited guest at the Olympiads and could be unpredictable. Tarjan and I struggled in Haifa and had the worst results on the team, but two years later in Buenos Aires, Argentina, we were the best performers. Tarjan ended his Olympiad career as one of the most successful American players with two gold and one silver individual medals. I finished in Haifa on a high note, winning the last two games, although I missed a queen sacrifice against Werner Hug, precisely the one that won World Chess Champion Magnus Carlsen the 2016 World Chess Championship match against Sergey Karjakin in New York.

We caught the Dutch team just in time before the last round started. The veterans Byrne, Larry Evans and Lombardy performed well throughout the event and won their last games against Wales. But our best performer Kim Commons misplayed his advantage and was in trouble. Did his opponent seal a winning move?

Commons’ opponent John Cooper was fighting for an individual board prize in Haifa. A win was important to him, but he did not seal the best move. Surprised by Commons’ reply, he ran into time trouble and offered a draw. The U.S. team was done but could not control who would win the gold medals.

The fate of those medals was in the hands of Ilkka Saren, a relatively unknown chess master from Finland. His Dutch opponent, Frans Kuijpers, had to win the game to secure the top spot for his team. It was the last game of the event, and it went on for hours with no end in sight.

Nervous chess players were pacing back and forth in the reception hall of the Dan Carmel Hotel, where the event was played. Occasionally, somebody came from the tournament hall to confirm that nothing dramatic had happened. On move 70, Kuijpers moved a pawn, a sign he wanted to prolong the marathon game by another 50 moves. Did he want to wear Saren down?

We admired the stoical look on Saren’s face. Where did it come from? We did not know that in the last championship of his country Saren fought for 159 moves. Equally, we were not aware why Kuijpers did not trying to break on the kingside. It was risky, but it was his only winning attempt. Only later did we learn that he made a similar risky bid the previous December in a team match against England and got burned. There they were, two players moving back and forth, caught in their past. After 111 moves and 14 ½ hours they agreed to a draw and we won the gold, and the Dutch got the silver.

In the report for the Dutch magazine Schaakbuletin, Jan Hein Donner wrote: “The Americans humiliated us once more before departure when they declined to carry the Hamilton-Russell cup with them and the Dutch–the irony of it all–ended up having to drag the thing with them to Amsterdam to be deposited with FIDE in their offices.”

In 1968, I was nominated to play the top board for Czechoslovakia at the Olympiad in Lugano, Switzerland, but after the Soviet-led invasion of my native country, I escaped to the West. I could not have predicted that I would end up playing for the United States in seven Olympiads, three times on the top board, twice on the second, winning one gold and five bronze team medals. Only after my professional chess career was over, did I realize that with the help of 19 different teammates I won six Olympiad team medals, the most by any American player since 1928.

—GM Lubomir Kavalek

London, England

Nayler Brothers

Hamilton-Russell Cup

1927

19 x 12 ½ x 8 ½ in.

Gilt silver and mahogany

Collection of the Fédération Internationale des Échecs

Created in 1927 and presented to the World Chess Federation (Fédération Internationale des Échecs or FIDE) by Frederick Gustavus Hamilton-Russell, this trophy celebrates the accomplishments of the winning teams in the open section of the Chess Olympiad. Teams from around the world compete in the biennial tournament, and the first-place team takes custody of this trophy until the next Olympiad. The trophy’s base displays the names of the winning teams. The Hamilton-Russell Cup is currently in the care of the World Chess Hall of Fame and US Chess due to the victory of the American team in the open section of the 2016 Chess Olympiad, which was held in Baku, Azerbaijan, from September 1 to 14, 2016. The American team included Grandmasters Fabiano Caruana, Hikaru Nakamura, Ray Robson, Sam Shankland, and Wesley So. International Master John Donaldson served as team captain and Grandmaster Aleksandr Lenderman served as team coach. Caruana, Nakamura, and So participated in the 2017 Grand Chess Tour.

1930s

Grandmaster Frank Marshall’s Commemorative Medal from the 1931 Prague, Czechoslovakia (present-day Czech Republic), Chess Olympiad

1931

2 1⁄8 in.

Metal

Collection of the Marshall Chess Club

Adorned with a view of Prague, U.S. Chess Champion Frank Marshall received this commemorative medal while representing the United States in the fourth Chess Olympiad. At the top is an image of St. Vitus Cathedral, a gothic structure that is a landmark in the city. After the American team’s victory, Marshall brought the Hamilton-Russell Cup, the perpetual trophy for the Chess Olympiads, back to the United States. On August 13, 1931, Hermann Helms reported on his return, noting that, “The Marshall Chess Club, which bears his name, will send a large delegation which will escort him in triumph to the club’s headquarters at 135 W. 12th St., Manhattan.” Helms went on to note that the Americans had been able to triumph despite International Master (IM) Al Horowitz breaking his collarbone after jumping off a car, leaving him to play “his last four games with his right arm in a sling.”

Grandmaster Frank Marshall’s Cigarette Case from the 1935 Warsaw, Poland, Chess Olympiad

1935

3⁄8 x 4 ¼ x 3in.

Silver

Collection of the Marshall Chess Club

In 1935, the United States won the Chess Olympiad for the third time in a row. Grandmaster Frank Marshall received this cigarette case as a prize in the Olympiad, as indicated by its inscription. Marshall was the longest reigning U.S. Chess Champion, holding the title from 1909 to 1936, and the founder of the long-running Marshall Chess Club. He also captained the four gold medal-winning American Olympiad teams of the 1930s. A September 2, 1935, New York Times article about the 1935 victory stated, “Marshall modestly acknowledged the great honor which once more had come to his country where, he added, great satisfaction was felt in this new triumph by his team.”

Jerzy Steifer

Reproduction of a Pin from the 1935 Warsaw, Poland, Chess Olympiad

2011

1 x 5⁄8 in.

Pin

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

This pin reproduces the logo of the 1935 Warsaw, Poland, Chess Olympiad, with two knights flanking a tower. Jerzy Steifer, an amateur artist, created the distinctive design. Steifer served in the Polish Navy and died during the Battle of Kock in 1939, when the Germans invaded Poland. During this Olympiad, Grandmaster Arthur Dake played every game except one—the round against the Polish team—in deference to his father’s history as an immigrant from that country.

Photographer unknown

United States Team with Fritz Brieger at the 1937 Stockholm, Sweden, Chess Olympiad

1937

2 9⁄16 x 2 1⁄8 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Richard Kashdan

Pictured from left to right: GM Samuel Reshevsky, IM Al Horowitz, Fritz Brieger (Sponsor), GM Frank Marshall, GM Reuben Fine, and GM Isaac Kashdan

1937 marked both the last year the United States would win team gold in the 1930s and the debut of former chess prodigy Grandmaster (GM) Samuel Reshevsky in the competition. Reshevsky, who immigrated to the United States from Poland in 1920, had only returned to competitive chess in 1933 after leaving it to focus on his education. In his childhood, he had earned fame across the country for his performance in simultaneous matches, emerging victorious against opponents who were much older than him. One of his early supporters, GM Frank Marshall, was also on the team. Marshall and International Master Al Horowitz ended the competition undefeated. Unfortunately, this would be the last time the United States participated in the competition before World War II. In 1939, Buenos Aires, Argentina, hosted the Chess Olympiad, the American team was not able to attend due to funding issues. The competition would then go on hiatus during the entirety of World War II, and the United States would not win team gold again until 1976.

1950s & 60s

Organization of the Chess Olympiads was suspended during World War II and the following years. In 1950, they restarted, and the landscape in the chess community had changed. On the global level, some players who had been the most prominent in the era before the war, such as World Chess Champions Alexander Alekhine and José Raúl Capablanca and U.S. Chess Champion Frank Marshall, had passed away before the Olympiads resumed. Others such as Dawid Przepiórka died in the Holocaust. Some, like Grandmaster Miguel Najdorf, became refugees and settled in new countries. In the United States, some players including Isaac Kashdan had largely left competitive chess due to diminished opportunities to play and needed to support their families. The Soviet Union began competing in Olympiads in 1952, establishing an era of dominance in the competition that would last until 1990. In the 1950s and 1960s, competition between the United States and the Soviet Union was often influenced by the tensions of the Cold War. 1957 also marked the organization of the first Women’s Chess Olympiad.

Chess Table from the 1966 Havana, Cuba, Chess Olympiad

1966

Chairs: 33 x 22 x 18 in.

Table: 30 x 45 x 36 in.

Board: 7⁄8 x 19 ½ x 19 ½ in.

Wood, leather, fabric, and marble

Collection of the U.S. Chess Trust

Created for the 1966 Havana, Cuba, Chess Olympiad, this table and chairs is one of the highlights of this exhibition. The table has multiple features designed for the comfort of players, including leather armrests and spaces to store belongings. The Havana organizers made special efforts to make this one of the best Olympiads in history. In a December 1966 article in Chess Life, U.S. team member Larry Evans noted that it was the “biggest, best organized, and best run to date” and that organizers reportedly spent 1.3 million pesos on the event. It is unknown how many tables were made, but International Master (IM) John Donaldson has estimated 104-120. Since the tables were used continuously throughout the tournament, it is impossible to tell which players competed at specific tables. After the Olympiad ended, organizers sent tables to Board One players and important FIDE (Fédération Internationale des Échecs or World Chess Federation) officials around the world. Fred Cramer, then Zonal President for the United States, received this one. The table has replica flags, chess pieces, and name placards. The chess set displays a position from Grandmaster Bobby Fischer’s 1966 Olympiad game against IM Jacek Bednarski, which Fischer included in his book My 60 Memorable Games (1969).

Postcard from the 1950 Dubrovnik, Yugoslavia (present-day Croatia), Chess Olympiad

August 1950

5 ½ x 3 5⁄8 in.

Postcard

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Jacqueline Piatigorsky’s Individual Medal from the 1957 Emmen, the Netherlands, Chess Olympiad

1957

Medal: 1 9⁄16 in.

Metal

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Joram Piatigorsky

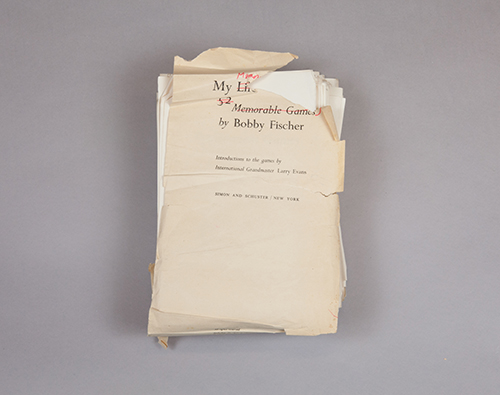

Bobby Fischer and Larry Evans

Draft of My 60 Memorable Games with Editing Notes

1966

Simon and Schuster

8 3/4 x 5 9⁄16 in.

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

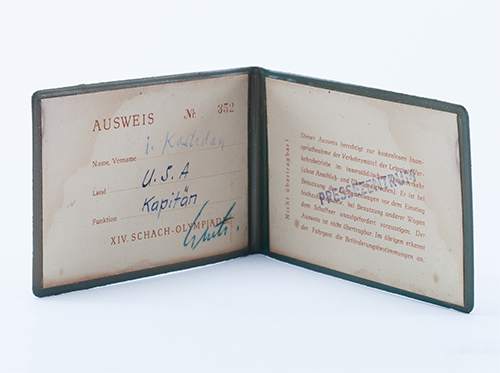

GM Isaac Kashdan’s Tournament Hall Pass from the 1960 Leipzig, Germany, Chess Olympiad

1960

2 ½ x 7 5⁄16 in.

Hall pass

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Richard Kashdan

Five Stamps from the 1966 Havana, Cuba, Chess Olympiad

1966

1 ¾ x 1 1⁄8 in.

Lithograph printed stamps

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

FIDE

FM Nathan Divinsky’s Press Badge from the 1966 Havana, Cuba, Chess Olympiad

October 23-November 20, 1966

2 1⁄8 x 1 7⁄8 in.

Metal pin

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Judy Kornfeld

GM Isaac Kashdan’s Commemorative Medal from the 1960 Leipzig, East Germany (present-day Germany), Chess Olympiad

1960

Medal: 2 7⁄16 x 3 3⁄8 in.

Box: 3 ¾ x 4 ¼ in.

Metal

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Richard Kashdan

Chess Life, Vol. 21, No. 11

November 1966

11 x 8 ½ in.

Magazine

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

Pictured left to right: GM Larry Evans, IM William Addison, GM Pal Benko, GM Bobby Fischer, GM Nicholas Rossolimo, GM Robert Byrne, and team captain IM Donald Byrne

1970s & 80s

The 1970s and 1980s marked a moment of transition for American Chess Olympiad teams. New talent from the Soviet Union and Soviet bloc countries, including Woman Grandmaster Anna Gulko (Akhshuramova), Grandmaster (GM) Boris Gulko, and GM Lubomir Kavalek, joined teams that included both legends of the 1950s and 1960s and rising American players like GM Walter Browne, Woman International Master (WIM) Diane Savereide, and GM Yasser Seirawan. In 1972, the Women’s Chess Olympiad began to be held at the same time as the Open (or at that time, Men’s) Olympiad. This exhibition contains artifacts related to several Olympiads of the 1970s and 1980s, as well as medals won by the American team during this period.

Envelope from the 1970 Siegen, West Germany (present-day Germany), Chess Olympiad

1970

3 5⁄8 x 6 7⁄16 in.

Paper

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Richard Kashdan

Bertoni S.R.L. Milano

GM Lubomir Kavalek’s Participation Medal from the 1972 Skopje, Yugoslavia (present-day Republic of Macedonia), Chess Olympiad

1972

Medals: 2 1⁄8 in. dia.

Stand: 4 ½ x 6 ¼ in.

Metal and velvet

Collection of Lubomir Kavalek

Grandmaster (GM) Lubomir Kavalek played in nine Olympiads—two for his native Czechoslovakia and the last seven for the United States. He made his first appearance as an American in 1972, when interest in the game was high as a result of the recently concluded Bobby Fischer-Boris Spassky World Chess Championship match. American planners hoped to organize a team of the strongest American players, with World Chess Champion Fischer at its center, in order pose a serious challenge to the Soviet team, which had dominated the Olympiads since the 1950s. Initially, Coca-Cola agreed to provide $100,000 in sponsorship for the American team, but they had one condition—Fischer had to play. When he dropped out, the plan began to fall apart, and a number of the most talented American players (GMs Samuel Reshevsky, Larry Evans, Pal Benko and William Lombardy) declined to play. The result was the U.S. fielded one of its weakest ever teams and finished ninth. Despite this disappointment, Kavalek, who scored 11 ½ out of 18 on Board One, still impressed in his American debut. Every other American team he played for over the course of his career medaled.

Bertoni S.R.L. Milano

GM Walter Browne’s Participation Medals from the 1972 Skopje, Yugoslavia (present-day Republic of Macedonia), Chess Olympiad

1972

Medals: 2 1⁄16 in. dia.

Stand: 4 ½ x 6 ¼ in.

Metal and velvet

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Raquel Browne

Before representing the United States in the Chess Olympiad, GM Walter Browne twice competed on behalf of Australia, his mother’s native country. In 1972, Browne earned an individual bronze medal for his efforts. This medal is part of a donation of Browne’s archive, which Browne’s wife Raquel gifted to the World Chess Hall of Fame after his 2015 death.

Cartier

GM Lubomir Kavalek’s Bronze Medal from the 1974 Nice, France, Chess Olympiad

1974

1 7⁄8 in. dia.

Metal

Collection of Lubomir Kavalek

The U.S. sent a strong team to the Nice, France, Chess Olympiad. Headed by GM Lubomir Kavalek, the 10th-rated player on the May 1974 FIDE rating list, it also featured GM Robert Byrne, who placed third in the 1973 Leningrad Interzonal to qualify for the Candidates Matches. The team, led by Byrne’s score of 12 from 16, finished third. It was the first time the U.S. had medaled in eight years. Byrne holds the record for most games completed in the competition by an American—116 games.

Cartier

GM Jim Tarjan’s Team Bronze Medal from the 1974 Nice, France, Chess Olympiad

1974

1 7⁄8 in. dia.

Metal

Collection of Jim Tarjan

Signed First Day Cover from the 1974 Nice, France, Chess Olympiad

1974

3 5⁄8 x 6 7⁄16 in.

Envelope

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Richard Kashdan

Pin from the 1974 Nice, France, Chess Olympiad

1974

2 3⁄16 in. dia.

Plastic

Collection of Allan Savage

GM Isaac Kashdan’s Press Pass for the 1974 Nice, France, Chess Olympiad

1974

1 1⁄8 x 2 ¼ in.

Pin

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Richard Kashdan

WIM Ruth Haring’s Commemorative Medal from the 1976 Haifa, Israel, Chess Olympiad

1976

2 ¼ in. dia.

Metal

Collection of Ruth Haring

Woman International Master (WIM) Ruth Haring, one of two women to serve as president of the U.S. Chess Federation (now US Chess), represented her country in five Women’s Chess Olympiads from 1974 to 1982. Her best event was in 1976, when she scored 5 out of 8 as the reserve player to win an individual bronze medal and helped lead a balanced scoring American team (WIM Diane Savereide, WIM Rachel Crotto, and Ruth Herstein) to fourth place. This was the best result for American women until the 2000s. Before the tournament, United States Chess Federation Executive Director and 1995 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Ed Edmondson “expressed hope that their participation would help lure more women into the game, which has been dominated by men.”

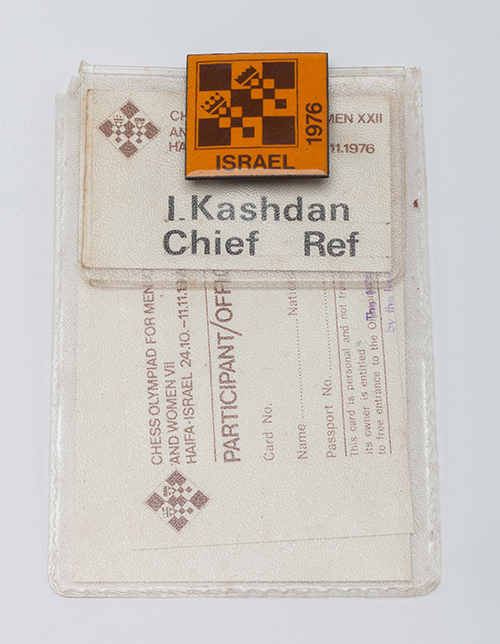

GM Isaac Kashdan’s Identity Card and Pin for the 1976 Haifa, Israel, Chess Olympiad

1976

Pin: 1 7⁄8 x 1 7⁄8 in.

Pass: 5 1⁄8 x 3 ½ in.

Laminated press pass and metal pin

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Richard Kashdan

Scoresheet from Round 9 of the 1976 Haifa, Israel, Chess Olympiad: GM Jim Tarjan vs. IM Leon Lederman

October 26-November 10, 1976

9 5⁄16 x 4 3⁄16 in.

Scoresheet

Collection of Jim Tarjan

Scoresheet from Round 11 of the 1976 Haifa, Israel, Chess Olympiad, IM Werner Hug vs. GM Lubomir Kavalek

October 24-November 11, 1976

9 1⁄8 x 4 3⁄16 in.

Scoresheet

Collection of Lubomir Kavalek

Keesing

Wim Andriessen, Jan Timman, Gennady Sosonko, Gert Ligterink, and Lubomir Kavalek

22e Schaakolympiade Haifa 1976

1977

8 ¼ x 5 5⁄8 in.

Book

Collection of Lubomir Kavalek

GM Jim Tarjan’s Medal for Highest Individual Score on 5th Board from the 1978 Buenos Aires, Chess Olympiad

1978

1 1⁄8 in. dia.

Metal

Collection of Jim Tarjan

The 23rd Chess Olympiad in Buenos Aires was a repeat of the success of 1974 for American reserve player GM Jim Tarjan, who scored 9 ½ from 11 to once again win individual gold and team bronze medals. Tarjan’s 5 ½ points from the last six rounds made the difference between an excellent and acceptable result for the U.S. team. His performance rating of 2709 was the second-highest of the Olympiad behind only the legendary player GM Viktor Korchnoi.

GM Jim Tarjan’s Team Bronze Medal from the 1978 Buenos Aires, Argentina, Chess Olympiad

1978

1 1⁄8 in. dia.

Metal

Collection of Jim Tarjan

GM Jim Tarjan was one of America’s best players during the 1970s and early 1980s. He represented the U.S. on five Olympiad teams during this era, winning four team and three individual medals. His Olympiad debut in Nice, France, was nothing short of sensational and a sign of things to come. Tarjan finished his Olympiad career with a lifetime winning percentage of 76 percent, which is among the highest ever achieved by an American who has played more than one event. His performance has only been exceeded by GMs Sam Shankland (81 percent) and Isaac Kashdan (80 percent).

GM Lubomir Kavalek’s Team Bronze Medal from the 1978 Buenos Aires, Argentina, Chess Olympiad

1978

1 1⁄8 in. dia.

Metal

Collection of Lubomir Kavalek

Born in Prague, Czechoslovakia, GM Lubomir Kavalek became the youngest player to win the Czech Championship at age 19 in 1962. He would repeat the feat again six years later. In 1970, he immigrated to the US, where he completed his studies in journalism and literature. During the 1970s, he won or tied for first in the U.S. Chess Championship three times and was rated in the world’s top 100 players continuously from 1962 to 1988. A veteran of nine Olympiads, Kavalek represented Czechoslovakia twice and the U.S. seven times. He also won more than 20 important tournaments over the course of his career. Today, Kavalek is the chess columnist for the Huffington Post.

WIM Dorothy Teasley’s Commemorative Medal from the 1978 Buenos Aires, Argentina, Chess Olympiad

1978

1 1⁄8 in. dia.

Metal

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Dorothy Teasley

WIM Dorothy (Dolly) Teasley is one of only eight American women to have won individual medals in Chess Olympiads. She scored 7 ½ from 10 to win a bronze medal as the third best reserve player in 1978. A five-time competitor in the U.S. Women’s Chess Championship, Teasley fondly remembers the 1978 Buenos Aires, Argentina, Chess Olympiad, and upon donating this medal to the World Chess Hall of Fame, related a story of that year’s team captain, International Master (IM) Anthony Saidy. She stated, “Dr. Saidy was given a $1000 emolument [fee] from the USCF [today US Chess]. What did he do with it? He split it five equal ways amongst the four team members and himself. We all received an unexpected windfall of $200 (equivalent to about $778 today). It was a princely gift.” In an article for Chess Life about the Olympiad, Saidy interviewed the reigning Women’s World Chess Champion, Maya Chiburdanidze, who is from the country of Georgia, which is renowned for its number of extraordinary female players. He humorously stated that the reason Georgia produced these players was not something “in the yogurt” there; rather, it was the support and training offered to young female players. He suggested that the United States follow suit to develop its young talents.

International Braille Chess Association Michael Garner’s Silver Medal from the 1980 Noordwijkerhout, Netherlands, Blind Chess Olympiad

1980

1 ½ in. dia.

Metal

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Michael Garner won this silver medal for his performance in the second Blind Chess Olympiad. The competition has been held since 1961 and is organized by the International Braille Chess Association, a group that supports players who have visual impairments. Only eight teams competed in the first Blind Chess Olympiad, but the tournament has grown slowly since.

GM Yasser Seirawan’s Silver Medal from the 1980 Valletta, Malta, Chess Olympiad

1980

1 5⁄8 in. dia.

Metal

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Yasser Seirawan

Four-time U.S. Chess Champion Yasser Seirawan represented the U.S. in 10 Olympiads between 1980 and 2002, and his lifetime winning percentage of 65 percent is particularly impressive considering he played most events on Board One or Two.

The 1980 Olympiad was Seirawan’s debut. He did well, winning the silver medal on Board Two and defeating former World Chess Champion Mikhail Tal—the first of four games he would win against the player nicknamed the “Wizard of Riga.”

GM Jim Tarjan’s Individual Bronze Medal for 3rd Best Score on 5th Board from the 1982 Lucerne, Switzerland, Chess Olympiad

1982

1 ¼ in. dia.

Metal

Collection of Jim Tarjan

GM Jim Tarjan often led the U.S. teams that took home bronze medals five times between 1974 and 1986. In the 1982 Lucerne, Switzerland, Chess Olympiad—his final appearance in the competition—he won an individual bronze along with the team medal by scoring 7 from 9 for a 2688 rating performance.

GM Jim Tarjan’s Team Bronze Medal from the 1982 Lucerne, Switzerland, Chess Olympiad

1982

2 13⁄16 x 1 9⁄16 in.

Metal and ribbon

Collection of Jim Tarjan

The Swiss city of Lucerne organized the 1982 Chess Olympiad in impeccable style. Unlike most Olympiads, the United States entered this event as one of the favorites, seeded second a point ahead of Hungary. The surprise of the event was Czechoslovakia, which finished second, the first time it had medaled since 1933.

GM Lubomir Kavalek’s Team Bronze Medal from the 1982 Lucerne, Switzerland, Chess Olympiad

1982

2 13⁄16 x 1 9⁄16 in.

Metal and ribbon

Collection of Lubomir Kavalek

Bill Hook

GMs Walter Browne and Lubomir Kavalek at the 1982 Lucerne, Switzerland, Chess Olympiad

1982

3 ½ x 4 2⁄5 in.

Photograph

Collection of Lubomir Kavalek

GM Lubomir Kavalek’s Commemorative Bronze Medal from the 1984 Thessaloniki, Greece, Chess Olympiad

1984

1 15⁄16 in. dia.

Metal and ribbon

Collection of Lubomir Kavalek

The Soviet Union, which often fielded a lineup of six of the best players in the world, was by far the most difficult opponent for American teams between 1952 and 1990. The Sovies were dominant in the competition—in 18 matches they scored 14 match victories and two draws against only two defeats. US. teams of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s suffered, but the matches became much more competitive in the 1980s with the Americans winning in 1984 and 1986. The heroes in 1984 were GMs Nick de Firmian and Roman Dzindzichashvili. The latter played only one Olympiad, but he had a great performance, as he scored 8 out of 11 on Board One to lead the U.S. to third place.

GM Walter Browne’s Commemorative Bronze Medal from the 1984 Thessaloniki, Greece, Chess Olympiad

1984

1 15⁄16 in. dia.

Metal

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Raquel Browne

Team Bronze Medal from the 1986 Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Chess Olympiad

1986

3 ¾ x 2 in.

Metal and ribbon

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

The fifth-seeded United States team of GMs Yasser Seirawan, Larry Christiansen, Lubomir Kavalek, John Fedorowicz, Nick de Firmian, and Maxim Dlugy performed tremendously in the 1986 Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Chess Olympiad. They led for most of the event after defeating perennial favorites Hungary and the Soviet Union. After 13 rounds, the Americans had won 11 matches, drawn one, and lost one, to lead with 36 ½ game points, to the Soviet Union’s 36 and England’s 35 ½. Unfortunately for the U.S., in the last round both its rivals went 4-0, while it could only draw 2-2 against Bulgaria. It would have been a tremendous upset if the Americans had been able to win gold since the Soviets outrated the American team by an average of 126 rating points per board.

Chess Life Vol. 42, No. 3

March 1987

10 5⁄8 x 8 ¼ in.

Magazine

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

Bill Hook

GMs Lajos Portisch and Lubomir Kavalek at the 1984 Thessaloniki, Greece, Chess Olympiad

1984

4 x 6 in.

Photograph

Collection of Lubomir Kavalek

Stamp from the 1978 Buenos Aires, Argentina, Chess Olympiad

1978

1 3⁄8 x 1 ¾ in.

Stamp

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Bill Hook

GM Larry Christiansen vs. GM Jóhann Hjartarson at the 1986 Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Chess Olympiad

1986

3 15⁄16 x 5 7⁄8 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Trust

Grandmaster Larry Christiansen is a three-time U.S. Champion, who has represented his country in nine Chess Olympiads and won five team medals. Christiansen won the game against GM Hjartarson, leading the United States to a 3-1 victory over a strong Icelandic team.

Bill Hook

WGM Anna Akhsharumova and WGM Diane Savereide at the 1988 Thessaloniki, Greece, Chess Olympiad

1988

4 x 5 13⁄16 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Trust

1988 marked an important milestone in American chess. For the first time, the United States fielded an all-master team headed by top boards Woman Grandmaster Anna Akhsharumova and six-time U.S. Women’s Chess Champion Diane Savereide. Savereide was the dominant U.S. women’s player through the 1970s and 1980s, and only the second American woman to achieve a master’s rating; as such, she inspired a new generation of American women chess players. The team drew matches against top seeds China, Soviet Union, and Yugoslavia, losing only to a Hungarian team led by Grandmaster Susan Polgar, to finish ninth.

Bill Hook

GM Yasser Seirawan vs. GM Garry Kasparov as GM Anatoly Karpov Watches at the 1988 Thessaloniki, Greece, Chess Olympiad

1988

4 x 5 ¾ in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Trust

Four-time U.S. Chess Champion Yasser Seirawan and World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov of the Soviet Union, who compete before an attentive group of spectators in this photograph, traded individual wins and team victories in 1986 and 1988. Seirawan and the U.S. team won in 1986 in the Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Chess Olympiad by a score of 2 ½-1 ½. Two years later, Kasparov and the Soviets got their revenge by an identical margin.

Bill Hook

U.S. Team Competes against the Soviet Team at the 1988 Thessaloniki, Greece, Chess Olympiad

1988

4 x 5 13⁄16 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Trust

Pictured from foreground to background: GM Nick de Firmian vs. Alexander Beliavsky; GM Joel Benjamin vs. Artur Yusupov; GM Boris Gulko vs. GM Anatoly Karpov; GM Yasser Seirawan vs. GM Garry Kasparov

Pictured in the foreground of this photograph, American Grandmasters Joel Benjamin and Nick de Firmian competed on six and eight U.S. Olympiad teams respectively. Benjamin is a winner or co-winner of virtually every major U.S. title, including six World Opens and three U.S. Opens. He has competed in a record 23 consecutive U.S. Chess Championships, winning three (1987, 1997, 2000). Benjamin also served as the official grandmaster consultant for IBM’s Deep Blue computer, which in 1997 claimed a historic victory over World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov, who also appears in this photograph. De Firmian is a three-time U.S. chess champion (1987, 1995, 1998).

1990s

The well-balanced teams of the 1990s featured many players of similar strength. American teams twice won silver medals and one took bronze in the open section in the 1990s.

Postcard from the 1990 Novi Sad, Yugoslavia (present-day Serbia), Chess Olympiad

1990

4 1⁄8 x 6 1⁄8 in.

Postcard

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Commemorative Medal from the 1990, Novi Sad, Yugoslavia (present-day Serbia), Chess Olympiad

1990

Medal: 2 ¼ in.

Case: 4 ¾ x 3 ¾ in.

Metal

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam

Ceramic Knight from the 1990, Novi Sad, Yugoslavia (present-day Serbia), Chess Olympiad

1990

7 ½ x 4 ½ in.

Ceramic

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

GM Yasser Seirawan’s Individual Medal for Best Result on Board 4 from the 1994 Moscow, Russia, Chess Olympiad

1994

Medal: 2 in.

Ribbon: 14 ½ in.

Metal and ribbon

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Third Place Trophy from the 1996 Yerevan, Armenia, Chess Olympiad

1996

13 ¾ x 3 ¼ in.

Trophy

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis

Team Bronze Medal from the 1996 Yerevan, Armenia, Chess Olympiad

1996

2 ½ in.

Metal

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Team Bronze Medal from the 1996 Yerevan, Armenia, Chess Olympiad

1996

2 ½ in.

Metal

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

GM Yasser Seirawan’s Team Silver Medal from the 1998 Elista, Russia, Chess Olympiad

1998

Medal: 2 1⁄8 in.

Ribbon: 14 ½ in.

Metal and ribbon

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Bill Hook

GM Gata Kamsky at the 1992 Manila, Philippines, Chess Olympiad

1992

5 15⁄16 x 4 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Trust

Grandmaster Gata Kamsky, who made his Olympiad debut for the U.S. at the age of 18, is American chess legend. A five-time U.S. Chess Champion and 2016 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame Inductee, he has represented the U.S. in six Olympiads and three World Team Championships, including 1993 when he was the first board on a team which took first place. He is the only American since World Chess Champion Bobby Fischer to play a match for the World Chess Championship.

Bill Hook

GM Boris Gulko at the 1990 Novi Sad, Yugoslavia (present-day Serbia), Chess Olympiad

1990

5 13⁄16 x 4 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the U.S. Chess Trust

Grandmaster (GM) Boris Gulko, the only player to win both the Soviet and U.S. Chess Championships, shares with GMs Yasser Seirawan, Larry Christiansen, and Alex Onischuk the honor of representing the U.S. most times in team competitions (Olympiads and World Team Championships) with 12. Gulko earned two Olympiad team medals playing for the United States and another for representing the Soviet Union in 1978. The son of a Red Army soldier, Boris Gulko was born in East Germany in the years after World War II. He returned to the Soviet Union as a young child and lived there until the mid-1980s, when he immigrated to the United States. While in the Soviet Union, he won the U.S.S.R. Chess Championship in 1977, a year after attaining GM status. Shortly afterward, Gulko—a staunch anti-communist—and his wife, Anna, were denied permission to leave the country. Gulko himself was once arrested and beaten by KGB agents, and following their failed petition, both he and Anna, who held the title of woman grandmaster, were banned from chess competition until 1986, when they arrived in the United States. While he called his years away from the game “a serious blow” to his career, he found success in his new country, winning the U.S. Chess Championship in 1994 and 1999.

2000s

GM Yasser Seirawan’s Silver Medal for the Second Best Result on Board 2 at the 2002 Bled, Slovenia, Chess Olympiad

2002

Medal: 3 1⁄8 in.

Ribbon: 19 in.

Glass and ribbon

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

WGM Jennifer Shahade’s Team Silver Medal from the 2004 Calvià, Majorca, Spain, Chess Olympiad

2004

Medal: 2 11⁄16 in. dia.

Box: 3 ¾ x 4 x 1 1⁄8 in.

Metal and velvet

Collection of Jennifer Shahade

GM Susan Polgar’s Gold Medal for the Best Individual Result of the 2004 Calvià, Majorca, Spain, Chess Olympiad

2004

Medal: 2 11⁄16 in. dia.

Box: 5 x 5 x 1 ½ in.

Metal and velvet

Collection of Grandmaster Susan Polgar

GM Susan Polgar’s Team Silver Medal from the 2004 Calvià, Majorca, Spain, Chess Olympiad

2004

Medal: 2 11⁄16 in. dia.

Box: 3 ¾ x 4 x 1 1⁄8 in.

Metal and velvet

Collection of Grandmaster Susan Polgar

WGM Rusudan Goletiani’s Individual 2nd Place Medal on Board 3 from the 2008 Dresden, Germany, Chess Olympiad

2008

1 1⁄8 x 3 7⁄16 x 2 7⁄16 in.

Glass

Collection of Rusudan Goletiani

WGM Rusudan Goletiani’s Team Bronze Medal from the 2008 Dresden, Germany, Chess Olympiad

2008

3 x 2 x 2 inches.

Glass

Collection of Rusudan Goletiani

WGM Tatev Abrahamyan’s Team Bronze Medal from the 2008 Dresden, Germany, Chess Olympiad

2008

3 x 2 x 2 in.

Glass

Collection of Tatev Abrahamyan

Pin from the 2008 Dresden, Germany, Chess Olympiad

2008

1 3⁄16 x 11⁄16 in.

Pin

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Bill Hook

GM Gregory Kaidanov (USA) and GM Yasser Seirawan (USA) at the 2002 Bled, Slovenia, Chess Olympiad

2002

4 x 6 in.

Photograph

Collection of Lubomir Kavalek

Bill Hook

Tournament Play at the 2002 Bled, Slovenia, Chess Olympiad

2002

4 x 6 in.

Photograph

Collection of Lubomir Kavalek

The 2016 Olympiad

This case contains a number of artifacts related to the 2016 gold medal victory of the American team. Some are part of the collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, while others are loans from the players themselves. The historic win was the first since 1976 and the first time the U.S. had won in an Olympiad in which a Russian or Soviet team had competed. The U.S. team included three of the top 10 players in the world: Grandmasters (GMs) Fabiano Caruana, Hikaru Nakamura, and Wesley So. The team also included GMs Sam Shankland and Ray Robson. Of the win, Nakamura said, “It all felt very very smooth from start to finish and I think that’s probably the strangest thing about it. Normally nothing seems to be that smooth in life and the Olympiad just seemed to be very smooth. It was actually quite enjoyable for that reason. There wasn’t the stress or any of the emotions involved.”

GM Wesley So’s Team Gold Medal from the 2016 Baku, Azerbaijan, Chess Olympiad

2016

Medal: 2 3⁄8 in. dia.

Ribbon: 19 ¼ in.

Metal and ribbon

Collection of Grandmaster Wesley So

GM Wesley So’s Individual Gold Medal on Board 3 from the 2016 Baku, Azerbaijan, Chess Olympiad

2016

Medal: 2 3⁄8 in. dia.

Ribbon: 19 ¼ in.

Metal and ribbon

Collection of Grandmaster Wesley So

GM Ray Robson’s Team Gold Medal from the 2016, Baku, Azerbaijan, Chess Olympiad

2016

Medal: 2 5⁄16 in.

Ribbon: 17 ¼ in.

Metal and ribbon

Collection of Ray Robson

IM John Donaldson’s Team Gold Medal from the 2016, Baku, Azerbaijan, Chess Olympiad

2016

Medal: 2 5⁄16 in.

Ribbon: 17 ¼ in.

Box: 7 5⁄8 x 6 13⁄16 x 7 5⁄8 in.

Metal, ribbon, and wood

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

GM Aleksandr Lenderman’s Papaq from the 2016 Baku, Azerbaijan, Chess Olympiad

2016

4 1/2 x 8 in. dia.

Wool

Collection of Alexsandr Lenderman

Scoresheet from Round 5 of the 2016 Baku, Azerbaijan, Chess Olympiad: GM Nikola Sedlak vs. GM Wesley So

September 6, 2016

10 3⁄8 x 6 7⁄8 in.

Score sheet

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

GM Wesley So’s Watch from the 2016 Baku, Azerbaijan, Chess Olympiad

2016

Watch face: 1 ½ in.

Box: 3 1⁄16 x 3 3⁄8 x 2 5⁄8 in.

Leather, stainless steel, and mineral crystal

Collection of Grandmaster Wesley So

Entrance Tickets from the Closing Ceremony of the 2016 Baku, Azerbaijan, Chess Olympiad

September 13, 2016

7 ¾ x 3 7⁄8 in.

Paper

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Mike Klein

Press

2/22/18: St. Louis Public Radio — On Chess: Reliving American chess victory on the world stage

11/13/2017: HEC TV — Exhibit Honors U.S. Team’s First Chess Olympiad Victory in 40 Years (video)

11/10/2017: River Front Times — The Best Things to Do in St. Louis This Week, November 10-15

11/9/2017: St. Louis Public Radio — On Chess: The history of the United States in Chess Olympiads

11/8/2017: Chess 24 — Carlsen & Ding Liren in Champions Showdown

10/25/2017: Global Moves: Americans in Chess Olympiads Exhibition Press Release