Chess Masterpieces: Highlights from the Dr. George & Vivian Dean Collection (September 9, 2011-February 12, 2012) was one of the World Chess Hall of Fame’s (WCHOF) inaugural exhibitions. This new exhibition of works from the Dean collection marks the WCHOF’s fifth anniversary as well as Dr. George andVivian Dean’s 55th year of collecting fine chess sets.

Lovers of history and art, the Deans have traveled to over 100 countries to find over 1,000 of the finest chess sets from the 8th century CE to the present, and have assembled them into one of the world’s most distinguished private collections.

However, the Deans are also passionate about science. Dr. Dean is a physician as was Carl Linnaeus, who in his 1735 book Systema Naturae proposed the first comprehensive system of classifying the entire natural world into animal, vegetable, and mineral kingdoms. The selection of these chess sets is based on the categories of Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae. Their presentation is inspired by another influential Age of Enlightenment text, Denis Diderot’s Encyclopaedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts, (1751-1772). By exhibiting chess sets (Arts) in the context of the natural materials (Sciences) from which they were made along with examples of the types of tools and processes used to make them (Crafts) it becomes evident that chess sets and chess culture are not apart from life, but a part of life and the natural world that surrounds us.

On View: September 29, 2016 – March 12, 2017

The Chess Collection of Dr. George & Vivian Dean

This exhibition commemorates the 55th year that Dr. George and Vivian Dean have collected chess sets together. They purchased their first chess set in the Middle East and thereafter acquired a set in each country they visited. As they immersed themselves in chess history and joined a worldwide community of chess set connoisseurs, they expanded their collection more systematically. Now they travel to new countries for the sole purpose of acquiring new sets to make the collection more comprehensive. Their collection includes over 1,000 chess sets and related objects from over 100 countries.

This exhibition commemorates the 55th year that Dr. George and Vivian Dean have collected chess sets together. They purchased their first chess set in the Middle East and thereafter acquired a set in each country they visited. As they immersed themselves in chess history and joined a worldwide community of chess set connoisseurs, they expanded their collection more systematically. Now they travel to new countries for the sole purpose of acquiring new sets to make the collection more comprehensive. Their collection includes over 1,000 chess sets and related objects from over 100 countries.

The Deans have shared their collection with the public for purposes of study, research, and education. Selections from the collection have been shown at The Royal Academy of Arts and The Somerset House, London; the Musée d’Orsay and Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris; The Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, Washington; The Philadelphia Museum of Art; The 1990 Garry Kasparov vs. Anatoly Karpov World Chess Championship, Hotel Macklowe, New York City; and The Detroit Institute of Arts. For his book about their collection, Chess Masterpieces: One Thousand Years of Extraordinary Chess Sets (2010), Dr. Dean received the 2011 Cramer Award for excellence in Chess Journalism.

Introduction

In 2016, the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) celebrates its fifth year in Saint Louis. Animal, Vegetable, Mineral: Natural Splendors from the Chess Collection of Dr. George & Vivian Dean revisits the subject of one of the first exhibitions presented at the WCHOF. Chess Masterpieces: Highlights from the Dr. George & Vivian Dean Collection, on view from September 9, 2011 to February 12, 2012, offered our visitors a first look at a selection of precious chess sets from the Deans’ collection. The rare and beautiful chess sets provide a unique view of the past, whether through the stories of the individuals who owned them or the tales they tell through their iconography.

Chess set collectors have a special place in the history of the WCHOF. When the institution was located in Miami, Florida, from 2001 to 2009, collectors including Dr. George and Vivian Dean, Bernice and Floyd Sarisohn, and Frank Camaratta, among others donated a number of sets to build the institution’s collection and illustrate the diversity and history of chess sets from different eras and locations. Since the WCHOF moved to Saint Louis in 2011, we have hosted two meetings of Chess Collectors International (CCI), an organization that Dr. George Dean founded in 1984 for the study and promulgation of the art and history of chess artifacts. Additionally, Barbara and Bill Fordney have donated sets to the WCHOF’s collection, and many members of CCI including the Deans, Richard Benjamin, Jon Crumiller, Duncan Pohl, Bernice and Floyd Sarisohn, and Allan Savage have loaned artifacts for our shows.

After 24 exhibitions, we are pleased to again work with Dr. George and Vivian Dean and guest curator Larry List. Animal, Vegetable, Mineral exhibits some of the sets from the prior exhibition, including the Fabergé Kuropatkin Chess Set and Rock Crystal Chess Set, as well as others never previously shown at the WCHOF. They are presented within a framework that emphasizes the artistry with which the sets were created. This blend of art, history, and science is a perfect illustration of the WCHOF’s mission to present exhibits exploring the artistic and cultural significance of chess.

—Emily Allred, Assistant Curator, World Chess Hall of Fame

From the Curator

Dr. George and Vivian Dean have been fascinated with chess sets for over half a century. Their collection of more than 1,000 sets and diverse singular pieces stretches from the 8th century to the present, with examples from as many different cultures and eras as they have been able to find. Their criteria for selecting works have been: aesthetic beauty, quality and diversity of materials, and quality of craftsmanship. In assembling an exhibition from their collection, what rational guide can be used to select the works? What organizational template can be used to present the works in a way that most fully reveals them and celebrates their creation? With the Deans’ interests and criteria in mind, two prominent figures from the Age of Enlightenment in Europe and their respective masterworks suggest answers to these questions of selection and presentation.

Dr. Dean is a physician as was Carl Linnaeus, the noted Swedish scientist who in his book Systema Naturae (1735) proposed the first comprehensive system of organizing the entire natural world into animal, vegetable, and mineral kingdoms. Hence, it was decided that the works for this exhibition would be selected on the basis of being exceptional examples of these categories of subjects or materials.

The Deans’ three areas of interest—art, diverse natural materials, and quality craftsmanship—are reflected in the title of the famous 1751 publication Encyclopaedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts, edited by the French scholar Denis Diderot. Competing with Linnaeus’ aspiration to classify all the natural world, Diderot’s grand ambition was to present an overview of all human knowledge. His work was noteworthy as the first publication to view the contributions of the skilled trades, or “crafts,” (later termed engineering) as co-equal to those of the arts and natural sciences. Inspired by the tripartite template of Diderot’s Encyclopaedia, this is the first exhibition to present the Dean Collection chess sets as expressions of the arts, and to exhibit them with natural science specimens of the materials from which they were made along with examples of the types of craft tools and illustrations of the processes used to make them.

Subjects

In Europe during the Age of Enlightenment, an expanding prosperous, literate, and increasingly secular population took interest in everything from such bold, ultimately practical experiments as James Watts’ steam engine and the discovery of a European formula for hard paste porcelain to Diderot’s attempts to catalog the arts, sciences, and crafts to Linnaeus’ classifications of the natural world. Some members of this broad, scientifically-curious audience sought out decorative artworks, like chess sets, with natural specimens of many kinds as subjects. The Italian Butterflies and Insects Chess Set and Board (c 1790), with ivory or ebony pieces painstakingly modeled after a specific species of butterfly or moth, is a prime example. This interest in natural subjects has continued unabated ever since.

Study of the animal kingdom by naturalists and patrons, such as King Augustus the Strong of Poland, who had his own private zoos, provided a vast stock of specimens for artists creating chess piece subjects, both for play and display. King Augustus also financed the European discovery of porcelain and established the Meissen porcelain works in 1708. There he initiated the tradition, maintained to this day, that his artists model pieces directly from actual animals. The specificity gained from this life drawing mandate lends special vibrancy to such Meissen sets as the Sea Life Chess Set and Board (c 1925), in which each minutely detailed species of creature can be identified. Royal Doulton, established in London in 1815, followed Meissen’s lead on modeling animals from life but added such endearing details as enlarged eyes and facial expressions to sets such as their Porcelain Mice Chess Set (1885). However, imagined or idealized animals do also appear, such as the mythological sea creatures in the Italian Poseidon and his Retinue chess set (late 1700s). Human figures and even human fingers have provided lively subjects for artists included in the Dean Collection. 20th-century Surrealist master Salvador Dalí actually took plaster casts of his fingers and those of his wife, Gala, in 1964 to design his silver and gold Jeu d’échecs (c 1972), which was finally produced in 1971 or later.

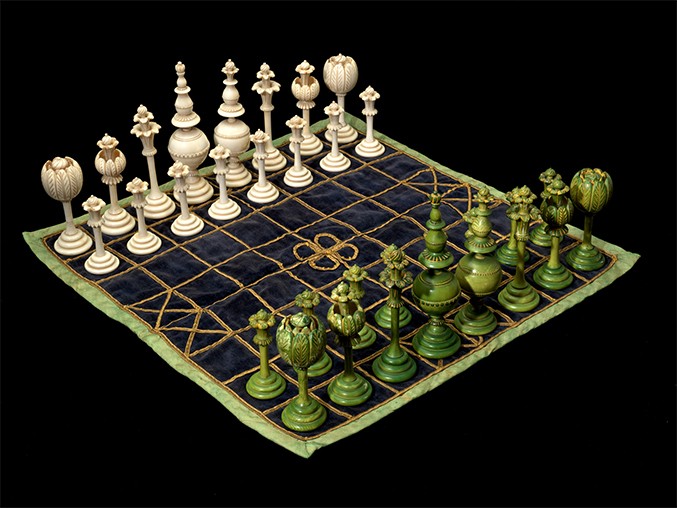

Plants, too, have provided inspiration as subject matter of great symbolism, history, and decorative beauty. Since they were not encouraged to portray human or animal forms, Muslim artists took special interest in botanical imagery, reflecting the Turkish sultans’ extensive study, collection, and breeding of plants. Hence, in the Turkish Tulip Style Chess Set (date unkown), different pieces depict the growth cycle of the flowers while the Mushroom Style Silver Chess Set and Board (1600s) portrays more idealized silver mushroom-forms as surfaces to be covered with profuse incised blooming flower decorations.

Materials

The finest chess sets have always been made of either the richest materials native to their owners’ region or of exotic, costly materials from afar which reflected the owner’s wealth. Artisans chose media either because they were easy and exible to work with or conversely, because they were technically demanding and would showcase the artists’ superior skills.

For centuries, the animal kingdom has provided craftsmen with valuable materials. Ivory tusks and teeth from walruses, narwhals, whales, and elephants long were among the most ideal materials for fine carving, as evidenced in the detailed menagerie of Indian animals in the Juggernaut Cart Set (late 18th or early 19th century), made from elephant ivory. In past eras before the species became endangered, thin veneers of turtle shell, commonly referred to as “tortoise,” were used to style lustrous, mottled silhouette chess pieces such as the Silhouette Tortoise Chess Set and Board (early 1900s) from Puerto Rico. The fine, even grain of coral, which is the calcified exoskeletons of sea animals, has made it ideal for detailed carvings which could be polished to a high luster, as seen in the Japanese Carved Coral Figurative Set (1800s).

Among the most exotic of materials formed in nature and used in chess sets are pearls, concretions of aragonite and calcium carbonite hosted by living animals, oysters. Over 100 pearls can be seen along with sparkling polished amethysts adorning the Silver Gilt Enamel Hungarian Chess Set and Board (1900s), a tour-de-force of silversmithing, relief casting, decorative engraving, and cloisonné enameling.

The vegetable kingdom has provided carvable soft woods, like the boxwood used to produce the Swiss Bears of Bern Chess Set (1800s), and hardwoods such as those used in the Danish Hawking Kings Chess Set (1800s) and the masterful Carved Wood Relief and Inlaid Board (1600s), which was produced in the woodworking center of Eger, Hungary. Fossilized pine resin forms the marvelous, gem-like carving medium amber that ranges in color from the lightest translucent yellow tints to the darkest wine reds. Empress Catherine the Great of Russia (1729-1796) was an avid chess player and lover of this material. She had an amber carving workshop in St. Petersburg and maintained her own royal amber mines in Kaliningrad, Russia. The Catherine the Great Chess Set and Board (late 1700s), once owned by the empress herself, is the centerpiece of the six French and Polish amber sets included in this exhibition, their styles ranging from the near abstract to portrait-specific figuration.

In Asia, since 618 C.E., the Asian lacquer tree (Toxicodendron vernci uum) has yielded the type of sap essential to the production of hard, water-resistant Japanese and Chinese lacquers, like those used on the 20th-century example of the traditional Pingyao Decorated Lacquerwork Folding Board. The rich red and black colors are determined by the varied amounts of iron oxide added to the clear urushi medium.

From the mineral kingdom come “soft stones,” like the easy-to-carve soapstone and jadeite used in the Inuit Chess Set and Board, (1966); the frothy, meringue-like meerschaum of the 20th-century Turkish Meerschaum Chess Set; and the translucent alabaster of the Portuguese Carved Alabaster Chess Set and Board (20th century). Durable hard stones such as fluorspar and the many varieties of marble have been widely used in chessboards, with the term “pietre dure” referring to the discipline of “painting in stone,” by creating complex images or decorations of individually cut, inlaid stone veneers. This technique can be seen in the French Inlaid Stone Chessboard (1600s) and the round Indian Inlaid Marble Chessboard (1965).

Minerals, often rare and featuring stunning colors, unique crystalline structures, and dramatic patterns, can serve as both material from which a chess set is made as well as being subject of the chess set itself. Designed to dazzle either by candlelight or by sunlight, the Rock Crystal Chess Set and Board (1525) is the only complete set of its style and type extant. Mounted in silver and gilt bases and topped with hand-wrought crowns, horses’ heads, and caps, the hand-cut, contoured, and polished natural crystal “bodies” of the pieces are faceted to reflect and refract light in all directions as are the alternating clear and smoky crystal squares of the board, each under-laid with reflective silver and gold foil.

Using a similar design strategy almost 400 years later for the Fabergé Kuropatkin Chess Set, Board, and Presentation Case (1905), Master Karl Gustav Hjalmar Armfeldt relied on an impeccable selection of rare minerals and the unparalleled technical finesse of his studio craftsmen.

The flawless tawny aventurine quartz and kalgon jasper of the opposing chess pieces are set off by a board made of Siberian jade and apricot serpentine trimmed with tawny aventurine. The perfectly cast and engraved silver bases, crowns, and board framing details all harmonize with the simple, elegantly proportioned symmetric forms to keep drawing the eye back to the inherent beauty of the minerals themselves.

The mixing and compounding of minerals expanded artists’ material possibilities much further, resulting in clays such as terracotta (iron, kaolin, and hydrous aluminum), with Meissen’s special Böttger ware formula popularized by such sets as the Animal Chess Set with Bowl first produced in the 1920s, and European hard-paste porcelain (kaolin and ground alabaster), represented in this exhibition by the aforementioned Royal Doulton Porcelain Mice Chess Set (1885), the Frogs Chess Set, and Sea Life Chess Set and Board (c 1925). Glass, a basic combination of soda, lime, and silica, with an admixture of uranium salts, makes up the Austro-Hungarian Biedermeier Chess Set (1820-1840). The addition of lead oxide to the basic glass recipe resulted in the Val Saint Lambert Set (1920s). In the 20th century, steel (primarily iron and carbon) was used to produce the Swedish SKF Company Ball-Bearing Chess Set (1900s).

It is important to remember that in the past eras, when these rare artworks were made, many of these natural materials were more plentiful and widely accessible than they are today. Their sources were not endangered then, as some are considered now. These works represent a record of the attitudes, cultures, and craftsmanship of those past ages and were collected to be exhibited in a spirit of respect and reverence for nature, art, and craft.

Photo © Austin Fuller

Crafts

While cultures across different eras and around the world developed distinct styles of chess sets, all artisans had to perform similar processes to create them. Though the artisans developed independently, instincts and necessity often led them to make similar tools. The same tools might also have been used to work with different media. Ivory carving tools might, in turn, also be used on soft stone, amber, or wood. Many of these tools may look crude or home-made because they often were. Quality materials were expensive or scarce and were used only in the artworks. Cutting edges and specific forming implements had to be the best quality available but otherwise tools were often made of simple scrap materials.

Just as animal, vegetable, and mineral materials offered different creative possibilities to designers, so too did the different craft processes: carving, forming, turning, and casting.

Chess sets as diverse as the Swiss Bears of Bern Chess Set, Danish Hawking Kings Chess Set, Indian Juggernaut Cart Set, French Battle of Jarnac Chess Set (1600s), Inuit Set, Japanese Carved Coral Figurative Chess Set (1800s), and Italian Pedestal Busts Chess Set (1700s) are all examples of carving in varied materials. With the help of blades, drills, chisels rasps, and les, craftspeople carve, raw material to create one nished form at a time.

Forming techniques enable artists to shape or decorate hollow three-dimensional forms from highly exible types of sheet metal such as brass, copper, lead, pewter, silver, or gold. The basic hollow mushroom forms of the pieces in the Syrian Mushroom Style Silver Chess Set (1600s) were developed by hammering pieces of sheet silver over other harder solid convex forms (raising) then decorating the surfaces with linear designs hammered down into the surface with specially shaped chisel-like punches (chasing). Over three hundred years later, the Embossed Copper Chessboard (20th century) was created using the same basic hammer and punch technique.

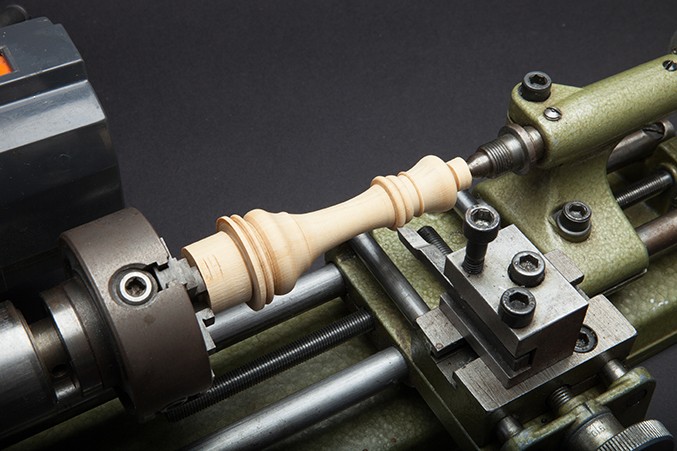

The Turkish Tulip Style Chess Set (date unknown), English Staunton Chess Set (1850s), and the Swedish SKF Ball-Bearing Chess Set (mid-20th century) are all examples of turning. By turning raw material held firmly and spun between two fixed endpoints in a machine called a lathe, artists can make round or cylindrically-based pieces, shaping the materials with sharp chisels as they spin. The complex Chinese Manchu Dynasty Style Chinese Puzzleball Set (1800s), with its hollow, loose, lace-thin, concentric spheres turned inside each other from one solid ivory ball, exemplifies the epitome of lathe-turning prowess.

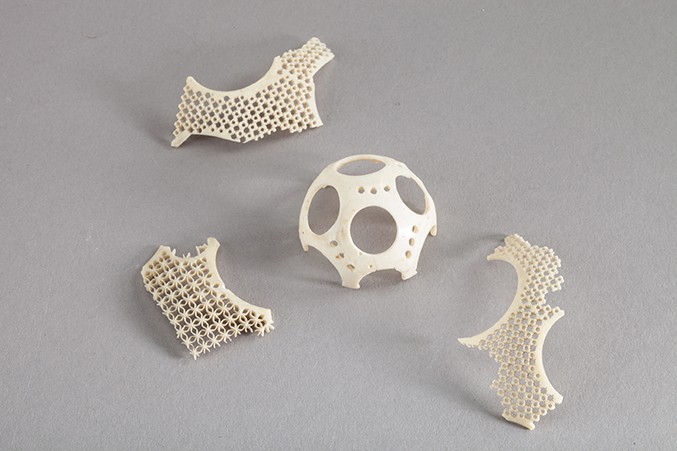

Casting is a process in which a hollow “mold” is made from an initial “master” model of a three-dimensional object. Once the “master” is removed, a fluid or molten material is poured into the mold, and cooled until solid. The “casting” is then removed from the mold and finished. Casting makes it possible to make multiple exact copies of the same form quickly and accurately. Artists chose to cast elements from silver in the Fabergé Kuropatkin Chess Set, Board, and Presentation Case and the Silver Gilt Enamel Chess Set and Board, the Biedermeier Chess Set from glass, the Royal Doulton Porcelain Mice Chess Set, among other sets in the show from clay, and the fine detail of the Zimmermann Cast Iron and Gilt Chess Set from common iron. The casting process, coupled with the formulation of durable hard paste porcelain in the 1700s and advances in iron metallurgy in the 1800s, made it possible to produce beautifully detailed porcelain and iron chess sets at prices that a much larger populace could afford, further popularizing the game of chess.

Artisans made most of the chess sets in this exhibition before the use of electrical power. Hence, the most sophisticated “tools” they had were their own skilled hands and the years of experience they had with their chosen materials. Pedals, treadles, steam, and electricity eventually provided power for some labor-saving devices, but surprisingly, many later generations of master artisans still preferred to use the same basic tools and techniques that were used in antiquity.

Chess, Art, Science, and Craft

By the end of his life in 1778, Carl Linnaeus had amassed one of the finest collections of natural history specimens in Scandinavia. He saw his life as a quest to capture nature’s diversity and harmony, believing that “the earth is then nothing else but a museum of the all-wise Creator’s masterpieces, divided into three chambers.” Scholar Lisbet Koerner described Linnaeus’ collection as his attempt to create a personal version of the Creator’s “world museum.” Assembled through careful study and sustained commitment, representing almost every culture, era, subject, material, and style, the Dean chess set collection might well be regarded as another personal “world museum.”

Like Diderot’s Age of Enlightment-era Encyclopédie, which employed 150 contributors, assembling this exhibition was a collaborative effort involving numerous experts in the arts, the natural sciences, and crafts, with our own “enlightened collectors,” Dr. George and Vivian Dean, at the center. Their collection, their “world museum,” makes it evident that chess sets and chess culture are not apart from life, but a part of life and the rich natural world that surrounds us.

—Larry List, Independent Curator

About the Curator

Larry List has researched and replicated estate-authorized versions of lost chess sets, artworks, and models by many artists. He organized both the exhibition and catalogue for The Imagery of Chess Revisited (The Noguchi Museum and The Menil Collection, 2006 – 2007). List co-curated and provided the major catalogue essay for 32 Pieces: The Art of Chess (Reykjavik Art Museum and DOX Centre of Contemporary Art, 2009) and curated Chess Masterpieces: Highlights from the Dr. George and Vivian Dean Collection (World Chess Hall of Fame, 2011 – 2012) and Cage & Kaino: Pieces and Performances (World Chess Hall of Fame, 2014). He contributed essays to the catalogues Duchamp, Man Ray, and Picabia (The Tate Modern, 2008), as well as to Communicating Rooks: The Work of Glenn Kaino (The Andy Warhol Museum, 2008). He is currently researching works by Surrealist Man Ray, Fluxus artist Takako Saito, and Minimalist Carl Andre.

Works Featured in the Exhibition

Wooden Chess Sets

John James Audubon (1785-1851)

Sparrow Hawk from The birds of America, from drawings made in the United States and their territories, 1840-1844

10 7⁄16 x 6 11⁄16 in.

Reproduction of a fine art print

Courtesy of the National Audubon Society

Eger, Hungary

Carved Wood Relief and Inlaid Board, 1600s

17 ¾ x 17 ¾ x 2 in.

Wood with carved bas-relief and colored marquetry

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Denmark

Hawking Kings Chess Set, 1800s

King Size: 5 in.

Painted hardwood

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Spain

Fruitwood Chessboard, 1800s

25 x 25 x ¾ in.

Fruitwood

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Replica European Fret Saw

Pine, maple and steel

Collection of Yuri Yanchyshyn, senior conservator, Period Furniture Conservation

Replica European Woodworking Tools: Thumb Plane, Maul, and Six Carving Chisels

Pine, maple and steel

Collection of Yuri Yanchyshyn, senior conservator, Period Furniture Conservation

Examples of Hand Cut Inlaid Wood Veneers

Assorted mahogany veneers, natural and stained, mounted on Plexiglas

Courtesy of Studio Associates, New York

Boxwood

France

Courtesy of the Japanese Repository

Russia

Karelian Chessboard, Date unknown

18 x 18 x 2 5⁄8 in.

Birch burl

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Bern, Switzerland

Bears of Bern Chess Set, 1800s

King Size: 4 in.

Pearwood

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Ernst Selhofer

Bern – Der Bärengraben—Berne La fosse aux ours (Bern—The Bear Pit), c. 1916

5 1⁄2 x 3 1⁄2 in.

Postcard

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

According to legend, in 1191 the bear became the symbol of Bern, Switzerland. In 1857, Bern added a sunken bear pit and bear plaza as centerpiece of the city. Thereafter, chess sets with a bear motif became a favorite subject for European wood carvers. Likewise, hunting with hawks and falcons was popular among the nobility of Europe and Asia and became another worthy subject for both chess sets and careful zoological study. The Danish Hawking Kings Chess Set, originally from the Margaard Castle on Funen Island, is distinctive in that the Queens are bearded males, who control the hawks.

The many species of wood in Europe’s forests encouraged artisans to develop the sophisticated carving and thin veneer inlay wood techniques seen in the Karelian Chessboard and Carved Wood Relief and Inlaid Board. The skilled craftsmen carved low relief scenes such as the Biblical seduction story of “David and Bathsheba” on the latter board. Small hand chisels like those on display in this exhibition were used both on the soft boxwood of the Bears of Bern Chess Set and the hardwoods of the Danish Hawking Kings Chess Set and Carved Wood Relief and Inlaid Board. The artisans cut out intricate designs with simple fretsaws from stacks of multi-colored hardwood veneers for the latter board. Examples here show the elaborate process necessary to transform a block of wood into a finished decoration.

Butterflies and Insects Chess Set and Board

Italy

Butterflies and Insects Chess Set and Board, c. 1790

Board: 12 ½ x 12 ½ x 3 in.

King Size: 4 in.

Ivory and ebony

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Elephant Ivory

Loxodonta africana

Courtesy of the Japanese Repository

Gravers and Carving Tools

Hardwood and steel

Courtesy of the Japanese Repository

Ebony

Diospyros crassiflora

Private Collection

Perhaps inspired by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus’ 1735 book Systema Naturae, which classified all of the natural world according to genus and species, Italian carvers crafted this chess set of butterflies vs. moths. Each piece represents a specific species of insect in either a larval or adult stage. Moths, active at night, are the black pieces, while the diurnal butterflies are white.

Ivory and ebony were chosen because of their durability and their ability to hold fine detail. With specimens or accurate drawings to guide them, the artists used an assortment of hand tools to carve the forms and incise pattern details onto wings and bodies. Most are identified by Latin inscriptions on their bases. Comparison of the chess pieces to the actual specimens on display in this exhibition, among them the White Queen, the Old World Swallowtail (Papillo machaon) and the White King, Chinese Scarce Swallowtail (Iphiclides podalirius), reveals how accurate the artisans were at depicting their subjects.

Tortoiseshell Chess Sets

France

Tortoise Chess Set and Board, c. 1900s

Board: 12 ½ x 12 ½ x 3 in.

King Size: 3 ½ in.

Tortoiseshell

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Replica Carving Point, Replica Separating Blade

Wood and steel

Private Collection

Natural Hawksbill Sea Turtle Shell

Eretmochelys imbricata

Collection of The Field Museum of Natural History

Polished Hawksbill Sea Turtle Shell

Eretmochelys imbricata

Collection of The Field Museum of Natural History

Worked Tortoise Shell Sample

Eretmochelys imbricata

Courtesy of the Japanese Repository

Puerto Rico

Silhouette Tortoise Chess Set and Board, early 1900s

Board: 12 x 12 x ¾ in.

King Size: 2 in.

Tortoiseshell

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Due to cost and limited thickness of the shells, most tortoise works, like this chess set from Puerto Rico, are made of thin veneers which create silhouettes. Some ingenious craftsmen, like those who made the French set (above), stacked many layers into larger solid pieces from which forms could be carved or lathe-turned. Steaming with salt water made bending very thin veneers over rounded forms like the sides of the chessboard possible.

Turtle shell, generically referred to as “tortoise,” was highly prized throughout Europe, Asia, and the Americas for its lustrous translucence and wide range of mottled color patterns. In this exhibition are examples of both raw and polished Hawksbill Sea Turtle shells. Both of these chess sets were made from similar shells but over half a century before Hawksbill Sea Turtles were declared endangered species in 1970.

Inuit and Indian Animal Chess Sets

Inuit Chess Set, c. 1966

Board: 16 x 16 x 3⁄4 in.

King size: 2 3⁄8 in.

Soapstone and jadeite

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Soapstone

Locality unknown

Private Collection

Rasps and Files, Hatchet, Polishing Leather, and Pocket Knife

Steel, hardwood, raccoon leather, fur, and antler

Private Collection

Awl, mid-20th-Century

Antler and iron

Collection: Dennos Museum Center, Traverse City, MI

Gift of Eskimo Art, Inc., Eugene B. Power, Founder

Delhi, India

Juggernaut Cart Set, late 18th or early 19th Century

Tallest piece size: 5 3⁄4 in.

Ivory

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Elephant Ivory

Loxodonta africana

Courtesy of the Japanese Repository

Replica Indian Style Carving Tools

Pine, steel, and twine

Private Collection

Featuring polar bears, seals, elephants, horses, and lions, the two animal-inspired sets in this case exhibit two different styles of carving. These sets also offer two different arrays of animals. Inuit artists sought to create the essence of their subjects by simplifying and abstracting forms while the Indian carvers sought completeness through the rendering of countless minute details.

In addition to soft soapstone and jadeite that 20th-century Inuits carved with hatchets and files now acquired at hardware stores they also sometimes carved harder walrus or narwhal ivory, similar to the elephant ivory favored by Indian carvers. Though geographically and culturally far apart, for many generations the basic tools carvers from these two societies made themselves to sculpt their animal subjects were closely related.

Aquatic Life Chess Sets

Meissen, Germany

Frogs Chess Set, 1900s

King Size: 3 1⁄4 in.

Glazed Meissen porcelain

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Northern Leopard Frog

Rana pipiens

Hand-painted plaster cast

Collection of the Field Museum of Natural History, cast by Rachel Grill

Meissen, Germany

Max Esser

Sea Life Chess Set and Board, c. 1925

Board: 18 1⁄2 x 18 1⁄2 x 2 in.

King Size: 3 3⁄4 in.

Glazed Meissen porcelain

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Italy

Poseidon and his Retinue, late 1700s

King Size: 3 in.

Italian ivory

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Chess sets depicting aquatic animals range from the anatomically accurate to the mythologically fantastic. While the finely-carved Poseidon and his Retinue Set showcases an artist’s imagination in depicting the mythical Greek god of the seas, a frog cast from a natural specimen and drawings of sea life attest to the attention to the anatomical detail of the classic Meissen Frogs Chess Set, modeled by Alexander Struck, another Meissen master sculptor, from the Northern Leopard Frog (Rana pipiens). The Meissen Sea Life Chess Set depicts Kings and Queens as anemones, Bishops as lobsters, Knights as seahorses, Rooks as octopi, and pawns as starfish.

Porcelain Animal Chess Sets

England

Royal Doulton Porcelain Mice Chess Set, 1885

King Size: 3 1⁄4 in.

Royal Doulton porcelain

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

House Mouse

Mus musculus

Saint Louis Science Center Collections

Slip-casting Mold, Wax Master, and Slip-casts of Knight

Plaster of Paris, paraffin, unfired porcelain clay, bisque-fired porcelain clay, and glazed porcelain

Slip-casting materials collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Courtesy of Michiko Shamada

Clay Sculpting Tools

Wood

Courtesy of Michiko Shimada

Meissen, Germany

Max Esser

Animal Chess Set with Bowl, 1920s

Bowl: 9 3⁄4 x 9 3⁄4 x 5 1⁄2 in.

King size: 3 3⁄8 in.

Terracotta Böttger ware

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

White hard paste porcelain had been produced in China since the Han Dynasty (206-220 C.E.). However, it was not until 1708 that the European alchemists Johann Böttger and Ehrenfried Walter von Tschirnhaus, working for fanatical porcelain collector and Polish King Augustus II, discovered a European porcelain formula of finely ground alabaster and kaolinite (a type of aluminum silicate also referred to as kaolin or “china clay”). Augustus II set up the Meissen workshop to produce ceramics for himself, including hundreds of clay animals modeled from the live beasts he kept in his numerous private zoos.

Ceramics factories sprang up across Europe, including Royal Doulton, which by 1855 had produced this popular Porcelain Mice Chess Set, modeled after real mice such as the specimen house mouse (Mus musculus). The tradition of finely sculpted ceramic animals continued into the 20th century with works like Animal Chess Set with Bowl by noted Meissen artist Max Esser. This set is unique in that Esser modeled the animals exactly, but then he carefully elongated them vertically to add Art Deco elegance. Originally offered on a round ceramic plate-like board, then in the pictured covered, tureen-like bowl, the Esser set reminds viewers that production of lavish table services was among Meissen’s major responsibilities.

Lathe-Turned Chess Sets

England

Staunton Chess Set with Jaques Carton-Pierre Papier-mâché Box, 1849

Box: 7 x 6 x 4 in.

King Size: 4 1⁄2 in.

Chess Set: Natural and red-stained African ivory

Box: Carton-Pierre and velvet

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Lathe Turning Chisels

Wood and steel

Private Collection

Unimat Lathe

Steel, rubber, and electrical wiring

Courtesy of DCM Fabrication

Staunton Style Half-turned Chess Piece

Boxwood

Courtesy of the Japanese Repository

Sweden

SKF Company

SKF Ball-Bearing Set, 1900s

King Size: 2 3⁄4 x 3⁄4 in.

Gilded and silver-plated steel

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Ecuador

Silver Chessboard, 1900s

10 x 10 x 1 in.

Ecuadorian silver

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Ball bearing

Steel

Courtesy of DCM Fabrication

Roller bearing

Steel

Courtesy of DCM Fabrication

Designed by Nathaniel Cooke, endorsed by English chess champion Howard Staunton, and produced in ivory and wood versions by John Jaques of London, this Staunton Chess Set is the most ubiquitous chess set style in the world. Though its forms were inspired by the antique marble sculptures taken from the Greek Parthenon by the British Earl of Elgin, John Jaques of London employed the most up-to-date industrial revolution age lathes and tools to produce these sets.

Lathe-turned and inspired by 20th-century abstraction, industrial culture, and materials, the SKF Ball-Bearing Set was made from the type of actual ball and roller bearings that were essential to any machinery that had rolling or spinning parts. As in the 19th-century Zimmerman gilt cast iron pieces also on view in this gallery, the gold and silver plating on these SKF industrial steel pieces imbues them with a classic sense of beauty.

Though hand-crafted from a traditional precious metal and trimmed with hammer-flattened woven wire, the Ecuadorian Silver Chessboard incorporates a mechanically-embossed pattern spread across the board’s surface. It provides a graceful compliment to the industrial steel ball bearing chess pieces.

Tulip Style Chess Sets

Turkey

Abstract Tulip Style King, Queen, Bishop, and Two Rooks, 1700s

King Size: 10 5⁄8 in.

Ivory with intarsia (inlaid color designs)

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Turkey

Tulip Style Chess Set, date unknown

King Size: 6 in.

Natural and green stained ivory

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Turkey

Ashtapada Chessboard, 1700-1900

17 1⁄2 x 17 1⁄2 x 1⁄4 in.

Velvet and gold embroidery

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Replica Model Bow Lathe and Turning Chisels

Wood and metal

Private Collection

Turkish Tulip Style Half-turned Chess Piece

Boxwood

Courtesy of the Japanese Repository

Turning Chisels

Wood and metal

Private Collection

Metalworking Files

Steel

Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis

The genus name “Tulipa” is based on “tulbend,” the Turkish word for turban. Turkish Sultan Suleiman I (1494-1566) began a craze for tulip collecting long before the Dutch tulip-mania in the Netherlands of the 1630s. Successive Turkish rulers continued to cultivate tulips eventually leading to the reign of Ahmed III (1703-30), which was known as the “Age of the Tulips” and the rst royal tulip festivals, which are still held in Istanbul every April and May.

Discouraged from representing human or animal forms by the Islamic holy book, the Koran, Muslim artists drew inspiration from the Turkish love of tulips to create this popular style of chess pieces depicting the sprouting and blooming phases of the owers’ growth.

Earlier generations of craftsmen made deft use of the traditional bow lathe, similar to the one on display, to turn the forms from wood or ivory. They often turned the different-sized elements from individual pieces of material to conserve precious material. They would then hand carve details, t the components together, and decorate them with elaborate red, blue, and green abstract color inlays, called intarsia, or representational ower motif color inlays called marquetry.

Mushroom-Style Chess Set and Embossed Board

Embossed Copper Chessboard, 20th Century

17 3⁄8 x 3⁄4 in.

Copper with walnut frame

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Syria

Mushroom Style Silver Chess Set and Board, 1600s

Board: 15 1⁄2 x 15 1⁄2 x 3⁄4 in.

King Size: 2 1⁄2 in.

Silver and gilt and engraved sheet silver over wooden base

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Sculpting Hammer

Wood and iron

Private Collection

Maul

Wood

Private Collection

Engraving Burins

Wood, brass, and steel

Private Collection

Embossing Stamps

Metal

Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis

Sample embossed copper sheet

Copper

Private Collection

The Islamic holy book, the Koran, discouraged depiction of humans or animals so many Islamic design motifs were inspired by plants. The forms of the Mushroom Style Silver Chess Set pieces are idealized stems and caps of mushrooms whose surfaces were then decorated with blooming flower motifs, with the pieces of one side then gilt. In like manner, every board square has a concentric flower motif except for the central and border squares marked with “Xs” to enable the playing of Ashtapada, the board game that pre-dates chess.

This set and board are superb examples of three related decorative embossed metal techniques: “chasing,” which is a process of using hammer and punches to drive designs down into the top surface of sheet metal; “repoussé,” which also involves hammers and punches and pushes designs up into a surface from beneath or behind it; and “engraving,” the process in which lines of metal are carved away using pointed tools called burins.

Along with gold and silver, copper was most often used for this type of metalwork. Though created four hundred years later than the Syrian works, the Embossed Copper Chessboard from the 20th century was made with the same basic techniques and tools.

Amber Chess Sets

Red Amber

Locality unknown

Saint Louis Science Center Collections

Poland

Amber and Silver Set and Board, 1860

Board: 12 1⁄2 x 12 1⁄2 x 3 in.

King Size: 3 1⁄4 in.

Amber, silver, velvet, and wood

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

This chess set combines two valuable natural resources from Poland: amber and silver. Delicately carved amber full-figure pieces sit atop finely detailed silver bases, gilt on one side, with a signature or makers’ mark on the base of the King. With the exception of the traditional tower-style Rooks and the Queens, all other pieces, including the Bishops, wear 19th-century military uniforms. These chess pieces sit atop a luminous orange amber board inset into a velvet-clad wooden case that unlocks to provide storage for the entire set.

Amber

Locality unknown

Collection of Washington University in St. Louis, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences

Poland

Opaque and Translucent Amber Set and Board, 1800s

Board: 10 3⁄8 x 10 3⁄8 x3⁄4 in.

Tallest Piece Size: 2 in.

Amber and wood

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

This set made of small, simplified, and indestructible forms is well-suited for travel. They are simple lathe-turned and carved columnar pieces, all created from opaque amber, one side golden yellow, the other a vivid red-orange. Bordered by an oak frame, each of the 64 squares of the board is comprised of an individual multicolored patchwork of 10 to 12 irregular oblong amber tiles.

Replica Amber Carving Tools

Pine and steel

Collection of Yuri Yanchyshyn, senior conservator, Period Furniture Conservation

Russia

Catherine the Great Chess Set, Late 1700s

Board: 15 x 15 x 2 in.

King Size: 3 in.

Amber and ebony

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Empress Catherine the Great of Russia (1729-1796) was an avid chess player. She had an amber carving workshop of German craftsmen in St. Petersburg and her own royal amber mines in Kaliningrad, Russia. Kaliningrad is still today the world’s largest single source of amber. Her love of amber from the lightest yellow tints to the darkest wine reds may have created a resurgence of its popularity across Eurasia in the 1800s, especially raising the level of the carving craft in Poland and the rest of the Baltic region.

Displayed on a board of alternating amber and ebony inlays with ebony beading and borders, these variegated amber pedestal bust pieces are bookended by Indian-style elephant-head Rooks. Catherine is paired with her lover and minister, Prince Grigori Potemkin, and surrounded by Russian style soldiers while her son, Prince Paul I, and his wife oppose her and are accompanied by soldiers in more Germanic garb. Related copies of this set are in the collections of the Hermitage and the Royal Danish Collection at Rosenberg Castle, Copenhagen.

Poland

Amber Chess Set and Board, 1800s

Board: 7 1⁄2 x 7 1⁄2 x 1 1⁄2 in.

Tallest Piece Size: 1 1⁄2 in.

Amber

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

In this miniature set, boldly carved portrait busts of nobles are protected by lathe-turned stacked-disk abstract pawns. Like the late 1700s Greeks vs. Egyptians Set and Board in this case, this board is surrounded by a stockade of upright half-round sections of translucent reddish-brown amber. Corner segments have low-relief carvings of Queens and Knights in profile, while each side is accented with two segments carved with bold decorative geometric patterns. A carved portrait head mounted sideways acts as a drawer pull to open a storage space for the pieces beneath the golden and honey-yellow amber board surface.

France

Greeks vs. Egyptians Set and Board, Late 1700s

Board: 9 1⁄2 x 9 1⁄2 x 1 in.

Tallest Piece Size: 2 3⁄4 in.

Amber

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

A stockade of upright half-round sections of solid opaque amber surrounds the board of this exquisite diminutive chess set. The board’s surface has a crisp silver grid precisely fit with uniformly alternating opaque orange and translucent red squares of amber. Each square is underlaid with a silver relief panel sporting European-style fleur de lis decorations based on iris flowers.

Finely carved and proportioned full figures in brilliant opaque orange amber portray a helmeted Alexander the Great leading his Greeks with a scepter. His Queen wears a loose, classical full-length peplos garment. Greek soldiers as pawns are armed with swords, round shields, and helmets. Greek Ionic columns represent the Rooks.

The Egyptian forces are sculpted in deep translucent wine red amber with the long-robed Persian ruler of Egypt, Darius III, holding a staff overseeing his soldier armed with maces and bounded by Rooks in the form of decorated obelisks.

Amber with Preserved Insects

Dominican Republic

Collection of the Field Museum of Natural History

Poland

Max Simon

Amber Set and Board, 1850

Board: 15 x 15 x 2 5⁄8 in.

King Size: 3 1⁄4 in.

Amber

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Commissioned by a patron living in Posen, one of the oldest cities in Poland, during an era of contention over Prussian control, the pieces in this set may portray native Poles vs. Prussians. Germanic-style stone tower Rooks contrast with ones of the Eastern Orthodox onion-domed style more common to Poland. Since Posen was a city of commerce on a major East-West trading route, the pawns each portray a different trade.

Because amber was the product of fossilization, pieces free of bubbles and flaws are relatively small and variations of color are frequent. This set and board are notable for the almost

perfectly consistent color throughout. Carved decorative panels of helmeted knights and fruit motifs in contrasting darker amber hide seams between the large flat planes that make up the splayed sides of the dark-edged board.

Amber has been used for decorative objects since Neolithic times. As a translucent fossil material, amber has preserved insects or plants from as long ago as 230 million years. As recently as the 20th century, amber has also been used as a folk medicine, an element in perfumes and a flavoring of aquavit liquor.

Silver Gilt Enamel Chess Set and Board

Hungary

Silver Gilt Enamel Chess Set and Board, 1900s

Board: 22 x 22 x 2 3⁄4 in.

King Size: 3 1⁄2 in.

Silver, gilded silver, enamel, pearls, amethyst, and wood

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Amethyst

Locality unknown

Saint Louis Science Center Collections

Gold

Kalgoorlie, Australia

Collection of Washington University in St. Louis, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences

Silver Nuggets

Creede, Colorado, USA

Collection of the Field Museum of Natural History

Seashell with Pearls

Locality unknown

Collection of Washington University in St. Louis, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences

This chess set and board is a tour-de-force of silversmithing, relief casting, decorative engraving, and cloisonné enameling. Here, Kings and Queens wear ruby red enameled capes. One set of courtiers is cloaked in royal lapis lazuli blue, while the others sport brilliant cerulean garments with white accents.

In cloisonné, the contour edges of each metal surface to be colored are outlined with wire, which holds in place powdered enamel (in paste form) while the piece is heated in a kiln, or oven. The heat fuses the enamel paste to the metal surface as a glassy, jewel-like layer.

Pieces and board alike are edged with delicate filigree details and lavishly encrusted with over one hundred natural pearls and amethyst cabochons, raw gemstones polished to smoothly rounded forms. Splayed, relief carved, and cast gilt side surfaces are adorned with silver panels decoratively engraved with scenes of combat. These are coated with rich translucent turquoise and framed in pearlescent white enamel.

Carved Coral Figurative Chess Set

Japan

Carved Coral Figurative Chess Set, 1800s

King Size: 3 1⁄4 in.

White and orange coral

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

China

Illustrated Lacquer Work Chessboard, 1900s

22 1⁄2 x 25 x 1 1⁄4 in.

Lacquered wood

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

White Coral

West Indies

Saint Louis Science Center Collections

Finished Red Coral

Locality unknown

Collection of Washington University in St. Louis, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences

Replica Coral Carving Tools

Bamboo and steel

Collection of Yuri Yanchyshyn, senior conservator, Period Furniture Conservation

These carved coral figures suggest a festival procession with the King carrying an incense vessel; the Queen bearing a chrysanthemum, the symbol of rejuvenation; Bishop or priests holding Buddhist prayer beads; Knights riding on horseback; and Rooks styled as portable shrines. The pawns serve as chanters and musicians carrying short (biwa) or long-necked lutes (shamisen). Coral is a crystalline form of limestone created from the calcified exoskeletons of sea animals. Its hard, fine, even grain makes coral ideal for highly detailed carvings, which can be polished to a high luster.

This chessboard is an example of the elegant flower and landscape style lacquer work produced in the city of Pingyao, China. Pingyao wares have been produced since the Tang Dynasty (618-907 C.E.), and are much sought after, having been exported to Southeast Asia, Russia, and England from the time of the Manchu Dynasty (1644-1912 C.E.). The word urushiol derives from the Japanese word for the lacquer tree urushi (Toxicodendron verncifluum). Japanese and Chinese lacquers, made from urushiol-rich tree sap, were among the earliest man-made coatings resistant to water, acids, and scratching. Varying the amount of iron oxide added to the clear sap resulted in either red or black lacquer.Here, the chess squares with black craquelure pattern are bordered by sinuous branches of mottled red needle pine clusters. These frame junks, traditional Chinese sailboats, floating in a bottomless black ocean, all hand-buffed to a lustrous finish.

Chess Sets with Cast Metal Elements

Austria

Gilt Silver, Lapis Lazuli, and Malachite Chessboard, 1815

12 x 12 x 1 1⁄2 in.

Gilt, silver, lapis lazuli, and malachite

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Hanau, Germany

E.G. Zimmermann Company

Zimmermann Cast Iron and Gilt Chess Set, 1850s

Tallest Piece Size: 3 7⁄8 in.

Cast iron and gilding

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Malachite

Locality Unknown

Courtesy of the Japanese Repository

Lapis Lazuli

Afghanistan

Courtesy of the Japanese Repository

Italy

Pedestal Bust Chess Set and Board, 1700s

Board: 22 1⁄2 x 14 1⁄2 x 2 in.

King Size: 3 1⁄2 in.

Lapis lazuli, alabaster, coral, mahogany, marble, and fluorspar

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

The alabaster, coral, and lapis lazuli from which this 18th-century Italian Pedestal Bust Chess Set are made are soft enough to easily be carved yet fine enough to hold minute details. The harder marble and fluorspar inset in the mahogany Inlaid Stone and Wood Board make a durable playing surface that suggests a miniature palace floor.

White Marble

Locality unknown

Saint Louis Science Center Collections

Pink Marble

Tate, Georgia, USA

Saint Louis Science Center Collections

Alabaster

Locality unknown

Courtesy of the Japanese Repository

Fluorite

Rosiclare, Illinois, USA

Collection of Washington University in St. Louis, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences

Rhineland, Germany

Rock Crystal Chess Set and Board, 1525

Board:10 5⁄8 x10 5⁄8 x2 1⁄2in.

King Size: 2 3⁄4 in.

Carved rock crystal, smoky topaz, silver, and gilding

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

The rarity of flawless crystal (quartz) large enough to carve into chess pieces made it highly sought after by the nobility of European courts. This 16th-century Rock Crystal Chess Set and Board is the only complete set of its kind and era. The crystal “bodies” are mounted in silver and gilt bases and topped with hand-wrought crowns, horses’ heads, and caps of the same materials. The board is made from alternating clear and smoky crystal squares underlaid with silver and gold foil. The base has gilt silver moldings separated by a band of elaborately chased silver decorations. Each corner is supported by a gilt tortoise, a symbol of slow but determined warfare.

Quartz

Locality unknown

Saint Louis Science Center Collections

Smoky Quartz

Hot Springs, Arkansas, USA

Saint Louis Science Center Collections

European nobility highly prized chess sets made of gold, silver, semi-precious gems, and minerals at the time of this set’s creation. Advances in metallurgy and casting techniques in 19th-century Europe made finely detailed casting in common iron possible. The Zimmerman Cast Iron and Gilt Chess Set, which commemorates the victory of Germanic tribes over their Roman oppressors in 9 C.E., was the first of five fine designs sculpted by artist J.F. Malchow and cast by E.G. Zimmermann of Hanau, Germany. Silver plating and gilding transformed pieces cast of humble iron into noble artworks worthy of being displayed on an opulent Viennese Gilt Silver, Lapis, and Malachite Chessboard.

The Viennese Gilt Silver, Lapis, and Malachite Chessboard uses the intense natural colors and patterns of rich blue lapis lazuli, most likely from Italy or Afghanistan, and brilliant banded green malachite, most likely from the Ural Mountains of Russia, to create the decorative design of the board. These two types of stone were popular among jewelers and furniture designers as well as being prized by artists as finely ground permanent pigments for use in paintings.

Fabergé Kuropatkin Chess Set, Board, and Case

Russia

Fabergé Kuropatkin Chess Set, Board, and Case, 1905

Case: 3 1⁄8 x 25 3⁄4 x 19 1⁄4 in.

Board: 25 x 25 x 2 in.

King Size: 3 1⁄8 in.

Jade, jasper, serpentine, aventurine quartz, and silver

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Serpentine

Cardiff, Maryland, USA

Saint Louis Science Center Collections

Jadeite

Locality unknown

Collection of Washington University in St. Louis, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences

Jade

Petaluma, Sonoma County, California, USA

Collection of the Field Museum of Natural History

Pink Quartzite

Locality unknown

Saint Louis Science Center Collections

One of only two chess sets ever made by Fabergé, the Russian royal family commissioned this ensemble for General Alexi Nikolayevich Kuropatkin to commemorate his faithful service. The silver base of the board is decorated with flawless relief-sculpted acanthus and laurel leaf patterns and engraved in tribute to the general with the names of twelve or more royals, officers, and other major state figures. The board itself is made from squares of greenish Siberian jade and apricot serpentine framed by aventurine quartz. Studio master Karl Gustaf Hjalmar Armfeldt produced the set.

Similar in design to the Rock Crystal Chess Set and Board, also on view in this exhibition, the pieces for this set have precision turned and polished “bodies” made of tawny aventurine quartz and blue-grey kalgon jasper mounted in silver bases. Impeccably sculpted and cast crowns, horses’ heads, and caps created from the same silver top the pieces.

Manchu Dynasty Style Chinese Puzzleball Set

China

Manchu Dynasty Style Chinese Puzzleball Set, 1800s

King Size: 8 1⁄2 in.

Natural and red-stained ivory

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Puzzle Ball Fragments

Ivory

Courtesy of the Japanese Repository

Puzzle Ball Turning Tools

Wood and metal

Courtesy of Craft Supplies USA

Replica Chinese Style Ivory Carving Tools

Bamboo and steel

Collection of Yuri Yanchyshyn, senior conservator, Period Furniture Conservation

19th-century artisans in Canton, China, perfected the technique of creating ivory ball-in-ball, or puzzleball, bases for the fine chess sets it produced for export by the British East India Trading Company. Each base has hollow, loose, lace-thin, concentric spheres, which were lathe-turned and carved inside each other from one solid ivory ball. Success in producing these puzzleballs was dependent upon taking the time to craft a special set of metal lathe-turning chisels, measuring and cutting accurately, and maintaining patience and focus throughout a long tedious process. Rich floral and figural sculpted designs cover the outermost surfaces of the balls, echoing the complex hand-carved detailing on the Manchu Dynasty clothing of the chess figures.

Chess Sets Made From Glass

Belgium

Val Saint Lambert Set, 1920s

King Size: 7 1⁄4 in.

Clear and green crystal

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Master artisans created the Val Saint Lambert Set one unique piece at a time by shaping bits of molten glass using a blow pipe, a pontil (handling rod), and other simple hand tools developed over the centuries such as jacks, tweezers, scissors, and diamond shears. This process was so demanding and complex that only three chess sets of this design were ever completed. Founded in the abandoned Val Saint Lambert Abbey at Seraing, Belgium, in 1826, the Val Saint Lambert luxury glass works distinguished itself in the 20th century as an outstanding producer of Art Deco style works like this chess set.

Tweezers, Diamond Shears, Blow Mold, Shears, Paddle, and Jacks

Metal

Collection of the Wheaton Arts & Cultural Center

Austro-Hungary

Biedermeier Chess Set, 1820-1840

King Size: 2 3⁄4 in.

Uranium glass and gold oxide

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

India

Inlaid Marble Chessboard, 1965

15 in. diameter x 3⁄4 in. height

Marble with inlays

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

In contrast, each folk-style figure in the Biedermeier Chess Set was formed in a reusable mold. The glass contains bright yellow uranium salts, a formula popularized by Bohemian glassmaker Josef Riedel. After being molded and cooled, a face was hand- painted on each piece. Though not containing enough uranium to be harmful to players, the pieces will glow bright green under ultraviolet light.

France

Battle of Jarnac Chess Set, 1600s

King Size: 3 in.

Amber and ivory

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

France

Inlaid Stone Chessboard, 1600s

21 x 21 x 1 1⁄2 in.

Various stones

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

The Battle of Jarnac Chess Set depicts the victory of the Catholics over the Huguenots in a March 13, 1569, conflict during the French Wars of Religion. The pieces represent specific historical figures. It is an interesting study of the origins and continuity of French amber carving style in relation to the Greeks vs. Egyptians Chess Set and Board, created by other French craftsmen over a century later.

Chess Sets Made From Hard and Soft Stones

Turkey

Meerschaum Chess Set and Board of Carrara and Siena Marble, 1900s

Board: 15 1⁄2 x 3⁄4 in.

King Size: 4 in.

Meerschaum and Carrara and Siena Marble

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Black and Gold Marble

France

Saint Louis Science Center Collections

Stone Carving Tools and Carving Hammer

Steel and wood

Private Collection

Meerschaum

Utah, USA

Courtesy of the Japanese Repository

Allen Hempel

Carved Alabaster Chess Set and Alabaster Board, 1900s

Board: 22 1⁄8 x 22 1⁄8 x 2 1⁄4 in.

Tallest Piece Size: 9 1⁄2 in.

Alabaster

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean

Like soapstone, meerschaum and alabaster are described as types of “soft stone,” which readily lend themselves to fine carving, as displayed in the Meerschaum Chess Set and Carved Alabaster Chess Set and Board. Always white, light grey, or cream colored, meerschaum is mined most abundantly in Turkey. Since the 1700s, artisans have fashioned it into pipes and decorative objects. Alabaster, which has been used in sculpture since the 4th millennium BCE, can vary in color from white to rich reddish brown, with only three small mines in the world yielding a black variant. The thinner alabaster is cut, the more translucent it becomes, giving forms carved from it a special life or “aura.”

In contrast, the figured marble of the Italian chessboard is regarded as “hard stone,” with many patterned types identified by the specific locale from which they are quarried. The white stone from Carrara has been among the most highly prized for sculpture ever since the Renaissance while the black Portoro (“golden door”) marble found in nearby La Spezia had been used decoratively since Etruscan times. Examples of each type of marble are on view in this exhibition.

Dean Collection Images © Dean Collection 2010. Richard Beenen Photography.

Specimen and tool photography by Michael DeFilippo.

Press

3/11/17: Designing Chessmen (video)

1/20/17: World Chess Hall of Fame Blog — The Rock Crystal Chess Set: A Study In Timely Warfare

10/20/16: ArtDaily.org — Exhibition at World Chess Hall of Fame Showcases World-Class Chess Collection

9/28/16: St. Louis Public Radio — On Chess: New exhibit at the World Chess Hall of Fame draws inspiration from ‘Systema Naturae’

9/20/16: Webster-Kirkwood Times — World Chess Hall of Fame Celebrates 5th Anniversary

9/20/16: Chess Base — Three new exhibitions at the World Chess Hall of Fame

9/18/16: Chessdom — World Chess Hall of Fame celebrates five years in Saint Louis

9/16/16: Press Release — World Chess Hall of Fame Celebrates Five Years in Saint Louis, Debuts Three New Exhibitions Spanning Nearly Five Centuries of Chess & Art (download)