You do not need to be a chess player to understand the impact that Bobby Fischer had on the game of chess.

On View: July 24, 2014 – June 7, 2015

Born Robert James Fischer on March 9, 1943, he received a $1.00 chess set from his sister Joan when he was six, and his love of the game quickly blossomed. Already showing a proclivity for puzzles and advanced analytical thinking, a young Bobby began what his mother Regina referred to as an obsession for the game. Little did she know that this passion would eventually lead to her son becoming the World Chess Champion, ending 24 years of Soviet domination of the game in 1972 and changing the way the entire world would view chess.

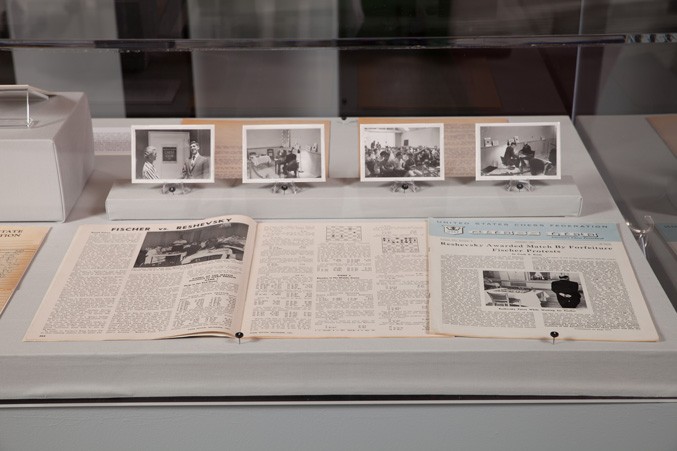

A Memorable Life: A Glimpse into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer presents a few key moments in the storied life of a man who was both a source of intense admiration and controversy. Beginning with his rise to fame as a young boy, this exhibition includes material related to his early training with teachers Carmine Nigro and Jack Collins, many of the major tournaments in which he participated, as well as his historic World Chess Championship victory, and his later retirement from tournament play. Through artifacts generously loaned from the Fischer Library of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield, we are given unprecedented access to Fischer’s preparatory material for the 1972 world championship run, as well as the initial versions of his classic text My 60 Memorable Games. Never before exhibited, these materials supplement highlights from the collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, donated by the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky, which include photographs, correspondence, and other artifacts related to his 1961 match against Samuel Reshevsky. These remarkable artifacts illuminate Fischer’s brilliance, showing how he revolutionized American chess.

—Shannon Bailey and Emily Allred, 2014

Inside an Enigma: The Fischer Library of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

More literature is devoted to chess than all other games combined, but today it is not uncommon to find world class players who seldom open a book. Long-running publications like Chess Informant continue to be published, but young stars of 2014 do almost all their study with a computer, be it by accessing databases with millions of games and analyzing them with powerful engines, or by playing online against opponents around the globe. This certainly was not the case when Bobby Fischer began his brilliant career. Bobby learned to play in March of 1949 and soon was reading his first chess book, quite possibly Siegbert Tarrasch’s The Game of Chess. This was the start of a life-long love of chess literature that was to serve him well.

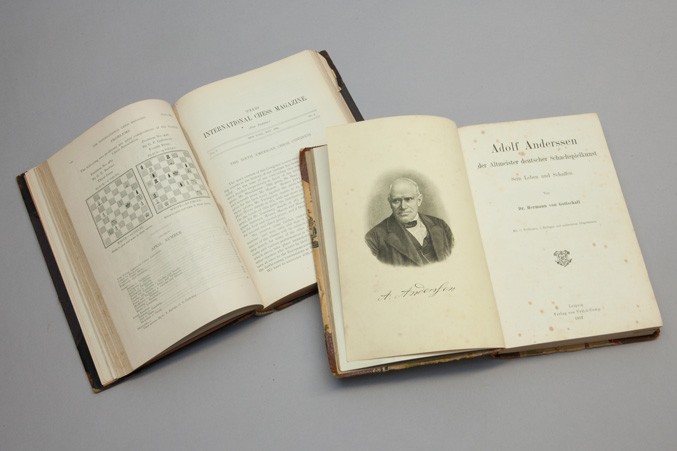

Fischer’s first source for chess books was the Brooklyn Public Library, whose collection he quickly exhausted. Fortunately by this time he had befriended Jack Collins, the founder of the legendary Hawthorne Chess Club, which would become Bobby’s second home. Collins had an extensive library and introduced Bobby to great players of the past including Wilhelm Steinitz and Adolf Anderssen. The two spent many an hour going through Steinitz’s The International Chess Magazine and Hermann von Gottschall’s work on Adolf Anderssen. Their influence on Fischer can be seen in his habit of transforming “museum piece” openings into dangerous weapons with Steinitz’s 9. Nh3 in the Two Knights one of the best known examples. This line, violating the well-known maxim “a knight on the rim is dim,” had scarcely been played since the 1890s when Fischer resurrected it in 1963.

Collins wrote of Bobby and his reading habits:

Bobby has probably read—more than ‘read’, rather, chewed and digested—more chess books and magazines than anybody else. This was no task; it was a pleasure, and it has made him the most knowledgeable player in history. Five to ten hours a day of reading and studying have been the rule, not the exception. And language has been no barrier.1

Bobby began building his library early in his career and by the late 1950s he owned close to one hundred books and several hundred magazines. His collection continued to grow until a 1968 move to Los Angeles forced him to sell much of his library. Once settled in his new home, Fischer started acquiring chess literature in earnest. Ron Gross, who had become friends with Fischer at the 1955 U.S. Junior Open Chess Championship and would remain close with him for almost thirty years, recalls visiting his apartment in 1970 and finding piles of books and magazines strewn everywhere, with only a narrow path allowing passage through the living room.

This new library became an important tool for Bobby in his march to the World Chess Championship in the early 1970s, and many of the items in the Fischer Library of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield from this time show heavy usage, particularly several issues of Chess Informant and study notebooks that Robert Wade prepared for Fischer’s Candidates matches against Mark Taimanov and Tigran Petrosian and for the World Championship challenging Boris Spassky. Wade compiled these notebooks by poring through chess periodicals and books, collecting hundreds of games by each of Fischer’s opponents. Today, with thousands of games by potential opponents available with one keystroke, it is easy to forget how much work it took Wade to create these files.

Bobby may have stopped playing after winning the World Championship, but he continued to keep abreast of new developments in chess. His mother Regina bought him subscriptions to magazines from around the world, particularly Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. The collection grew so large that by 1986 Bobby ran out of room at his apartment and had to rent space at a Bekins storage facility in Pasadena, California. When Fischer left the United States in the summer of 1992 to play the rematch of the 1972 World Chess Championship with Boris Spassky in Yugoslavia, he entrusted his friend Bob Ellsworth with making sure the payments on the storage space were kept up to date. The two, who had first met in the early 1970s through their mutual involvement in the Worldwide Church of God, were close even though Ellsworth was not a chess player. This relationship changed dramatically in late 1998, when Bobby suffered a tragedy brought on by a change in ownership of the storage facility.

Ellsworth, whose name was not on the lease, only learned of the change in ownership after a payment had been missed, and Fischer’s treasures scheduled for auction. He made a valiant attempt to buy everything back, spending over $8,000 of his own money, but in the end only partially succeeded, leaving Bobby devastated. Harry Sneider, Fischer’s former physical trainer who attended the auction with Ellsworth, arranged to have his son bring the twelve boxes of Fischer’s memorabilia that had been rescued to Budapest where Fischer was then living. Later, after Bobby’s death, the noted collector David DeLucia bought much of this material from Pal Benko, who was Fischer’s close friend for 50 years.

The Sinquefield Collection comprises most of Fischer’s other Bekins possessions. Primarily books and magazines acquired by Bobby between 1970 and 1992, it includes several items used in preparing for the World Championship match. These include a well-used copy of Chess Informant Volume 12, containing many handwritten notes and corrections and the aforementioned files that Robert Wade prepared on Mark Taimanov, Tigran Petrosian, and Boris Spassky. Supplementing Wade’s work was Fischer’s copy of the famous “Red Book” on Spassky. The last in the Weltgeschichte Des Schachs (World History of Chess) series, this hardback book with a red cover was Fischer’s inseparable companion during his preparations for the world championship match, and he is said to have played through and remembered every game in it.

His annotations, neatly handwritten in the margins are fascinating. Witness the following cryptic note to the game Spassky–Suetin, Soviet Union, 1967. After 1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Nc3 e6 4. d4 cxd4 5. Nxd4 Qc7 6. Be3 a6 7. Nb3 Nf6 8. f4 Bb4 9. Bd3 Fischer has written in the margin 9. …d5! This novel way of handling this variation where putting the Black pawn on d6 is the norm, was first employed in an analogous position by Adolf Anderssen in 1877, but seldom seen until the last game of the 1972 world championship match in Reykjavik which opened 1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 e6 3. d4 cxd4 4. Nxd4 a6 5. Nc3 Nc6 6. Be3 Nf6 7. Bd3 d5.

The single most important work in the Sinquefield Collection is a typewritten galley of an early version of My 60 Memorable Games with handwritten corrections by Bobby. Fischer spent four years writing and revising his classic work and much interesting material did not survive the final cut. The following is the first of two examples of Fischer’s preliminary text:

Game 32: Fischer-Tal

“Tal has an annoying habit of writing down the move he intends to play before making it. As a consequence his scoresheet is an eyesore. He usually write lemons down on the first draft, reserving the move he actually selects until somewhere around the fourth chicken scratch. Unfortunately, the temptation to glance at his scoresheet is overwhelming; I got excited when I saw him write down 20. …Ra5 21. Bh5 d5 (21. …d6 22.Rxd6!) 22. Rxd5 exd5 23. Re1+ wins outright.”

Only the variation survived the final cut for publication.

The next passage from Game 45: Fischer-Bisguier was completely eliminated from the final version of My 60 Memorable Games. However, Chess Life’s December 1963 issue published a similar note by Bobby:

“On the last occasion, referred to above, my opponent played 4. …Bc5!? alias the Wilkes Barre Variation. At that time I was quite unfamiliar with it and nearly laughed out loud at the thought of my opponent making such a blunder in a tournament of this importance! I was just about to let him just have it when I noticed that he had brought along a friend who was studying our game very intently. This aroused my suspicions: maybe this was a trap, straight out of the book. But a Rook is a Rook—so I continued with 5. Nxf7 and there followed 5. …Bxf2+! 6. Kxf2 Nxe4+ 7. Ke3 Qh4 and, somehow, I got out of the mess with a draw. I had no chance for first place and my trophy for the best scoring player under 13 was already assured, since I was the only one under 13!”

Fischer had begun writing My 60 Memorable Games in 1965, and it took four years for it to finally see publication. The conflict between Bobby’s desire to write the best book possible and his reluctance to provide information that might help his opponents undoubtedly prolonged the writing process.

These drafts, along with Fischer’s study materials in the Sinquefield Collection, allow unprecedented insight into the mind of the chess champion, exhibiting his intense attention to detail and remarkable analytical abilities. The Sinquefield Collection also includes Fischer’s own copies of publications about the 1972 World Championship match; chess periodicals; books inscribed to the champion by other famous players including David Bronstein, Anatoly Karpov, and Viktor Korchnoi; and other artifacts from post-1972; which together paint a complex picture of Fischer’s life in chess.

—IM John Donaldson, 2014

1 John W. Collins, My Seven Chess Prodigies (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1974), p.53.

About the Curators

Shannon Bailey, Chief Curator, World Chess Hall of Fame

Shannon Bailey is Chief Curator at the World Chess Hall of Fame. She most recently served as the Director of Institutional Giving at the Contemporary Art Museum Saint Louis. Prior to that, she was the Director of Art Galleries at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas.

In addition to her museum work, Shannon has taught university-level art history classes at Cleveland State University, Stephen F. Austin State University, and Saint Louis University. Shannon holds a Master of Arts in Art History and Museum Studies from the Case Western Reserve University/Cleveland Museum of Art joint program and a Bachelor of Arts in Art History and Museum Studies from Juniata College.

Emily Allred, Assistant Curator, World Chess Hall of Fame

Emily Allred is Assistant Curator at the World Chess Hall of Fame. Prior to working at the WCHOF, she was the Research Assistant in the American Art Department at the Saint Louis Art Museum and the Researcher and Collections Manager for the John and Susan Horseman Collection. Emily has contributed to publications for the two institutions. She has a Master of Arts in History and Museum Studies from the University of Missouri-St. Louis and a Bachelor of Arts in Art History and Communications from the University of Missouri-Columbia.

Boyhood Career

Furniture owned by Jack Collins, date unknown

Alpha Chess Clock owned by Jack Collins, c. 1957

Chess Set and Board owned by Jack Collins, date unknown

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

The furniture on view is from the living room of Jack Collins, a critical mentor of Bobby Fisher and a cofounder of the Hawthorne Chess Club, which he ran from his home. Jack met Bobby at the U.S. Amateur Open on Memorial Day weekend in 1956. Soon after, Bobby began spending time at Collins’ apartment, which eventually became a second home to him. They studied Jack’s extensive collection of chess books and analyzed and played countless games together. A photo of the two playing in Collins’ living room is on view in this exhibition.

This constant contact with Collins proved helpful to Fischer; in the second half of 1956 he won the U.S. Junior Chess Championship, tied for fourth in the U.S. Chess Open, and defeated Donald Byrne in the Third Lessing J. Rosenwald Trophy Tournament in a contest that would later become known as the “Game of the Century.” The following year he continued to excel, winning the 1957 U.S. Junior Chess Championship, the 1957 U.S. Chess Open, and the 1957/58 U.S. Chess Championship, all before reaching the age of 15.

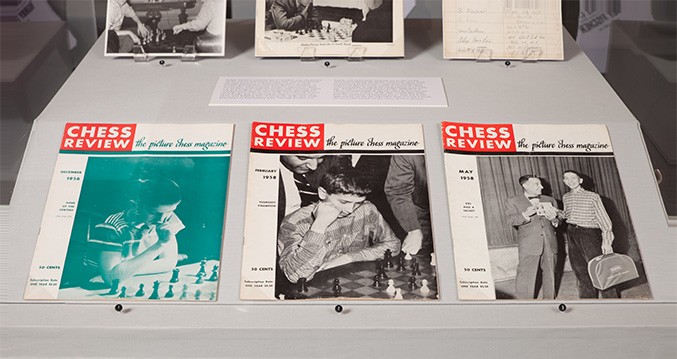

Chess Review Vol. 24, No. 12; Chess Review Vol. 26, Nos. 2 and 5

December 1956-May 1958

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

Chess Review Vol. 24, No. 12:

Young Bobby studies the game position prior to his daring queen sacrifice with 17. …Be6!! in his game against Donald Byrne at the Third Lessing J. Rosenwald Trophy Tournament. Shortly after the game ended, International Master Hans Kmoch annotated the game for the December 1956 issue of Chess Review. The noted chess journalist dubbed it the “Game of the Century”, writing, “The following game, a stunning masterpiece of combination play performed by a boy of 13 against a formidable opponent, matches the finest on record in the history of chess prodigies.”

Chess Review Vol. 26, No. 2:

The youngest-ever winner of the U.S. Chess Championship at age 14, Bobby Fischer is featured on the cover of Chess Review for his victory in the 1957/58 event. This qualified him to play in the Interzonal Tournament in Portoroz, Yugoslavia. More than half a century later Fischer still holds the record as youngest champion.

Chess Review Vol. 26, No. 5:

On the cover of this issue of Chess Review, a young Fischer beams after winning two round-trip plane tickets to Europe during his March 26, 1958, appearance on the CBS-TV program I’ve Got a Secret. During the show, he appeared before a panel of judges including Dick Clark, who was tasked with guessing Fischer’s secret based on the headline “Teenager’s Strategy Defeats All Comers.” Clark did not discover Bobby’s secret (that he was the U.S. Chess Champion), and he earned transportation to Europe, enabling him and his sister Joan to visit Moscow and travel to Yugoslavia for the Portoroz Interzonal Tournament. On the show Fischer mentioned that he learned to play the game at six, but only took it up seriously when he was nine.

Young Bobby Fischer and Jack Collins playing chess in his home

c. 1956-58

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

In his book My Seven Chess Prodigies, Jack Collins wrote that Bobby was a constant presence at his home at 91 Lenox Road in Brooklyn from the summer of 1956 to the summer of 1958. During this time, Fischer went from being rated 2200 to one of the best players in the world. While not a teacher in a formal sense, Collins was a valuable mentor who studied and played chess constantly with Bobby. The Hawthorne Chess Club, which was based in Collins’ home, attracted not only Fischer, but also other strong junior players including William Lombardy and Raymond Weinstein, who would soon be ranked among the best in the United States.

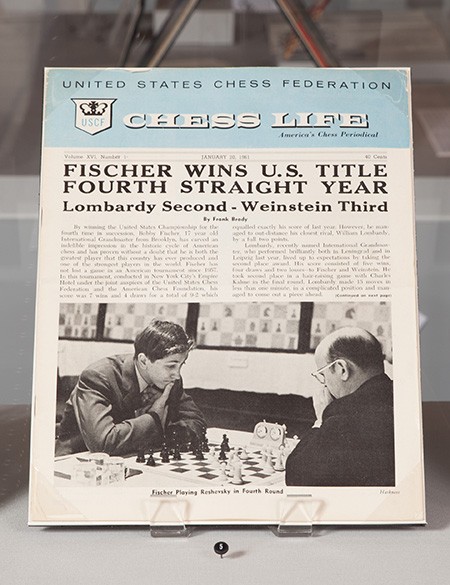

Chess Life Vol. 16, No. 1

January 20, 1961

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Fischer’s fourth straight win in the U.S. Chess Championship earned him a photo on the cover of the first issue of Chess Life to be published as a magazine. The storied chess publication had previously appeared in a newspaper format from 1946-1960. Fischer would eventually win all eight U.S. Chess Championships in which he competed, an accomplishment he would later describe as his proudest to Icelandic grandmaster and good friend Helgi Olafsson. In the 1963/64 event, Fischer had a historic 11-0 performance. His overall score of 74/90 in the U.S. Chess Championships (61 wins, 26 draws, 3 losses) is another record accomplishment that is unlikely to be matched.

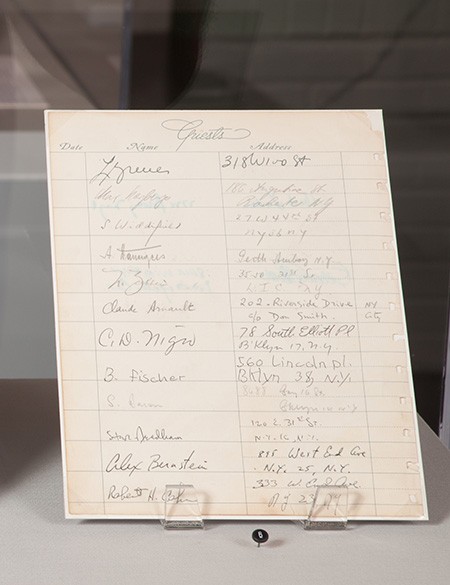

Manhattan Chess Club Sign-In Sheet

c. 1955

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

Showing the signatures of Fischer and his early chess teacher Carmine Nigro, this 1955 sign-in sheet from the Manhattan Chess Club bears witness to Bobby’s early entry into the New York chess scene. International Master Walter Shipman, one of the best chess players in the country in the mid-1950s, remembers that the two first visited the Manhattan Chess Club together in 1955. Shipman played against the 12-year-old Bobby in a series of blitz games at one second a move. Though he won two-thirds of them, he quickly realized that Fischer was quite a special talent.

The Manhattan, unlike the other great New York chess club, the Marshall, had no junior players as young as Bobby at the time. Club President Maurice Kasper made an exception for the prodigy and gave him a free membership as further encouragement at this early point of his career.

Fischer–Reshevsky Match

Letter from Harry Borochow to Walter Fried

August 14, 1961

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

National Master Harry Borochow served as the substitute referee for the adjourned portion of the 11th game of the Bobby Fischer–Samuel Reshevsky match. Here, he writes about the abrupt ending of the contest, and offers criticism of Fischer’s behavior. He supported the position of the organizers, believing that Fischer should have played at the rescheduled time for the 12th game. He states that Fischer had been informed in advance that the schedule had been changed.

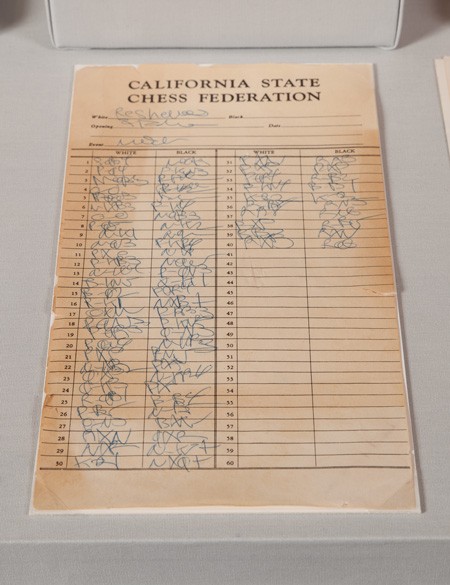

Bobby Fischer—Samuel Reshevsky, Round 11 Scoresheet

August 10, 1961

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

This score sheet records the eleventh, and what would become the final, game of the Fischer–Reshevsky match. This score sheet only shows the moves up to the adjourned position; the game actually went to move 57. Fischer would later include this as game 28 in My 60 Memorable Games.

Game 11 represented one more lost opportunity for Fischer, who, with a stronger performance, could have been up by two points by this point in the match. Games 3, 4, 6, 9, and 10 were relatively quiet draws. Bobby won game 2 cleanly, while the fifth game was closely fought. He lost game 7 on a one-move blunder, but Reshevsky was clearly better. These eight games leave Bobby one up, and in the remaining three he missed opportunities to improve his standing in the event.

Chess Review Vol. 29, No. 9

September 1961

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

Writers for the two national magazines, Chess Life and Chess Review, weighed in on the termination of the match, some taking the side of Fischer, while others supported that of the organizers. The former publication, the house organ of the U.S. Chess Federation, saw its young editor (and future Fischer biographer) Frank Brady try to stay officially neutral, but his article would ultimately be seen as endorsing Fischer’s opinion. Brady stressed the fact that the official announcement for the match had game 12 listed at 7:30 p.m. on August 12, and though Reshevsky’s requests for modifications in the playing schedule had been accommodated, Fischer’s opposition to playing the following morning instead had not been considered. Al Horowitz, founder of the independent periodical Chess Review, had a more nuanced approach. He examined Brady’s points, but also stressed that Fischer had been told of the time change for game 12 on August 3, and Fischer only objected a week later. By then the new schedule had already been published in the Los Angeles Times, and it would have been difficult to change the schedule again.

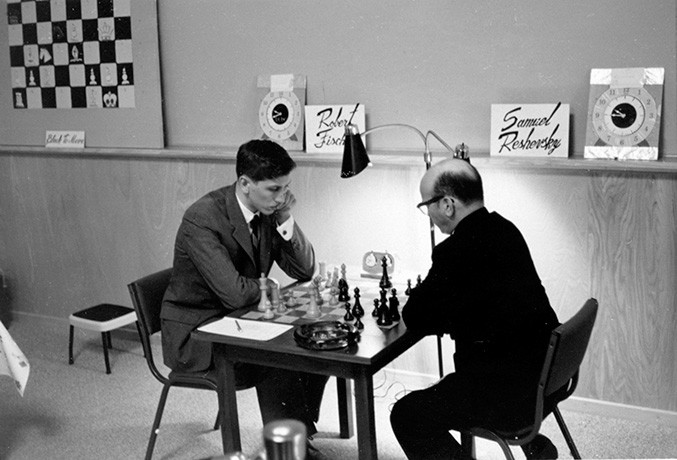

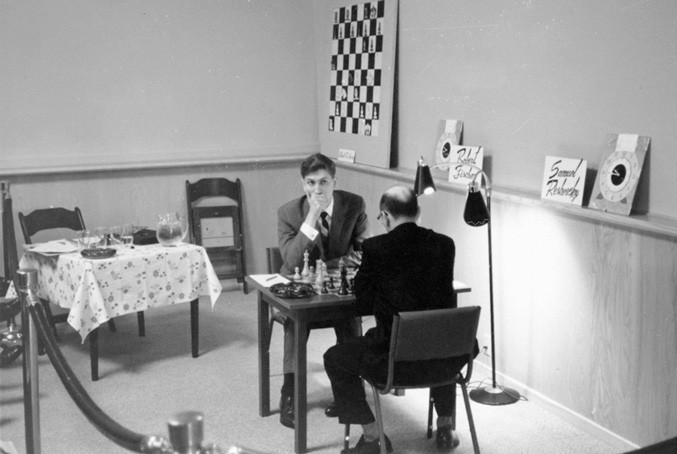

Bobby Fischer in thought after Samuel Reshevsky’s 10…Qa5 in game 6 of their match

1961

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

Never an opening expert, Samuel Reshevsky faced a serious challenge in how to counter Fischer’s habitual 1. e4. Normally Samuel would meet 1. e4 with 1. …e5, but Fischer was already a great expert on the Ruy Lopez. As a result, Reshevsky played the Accelerated Dragon opening the five times he played with the black pieces during this match. He lost the second game, but it was Bobby who varied in games 4, 6, 8, and 10. All of these games ended in draws, and Reshevsky could consider his experiment a success.

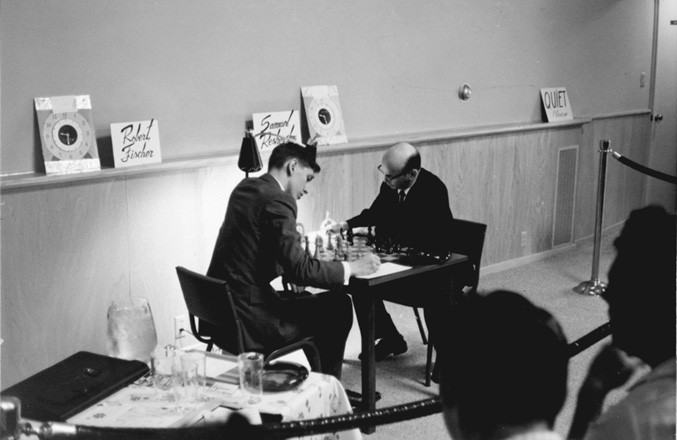

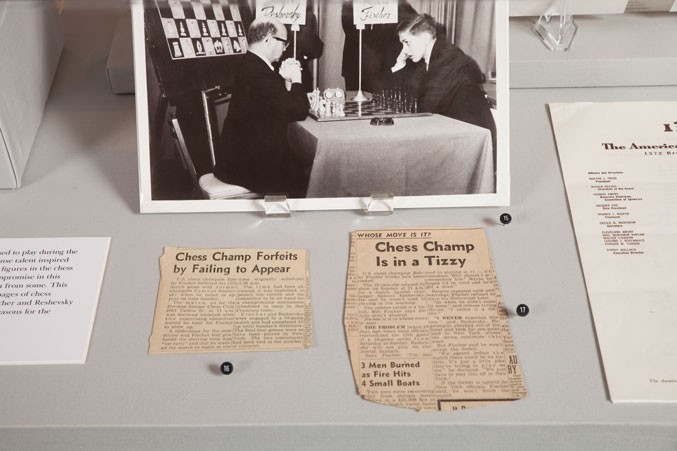

Bobby Fischer and Samuel Reshevsky in Game 6 of their 1961 Match

1961

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

For the only time in the match, Fischer won game 5 with the black pieces. He would later include the dramatic, closely-fought battle in his book, My 60 Memorable Games. Going into game 6 and leading 3-2, Fischer was eager to win, but the game ultimately ended in a draw.

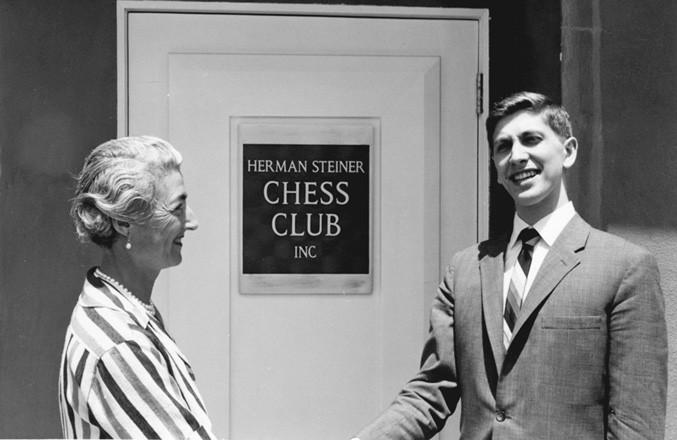

Jacqueline Piatigorsky and Bobby Fischer at the Herman Steiner Chess Club

1961

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Samuel Reshevsky Ponders the Position after 12. Qg4 in Game 6 of the 1961 Bobby Fischer—Samuel Reshevsky Match

1961

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

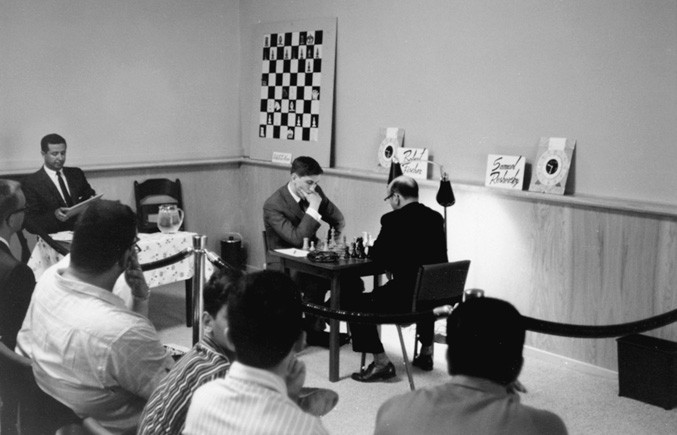

The Audience at the 1961 Bobby Fischer—Samuel Reshevsky Match Sponsored by Jacqueline Piatigorsky and the American Chess Federation

1961

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

The 1961 Bobby Fischer—Samuel Reshevsky Match Sponsored by Jacqueline Piatigorsky and the American Chess Federation

1961

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

These four photos, taken at the newly opened home of the Herman Steiner Chess Club in Los Angeles, capture the excitement elicited by the Fischer–Reshevsky match among West Coast chess fans. The first depicts 18-year-old Bobby with Jacqueline Piatigorsky, a skilled chess player herself, who was making her debut as a chess organizer and patron during the match.

Letter from Al Bisno to Morris Kasper and Walter Fried

August 21, 1961

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

Al Bisno, a president of the Manhattan Chess Club in the 1950s, expresses his disappointment in Fischer in this letter written after the end of the Fischer–Reshevsky match. Bisno had worked to secure financial backing and publicity for the match. Here, in a letter written during the peak of the controversy following the match, he condemns Fischer. Bisno suggests that Bobby receive no share of the cash prize and even goes so far as to demand he seek psychiatric help. Curiously, three years later Bobby and Bisno were again on good terms and the latter tried to arrange a match between Fischer and a top Soviet player.

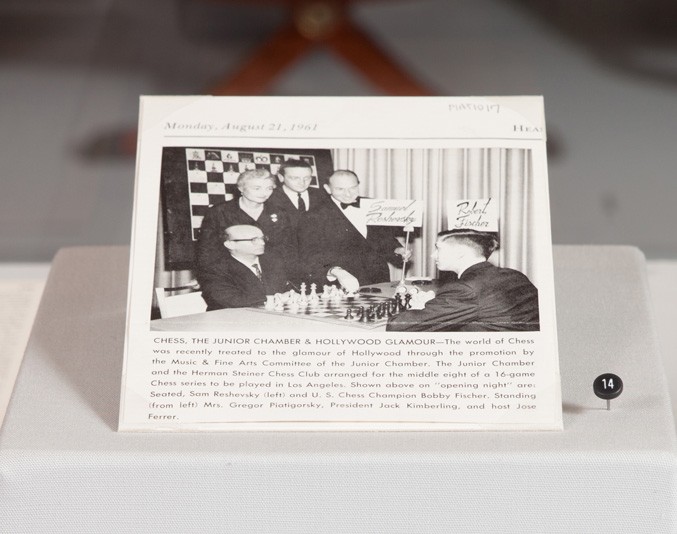

Chess, the Junior Chamber & Hollywood Glamour

August 21, 1961

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

Herbert Dallinger

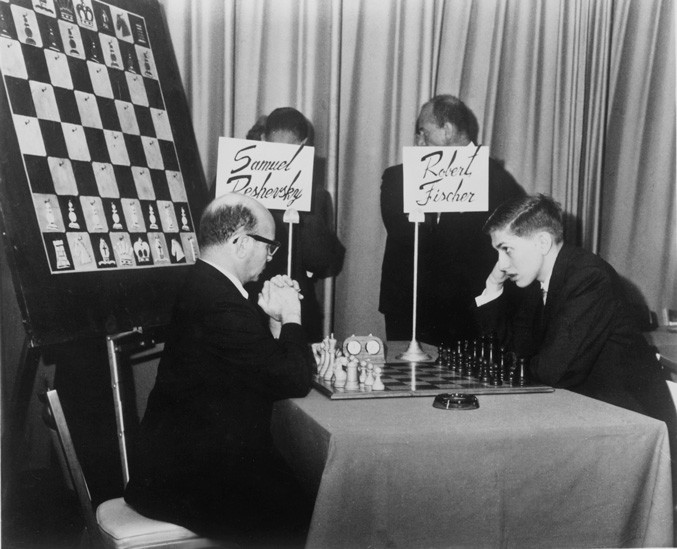

Samuel Reshevsky and Bobby Fischer at the 1961 Match

1961

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

Hosted by actor José Ferrer, the opening game of the Los Angeles half of the Fischer–Reshevsky match took place at the Beverly Hilton Hotel. Here the two players pose before the opening of the fifth game. The first four games of the match were held at the Empire Hotel in New York, under the auspices of the American Chess Foundation, and the next eight were scheduled to be held in Los Angeles, at the Beverly Hilton and the newly-opened Herman Steiner Chess Club, which was housed in a building designed by noted architect Frank Lloyd Wright, Jr.

Though separated by decades in age, Fischer and Reshevsky were both prodigies known for their unconventional childhoods as well as their chess skills. Fischer sometimes experienced a lack of supervision from his mother as a young child; however, Reshevsky supported his family through an endless series of simultaneous exhibitions in Europe and the United States. He did not attend school, and at one point his parents were forced to appear in District Court in Manhattan facing charges of improper guardianship.

“Chess Champ Forfeits by Failing to Appear”

Los Angeles Times, August 14, 1961

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

“Chess Champ Is in a Tizzy”

Unknown Publication, c. 1961

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

The chess world was a small and insular place in 1961. Jacqueline Piatigorsky’s good friend and fellow U.S. Womens Chess Championship competitor Lina Grumette used her skills as a public relations expert to ensure that the Los Angeles section of the match was well-covered in both the local and national press. Grumette, herself a strong women’s chess player, would also later gain fame as a friend and caretaker of Fischer, providing him housing when he moved to California and encouraging him in his run for the 1972 World Chess Championship.

The fallout of the premature ending of the Fischer–Reshevsky match was covered in the mainstream press as well as in chess publications. In this article Fischer declared that he and Reshevsky had previously agreed that there would be no forfeits in the match. Of the decision to declare game 12 a forfeit, he said, “It’s just a little joke they’re [the organizers] trying to play on me.” Though the end of the match was acrimonious, both Jacqueline Piatigorsky and Al Bisno, two of the key organizers of the match, would go on to invite him to later competitions they held.

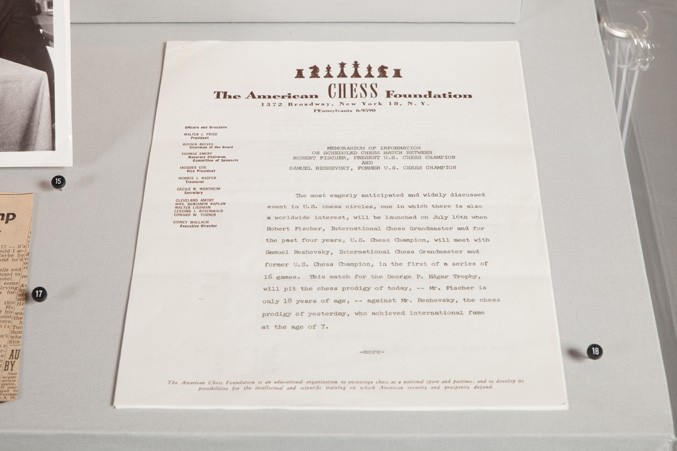

Memorandum of Information on Scheduled Chess Match Between Robert Fischer, Present U.S. Chess Champion and Samuel Reshevsky, Former U.S. Chess Champion

June 28, 1961

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

Billed as a battle between two players representing the past and future of American chess, the Fischer–Reshevsky match pitted “the chess prodigy of today…against the chess prodigy of yesterday”. Chess players around the world greeted the announcement that Samuel Reshevsky and Bobby Fischer would play a match with great interest. The 18-year old Fischer had age and recent results on his side, but most grandmasters expected the 49-year-old Reshevsky to win for one simple reason—he had played many matches and never lost a single one. Prior to this contest, Fischer and Reshevsky had met six times with four draws and a win each. Reshevsky led the match at its termination.

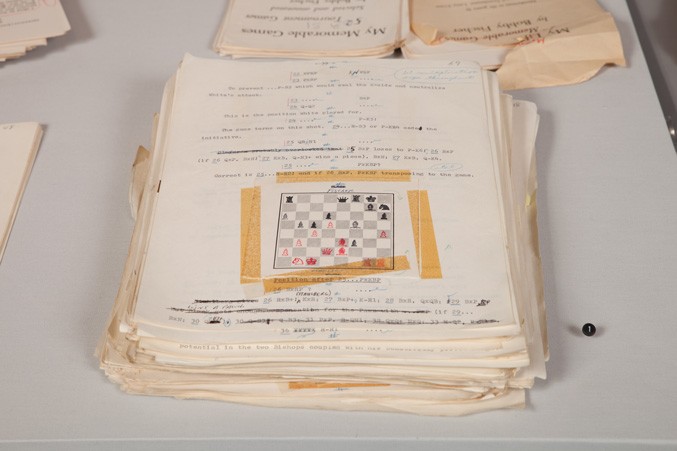

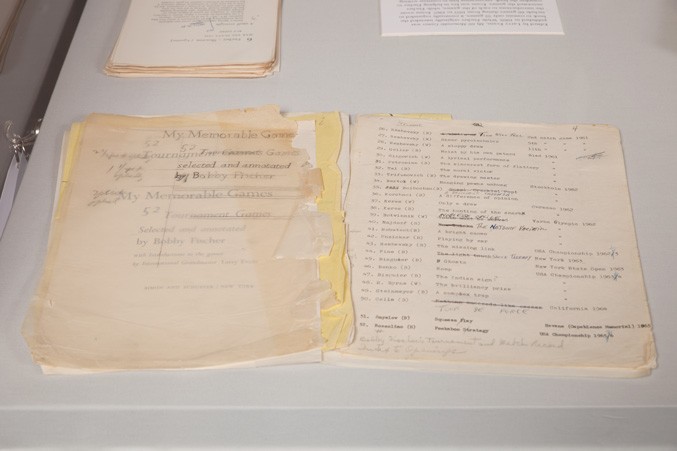

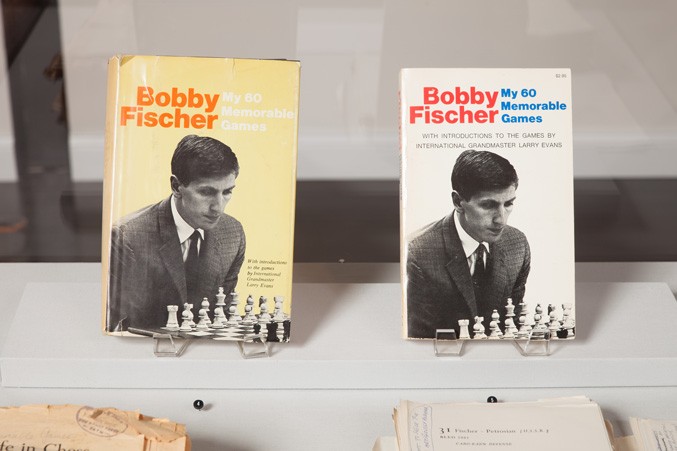

Manuscripts of My 60 Memorable Games

Bobby Fischer and Larry Evans Draft of My 60 Memorable Games with Editing Notes

March 23, 1966

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

Bobby Fischer and Larry Evans Draft of My 60 Memorable Games with Editing Notes

March 23, 1966

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

This early draft of what would later become My 60 Memorable Games ends at game 52, Fischer’s victory over fellow Grandmaster Nicolas Rossolimo at the 1965 U.S. Chess Championship. In the years to come, Bobby would update the book and add eight additional games bringing the total to 60. Fischer’s brilliant win over Soviet grandmaster Leonid Stein at the Sousse Interzonal Tournament in Tunisia, which ended in November 1967, is the last game in the final version of the book.

Bobby Fischer and Larry Evans Draft of My 60 Memorable Games with Editing Notes

January 14, 1967

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

When My 60 Memorable Games was finally published in 1969, it immediately won acclaim as one of the greatest games collections of all time. Combining fantastic games and brilliant analysis, the book is also distinguished by its lively prose. Though Fischer would annotate a few games after the publication of My 60 Memorable Games, including light notes to most of his encounters in a famous blitz tournament in Yugoslavia in 1970, he would never again undertake such a massive project.

Best games collections published prior to My 60 Memorable Games followed a strict template, offering only wins by the author against elite opponents in serious tournaments. However, Fischer deviated from this pattern, including many great victories, but also nine draws and three losses. Most are from major events, but Fischer played one in a simultaneous exhibition and another is a skittles game (a casual game played for fun). Fischer’s competition ranges from world champions to amateurs. Rather than simply recording his most notable wins, the publication is a collection of games that were most meaningful to Fischer.

Bobby Fischer and Larry Evans My 60 Memorable Games

1969

Simon and Schuster

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

Much anticipated in the chess community, My 60 Memorable Games received universally positive reviews. The February 1969 issue of Chess Life announced the U.S. Chess Federation would accept orders for the hardback book. The book was reprinted several times in 1969, and a paperback edition came out later in the year. The paperback version corrected an error in the score of the Bobby Fischer—Milan Matulovic match. Fischer’s previous book, Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess, is the all-time best selling chess book, selling over one million copies.

My 60 Memorable Games was translated into many languages, including Russian. The latter irked Bobby because the royalties the Soviets offered were only payable in rubles, which weren’t convertible to U.S. dollars at the time. Published in 1972, the Russian language version is faithful to the original, but also offers a 5-page introduction by Vasily Smyslov and a 37-page analysis of Fischer’s style by Grandmaster Alexey Suetin.

1971-1972 Study Materials

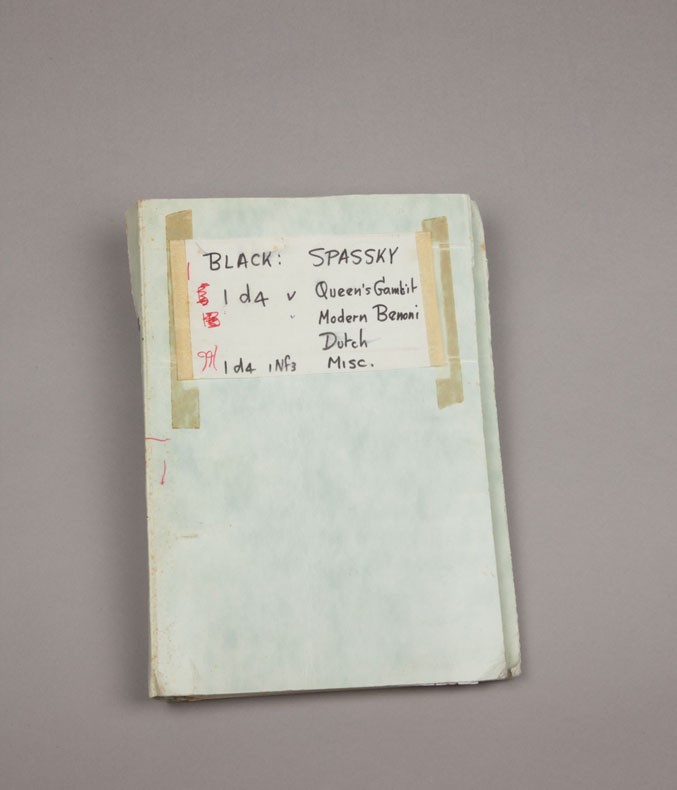

Robert Wade

Black: Spassky 1 d4 v… 1972

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

Fischer’s comments about this game between Viktor Korchnoi and Boris Spassky from the1960 U.S.S.R. Chess Championship suggest Bobby may have considered surprising Boris with 1. d4 during the World Chess Championship match. This note indicates Fischer may have prepared many novelties for the World Chess Championship that he was ultimately never able to use.

1. d4 d5 2. c4 dxc4 3. Nf3 Nf6 4. e3 Bg45. Bxc4 e6 6. 0–0 a6 7. Qe2 Nc6 8. Rd1 Bd69. h3 Bh5 10. e4

Here Fischer gives 10. Nc3! 0–0 (or 10…Qe711. e4 e5 12.Bg5!) 11. g4 Bg6 12. e4 Bb413. d5!.

Unlike the material Robert Wade prepared about Tigran Petrosian, whom Fischer faced in the 1971 Candidates Match, there were almost no written comments in the booklets of Spassky’s games. By the time Wade had finished compiling these notebooks, Fischer may have already received an advance copy of the “red book,” containing 355 of Spassky’s games in one volume, a more convenient format for study.

The University of British Columbia hosted the Candidates Match through the efforts of Canada’s Zonal President John Prentice. American chess has had several great sponsors including Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield and Jacqueline and Gregor Piatigorsky, but Canada has had only one—John Prentice. Affectionately known as “Plywood Prentice” for the timber business he founded in British Columbia after he left his native Austria shortly before World War II, Prentice sponsored Fischer’s first Candidates Match.

Evgeni Vasiukov was one of the Soviets that Fischer played blitz with during Bobby’s only visit to the Soviet Union in 1958. Although already a strong player, Vasiukov was not well-known outside the U.S.S.R. at the time. It would have been reasonable to expect that Bobby wouldn’t remember him, but this was not the case. Fischer later not only recalled playing Vasiukov in blitz games, he started rattling off the moves of several of them.

The venue for the Fischer–Taimanov match was unsettled for some time, as Bobby hoped to play in the United States and Taimanov the Soviet Union. Finally, Vancouver was chosen as neutral ground. The Fischer mania that was to strike the United States in 1972 did not exist a year earlier. While the crowds were respectable for this match, there were never more than 100 spectators. Among them was the future grandmaster Peter Biyiasas who served as a wall boy for one game and who would host Fischer in San Francisco ten years later.

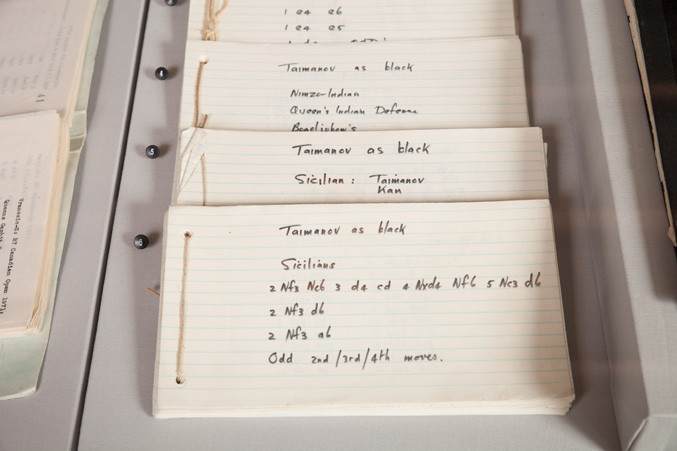

Robert Wade

Taimanov as Black: Sicilians, 2 Nf3 Nc6, 2 Nf3 d6, 2 Nf3 a6, Odd 2nd/3rd/4th Moves

1971

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

In a 2012 interview with the Russian website Chess News, Grandmaster Evgeni Vasiukov, Taimanov’s second for the match, blamed malnutrition for the lopsided score in the1971 Candidates Match. According toVasiukov, Taimanov didn’t eat properly during the competition, preferring to save his meal money to buy Western goods unavailable in the Soviet Union. Vasiukov acknowledges Fischer was the stronger player, but argues that the final score should have been closer, a belief Fischer supported.

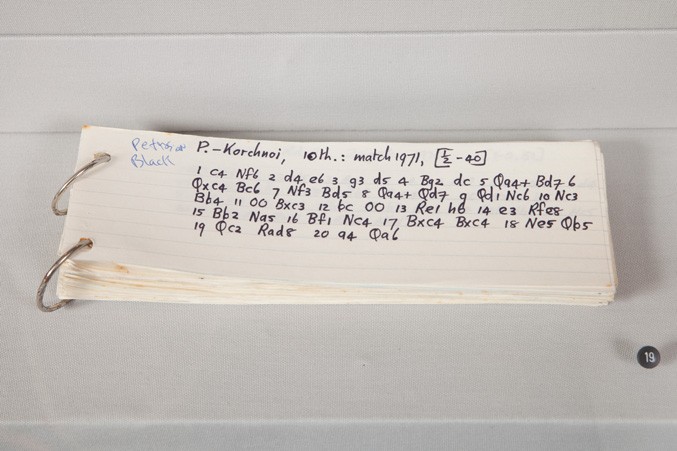

Robert Wade

Petrosian White: W12—W20

1971

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

In this page from a study notebook, Bobby notes the improvement 7. …Nxc3! after 1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nf3 b6 4. Nc3 Bb7 5. a3d5 6. cxd5 Nxd5 7 .e3. Petrosian never got a chance to employ his favorite anti-Queen’s Indian system, but something analogous to Fischer’s suggested improvement (7. …Nxc3!) occurred in game 8 where after 1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nf3 d5 4. Nc3 c5 5. e3 Nc6 6. a3Ne4 7. Qc3 Black played 7. …Nxc3. Fischer exhibited a strong preference for flexible, dynamic pawn structures to static ones and liked playing against hanging pawns.

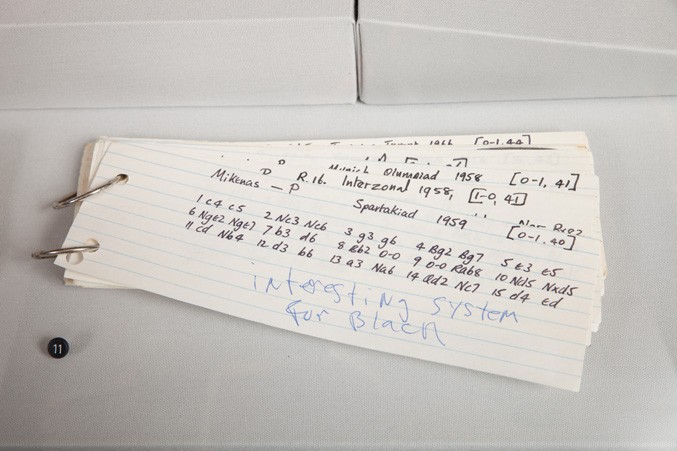

Robert Wade Petrosian Black: B27—B31 1971 Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

This game opens 1. c4 c5 2. Nc3 Nc6 3. g3g6 4. Bg2 Bg7 5. e3 e5 6. Nge2 Nge7 7. b3d6 8. Bb2 0–0 9. 0–0 Rb8 10. Nd5 Nxd5 11. cxd5 Nb4 12. d3 b6 13. a3 Na6 14. Qd2Nc7 15. d4 exd4.

In this notebook, Fischer comments that Petrosian employs an “interesting system for Black.” Indeed, after the more or less forced sequence 16. exd4 Ba6 17. Rfe1 Bxe2 18. Rxe2Nb5 19. dxc5 Bxb2 20. Qxb2 bxc5, Petrosian, playing as Black, had a clear positional advantage due to the superiority of his knight over White’s bishop.

Fischer (as Black) had defeated Petrosian in the 1970 U.S.S.R. vs. the World match with the variation starting with 5. …e6. Fischer was fond of meeting 1. c4 with 1…c5 at this stage of his career, and he may have been looking for a line that stayed close to home and sidestepped any improvements Petrosian planned after 5. …e6. The chance to play one of Petrosian’s weapons against him would have supplied an extra psychological benefit. This line did not appear in the match as Petrosian opened 1. d4 in game 2, 1. Nf3 and 2. b3 in game 5 and again 1. d4 in game 6. The closest it came to occurring was game 4 which opened 1. c4 c5, but Petrosian varied with 2. Nf3.

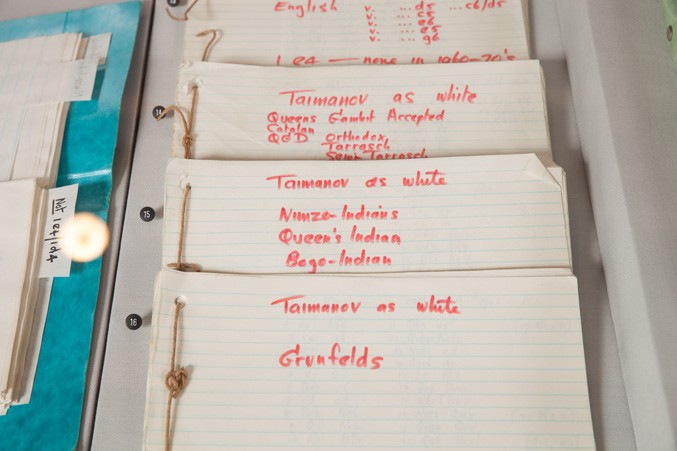

Robert Wade

Taimanov as White: Queen’s Gambit Accepted, Catalan, QGD, QP; Nimzo-Indian’s, Queen’s Indian, Bogo-Indian; Grunfelds

1971

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

International Master Robert Wade was a perfect researcher for Fischer. Born on a farm in Dunedin, New Zealand, Wade won three national titles before moving to England in the late 1940s. A European base was a necessity for a budding chess professional at the time. He won several national championships in his adopted homeland and played on its Olympiad team on six occasions. However, he is best known for his role as the chess editor at Batsford Publishing in the 1960s and 70s. The firm produced several groundbreaking books on different openings that set new standards and the high quality was in part due to diligent research. Wade’s tremendous library of books, periodicals, and tournament bulletins made this possible. It was the latter two that were particularly useful in building up the notebooks on Bobby’s opponents.

Organized by opening, each notebook contains hundreds of games, representing an incredible amount of time expended. The material proved helpful to Fischer, who made the notebooks his own by personalizing them with written observations and analytical notes. Nevertheless, some were more useful than others; during the match with Taimanov only three openings were played. Bobby opened 1. e4 each time he was White and all three games entered into the Taimanov variation of the Sicilian. Mark Taimanov also stuck to his guns, opening 1. d4 each time he was White. The first two times Bobby answered with the King’s Indian, but in both games White reached promising positions so he switched to the Grunfeld for the final game. This meant that much of the work Wade did was not particularly helpful for this match, but some of it might have proved inspirational later in the World Chess Championship cycle.

Near the end of the Palma de Mallorca Interzonal in 1970, Fischer and International Master Robert Wade made an agreement whereby the latter would be hired to research the games of Bobby’s opponents in the Candidates Matches and World Chess Championship. Ed Edmondson, the United States Chess Federation executive director at the time and Fischer’s de facto manager in1970-1971, took care of the arrangements.

Mark Taimanov, the Russian grandmaster and his first opponent in the matches, was, like Fischer, a qualifier from the 1970 Interzonal. A former Soviet champion, he was considered to be an underdog against Fischer in the first round of the Candidates Matches. Nevertheless, the final score of 6-0 was unexpected. It masks the fact that Taimanov consistently got decent positions out of the opening and early middlegame only to get outplayed or blunder later in the games.

Robert Wade

Petrosian White: W4—W11

1971

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

Here, Fischer makes a note that Robert Wade has inadvertently transposed the names of the players. This was a rare slip by the English International Master, who made few mistakes while preparing these study materials. Today a computer database would produce the information instantly, but Wade recorded the games by hand, consulting hundreds, if not thousands of periodicals, bulletins, and books.

1972 World Chess Championship

Chess Pieces from Game 3 of the 1972 World Chess Championship

1972

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

These chess pieces, created in the familiar Staunton style, bear witness to one ofthe most important games in the most famous World Chess Championship match. Fischer demanded that a Staunton set from Jaques of London be used for the game. Jaques of London is a well-known manufacturer of chess equipment. When the Staunton set, named for mid-nineteenth century chess great Howard Staunton, was first manufactured, Jaques of London maintained exclusive manufacturing rights. Eventually the set would become the standard for elite tournament play. Each of the pieces in the set on display is hand carved and lead weighted.

With them, Fischer defeated Spassky for the first time in his career, turning the momentum of the match. Had Fischer, trailing 0-2, lost game 3 of the World Chess Championship, he may have quit the match entirely. Prior to this game Fischer had not beaten Spassky and his lifetime score, excluding the second game forfeit, was four losses and two draws in six games. Bobby played to win as evidenced by his use of the double-edged Modern Benoni opening and adoption of the seldom seen (before or since) 11. …Nh5!?. Fischer’s unconventional strategy worked, and he ultimately won the game, turning the tide of the match. The pieces are set to display a position from the third game of the match, when Fischer played this surprising move.

Signed by Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer, this is one of ten wooden boards created for their 1972 World Chess Championship match. Originally, organizers commissioned a mahogany chess table with inlaid marble squares for the two competitors to use in the match. However, the squares were not regulation size. This displeased Fischer, who was very particular about the equipment he used in play. Organizers commissioned ten handmade wooden boards, from which Bobby would pick one for use in play. Icelandic chess officials expected Fischer to sign the remainder, which they then hoped to sell to offset some of the expenses of the match. Fischer initially balked, unwilling to sign anything that could be sold and unhappy with the width of the border of the chess board. He ultimately signed this board, which was not used in the match.

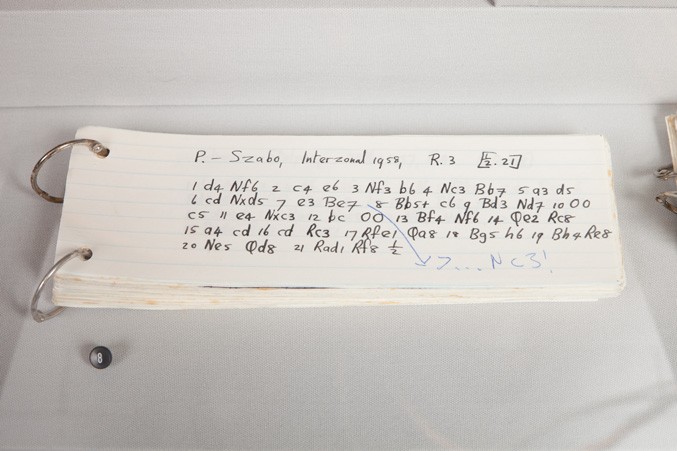

Eduard Wildhagen

Weltgeschichte des Schachs Lieferung 27, Boris Spassky:355 Partien History of Chess Part 27, Boris Spassky: 355 Matches

1972

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

Bobby Fischer is said to have memorized each of the 355 games in this volume, which totaled over 14,000 moves. The last volume in a series of books produced by the German publisher Eduard Wildhagen on great players of the world, it contains unannotated games by Spassky, with a diagram illustrating the progress of the game every five moves. This copy includes handwritten notes from Fischer, analyzing Spassky’s games. The book was a key aid in his preparations for the World Chess Championship match against Boris Spassky.

Fischer received an advance copy of the book from the publisher in December 1971. In a New York Times article detailing Fischer’s preparations for competing against Spassky published on March 31, 1971, Martin Arnold made a joking reference to it being referred to as the “big red book” to distinguish it from Quotations from Chairman Mao, which was known as the “little red book” of the time. Arnold further wrote that “training for the 6-foot, 2-inch, 29-year-old challenger consists of studying the Spassky red book, which he takes with him to the Grossinger [resort] dining room. He normally eats alone at a table while studying the book or playing with a chess set.”

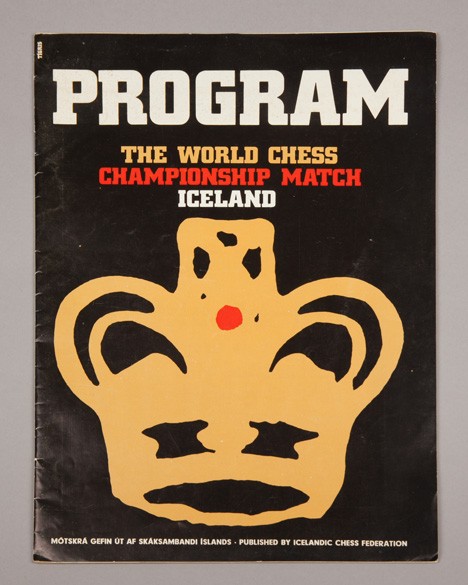

Program: The World Chess Championship Match, Iceland

1972

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

Attendance for Fischer’s first two matches in Vancouver and Denver was modest, but the turnout for the final Candidates Match in Buenos Aires was enormous. The World Chess Championship attracted a previously unmatched level of enthusiasm among the American public that has not been bested since. Television, magazines, and newspapers made it the leading news story of the summer of 1972. Displayed here is Fischer’s own copy of the program for the historic match.

Bobby Fischer’s Library

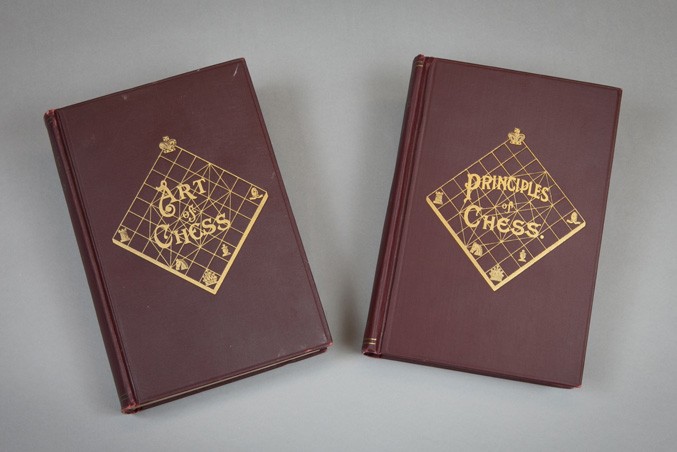

James Mason

The Art of Chess, Fourth Edition, Revised and Enlarged

The Principles of Chess in Theory and Practice, Fourth Edition, Revised and Enlarged

1914

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex SInquefield

Fischer’s love for old-time chess is evident in his ownership of these two books by James Mason, an Irish-born player prominent in the 1880s. Fischer explained his attraction to this material in a letter to Larry Evans dated September 15, 1963. He stated, “I am mainly occupying my time by studying old opening books and believe it or not I’m learning a lot! They don’t waste space on the Catalan, Reti, King’s Indian reversed and other rotten openings.”

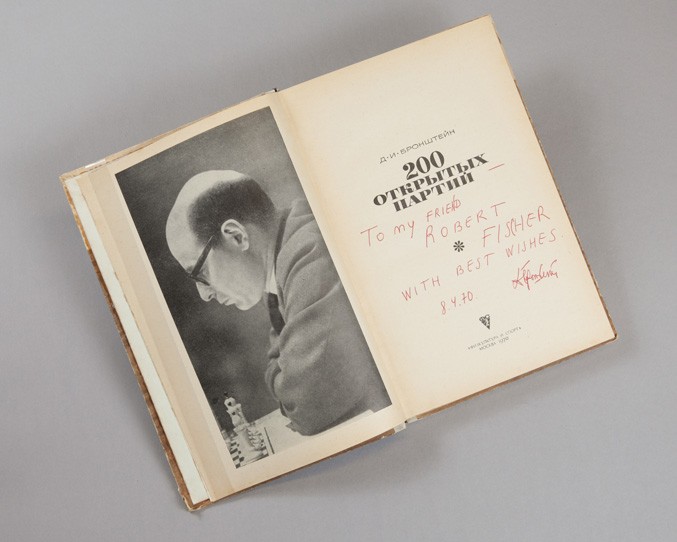

David Bronstein

200 открытых партий

200 Open Games

1970

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

Though Fischer hated the Soviet chess establishment, claiming that teams from the U.S.S.R. had colluded to defeat him in the 1962 Candidates Tournament, he had good relations with some of the individual players, among them David Bronstein. Here, Bronstein has inscribed his book 200 Open Games to Fischer.

Left: William Steinitz, Editor

The International Chess Magazine Vol. 5, No. 1-12

January-December 1889

Right: Dr. Hermann von Gottschall

Adolf Anderssen der Altmeister deutscher Schachspielkunst

Adolf Anderssen Great German Chess Player of the Past

1912

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

Jack Collins introduced Bobby to the work of William Steinitz, the first world champion. Collins and Fischer shared many hours playing through games from Steinitz’s The International Chess Magazine, which was published in the 19th century. Collins, writing in My Seven Chess Prodigies, noted that this journal “provided us with grand old games and insights into the frightening intellect and acid pen of the ‘Father of Modern Chess.’” Steinitz was a profound opening analyst, as was Bobby, and the latter adopted several of his pet lines including 9. Nh3 in the Two Knights Defense, 3. d4 followed by 4. e5 and 5. Qe2 in the Petroff as well as 5. d3 in the Ruy Lopez. Steinitz, like Bobby Fischer, is an inductee of both the U.S. and World Chess Halls of Fame.

Unlike other 20th-century world chess champions, Fischer was intimately acquainted with the games of Adolf Anderssen, a renowned player of the mid-19th century, but little-studied in the 20th. As Collins wrote in his book My Seven Chess Prodigies, “I once lent a brand-new copy of Adolf Anderssen, by Dr. Hermann von Gottschall, to him. Some weeks or months later he returned it, and I had good reason to believe he had worked over every game and note in it–all 751 games in the main section, plus 80 problems by Anderssen in another section!”

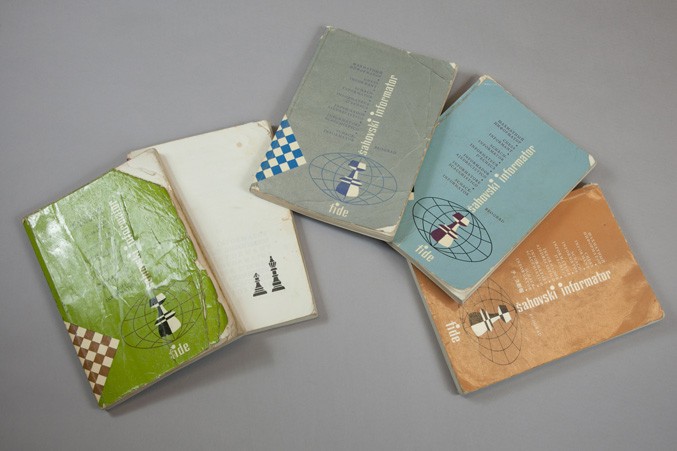

Sahovski Informator Vol. 12, 14, 15, and 27

Chess Informant Vol. 12, 14, 15, and 27

1972-1979

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

The Yugoslav publication Sahovski Informator (or Chess Informant, as it is known in North America) first appeared in 1966. Bobby Fischer was among its first champions. He held such a high opinion of it that when analyzing with participants in a U.S. Junior Closed Chess Championship around 1970, he advocated they buy it before his own book My 60 Memorable Games. Fischer also annotated ten of his games for Chess Informant between 1968 and 1970, further evidencing the esteem in which he held this publication. The wear on these volumes shows the frequency with which he used them for study.

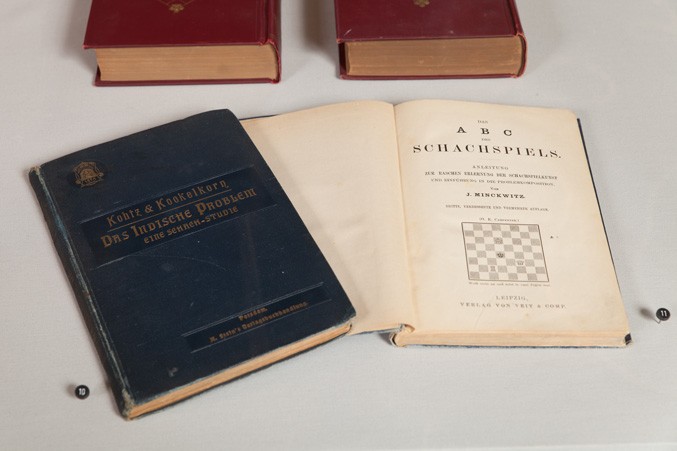

Left: Johannes Kohtz,

C. Kockelkorn Das Indische Problem: Eine Schach-Studie

The Indian Problem: A Chess Study

1903

Right: J. Minckwitz

Das ABC des Schachspiels: Anleitung zur Raschen Erlernung der Schachspielkunst und Einführung in die Problemkomposition

The ABCs of Chess: Rapid Guide to Learning the Art of Chess and Introduction to Composition Problems

1897

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

Though many serious chess players do not study chess problems, Bobby was eclectic in his reading habits and was known to enjoy solving them. However, more often he contemplated endgame studies put to him by his lifelong friend Pal Benko. While these volumes are rather obscure, they are not surprising to find in Fischer’s library.

1970 Tournaments and 1971 Candidates Matches

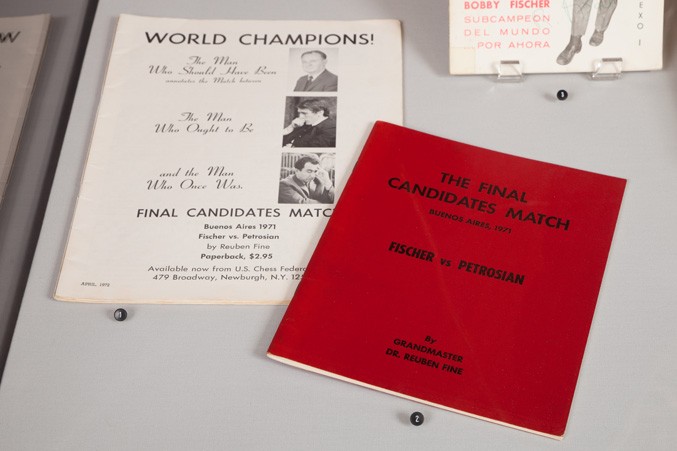

Left: Fine, Fischer, Petrosian Advertisement

Chess Life & Review, Vol. XXVII No. 4

April 1972

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

Right: Reuben Fine

The Final Candidates Match: Buenos Aires, 1971

1971

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

Fine, Fischer, Petrosian Advertisement: This classic advertisement for Reuben Fine’s booklet exploring the Bobby Fischer–Tigran Petrosian Candidates Match features images of each of the competitors, as well as the author. While the description of Fine as the man who should have been champion is exaggerated, (he did tie for first at AVRO 1938 with Keres but chose not to play in the World Championship tournament in 1948), Fischer and Petrosian’s descriptions were accurate.

The Final Candidates Match: This publication, advertised in the pages of Chess Life & Review, is Grandmaster Reuben Fine’s last serious work. He would later go on to write a book about Fischer’s 1972 World Chess Championship match that received universally negative reviews. Fine, an inductee to the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, is remembered for not only being a great player but also for writing several excellent books including Basic Chess Endings, The Ideas Behind the Chess Openings, and his best games collection A Passion for Chess.

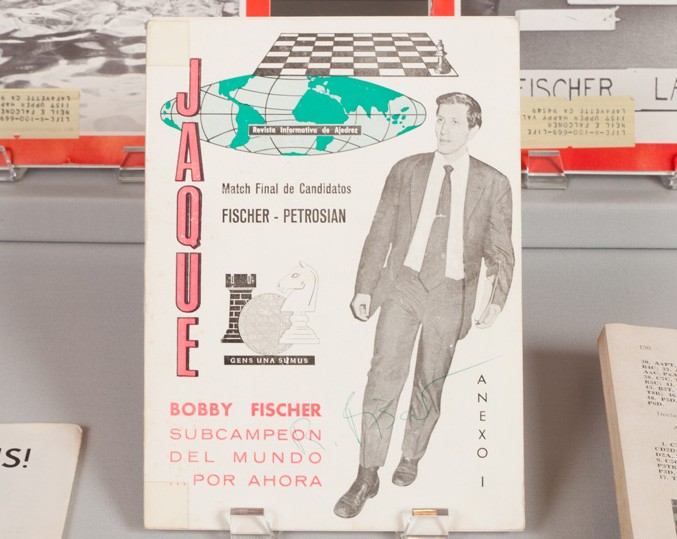

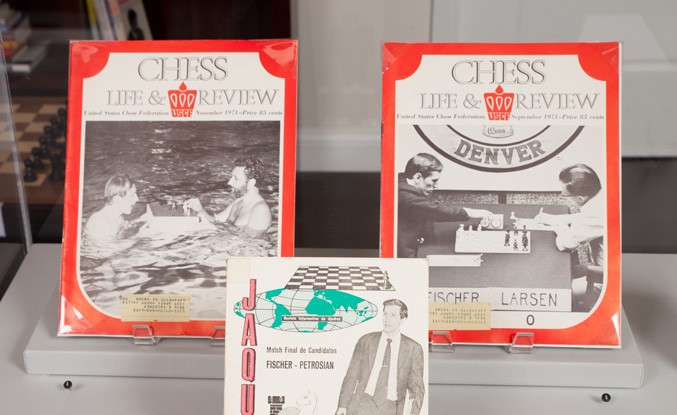

Jaque: Campeonato del Mundo Match Final de Candidatos Fischer—Petrosian, Buenos Aires, October 1971

Check: World Championship Final Candidates Match Fischer—Petrosian, Buenos Aires, October 1971

1971

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

Tigran Petrosian represented Fischer’s most difficult opponent in the 1971 Candidates cycle. Aben Rudy, a friend of Fischer’s and interviewee for the audio tour for this exhibition, remembers a meal he shared with Bobby and his old mentor Jack Collins shortly before the Petrosian match. Rudy expected Bobby to be brimming with confidence, as he had just defeated Mark Taimanov and Bent Larsen by a combined score of 12-0, while Petrosian had barely gotten past Robert Hubner and Viktor Korchnoi. However, Bobby explained that Petrosian was a much tougher opponent. For the first five games of the Candidates Match, Fischer and Petrosian were tied. Later Fischer would win four games in a row.

While the matches with Taimanov and Larsen had relatively modest attendance, the Candidates Final in Buenos Aires, Argentina, at the Teatro San Martin had over a thousand overflow spectators who could only watch from the lobby. The Spanish magazine Jaque published a special edition devoted to the Candidates Match between Fischer and Tigran Petrosian, containing not only detailed analysis of the games, but many interesting photographs of Bobby that have never been reproduced elsewhere.

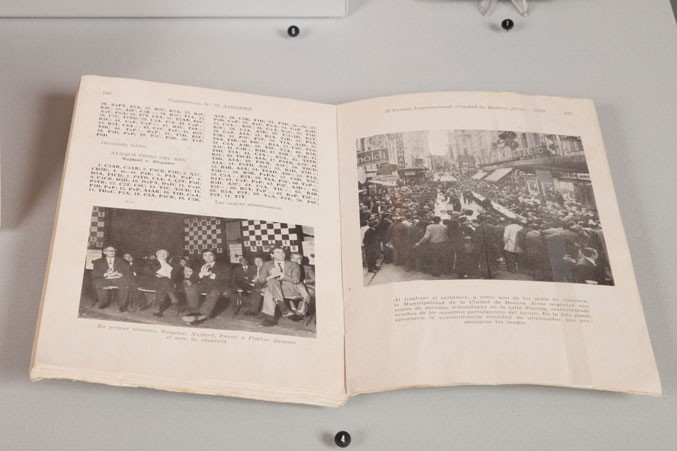

Suplement No. 29 de la Revista AJEDREZ: II Torneo Internacional “Ciudad de Buenos Aires”

Supplement No. 29 to CHESS Magazine: II International Tournament “City of Buenos Aires”

November 1970

Editorial

Sopena, Argentina

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

Buenos Aires 1970 was one of Fischer’s greatest tournament triumphs as he scored 15 out of 17 to finish three and a half points ahead of the field, which included former World Chess Champion Vasily Smyslov. There, Fischer not only took part in the tournament, but also participated in a large open air exhibition match. A special supplement of the Argentine magazine Revista AJEDREZ covered both the match and the exhibition.

Left: Chess Life & Review Vol. 26, No. 11 November 1971

Right: Chess Life & Review Vol. 26, No. 9 September 1971

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

Larry Evans, Fischer’s good friend, analyzes with him in a pool at Grossinger’s Resort in this playful photo on the cover of Chess Life & Review. Bobby had a long relationship with Grossinger’s Resort in the Catskill Mountains, about 100 miles northwest of New York City. When he won his first U.S. Chess Championship, the resort awarded Bobby a 10-day all expenses-paid stay. Later Bobby returned to the resort to prepare for his match against Tigran Petrosian in 1971. Fischer did not have a second at his match with Mark Taimanov. The reasons for this are varied. Though the U.S.C.F. was prepared to pay for a second, Fischer wanted Svetozar Gligoric, but the Yugoslav had prior commitments. Larry Evans was another choice for the Taimanov match but couldn’t meet Fischer’s requirement not to bring his wife or engage in journalism. Instead Evans helped him prepare beforehand. This was likely more helpful as Bobby never depended on others for opening choices and preferred to work on his adjournments alone.

Fischer’s match with Bent Larsen was held at Temple Buell College in Denver in July of 1971. Fischer defeated the Danish grandmaster by the score of 6-0. While Taimanov was a respected grandmaster, Larsen was considered one of the very best players of the late 1960s and early 1970s. He played ahead of Fischer in the U.S.S.R. vs. the World match and dealt Bobby his only loss at the Palma de Mallorca Interzonal.

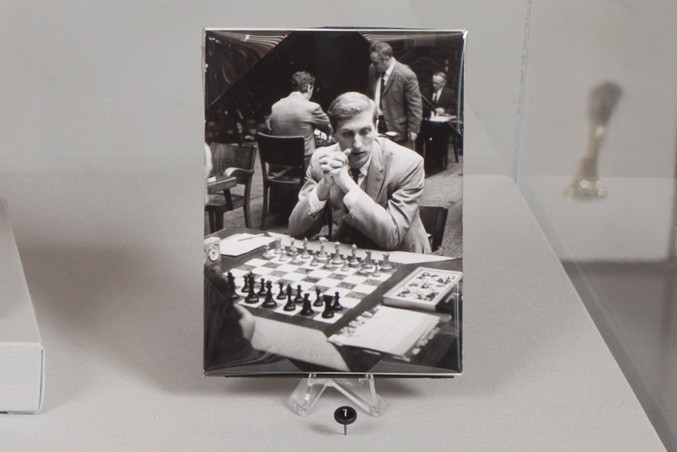

Dragoslav Andric

Bobby Fischer prepares for his game against Tigran Petrosian in the 1970 U.S.S.R. vs. the rest of the World Match

1970

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of John Donaldson

In this photo, a pensive Bobby Fischer prepares for his first round game against Tigran Petrosian in the U.S.S.R. vs. the World tournament. Immediately behind Bobby are Svetozar Gligoric and Yefim Geller (standing) with Samuel Reshevsky in the distance.

Portraits

Photographer unknown

Bobby Fischer, seen from above, analyzes during the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup

1966

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

In this view, Bobby Fischer analyzes game 22 of the Piatigorsky Cup, in which he faced German Grandmaster Wolfgang Unzicker. Their game would end in a draw. The Piatigorsky Cup, held in Santa Monica, California, in 1966, attracted some of the strongest players in the world, including a current World Champion, Tigran Petrosian, and two future ones, Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer. Spassky won the tournament, but after a disappointing performance mid-tournament, Fischer fought back to earn second place in the competition.

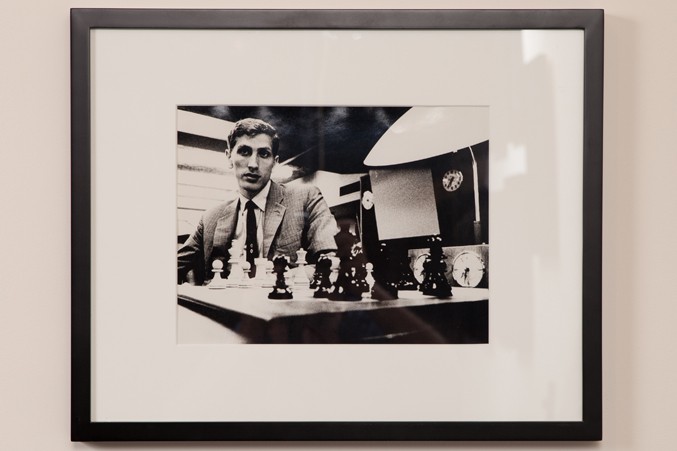

Photographer unknown

Bobby Fischer at the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup

1966

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

Fischer confidently gazes at the camera in this photograph captured at the second Piatigorsky Cup. Organized by the tournament’s namesake, Jacqueline Piatigorsky, the tournament proved that world-class events could be held in the United States. Fischer had faced professional setbacks in the mid-1960s, and his second-place win in the tournament renewed his confidence. He faced his future rival in the 1972 World Chess Championship twice in the tournament, losing the first game and drawing the second.

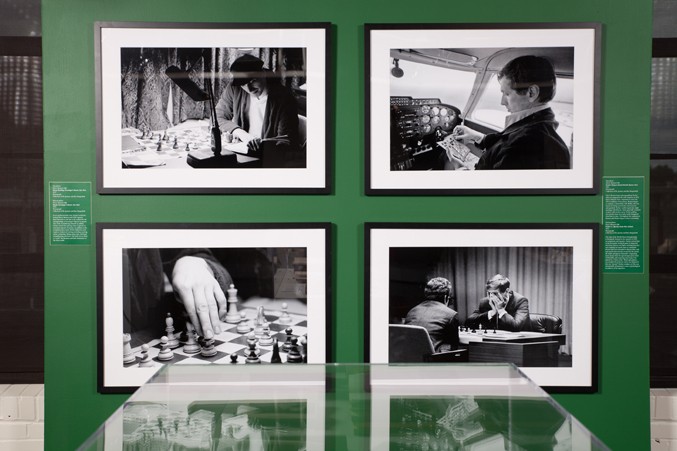

All photos by Harry Benson CBE

Top Left: Always Reading, Grossinger’s Resort, New York

1972

Photograph

Bottom Left: Hands, Grossinger’s Resort, New York

1972

Photograph

Top Right: Fischer Flying to Ranch Outside Buenos Aires

1971

Photograph

Bottom Right: Fischer vs. Spassky, Game One, Iceland

1972

Photograph

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

In an uncharacteristic twist, Fischer exclusively invited Harry Benson and LIFE reporter Brad Darrach to visit him as he trained for the championship at Grossinger’s Resort in upstate New York. Considering himself an athlete, Fischer noted that playing chess required an enormous amount of stamina. In addition to his scrupulous chess study, Fischer followed a strict regimen of physical training including running, tennis, swimming, biking, jump rope, and hand strengthening exercises—the latter in an effort to “crush” the Russians and their dominance of the chess world.

Harry Benson began photographing Fischer when on assignment for LIFE magazine in 1971. Sent to Buenos Aires, Argentina to cover the 1971 Candidates Tournament, Benson began to cultivate a relationship with Bobby, who was known for being notoriously camera-averse and guarded. Fischer would request late night meetings with Benson, which generally consisted of quiet walks broken up by Fischer pulling out a pocket chess set to play under lampposts from time to time. Throughout the assignment, Benson and Fischer began to form a friendship.

The tales of the World Chess Championship in Reykjavík, Iceland in the summer of 1972 are numerous and fantastic. Fischer arrived late to the first game, forfeited game 2, inspected television cameras and lights, insisting that they were making too much noise or contained devices that were intended to distract him, and had special chess boards created for the match. He made outrageous demands—requesting more money than the agreed-upon prize fund of $125,000, and requiring that Game 3 be played in a “back room.” Much speculation surrounded this behavior and it was debated if this was “normal” Fischer conduct, or if he was intentionally attempting to cause a psychological breakdown of his opponent.

Left: Harry Benson CBE

Fischer Portrait

1972

Photograph

Right: Harry Benson CBE

Bobby’s the Champ

1972

Photograph

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

Photographer Harry Benson continued to cultivate a journalistic friendship with Fischer while the two were in Iceland. They spent many hours together, walking and talking night after night through the hills of the Icelandic countryside. Benson noted that the pressure on Fischer was enormous—it is known that Fischer received several phone calls from Henry Kissinger encouraging him to play the match when he threatened not to. Noticing Fischer’s lack of social skills and recognizing his loneliness and isolation, Benson stated, “Bobby regarded the press as enemies, yet there had to be one friendly face in the enemy camp, and I figured it might as well be me.”

The World Chess Championship match was organized as the best of 24 games—wins would count as one point and draws as a half point, with the winner being the first to reach 12 ½ points. The first game took place on July 11th and the last game began on August 31st and was adjourned after 40 moves. Boris Spassky resigned the next day without resuming play and the 29-year-old Fischer won the match 12 ½ – 8 ½, becoming the 11th World Chess Champion and the first American-born player to do so—ending 24 years of Soviet domination of the World Chess Championship.

Audio Tour

International Master John Donaldson, a chess historian, interviews the participants in this audio tour. John has served as the Director of the Mechanics’ Institute Chess Club of San Francisco since 1998 and worked for Yasser Seirawan’s magazine, Inside Chess from 1988 to 2000. He has had held the title of International Master since 1983 and has two norms for the Grandmaster title, but is proudest of captaining the U.S. national team on 15 occasions winning two gold, three silver, and four bronze medals. Donaldson has authored over thirty books on the game including a two-volume work on Akiva Rubinstein with International Master Nikolay Minev.

All introductions to the passages are read by Dr. Leon Burke, Music Director and Conductor of the University City Symphony Orchestra and Assistant Conductor of the St. Louis Symphony Chorus.

A Memorable Life Introduction

Walter Browne

A six-time U.S. Champion, Walter Browne represented the United States in four Chess Olympiads, winning four team bronze medals. His biography and best games collection The Stress of Chess (and its infinite finesse) My Life, Career and 101 Best Games was published in 2012. Here, Browne recounts his experiences with Bobby Fischer.

Helgi Ólafsson

Grandmaster Helgi Olafsson has represented Iceland a record fifteen times in Chess Olympiads and won six national championships. He is also well-known for helping to bring Bobby Fischer to Iceland from Japan in 2005. He wrote about his experiences in Bobby Fischer Comes Home: The Final Years in Iceland, a Saga of Friendship and Lost Illusions. Here he speaks about his friendship with Fischer.

Viktors Pupols

Few American players have had longer chess careers than the Latvian-born National Master Viktors Pupols, who has been playing tournament chess for seven decades. A legend in the Pacific Northwest, Viktors is one of only three players to defeat Fischer on time. He is the subject of the book Viktors Pupols, American Master written by Larry Parr. Pupols speaks of his experiences competing against a young Bobby Fischer in the 1955 U.S. Junior Open.

Larry Remlinger

International Master Larry Remlinger was a great talent who grew up in Long Beach, California. A year older than Bobby Fischer, Larry finished second in the 1955 U.S. Junior Championship while Fischer placed in the middle. Soon thereafter, he gave up chess to focus on academics, but returned periodically to the game, obtaining his International Master title while in his 50s. Remlinger speaks of his experiences as a Junior player during the 1950s, the years in which he met Bobby Fischer.

Aben Rudy

Part 1

Part 2

Expert Aben Rudy was a good friend of Bobby Fischer when they were young. Ruby reported on Fischer’s meteoric rise to the top of the chess world during the mid-to-late 1950s in his column in Chess Life. Rudy also drew Bobby in two tournament games in 1956. Rudy reminisces about the New York chess scene, in which a young Bobby Fischer thrived.

Anthony Saidy

International Master Anthony Saidy is perhaps best known as the man responsible for ensuring Bobby Fischer arrived in Reykjavik, Iceland, in order to compete in the World Chess Championship. Saidy played United States Championship eight times and represented his country in the 1964 Chess Olympiad in Tel Aviv. He was also a member of the 1960 United States team that won the World Student Team Championship in Leningrad. His book The Battle of Chess Ideas has gone through several editions. Here, Saidy recalls his relationship with Fischer and his family.

Yasser Seirawan

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

One of the strongest American Grandmasters in the post-Bobby Fischer period, Yasser Seirawan was a twice a Candidate for the World Chess Championship. A four-time U.S. Champion, he has represented the United States in ten Chess Olympiads and one World Team Championship, winning four team and four individual medals. Seirawan is the author of over a dozen books on all aspects of the game including Five Crowns, an account of the 1990 World Championship match between Garry Kasparov and Anatoly Karpov. In this passage, Seirawan speaks of meeting Fischer during Fischer’s 1992 rematch with Boris Spassky.

James Sherwin

Part 1

Part 2

International Master James Sherwin very likely has the best record of any non-Grandmaster to ever compete in the U.S. Chess Championship. The highlight of his career was finishing third in the 1957 Chess Championship behind Bobby Fischer and Samuel Reshevsky. This qualified him to play in the 1958 Interzonal in Portoroz, Yugoslavia. Sherwin was the President of the American Chess Foundation during its golden period, offering strong support to top American players. Sherwin recalls his experiences with Fischer from the 1950s through the 1970s.

Walter Shipman

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

International Master Walter Shipman made his national debut at the 1946 United States Open in Pittsburgh and for the next decade was among the top fifteen players in the country. However, professional responsibilities and family kept him from being awarded the International Master title until 1982. One of the great gentlemen of American chess, Walter is best remembered for introducing Bobby Fischer to the Manhattan Chess Club in August 1955, and for being one of this country’s greatest chess historians. Here, Shipman describes his encounters with Bobby Fischer.

Lectures

4/9/2015: A Prodigy’s Progress—Lecture by IM John Donaldson (Video)

11/11/2014: A Conversation with GM Walter Browne (Video)

Press

A Memorable Life Exhibition Press Release

10/24/14: Mysteries at the Museum — Cold War Checkmate (Video)

9/30/14: The Chess Drum — Reflections of 2014 Sinquefield Cup

7/24/14: ArtDaily.org — ‘A Memorable Life: A Glimpse into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer’ opens at the World Chess Hall of Fame

7/23/14: St. Louis Public Radio — On Chess: Hall Of Fame Exhibit Peeks Inside The Complex Mind Of Bobby Fischer

7/17/14: USCF — A Memorable Life: Bobby Fischer Show at the World Chess Hall of Fame