Ladies’ Knight: A Female Perspective on Chess examines how a game often dominated by men inspires contemporary artists.

On View: October 29, 2015 – May 1, 2016

The exhibition presents works by Crystal Fischetti, Debbie Han, Barbara Kruger, Liliya Lifanova, Goshka Macuga, Sophie Matisse, Yoko Ono, Daniela Raytchev, Jennifer Shahade, Yuko Suga, Diana Thater, and Rachel Whiteread. Their diverse interpretations of the game range from the playful and feminine to the serious, and encourage dialogue about subjects like crime, language, peace and conflict, and inequality. The World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) endeavors to present exhibitions that honor the game’s pioneers, reflect its significant cultural impact, and appeal to a wide audience. In 2015 and 2016, the WCHOF is launching an initiative to encourage more women to take up the game. In February 2016, we will open another exhibition, Her Turn: Revolutionary Women of Chess, which will explore key historic moments in women’s chess history. Supporting these two exhibitions about women, the WCHOF will provide an array of programming for all ages and groups with chess classes and tournaments for girls and women, beginner’s classes taught by female chess stars, and lectures and entertaining evening programs with the help of its sister organization, the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis. Joining us in this initiative are two inspirational women who continue to make a huge impact on chess: two-time U.S. Women’s Chess Champion, poker player, and author Jennifer Shahade along with Executive Director of the United States Chess Federation Jean Hoffman. Together they formed 9 Queens, a nonprofit organization dedicated to empowerment through chess by making the game fun, exciting, and accessible—especially to underserved and underrepresented populations. Both Shahade and Hoffman contributed essays to this brochure and will be heavily involved in the programming for our exhibitions over the next year. Additionally, Shahade is a contributing artist in Ladies’ Knight.It is my hope that the artists in this exhibition and their interpretations of the game will inspire you to look at chess in a new way and encourage more girls and women to play!

—Chief Curator, Shannon BaileyThe Queen’s Gaze

by Chess Champion and Author, Jennifer Shahade

My passion for chess began with chess problems. Compositions, as they are also known, are created from scratch to highlight beautiful checkmates and ideas. They help make us stronger chess players, while never pretending toward educational purposes. Take this mate in two (pictured at right), by the well-known female composer, Edith Baird, who created hundreds of problems during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The creative act of composition was an end in itself for Baird. As she wrote in her book Seven Hundred Chess Problems Selected from the Compositions of Mrs. W.J. Baird (1902), “The fascination of composing has always been far greater to me than that of solving.”

In my book, Play Like A Girl: Tactics by 9 Queens (2011), I showcased checkmates and tricky tactics by top female champions to instill in young women that “playing like a girl” is a positive thing. Ladies’ Knight: A Female Perspective on Chess is the artistic version of that effort, highlighting the important voice of women in chess culture through its display of works that transcend gender and even chess.

The impact of women in chess goes beyond rankings and championships, and yet to overstate that runs the risk of reinforcing a pernicious back-handed compliment of which I have heard plenty of variations: women are too reasonable to play chess. Many of the pieces in Ladies’ Knight confront this dilemma head-on.

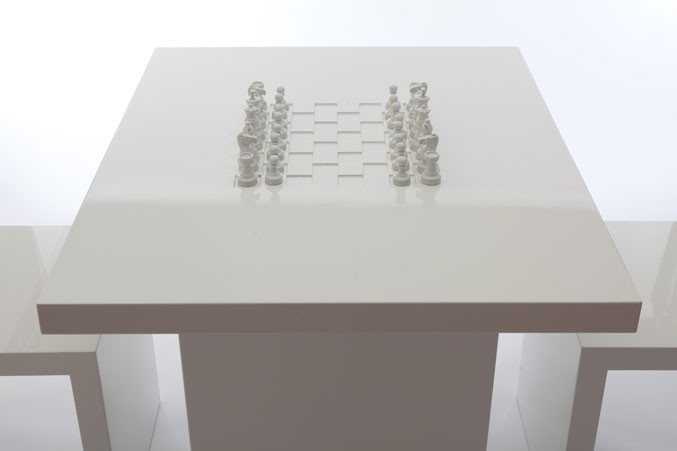

Rachel Whiteread’s Modern Chess set reminds me of the false dichotomy between domesticity and intellectualism. Much bloodshed over the chess board is done in privacy these days, in online games or in preparation for over-the-board games using databases. Brilliant moves that are prepared during the off season at a grandmaster’s laptop are referred to as “home-cooking.”

Yoko Ono’s Play it By Trust is the ultimate example of the tension between aesthetics and competition. It is a visually appealing takedown of chess as a war metaphor, but also a playable set that emphasizes skill even more than a two-toned set. A strong player will remember to whom each white piece belongs. While doing so she will be compelled to find a heightened focus, as in the popular exhibition format, “blindfold chess.” Proficient blindfold players can even play multiple games at once without looking at the board. Four-time U.S. Women’s Chess Champion Anna Zatonskih has given numerous blindfold simultaneous exhibitions in Saint Louis to promote events at the World Chess Hall of Fame and the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis.

I recently gave my first blindfold exhibition in Toronto in conjunction with the ChessBard, a program that converts chess games into poems. My brain had never felt so drained after just one hour. I also felt there was something very feminine about blindfold chess, in its theatrical and meditative nature.

One woman who I interviewed for my first book, Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport (2005) said that she was jealous of her boyfriend, who also played chess professionally, because he was more obsessive about the game than she was. This drive toward obsession in chess has always intrigued me. Some top players, such as World Chess Champion Magnus Carlsen, are models of a more balanced life that allows for sport and socializing as well as intense periods of chess training. Daniela Raytchev portrays various addictions in her set, from eating disorders to gambling. These potential poisons are depicted on pieces that can provide solace from addiction or become addictions in themselves.

In my performance piece Naked Chess (2009), Daniel Meirom and I flipped the iconic image of Marcel Duchamp playing chess against a naked woman, Eva Babitz. The pieces are nude sculptures, and I am playing against a tattooed young man. The viewer observes the scene through my eyes, watching the man as well as the nudes, flipping the male gaze in a way that surely would have pleased Duchamp’s female alter-ego, Rrose Sélavy.

Welcome to Ladies’ Knight, where women look at chess, rather than the other way around.

Women, Chess, and the Power of the Queen

by Executive Director of the United States Chess Federation, Jean Hoffman

Known by many as a game of war and kings, the chess world is often perceived as male-dominated. Today, less than 14% of the members of the United States Chess Federation (USCF) are female, and only one woman ranks in the top 100 chess players in the world. However—in spite of the underrepresentation of female players within today’s competitive chess world, women have played a central role in the development of the modern chess game. By examining how chess has inspired contemporary women artists, Ladies’ Knight: A Female Perspective on Chess provides a lens to explore the ways that women have contributed to chess in the past as well as their potential to change the game in the future.

Throughout history, women played a role in the development of one of the most celebrated symbols of feminine power on the chess board: the queen. Today, the queen is the most powerful piece on the board, faster and more dangerous than any of her male counterparts. But this was not always the case. When chess was originally developed in India around 600 CE, all the pieces were male. It was not until chess spread to Europe around 1000 CE that the figure of the chess queen began to appear on the chess board. At that time, the queen was one of the weakest pieces on the board, initially only able to move one square diagonally at a time.

By the end of the 15th century, the queen’s powers were transformed. In her book The Birth of the Chess Queen historian Marilyn Yalom shows how women played an integral role in the expansion of the queen’s powers. She posits that the reigns of strong female monarchs like Eleanor of Aquitaine, Catherine the Great, and Isabella of Castille led to the rise of the modern day chess queen as the most powerful piece on the board.

Despite the symbolic power of the chess queen today, female chess players are often treated as less powerful than their male counterparts. That is one of the reasons that in 2007, Jennifer Shahade and I founded the nonprofit organization 9 Queens. It is one of many organizations throughout the United States that has worked not only to increase the percentage of female chess players, but also to encourage women and girls to achieve academic, personal, and professional success.

Much more than a game, chess is a powerful educational tool with the potential to foster both creative and critical thinking skills. Chess is both a sport and art, and the benefits of the game can be enjoyed not only by players but also by spectators, students, and artists. Similarly everyone, regardless of gender or background, has the potential to experience the benefits of chess. I think of one of Barbara Kruger’s written statements in the show, “You are a piece of work,” not so much as one of fact but rather as a provocation— a provocation to challenge traditional power structures within a male-dominated world. Ladies’ Knight: A Female Perspective on Chess serves as an important reminder of the many ways women and girls can empower themselves through chess.

Crystal Fischetti

Crystal Fischetti is inspired by light, speed, and space. Her interest in literature, culture, physics, and philosophy is evident in her work, and she invites the audience to enter worlds of color which shape, move, and distort our perception of reality. Fischetti works on canvas, paper, and digital mediums. Her artwork is represented in private collections in London, New York, Los Angeles, Milan, Rome, Geneva, and Shanghai, as well as in the YueHu Museum in Shanghai.

In The Sun and Moon, Crystal Fischetti illustrates the concepts of courtship, love, and attraction through a game of chess. In this seductive version of the game, all moves are intelligent, calculated, elegant, slightly fearful, heated, cool, and overpoweringly sexy. A tragic and romantic story of the sun and moon Fischetti learned from her mother inspired the set. In the story, the Sun loved the Moon so much it would die at night to let the Moon breathe. Each day and night this would occur as they moved circularly and in symmetry until one rare occasion when they eclipsed each other. They were finally united, but only for a fleeting moment.

The masculine energy of the Sun is represented in the gold and yellow hues on one side of the chess pieces, while the feminine energy of the Moon is illustrated through the silver and blue hues. The meeting of the opposing pieces during a game symbolizes their sensual dance and spiritual union. The work is an interactive piece, and the unique physical appearance of the chess board at the end of each game describes the eclipse of her mother’s story in abstract form.Debbie Han

Debbie Han is a Korean-American artist who grew up in Los Angeles and received her Bachelor of Arts degree in Art from University of California, Los Angeles, and Master of Fine Arts degree from the Pratt Institute in New York. Han is deeply drawn to the issues of how human experiences are shaped and defined in contemporary culture. Her use of multi-layered staging of paradoxical dualities within the theme of idealized female imagery investigates subjects of race, culture, identity, and perception in today’s pluralistic societies.

The processes Han utilizes to create her work consist of a wide spectrum of methodologies that include appropriating classical images and craft techniques to cutting-edge photographic manipulation. Her various sculpture series executed in a wide range of materials and techniques possess both conceptual strength and visual power stemming from their laborious hands-on processes. Han’s works have been shown internationally, including fourteen solo exhibitions in the United States, Korea, China, Germany, and Spain. She also has participated in numerous group exhibitions in the United States, Asia, and Europe. Debbie Han lives and works in New York and Los Angeles.

In Battle of Conception, Han investigates the critical importance of perception as the key to defining oneself and the other. Here, the celebrated icon of beauty, Venus, becomes a signifier for social perception that shapes a social standard of beauty. One side has female figures with diverse racial and ethnic characteristics who oppose a group with obliterated facial features. The arbitrary mixing of diverse facial features on the iconic busts simultaneously demystifies the beauty myth as a social conception and renders racial hierarchy as volatile as a perception of beauty. At the same time, the playful but subversive hybridization of multi-racial features of these sculptures challenge the racial hierarchy within the global social dynamics. Han’s work shows that social conceptions and cultural experiences contribute critically to shaping one’s perception of reality.

Inspired by the organic beauty of Korean ceramics during an artist residency in South Korea, Han set out to execute this project in the ancient ceramic tradition of Korean celadon. This extraordinarily difficult technique took her seven years to complete.

Barbara Kruger

Barbara Kruger is an artist who has explored the juxtaposition of image and text since the late 1970s. Her bold works combining black-and-white photography and white-on-red type have become icons of late 20th-century art. With each successive exhibition, Kruger has demonstrated an embrace of new materials and technology while remaining faithful to her acute, often humorous, critique of popular society and culture.

In 1989, enlisting a process developed for billboards, she first showed large photo silkscreens on vinyl, occasionally utilizing color photography. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s Kruger was involved with numerous public art, editorial, and signage projects. In 1999, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles organized a mid-career retrospective that traveled to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. In June 2005, Barbara Kruger was awarded the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale, where she was also commissioned to design the façade of Italy’s national pavilion. This dual honor recognized the broad influence that her work has had on contemporary art, graphic design, and cultural discourse for nearly forty years.

Famous for her singular style that developed out of her background as a graphic designer and art director in the magazine publishing industry, Barbara Kruger uses the conventional interactivity of a chess match as a metaphor for the complex exchanges that take place during verbal communication. The basic concept of this chess set can be understood as a visualization of the theories of Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, particularly his use of the terms langue (language) and parole (speech) to distinguish between the impersonality of the written word and the individuality and subtlety of spoken language. When a piece is moved into a position, a microchip is triggered that randomly plays through a small speaker one of over one hundred possible statements, which are also printed on the set’s flight-case-style box in her signature Futura Bold Oblique typeface. With each match promising a unique exchange of phrases, the “conversation” mirrors not only the virtually limitless number of possible move sequences in a chess match, but also the vast number—and seemingly random interactions—of slogans, headlines, and sound bites seen and heard every day in the mass media.

Liliya Lifanova

Liliya Lifanova’s paintings, sculptural installations, and wearables for collaborative participatory videos and performances are positioned at the intersection of fine arts, experimental theater/performance, and film. Lifanova’s work is the struggle for abstraction as she broaches notions of identity within tradition, and the cultural memory of a political system destroying itself from within. Her work has been exhibited both nationally and internationally, most recently at Gridchinhall in Moscow, Russia, and the Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, New York. Lifanova received her Master of Fine Arts degree from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and has been awarded the Fulbright Fellowship for Installation Art. The artist lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

The title Anatomy is Destiny, a direct reference to the psycho-theory of Sigmund Freud, invokes the highly controversial theories that form the foundation of the psychosexual development of young boys and girls known as the Oedipus complex. This work consists of two components. The first is an installation of garments called The Wardrobe: Game in Waiting, which was exhibited at the World Chess Hall of Fame in 2011 and 2012. The second is the full-scale performance in which performers don the garments and execute the moves of an imaginary chess match between Marcel Duchamp and his infamous female alter ego, Rrose Sélavy, that was envisioned by the artist Arman in 1972.

Inspired by a diverse array of historical military fashions and constructed of linen backed with cotton, each garment in the wardrobe was designed by Lifanova to restrict the movement of the performer in such a way that approximates the respective movements of that piece on the game board. Two performances of Anatomy is Destiny are seen in the videos. One was presented at the Episcopal Church of the Epiphany in Chicago on September 11, 2009. The other was staged in conjunction with Out of the Box: Artists Play Chess, an inaugural exhibition at the World Chess Hall of Fame, and took place at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis on February 15, 2012.

Goshka Macuga

Born and raised in Warsaw, Poland, Goshka Macuga is an interdisciplinary artist who creates works that critically examine the histories of art, institutions, and politics. Her installation artworks, which are often large in scale, incorporate the work of famous artists, archival materials, other existing objects, as well as original pieces. Macuga’s work blends artistic and curatorial practices and encourages viewers to find new meanings and narratives in familiar objects.

Based in London, Macuga has exhibited extensively in the last several years at institutions and shows around the world, including the Venice, Liverpool, and Berlin Biennales; the Tate Modern; Walker Art Center; and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. In 2008, Macuga was nominated for the Turner Prize and is currently preparing for a solo exhibition at the New Museum.

The White-House made from Moscow evokes Cold War tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union through the lens of the chess board, a familiar metaphor for political maneuvers. In 1972, Bobby Fischer battled to win the World Chess Championship in a match against the Soviet player Boris Spassky, a sports contest that became emblematic of the struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union for cultural, political, and technological supremacy. Here, a model of the White House made of blocks is centered on a chess board and surrounded by wooden spikes, which resemble flames. Communism and its legacy inspired many of Macuga’s pieces—one of which includes artifacts related to the Soviet space program, another arena in which the two nations competed.

Sophie Matisse

With both art and chess in her blood, Sophie Matisse created and designed eight chess sets for the 2009 exhibition The Art of the Game, which was held in conjunction with San Diego’s Beyond the Border International Contemporary Art Fair. She felt her participation in this project was a living tribute to the presence of chess in her family. By adding color to the board, Matisse was exploring a different dimension to the game.

Before she was ten, Sophie Matisse learned to play chess from her father. During the many summers she spent with her grandmother Teeny in France, chess was a large part of their lives. She remembers a board that was imbedded into a table top with two time clocks on each side and pieces designed by Marcel Duchamp. She was never able to walk past the table without glancing down at the board. Though Matisse enjoyed playing the game, she often preferred drawing the pieces instead. Never quite sure which to call herself, une Problémiste or une Solutionniste, still today, she never travels without her 1972 edition of Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess, which she refers to as, “an old friend, tried and true.”

Yoko Ono

Yoko Ono is an artist whose thought-provoking work challenges people’s understanding of art and the world around them. From the beginning of her career, she has been a conceptualist whose work encompasses performance, instructions, film, music, and writing. Ono was born in Tokyo and moved to New York in 1953. By the late 1950s, she had become part of the city’s vibrant avant-garde activities. In 1960, she opened the Chambers Street loft to a series of radical performance work, and exhibited realizations of some of her early conceptual pieces there. In 1969, together with John Lennon, she realized Bed-In and the worldwide War Is Over! (if you want it) campaign for peace. Throughout the 1970s, 80s, 90s, and 2000s, Ono has continued to make films, records, and exhibited art work internationally. In 2009, she received the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement from the Venice Biennale. She continues to work for peace through her Imagine Peace campaign.

Starkly beautiful in its austere appearance and its unflinchingly straightforward concept, artist and longtime peace activist Yoko Ono’s all-white chess set Play It by Trust marries the spare, geometric lines of Minimalism with the intimate, playful interactivity of the games produced by the members of Fluxus, an international avant-garde movement with which Ono was associated in the 1960s. Originally conceived as the White Chess Set in 1966, Play It by Trust was born of a tumultuous era characterized by the Cold War tensions of the nuclear arms race, the military conflict in Vietnam, and the struggle for civil rights in the United States. As the players are forced into ever-greater reliance on each other to identify which piece belongs to which player as the game progresses, Ono elegantly recontextualizes a game that is normally thought of as a microcosmic allegory of war, emphasizing collaboration over competition and empathy over opposition.

Daniela Raytchev

Through her figurative and abstract drawings, Daniela Raytchev offers a rare subjective expression and her unique perceptions of the world. With a Foundation Diploma in Art and Design from Central Saint Martins and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the London College of Fashion, Raytchev creates artwork in a variety of media including sculpture, textiles, expressive paintings, and intricate drawings.

Raytchev shares her personal experiences and her impressions of her surroundings through her artwork. She explores conflicts, including social stigmas like addiction and abuse, and attempts to illustrate their emotional, psychological, and physical effects. Her work serves as a visual interpretation of the impact of these often internal struggles.

In Addictions, Daniela Raytchev portrays common and sad inner battles through the martial imagery of chess. Here, the black pieces represent the negative destructive self, supported by the toxic crutches one may hold onto as a result of fear and anxiety. They battle against the white pieces representing the loving, positive, and nurturing self.

The black queen, bishops, knights, and rooks illustrate a range of addictions, including alcohol, drugs, food, shopping, and relationships, among others. Spiked pawns guard the back rank, creating an uncomfortable barrier and blocking the pieces from the other “world.” The white kings, queen, bishops, knights, and rooks are decorated with delicate paintings of the natural world as well as other symbols of beauty and joy. These seemingly simple experiences can improve lives, making them happier and richer when one is not burdened by negativity. The set serves as a reminder that only when one is not ensnared in the destructive clutches of addictions can one have a clear enough mind to be able to enjoy such simple pleasures.

Both kings are the same—white—a metaphor to express that people are primarily good, but addiction is just an illness that one may suffer. One is fighting against oneself, thus no one really wins.

Diana Thater

Born in San Francisco, Thater studied Art History at New York University, before receiving her Master of Fine Arts degree from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California. Since 1993, the artist’s work has been represented by David Zwirner Gallery. Opening November 22, 2015, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art will host a comprehensive mid-career survey of Thater’s work, The Sympathetic Imagination, which will travel to the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago in 2016. Also a prolific writer, educator, and curator, Thater lives and works in Los Angeles.

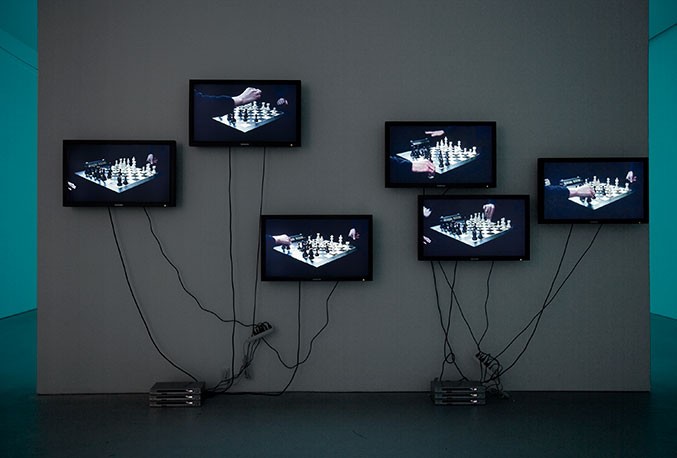

Depicting black-and-white boards and games played by disembodied hands, Diana Thater presents a mixture of scripted and impromptu chess matches, simultaneously investigating ideas of history, rationality, reproduction, and time. Depending on a viewer’s familiarity with the rules of the game, the works may operate as intricate narratives or conversely as abstract series of images. This allows for layered interpretations and diverse modes of viewing, and emblematizes Thater’s stated belief that film and video are not by definition narrative media, and that abstraction can, and does, exist in representational moving images.

In memoriam of Bobby Fischer, who died on January 17, 2008, Thater created three monitor pieces, representing major moments in Fischer’s life. Thater presents Fischer’s stunning triumph at age thirteen over Donald Byrne, his spectacular victory over Russian World Chess Champion Boris Spassky in 1972, and the daring reprise match against Spassky twenty years later in Yugoslavia. Shot sequentially throughout the day—at morning, midday, and dusk—the works capture varying light intensities, thus aesthetically and metaphorically dramatizing the trajectory of Fischer’s legendary career. The six-monitor Blitz shows players competing in three-minute games. In contrast to the other chess pieces in the exhibition, the games for this work are completely unscripted, as Thater presents members of the Los Angeles Chess Club playing six blitz games in real time.

Jennifer Shahade

Jennifer Shahade is a chess champion, author, commentator, and poker player. She is a two-time American Women’s Chess Champion and the editor at U.S. Chess. Her first book, Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport (2005), intertwined autobiographical elements with the stories of great women chess champions, past and present. Shahade also co-authored Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Chess (2009). Jennifer’s Play Like a Girl! Tactics by 9 Queens (2010) is the first book featuring solely combinations that are all executed by female chess champions.

Shahade created the performance pieces Hulachess (2009) and Naked Chess (2009) with Daniel Meirom and Roulette Chess (2010) with artist and curator Larry List. Hulachess was selected for the first online gallery of the YouTube Play Biennial organized by the Guggenheim. In 2007, Shahade and Jean Hoffman founded 9 Queens, a non-profit organization that provides chess instruction to those most in need of its benefits, especially girls and at-risk youth. All the author royalties of her latest book, Play Like a Girl! Tactics by 9 Queens, benefit 9 Queens initiatives. Jennifer is the MindSports Ambassador for PokerStars and a commentator for the Grand Chess Tour and the U.S. Chess Championships.

With Daniel Meirom, Shahade created Naked Chess, which is inspired by the famous Julian Wasser photograph of the artist and chess player Marcel Duchamp playing chess against the artist and author Eve Babitz. Staged at Duchamp’s retrospective at the Pasadena Museum of Art in 1963, the 20 year-old naked Babitz sits across from the 76-year old artist, who is fully-clothed and surrounded by his art.

To update this scene, Shahade features herself as the clothed and dominant chess player in a game against a naked man, Jason Bretz. The two use pieces that are nude figurines. Shahade chose to base the game played on a Duchamp win over E.H. Smith—one of the 15 games she analyzed in the book Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Chess. Contrary to the events in this video, Smith did not play all the way to checkmate in the original game—he resigned a couple moves before ending in a totally lost position.

Yuko Suga

Rachel Whiteread