The Staunton Standard includes a spectacular array of Staunton and Staunton-style chessmen, which were first introduced to the public in September of 1849 and are still the international standard for tournament play. The exhibit showcases early Staunton chessmen as well as sets owned by famous players and those created for historic tournaments.

On view: April 12 – September 16, 2018

Photography by Michael DeFilippo

Artifacts: Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the House of Staunton; Collection of Jon Crumiller; Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield; Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame; Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Hartwig Inc.; Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame; Collection of Jon Crumiller

The Staunton Standard: Evolution of the Modern Chess Set

2018 marks the tenth anniversary of the Saint Louis Chess Club (STLCC), which now hosts some of the United States’ and the world’s most prestigious chess tournaments, making it the perfect time to examine the history of the Staunton chessmen. Their familiar pieces are used in these competitions as well as elite tournaments around the world. The Staunton chessmen, first introduced to the public in 1849, are now so well-known that their form is taken for granted. However, they only rose to prominence through the efforts of their namesake, 2016 World Chess Hall of Fame inductee Howard Staunton (1810-1874). Staunton, a top player of the 1840s as well as a writer and promoter of chess, was an early proponent of the set during a time when multiple styles of sets proliferated throughout Europe and around the world. Its advantages were clear, as stated by Staunton himself in a June 2, 1850, issue of the Illustrated London News. “In the simplicity and elegance of their form, combining apparent lightness with real solidity, in the nicety of their proportions one with another, so that in the most intricate positions every piece stands out distinctively, neither hidden nor overshadowed by its fellows, the ‘Staunton Chess-men’ are incomparably superior to any others we have ever seen.”

First produced by Jaques of London, competing firms quickly imitated the pattern. Jaques produced ads warning, “Caution—As spurious imitations are sometimes offered, purchasers are requested to observe Mr. Staunton’s signature on the box, without which none are genuine.” By 1863, publications from locations as far-flung as Australia’s Sydney Morning Herald declared a local auction house would be selling “Solid ivory Staunton chessmen, as used in the Paris and London clubs.” The New York Times published an 1853 ad for Bangs, Brother & Co. advertising “Several elegant sets of the STAUNTON CHESSMEN with the Carton Pierre Box,” and in 1873, the Helena Weekly Herald declared that players in Bozeman and Deer Lodge, Montana, would compete in a telegraph match with Staunton chessmen of English manufacture as the prize. Additionally, U.S. and World Chess Hall of Fame inductee Paul Morphy (1837-1884) challenged Staunton to a match in 1858 to be played, “with Staunton chessmen of the usual club-size, and on a board of corresponding dimensions.” During his 1858 visit to Europe, Morphy also challenged “Alter,” a strong well-known amateur player to a match with a set of ivory club-size Staunton chessmen as a prize for the winner of the first five games. Though Jaques warned of imitators, the pattern’s popularity could not be denied, and by the late 19th century, the set was mass-produced by multiple companies.

The 20th century saw a number of innovations for the set, from its aforementioned mass-production in a number of materials from wood to Bakelite, catalin, lead, and plastic, to the 1998 introduction of Digital Game Technology (DGT) boards and pieces. DGT boards, which record the moves of the pieces, allowed chess fans to follow games as they happen rather than waiting until they were published in chess periodicals. The Staunton Standard: Evolution of the Modern Chess Set contains examples of Staunton and Staunton-style chess sets from the 1840s through the present-day, showing how the set has both become a tradition as well as how creators have customized it to make it their own.

The show includes spectacular sets from the collection of Jon Crumiller, who owns some of the earliest Staunton Chessmen created. Crumiller has worked with the World Chess Hall of Fame on two previous exhibitions: Prized and Played: Highlights from the Jon Crumiller Collection (May 3 – September 15, 2013) and Encore! Ivory Chess Treasures from the Jon Crumiller Collection (May 14 – October 18, 2015), lending both sets from his collection and his knowledge of antique sets and their makers. His collection contains over 600 sets from more than 40 countries, with the earliest set dating from the 11th century.

Shannon Bailey, Chief Curator, World Chess Hall of Fame

Emily Allred, Associate Curator, World Chess Hall of Fame

The Staunton Chessmen: Rook of Ages

Chess games are often won by the heroics of a single well-placed piece on the board: proverbially, the right chessman in the right place at the right time. In a larger context, the English chess champion Howard Staunton was precisely the right man to introduce and endorse a new universal design for chess pieces. And in the right place, at the right time: Victorian London was a locus of the world’s chess activity, as chronicled by Staunton in his weekly chess column in the Illustrated London News (ILN).

Howard Staunton never claimed to be the designer/creator of the chess piece pattern that bears his name. The Staunton chess pattern was patented in March 1849 by Nathaniel Cooke (misspelled as “Cook” on the patent document). Cooke was the business partner and brother-in-law of Herbert Ingram, the primary founder of the ILN. Although the Staunton design is officially attributed to Cooke, speculation abounds as to other possible contributors—perhaps John Jaques, the manufacturer of the first Staunton chess sets; or perhaps Staunton himself influenced the design in some way.

Regardless of the set’s actual designer, the direct connection of Staunton’s name with the new design was a savvy and effective marketing tactic. Celebrity branding is common these days—Air Jordan sneakers and the George Foreman grill come to mind—but all of today’s named products share a marketing ancestor: Howard Staunton was one of the earliest celebrities in modern history to lend his name to a product. And Staunton’s name carried considerable weight within the chess audience of his far-reaching weekly ILN column. And indeed, he advertised the Staunton pattern relentlessly in his column. The first mention comes in the September 8, 1849, ILN issue:

“The Staunton Chess-men.” — We have lately been favoured with a sight of the newly-designed Chess-men you speak of, and shall be greatly mistaken if, in a very short time, these beautiful pieces do not entirely supersede the ungainly, inexpressive ones we have been hitherto contented with. In the simplicity and elegance of their form, combining apparent lightness with real solidity, in the nicety of their proportions one with another, so that in the most intricate positions every piece stands out distinctively, neither hidden nor overshadowed by its fellows, the “Staunton Chess-men” are incomparably superior to any others we have ever seen.

Photo by Michael DeFilippo

Staunton repeated these accolades, and others, in column after column. All 16 subsequent columns in 1849 touted the benefits of the Staunton pattern, as did the vast majority of columns in 1850, and onward, spanning over a 20-year period. And Staunton’s efforts were gradually rewarded, not due solely to his diligence, but also due to one important fact: he was right! For the actual playing of chess games, the Staunton pattern is indeed “superior to any other” with “simplicity and elegance of their form, combining apparent lightness with real solidity.” Especially when compared to the prevalent chess patterns of the era, e.g. the Old English pieces, with short pawns often hidden behind other pieces; or the Barleycorn and Edinburgh patterns, easily tipped over; or the ornamental patterns, fragile and breakable; or, in France, the Directoire and Régence patterns that could be knocked askance with the slightest errant touch.

It took quite a while for the new design to become popular. Initial sales were slow, in spite of Staunton’s frequent assertions to the contrary in his weekly column. A portrait of Howard Staunton posing with other leading chess players in the July 14, 1855, issue of the Illustrated London News includes a Barleycorn set, not a Staunton set, on the table! But slowly, surely, the advantages of the Staunton standard won out over all others, and by the end of the 19th century it had become the prevalent chess set pattern. Other patterns were still marketed in chess manufacturers’ catalogs, even well into the 20th century, but the dominance of Staunton’s standard continued to increase until it became the only chess set design allowed in major chess tournaments, starting in the 1920s.

Howard Staunton’s preeminent place in history would have been assured solely on his exploits as the world’s top player in the 1840s. Or solely on the chess literature he produced: 1,440 weekly ILN chess columns, a dozen chess books, several magazines, and hundreds of articles. Or on his relentless efforts to popularize the game. Or even on his other endeavors, as a Shakespearean scholar (he wrote a 3-volume, 2,400-page book series on Shakespeare’s plays) or as an authority on education (he authored The Great Schools of England, a treatise on educational reform). But first and foremost, Staunton’s legacy is inevitably linked to the chess set pattern, “superior to any other,” that bears his name: the Staunton standard.

—Jon Crumiller

A longtime chess fan and competitor, Jon Crumiller purchased his first antique chess set online in 2002. This acquisition quickly sparked a passion, and Jon’s collection of antique sets now numbers over 600. It includes pieces originating from over 40 countries, dating back to the 11th century (and gaming pieces dating to 3000 BCE), unique sets owned by 18th- and 19th-century royalty, and made from materials such as jade, silver and gold, bone, wood, and precious stones, among others.

The scope of his collecting has also grown to include chess boards, timers, and chess miscellanea, mainly from the 19th and 20th centuries. Now recognized as one of the greatest chess set collections in the world, the artifacts he has gathered serve as a visual history of the diverse ways that cultures across time and around the world have interpreted the game of kings. Portions of Crumiller’s collections have been highlighted in two previous WCHOF exhibitions. Not only interested in acquiring artifacts but also learning about their origins and histories, Jon conducts research on the evolution of chess set styles, usage, and manufacturing. He shares this information with the global community of collectors, including his fellow enthusiasts in Chess Collectors International. Jon provides curious chess devotees from around the world with beautiful photos of his stunning collection as well as some of the fruits of his meticulous research through his website www.chessantique.com.

On Collecting Staunton Chessmen

My chess set collecting obsession had its start a few months after I first learned the moves of the game. That was the summer before my 16th birthday. A few friends in my new neighborhood took the pains to explain the moves to me and I was addicted. All I could do was eat, drink, and sleep chess. I was entering my junior year in high school. I turned 16 in the fall of that year and, for my birthday, my mother gave me a nice set of wooden Staunton chessmen. These were nothing spectacular, just a good, solid, German-made weighted set of lacquered chessmen in a wood slide-top box. The pieces were tournament size, and I made good use of them in the years that followed.

First, having been a serious tournament chess player, my interest was in practical playing sets—the Staunton design in particular. What I had discovered very early in my collecting career was that there was woefully little information on the Staunton chessmen and what did exist was mostly incorrect. So, I decided to pull together as much information on the Staunton pattern as I could.

The Staunton chessmen were designed and first manufactured in the United Kingdom by the firm of John Jaques. I obtained a copy of the design registration for the Staunton chessmen from the patent office in London. The Staunton chessmen design was registered as number 58607 on March 1, 1849. The title of the registration was “Ornamental Design for a set of Chess-Men.” It was registered by Nathaniel Cooke, 198, Strand, London, under the Ornamental Designs Act of 1842. Interestingly, the registration was limited to Class II, articles fabricated mostly from wood.

The Chessmen:

The original Staunton chessmen produced by John Jaques were and still are quite unique in appearance. Although generally described as a radically new design for their time, the form was based on the earlier Edinburgh Upright Chessmen which were designed in the 1840s by Lord John Hay. The Staunton chessmen featured very broad bases, gracefully contoured stems and attractively turned and carved headpieces. From the graceful Formeé cross atop the king to the six-crenelled rook, these chessmen make an impression. The knights, however, are their hallmark. They were derived from the visages which adorn the Elgin Marbles, which form a part of the east Pediment of the Greek Acropolis. The “Marbles” were “expropriated” in 1816 by Sir Thomas Bruce and brought to London. They can be viewed today at The British Museum in London.

The original Staunton Chessmen were available in a Standard size (8.9 cm king) and a Full Club size (11 cm king) only. The original chessmen were available in boxwood and ebony, ivory and Wedgwood Carrara(!). This latter is largely unknown to both the Wedgwood and the chess collector communities. Jaques originated the praxis of weighting their chessmen for enhanced stability. In a true Jaques set, the king’s crosses are removable. Also, the knights are two pieces—the head and the base-which are screwed together. Jaques was the first chess set manufacturer to affix the symbol of a king’s crown to the summits of the kingside rooks and knights. This praxis was largely copied and is not unique to sets produced by Jaques. Every Jaques chess set will have “Jaques London” imprinted on the upper part of the rim of the base of the white king if the set is boxwood and ebony and on the underside of the base of the ivory king. Both kings are so marked for sets produced after around 1890.

Registration Certificates:

Each chessman in a Jaques set, sold during the first three years of production, had a small green paper disk affixed to the underside of their bases. This disk bore a registration mark consisting of a small diamond which identified the day, month and year the design was registered, the class, and a parcel number. This protected the design from piracy during those three years. Although the pamphlet from the patent office in the UK lists one registration disk design for 1849, the year the Staunton chessmen were registered, I have discovered that there were actually three designs printed and distributed. The first two had printing errors and omissions. These were used from 1849 to 1852.

Boxes and Carton-Pierre Caskets:

Perhaps the most intriguing aspects of collecting Jaques Staunton are the richly adorned Gothic style Carton-Pierre caskets in which they were housed. These caskets were designed by Joseph L. Williams. Matching Carton-Pierre treatment adorned leather chess boards were designed and sold by William Leuchars and first offered to the public in December, 1849. Chessmen were initially housed in hinge-top mahogany boxes with a semi-mortise lock and key, Carton-Pierre caskets in three configurations for “unweighted” wooden and ivory chessmen, and the large Spanish mahogany coffer with removable compartmented trays for the club-size ivory chessmen.

The mahogany boxes which housed the earliest boxwood and ebony chessmen were distinctive. They had unique handmade dovetail joints, soft, slightly rounded corners, and they bore their manufacturers label on their undersides. Some of the earliest boxes also bore a small green label on the underside of the lid. Printed on that small label were the words “The Staunton Chessmen Jaques, London.” This label is quite rare and a good indication that the box is one of the earliest made to house the Staunton chessmen. Later mahogany boxes would carry their labels on the underside of the lid. This did help preserve the labels since they were not placed directly on a wear surface.

Photo by Michael DeFilippo

Early Labels (1849-1851):

Each box bore a manufacturer’s label affixed to the underside of the box or on the bottom inside of the large Spanish mahogany caskets. This praxis was later changed to affix the label to the underside of the lid of the mahogany boxes. The earliest labels were white with a decorative black fleur-de-lis. A slightly different label was designed for sets numbered 600 or so to 999.

Along with the box contents and registration number (58,607 5&6 Vict. Cap. 100.), each label bore an original (not a facsimile) signature of Howard Staunton and the production number of the set, also in Staunton’s hand. Based on certain observations, I believe Staunton hand-signed and numbered 999 labels (or signed as many as he could until hampered by writer’s cramp).

These early labels were numbered sequentially, so set #120 could be an 8.9 cm wooden set in a small mahogany box, while set #121 might be a large ivory set in a large Carton Pierre casket. Little known is the fact that the earliest labels also have the Jaques London imprint invisibly embossed into the label. The same tool used to mark the bases of their kings was used to make this imprint. This little-known fact alone should be worth the time you have taken to read this article. These labels were used for sets sold during the first two years of production.

Numbered Labels (1852-1856):

After three years, the design registration expired and was not renewable. On August 11, 1852, Nathaniel Cooke entered into an arrangement with Howard Staunton for the exclusive use of his name and facsimile signature on the labels. This next group of labels was produced under this new arrangement. Labels within each of the three color groups were numbered sequentially without regard for the size of the chessmen.

The Leuchars Factor:

The earliest advertisements for the new Staunton chessmen have the following statement: “The Nobility and Gentry are respectfully informed that these new and elegant CHESS-MEN are now obtainable of W. Leuchars, 28. PICADILLY …” The earliest Jaques chessmen were sold through Leuchars and are quite valuable and have unique features. The Jaques London mark on the bases of both the wooden and the Ivory sets were over-stamped “Leuchars.” In the case of the ivory sets, the Jaques London mark is actually scratched out and over stamped. In addition, a Leuchars green sticker was affixed to the underside of the white king’s base. Leuchars ivory sets were sold only in Carton-Pierre caskets and only in the 8.9 cm king. The label on the bottom of the casket originally bore a green Leuchars sticker. Leuchars ivory sets also featured a very unique knight design which was clearly distinguishable from the more normal Jaques knight. Leuchars only offered boxwood and ebony sets in the 8.9” king. Unlike Jaques, Leuchars also offered lead-weighting in the smaller boxwood and ebony sets sold between 1849 and 1852. Although somewhat difficult to see, the Jaques London mark on the upper bevel of the king’s base is over-stamped Leuchars.

The Design Evolves:

The Jaques Staunton chessmen have evolved over the 150 or so years since their introduction. Many of the changes were made to improve the robustness of the chessmen. Among the other changes made were the relative proportions of the chessmen. Queens and pawns were made taller. The weight of the chessmen was increased. Boxes and labels also underwent significant changes. Boxes housing sets produced after 1895 or so were fitted with a partition which separated the white pieces from the black. Labels changed every five years or so.

—Frank Camaratta

The full version of this article first appeared in the November 2008 issue of Chess Life.

Frank Camaratta is the internationally-recognized expert in antique Staunton and other playing sets. Between 1986 and 2010, he owned one of the world’s largest collections of Jaques and Staunton-style sets, which numbered well over 1,000 sets. He has been a serious collector and researcher into antique playing chess sets, their design and history since 1986. His serious research, which started in 1989, was centered on Jaques and other Staunton chessmen and quickly expanded into Pre-Staunton playing sets. Camaratta is a serious chess tournament player, national title holder, International Correspondence Chess Master, collector, and historian with a broad educational and professional background. He purchases and sells chess collections, large and small, and has provided numerous appraisal and research services. In addition, Camaratta has brokered the sale of several large collections in the States and overseas. In 1990, Camaratta founded The House of Staunton, Inc. and later, The House of Staunton Antiques, LLC. His website is chessantiques.com.

United States

Sinquefield Cup Imperial Chessmen

2018

King size: 8 in.

Board: ⅞ x 34 x 34 in.

Boxwood, maple, and zebrawood

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Frank A. Camaratta

This exquisite set is a supersized version of the set that Frank Camaratta created for the 2013 Sinquefield Cup, a tournament held annually at the Saint Louis Chess Club that includes the greatest players in the United States and the world. The king in this set is over double the height of the one in the Sinquefield Cup set, which is also on view in this gallery. The Sinquefield Cup set itself is a smaller version of the Imperial Collector set. This oversized set is one of only two that exist—the other is a gift from Camaratta to Rex Sinquefield, the founder of the Saint Louis Chess Club and the World Chess Hall of Fame.

England

English Ivory Playing Set

1840

King size: 4 ⅞ in.

Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

England

Victorian Tilt-top Chess Table

1850

28 x 22 x 22 in.

Papier mâché and wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

England

Calvert Stamped Ivory Set

1820

King size: 2 ⅝ in.

Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

England

Victorian Gothic Penwork Chess Table

Late 1800s

29 x 17 x 17 in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Two of the popular styles of English playing sets that were displaced by the Staunton style are displayed here on a pair of beautiful Victorian chess tables. John Calvert created the Calvert Stamped set. After his 1822 death, his wife Dorothy Calvert then took over and kept his company running. She then sold the stock in 1835 and later died in 1840. The set is displayed on a table with elaborate penwork imitating the appearance of a “specimen table” or a tabletop inset with different varieties of marble.

An elegant English ivory chess set is paired with the tilt-top table. The set includes elements both typical of pre-Staunton playing sets, such as stacked “collar” decorations on the pieces, as well as ornamental elements like the waving rook flags.

England

Jaques 1849 Club Size Wooden Set

1849

King size: 4 ½ in.

Box: 4 ⅝ x 6 ¾ x 8 ¾ in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

England

English Mahogany Chess Table

Early 1900s

34 x 20 x 30 in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Advertisements indicated that early Staunton chessmen, like the ones on view here, were available in boxwood and ebony, ivory, and Wedgwood Carrara. Though made from wood and ivory, which were conventional materials for playing sets during that era, Staunton chessmen included a number of innovations, even aside from their forms. Jaques originated the praxis of weighting their chessmen for enhanced stability. Additionally, Jaques was the first chess set manufacturer to affix the symbol of a king’s crown to the summits of the kingside rooks and knights. Howard Staunton himself indicated that this would aid players in their study and analysis of games.

Cuba

Havana 1966 Olympiad Set

1966

King size: 3 13/16 in.

Box size: 4 11/16 x 12 x 19 5/16 in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Cuba

Chess Table from the 1966 Havana, Cuba, Chess Olympiad

1966

Chairs: 33 x 22 x 18 in.

Table: 30 x 45 x 36 in.

Board: 7/8 x 19 ½ x 19 ½ in.

Wood, leather, fabric, and marble

Collection of the U.S. Chess Trust

This mid-century modern set of table and chairs as well as the chess set displayed on it were created for the 1966 Havana, Cuba, Chess Olympiad. Chess Olympiads are biannual chess competitions featuring teams of players representing countries around the world. The Havana organizers made special efforts to make it one of the best Olympiads in history. In a December 1966 article in Chess Life, U.S. team member Larry Evans noted that it was the “biggest, best organized, and best run to date” and that organizers reportedly spent 1.3 million pesos on the event. After the event was over, the organizers sent tables and chess sets to Board One players and important FIDE (Fédération Internationale des Échecs or World Chess Federation) officials around the world. Fred Cramer, then Zonal President for the United States, received the table on display, while International Master Nevzat Süer, who played Board One for Turkey, received the set. The table has replica flags and name placards. Since the tables were used continuously throughout the tournament, it is impossible to tell which players competed at specific tables; however, no matter who played on this table, it is an important part of chess history.

One key to the enduring influence and popularity of the Staunton chessmen may be the classical forms that Nathaniel Cooke sought out when creating them. The knights are modeled after the sculpture of the horse pulling the chariot of the Greek goddess of the moon, Selene, that appeared in a scene on the east pediment of the Parthenon, a temple dedicated to the goddess Athena. The sculpture is part of the Elgin Marbles, a group of sculptures from the Parthenon that were brought to Great Britain by Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, from 1801 to 1812. The other Staunton-designed pieces also had symbolic significance: the king was topped by a formée cross, a reference to that on the British Imperial crown, and, like the headgear of high-ranking church officials, the top of the bishop resembled a flame, a reference to the Holy Spirit in Christian theology.

England

Jaques #9

1849

King size: 4 1⁄2 in.

Box: 5 5⁄8 x 9 x 6 7⁄8 in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

England

Jaques Stamped Board

1900

1 x 22 x 22 in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

England

Jaques Congress Timer

1895

9 1⁄2 x 2 1⁄2 x 7 in.

Wood and metal

Collection of Jon Crumiller

One of the oldest sets of Staunton chessmen, this set is accompanied by a box with a label hand-signed and hand-numbered (#9) by Howard Staunton himself. Staunton, one of the top players of the 1840s, endorsed the set in his column in the Illustrated London News and signed several hundred labels for the early sets. He noted the importance of looking for the signature’s presence in order to avoid a forgery of the new pattern.

In the October 13, 1849, edition of his column, Staunton stated, “The new REGISTERED Chess-men are sold in a box, each box having a label at the bottom outside, with the price of the set and the signature ‘H. Staunton’ on it; and the public are particularly cautioned not to purchase any sets of Chess-men which may be offered as the new pattern, without seeing that the above label is attached.” As the producer of the famous Staunton chess set, Jaques of London was a leading chess manufacturer beginning in the nineteenth century. While in earlier centuries, chess games had no time limit, by the 1880s, time controls were widespread. To accommodate this new development, Jaques and other game equipment firms began to market the two-faced chess clock.

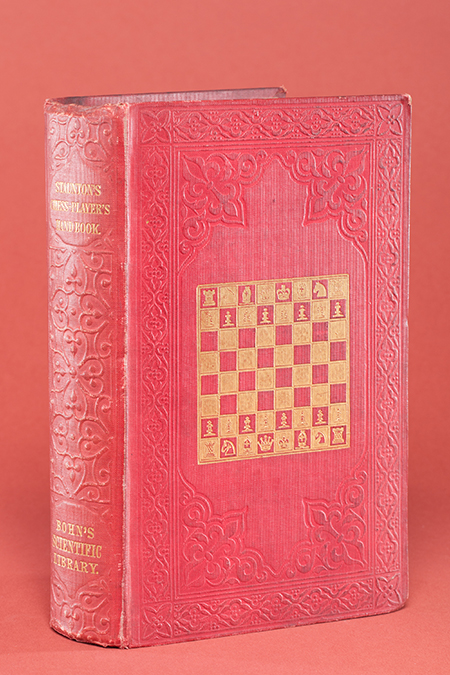

Howard Staunton

The Chess Player’s Handbook

1848

1 1⁄2 x 7 1⁄4 x 5 in.

Book

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Howard Staunton

Chess Praxis: A Supplement to the Chess Player’s Handbook Owned by Paul Morphy

1860

1 3/16 x 5 1⁄8 x 7 3⁄8 in.

Book

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Howard Staunton

Chess Praxis: A Supplement to the Chess Player’s Handbook Owned and Signed by Bobby Fischer

1860

1 5⁄8 x 7 x 5 in.

Book

Collection of Jon Crumiller

In addition to being one of the greatest players of his era, Howard Staunton was also an author of chess literature and a Shakespearean scholar. On view in this exhibition are two copies of his 1849 book Chess Praxis, which were once owned by two of the United States—and world’s—best players, Paul Morphy and Bobby Fischer. Alongside them is a copy of The Chess Player’s Handbook, which Staunton noted would be included with the Staunton chessmen along with the carton-pierre casket in his Illustrated London News column.

England

Jaques 50th Set given by Lord Vernon

1855

King size: 4 1⁄2 in.

Box: 5 1⁄8 x 8 3⁄8 x 6 in. Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

This trophy or gift set is named for the man who presented it, a member of the British Parliament named Lord Vernon. An inscription on the base of the box that accompanies this set indicated that he presented it as a gift at his residence, Sudbury Hall, in October 1857. The set is accompanied by a beautiful carton-pierre casket (box), intended both for the utilitarian purposes of storing pieces and display as a piece of art.

Howard Staunton sought to establish his namesake sets as luxury items, and the sets on view in this case bear witness to his success. The Carton-Pierre (papier-maché) case for the Jaques 50th set has elaborate Gothic arches with figures representing each of the pieces, while the Jaques “Tees Side Trophy” Set was prized by an association of chess clubs in northern England as a prize for 117 years. Contemporary accounts also speak to his success. By 1863, publications from locations as far-flung as Australia’s Sydney Morning Herald declared a local auction house would be selling “Solid ivory Staunton chessmen, as used in the Paris and London clubs.”

The New York Times published an 1853 ad for Bangs, Brother & Co. advertising “Several elegant sets of the STAUNTON CHESSMEN with the Carton Pierre Box,” and in 1873, the Helena Weekly Herald declared that players in Bozeman and Deer Lodge, Montana, would compete in a telegraph match with Staunton chessmen of English manufacture as the prize. Additionally, U.S. and World Chess Hall of Fame inductee Paul Morphy (1837-1884) challenged Staunton to a match in 1858 to be played, “with Staunton chessmen of the usual club-size, and on a board of corresponding dimensions.” During his 1858 visit to Europe, Morphy also challenged “Alter,” a strong well-known amateur player to a match with a set of ivory club-size Staunton chessmen as a prize for the winner of the first five games.

England

Jaques “Tees Side Trophy” Set

1880

King size: 4 7/16 in.

Board: 1 3⁄8 x 23 3⁄4 x 23 3⁄4 in.

Box: 5 3⁄4 x 8 11/16 x 13 in.

Ledger: 1⁄2 x 8 1⁄8 x 6 3⁄8 in.

Ivory, felt, wood, velvet, metal, and paper

Collection of Jon Crumiller

In 1883 the Tees Side Chess Association was formed to connect the smaller chess clubs that covered Cleveland County in northeast England. As can be seen by the multitude of plaques on the box, this set served as the trophy for the association’s annual chess tournament between 1886 and 2003. The board has peg-holes on the side where pegs could be placed to keep track of wins and losses. The set was made by Jaques of London, the original manufacturer of the Staunton style, and its use as an award demonstrates how the Staunton chessmen had not only become the standard among serious chess players, but were venerated enough to be used as a trophy.

England

Jaques Chess Set

1895

King size: 4 1⁄2 in.

Box: 4 1⁄4 x 7 x 9 1⁄8 in.

Boxwood and ebony

Collection of Frank A. Camaratta

In addition to promoting the Staunton chessmen’s superior artistic forms, Howard Staunton touted their educational value for young players, specifically highlighting the helpfulness of the markers on the kingside pieces. He said, “One feature in the Staunton Chess-men is, that the King’s pieces are easily distinguishable from those of the Queen all through the longest games. Owing to the facility thus afforded for studying the best works on Chess, there can be no doubt that a young amateur, with these men, will improve much more rapidly than with the old clumsy patterns.”

Unknown

Mother of Pearl Staunton-Variant Set and Board

c 1900-1925

King size: Black: 2 1⁄2 in. White: 2 3⁄4 in.

Board: 1 1⁄4 x 10 15/16 x 10 15/16 in.

Mother of pearl, bone, wood, and felt

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Japan

Golden Castle Co., Ltd.

“The Craftsman” Staunton Pattern Chessmen

1940s

King size: 3 1⁄2 in.

Box: 3 5⁄8 x 8 x 5 7⁄8 in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Golden Castle Co. began producing chess sets in Japan in the years after World War II. “The Craftsman” was one of five sizes of Staunton chessmen the company made. They were patterned after Jaques of London’s Marshall pattern sets (a reproduction of the latter set is also on view in this exhibition). Golden Castle Co. advertised their sets in American chess periodicals Chess Life and Chess Review. All chessmen were crafted from Japanese Tsuge wood in natural and either red or black lacquered finishes, depending on the design.

England

Richard Whitty

Staunton Wooden Set and Board

1900

King size: 3 11/16 in.

Board: 1 3⁄4 x 21 1⁄4 x 18 in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

From late 19th century to early 20th century, Richard Whitty manufactured Staunton-pattern chessmen from his workshop in Liverpool at 14 Tithebarn Street. His local claim-to-fame was as a manufacturer of fancy fishing tackle, which was probably sold in his brother’s store, along with chess sets, cribbage boards, and other items. His Staunton sets are known for their large aggressive knights, as well as other characteristic features such as domed queens and red felt on the bottoms of the pieces.

England

British Chess Company Club-Size Ivory Set

1900

King size: 4 1⁄2 in.

Box: 4 1⁄8 x 6 3⁄4 x 10 3⁄4 in.

Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

England

BCC Large Stamped Board

1900

1 x 21 x 21 in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Established in 1890, the British Chess Company (BCC) only operated for about fifteen years, but in that time had a lasting impact. The company was not only a leading producer of chess equipment, but also was part of the first major attempt to standardize the rules of chess for a broad audience. These rules were first adopted by the British as the British Chess Code and later by Americans, as the American Chess Code.

The House of Staunton

Jaques 1850 Reintroduction Chess Set

2000

King size: 4 1⁄8 in.

Box: 6 1⁄2 x 10 x 14 5/16 in. Boxwood and ebony

Collection of Frank A. Camaratta

Created for Jaques of London in 2000, Frank Camaratta based the form of this set on an original 1850 Jaques chess set in his collection. He took care to reproduce the set as closely as possible.

England

Jaques Staunton Shipping/Travel Set

1900

King size: 3 1⁄2 in.

Board: 1 13/16 x 21 1⁄4 x 18 in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

With pegged pieces and accompanying holes in each of the squares to prevent the pieces from shifting, this set is ideal for travel. Jaques produced many travel sets, including one called the “In Statu Quo” that featured a unique locking mechanism that kept the pieces in place in a position during bumpy travels.

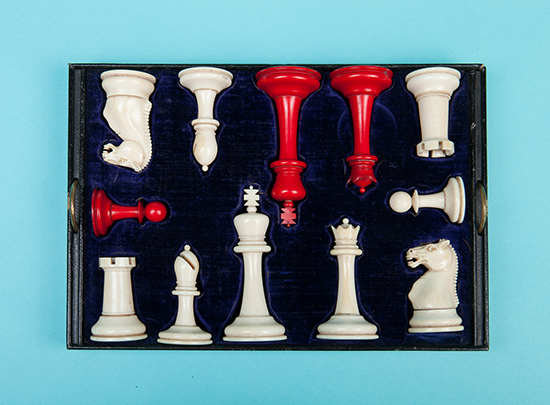

England

Jaques “Leuchars” Very Early Ivory Staunton Set

1849

King size: 3 1⁄2 in.

Box: 4 1⁄8 x 8 1⁄4 x 6 in.

Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

England

Leuchars Board

1850

11/16 x 20 1⁄4 x 21 in.

Papier mâché, leather, and gilt

Collection of Jon Crumiller

This early set of Jaques Staunton chessmen is paired with a beautiful Leuchars board, which has decorative elements that refer to chess pieces on its corners. The back of the board has paper maché decorations that complement those on the casket, or box, containing the chess pieces. Leuchars was the first retailer of Staunton chessmen, which it began selling in September 1849. It began to sell boards like this one in December 1849.

A month before the boards went on sale, an article in The Morning Herald praised the set and outlined the creators’ ambitions to promote it on both its practical and artistic merits. The article stated, “The ‘Staunton,’ so far as we can judge, seems to combine all the advantages that a chess player craves…the greatest and most significant improvement is observable in the knight…The snorting nostrils, and the curved, narrow crest, are indicated with great skill; and a more delicate and effective piece of carving could not, we apprehend, be produced. It is this piece that gives the Staunton pattern its chief distinction, and separates it from all others; and its graceful and artistical superiority is apparent at a glance.”

This selection of Staunton Chessmen and Staunton pattern sets relate to some of the most important tournaments and matches in American—and world—chess history. Though the Staunton pattern had risen dramatically in popularity during the 19th century, it was not until the 1920s that it became the standard for tournament play.

Steiner Master Chess Set

1947

King size: 5 in.

Box: 4 1⁄4 x 6 3/16 x 10 1⁄2 in.

Wood, felt, and metal hardware

Collection of Joram Piatigorsky

The Steiner Master Chess Set earns its name from its creator, 2010 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Herman Steiner. Steiner was both a talented player and a well-known promoter of chess in California. His Hollywood Chess Group attracted both celebrities like Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall and everyday players, and the connections he made among the celebrities who visited his club led him to become a “chess advisor” on several films. Steiner designed this set, with its distinctive knights. Frank Camaratta has noted that the knights resemble those from Austrian “coffee house” style chess sets, one of which is on view in this exhibition.

After Steiner’s 1955 death, his good friend U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Jacqueline Piatigorsky, herself a top American player, took over the running of his chess club, renaming it the Herman Steiner Chess Club in his honor. Some of the effects that she inherited in the process were Steiner sets like this one. Competitors in the 1963 Piatigorsky Cup, then one of the highest-rated tournaments ever held on American soil, used the sets during the competition.

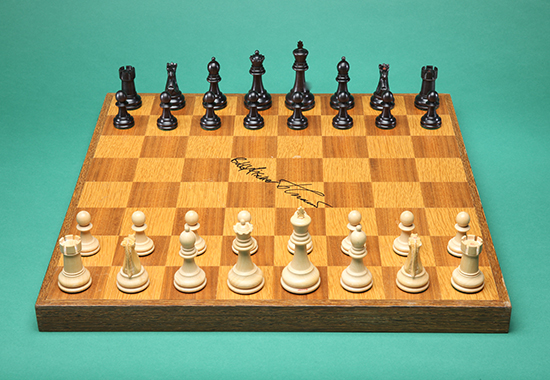

Chess Pieces from Game Three of the 1972 World Chess Championship

1972

King size: 3 5⁄8 in.

Wood

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

Chess Board Signed by Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky

1972

1 1⁄4 x 19 x 18 1⁄2 in.

Wood

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

These chess pieces bear witness to one of the most important games in the most famous World Chess Championship match—that between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky. Fischer represented the United States and Spassky the Soviet Union. The Cold War tensions between the two nations increased media coverage of the match, and Fischer’s ultimate victory served to greatly popularize the game in the United States.

Among Fischer’s demands for the match were that the players use Jaques of London Staunton chessmen for the games. With the set of Jaques chessmen on view here, Fischer defeated Spassky for the first time in his career, turning the momentum of the match. Signed by Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer, this is one of ten wooden boards created for their 1972 World Chess Championship match; however it was ultimately not used.

The House of Staunton

2013 Sinquefield Cup Chess Set

2013

King size: 3 7⁄8 in.

Box: 4 3⁄4 x 9 3⁄4 x 7 1⁄4 in.

Boxwood, ebony, and mahogany

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the Saint Louis Chess Club

In 2013, the Saint Louis Chess Club (STLCC) commissioned Frank Camaratta from The House of Staunton to create a unique chess set for the STLCC flagship event, The Sinquefield Cup (September 9-15, 2013). Camaratta made a total of 10 sets, and they are now in the collections of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield, Randy Sinquefield, Katie Sinquefield, Luke Sinquefield, World Chess Champion and 2013 Sinquefield Cup winner Magnus Carlsen, GM Hikaru Nakamura, GM Levon Aronian, GM Gata Kamsky, the Saint Louis Chess Club, and the World Chess Hall of Fame. Camaratta created the first-ever weighted DGT chess pieces for the STLCC. An imperial version of this set is also on view in this gallery.

This group of Staunton style chess sets, though much humbler than many of the others on view in this gallery, are connected to some of the figures who shaped American chess during the twentieth century. Made from humble materials and worn from many years of use, all are part of the collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame and associated with a group of influential U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductees: Edward Lasker, Arthur Bisguier, Isaac Kashdan, and John “Jack” Collins.

Edward Lasker Chess Set

Early 20th century

King size: 3 1⁄4 in.

Board: 12 3⁄4 x 12 3⁄4 in.

Boxwood, oak, birch, and walnut

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

This simple and well-loved Staunton style chess set was once owned by the U.S. Chess Hall of Famer Edward Lasker. Lasker immigrated from Germany to the United States in 1914 and quickly became one of America’s top players of the 20th century. In addition to winning five U.S. Open Chess Championships between 1916 and 1921, he made a play for the U.S. Chess Championship, narrowly losing to Frank Marshall in 1923, 8.5-9.5. Lasker is also credited with popularizing the game of chess through his many books including Chess For Fun & Chess for Blood (1942).

William T. Pinney

Pinney Club Size Chess Set

c 1930s-1950s

King: 4 11/16 in.

Wood and lacquer

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Richard Kashdan

This set tells the story of two important figures in West Coast chess: Grandmaster Isaac Kashdan and William T. Pinney. Kashdan, who once owned this set was one of the top five chess players in the world during the 1930s. Kashdan later was the chess columnist for the Los Angeles Times and organized the Lone Pine International chess tournaments. Pinney, one of the first individuals to mass produce chess sets in the U.S., advertised the unique sets in Chess Review. Some aspects of the designs of the pieces hinted at their movement—eight nicks in the knight’s mane indicate it can move to eight squares, eight nicks in the queen’s crown show that she can move in eight directions. This style of set was used in chess clubs and tournaments across the U.S. in the 1930s-50s.

Arthur Bisguier’s Chess Set

Date unknown

King size: 2 1⁄2 in.

Plastic

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Arthur Bisguier

Considered to be one of the most friendly and outgoing of American Grandmasters, Arthur Bisguier will be remembered for not only winning three U.S. Open Chess Championships, participating in two Interzonals and playing on five American Olympiad teams, but also as one of the great chess ambassadors. For over half a century, Bisguier regularly gave lectures and played simultaneous exhibitions at chess clubs, schools, and prisons around the United States. Before he died in April 2017, Arthur Bisguier was the world’s oldest active GM. Bisguier was an active chess player for most of his life, after teaching himself chess, he earned the title of International Master in his early 20s. In 1950, at the age of 28 he achieved the title of Grandmaster.

A.G. Spalding & Bros.

John Collins’ First Chess Set and Box

Date unknown

King size: 3 in.

Box: 2 5⁄8 x 8 x 5 1⁄2 in.

Wood and lacquer

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

John “Jack” Collins served as mentor to a number of important American chess players, including Donald and Robert Byrne; William Lombardy; and most famously, Bobby Fischer. Before his success and fame in chess, Collins learned the game as a child from his family landlord Fredrick Huhn. After learning the basics, and no doubt acquiring this set, Collins, in turn, taught five other boys. Together the small band started the Hawthorne Chess Club, named after the street where Collins grew up. The club grew quickly and soon started to compete with other clubs from the area, starting the Brooklyn chess league. The culmination of these events marked the beginning of both Collins’ career as a chess player and teacher. These well-worn Staunton pieces testify to his lifelong love of the game.

Pre-Staunton Sets

These sets are examples of many of the styles that proliferated throughout Europe and around the world before the dominance of the Staunton chessmen. Some of the styles on view contain delicate elements that could easily be damaged, while some others have pieces that are hard to distinguish from each other. When promoting the Staunton chessmen, Howard Staunton stressed these points, stating, “In the simplicity and elegance of their form, combining apparent lightness with real solidity, in the nicety of their proportions one with another, so that in the most intricate positions every piece stands out distinctively, neither hidden nor overshadowed by its fellows, the ‘Staunton Chess-men’ are incomparably superior to any others we have ever seen.” However, another reason for the eventual success of the Staunton sets may have been the simplicity of their design, which made them easier to reproduce than many of their predecessors and competitors.

Italy

Italian 18th Century Set

1790

King size: 3 in.

Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

France

French Diderot Set

1730

King size: 3 ½ in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

England

Washington Set

1775

King size: 3 ½ in.

Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

France

French Directoire Set

1780

King size: 3 1⁄2 in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

France

French Regence Set

1850

King size: 3 13/16 in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Middle East

Islamic Red and White Ivory Set

1800

King size: 1 ⅝ in.

Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Germany

Selenus Bone and Horn Set

1875

King size: 4 9/16 in.

Bone and horn

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Germany

German Playing Set

1790

King size: 3 1⁄2 in.

Bone

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Germany

Selenus Set

1790

King size: 4 5/16 in.

Bone

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Europe

European Ivory Playing Set

1800

King size: 3 1⁄2 in.

Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

England

Jaques Signed St. George Set

1840

King size: 4 3⁄8 in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

England

Thomas Lund

Antique Ivory Chess Set

1840

King size: 3 ½ in.

Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

England

Lund Style Unstamped Set

1850

King size: 2 13/16 in.

Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

England

Victorian Bone Playing Set Retailed by Rhoads

1850

King size: 3 ½ in.

Bone

Collection of Jon Crumiller

20th Century Staunton Sets

This grouping of chess sets from the early and mid- 20th century demonstrates the liberties that chess set creators took with the then-familiar pattern in the decades following its introduction. Even creators who used a traditional medium—ivory—to create their pieces, played with the proportions of the pattern to create new and sometimes decorative versions of it. Other makers, like E.S. Lowe Company and Gray’s of Cambridge, took advantage of cutting-edge materials to create Staunton sets unlike those that had been produced before.

England

Staunton Ivory Set by Asprey

1960

King size: 5 in.

Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Founded in 1781, Asprey & Co. is a retailer of luxury home goods like this elegant ivory chess set. As the sellers of high quality and high priced items, this ivory set sold by them demonstrates a demand for grandeur within the confines of the Staunton design.

South America

Tagua Nut Staunton-Variant Set

c 1900-1950

King size: 3 5/16 in.

Tagua nut

Collection of Jon Crumiller

This charming Staunton variant set, which features chunky pieces, is made from tagua nut. Tagua nut is often referred to as “vegetable ivory” due to it having a similar appearance and texture to animal ivory. It is a material for small sculptures, and around the era that this set was made, was also used to create buttons.

United States

Lowe’s Catalin Set

c. 1940s

King size: 3 11/16 in.

Catalin

Collection of Duncan Pohl

The E.S. Lowe Company, which was founded in 1929-30 and based in New York, created a number of games including Bingo and Yahtzee. Chess and checker sets were their best-selling products. The Lowe Company produced many of the mass- produced sets that the American public would have been familiar with in the mid-20th century. This set was one of their more upscale styles, and was sold in a presentation case that was advertised in the 1940s in the American chess periodical Chess Review. The company eventually sold to Milton Bradley in 1973, just a year after chess increased in popularity in the United States following Bobby Fischer’s victory in the 1972 World Chess Championship.

England

Gray’s of Cambridge

Silette Catalin Staunton-Variant Set 1927

King size: 2 13/16 in.

Box: 2 11/16 x 3 11/16 x 6 11/16 in.

Catalin

Collection of Jon Crumiller

The creators of this set, Gray’s of Cambridge, interpreted the traditional Staunton set using a then-new material: catalin. Catalin was a new type of plastic that could be easily shaped, in this case, to create silhouettes of the familiar Staunton chessmen. The Catalin Corporation patented the material and it was used in the creation of a number of objects, including radios.

England

The Rose Chess Staunton-Variant Set

1940

King size: 2 1⁄2 in.

Box: 1 3⁄4 x 4 5⁄8 x 7 1⁄8 in.

Lead

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Like the Silette Catalin Staunton Variant set on view in this case, the Rose Chess Staunton Variant interprets the Staunton set in silhouette form. The set is named for Mildred Rose, the owner of The Rose Chess Company. This set is especially unique because it was never removed from its case, which even contains the original tissue paper around the pieces.

Mass-Produced 20th Century Staunton Sets

Advances in technology meant that during the 20th century chess sets could be mass-produced, making the game accessible to a wider audience. In the early 20th century, most of the wooden chess sets sold in the United States were imported from other countries. However, a number of businesses like WM. F. Drueke & Sons, the E.S. Lowe Company, Windsor Castle Company, and the Pacific Game Company began producing plastic sets, which were advertised in Chess Life and Chess Review beginning in the 1940s. While Bobby Fischer famously demanded Jaques of London Staunton pieces for the 1972 World Chess Championship match, from the 1950s to the early 1970s, he was often photographed playing with sets like those made by Windsor Castle and Drueke that are on view here.

United States

Drueke Players’ Choice with Wooden Box

c 1964-87

King size: 3 3⁄4 in.

Plastic

Collection of Duncan Pohl

Founded in 1914, Drueke is a manufacturer of chess sets as well as other games. During the 1940s, the company filed a series of patents for chess set designs. This set, called the Player’s Choice, was introduced in 1965 at the National Open in Las Vegas, Nevada. The knights closely resemble the design of those in the company’s logo. It was often advertised in Chess Life magazine.

W. M. F. Drueke & Sons

Chessmen No. 21

Date unknown

King: 2 1⁄2 in.

Box:21/4×31⁄8×53⁄4in.

Plastic

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Patented in 1941, the American Design chess set features pieces with unique octagonal shafts. The set was designed by Charles B. Chatfield and sold in both weighted and unweighted versions and in many colors, including red and white, black and white, and the brown and white version seen here. The set is even accompanied by its original box.

K & C Ltd. London

Chessmen

Date unknown

King size: 2 3/16 in.

Box:21/16 x3x57⁄8in.

Wood

Collection of the World Chess Hall Fame

Nation Time Inc.

Nation Time Chess Game

1976

King: 3 3⁄4 in.

Plastic and felt

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

While many of the sets in this case resemble traditional versions of Staunton pattern sets, the creator of Nation Time sought to overhaul both the looks of the pieces and the rules of the game, giving it symbolic meaning during the era of the Black Power movement.

The black pieces move first and are red, black, and green, symbolizing the blood of slaves and the contributions of African Americans to the United States, the African continent, and birth, respectively. The red, white, and blue pieces represent people who sacrificed their lives in the struggle for independence, the ground where Revolutionary War battles were fought, and “the universe of mankind where each individual is endowed by his Creator with certain inalienable rights. The pieces also featured different names and some rules different than the traditional ones.

Cavalier Chess Set

1967

King size: 4 in.

Plastic

Collection of Duncan Pohl

Pacific Game Company

Cavalier Chess Set No. 1422

1973

King size: 2 7⁄8 in.

Plastic

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

OKUMA America Corporation

Machined Commemorative Set

2007

King: 2 7⁄8 in.

Board: 1 5⁄8 x 15 x 15 in.

Aluminium and brass

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Hartwig Inc.

This selection of chess pieces shows some of the sets that were popular in the United States during the 20th century as well as a unique interpretation of the set created during the 21st century.

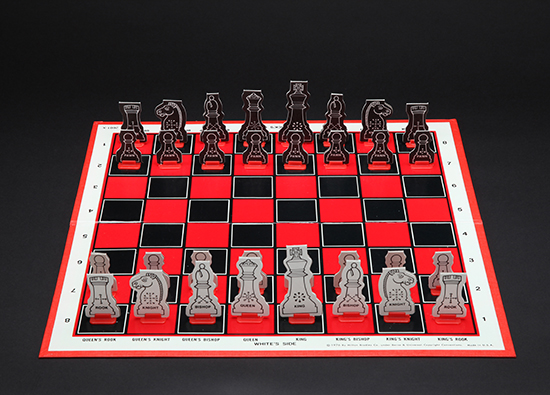

E.S. Lowe Company

Tournament Chess Tutor Set

1976

King size: 3 1⁄8 in.

Board: 15 1⁄4 x 15 1⁄2 in.

Cardboard, paper, and plastic

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Leo Gladstone

Windsor Castle Chess Set

c 1940-50s

King size: 3 3⁄4 in.

Box: 2 1⁄2 x 15 3⁄4 x 10 1⁄4 in.

Plastic

Collection of Duncan Pohl

20th Century Staunton Playing Sets

At the turn of the 20th century, Jaques of London faced many competitors. Many produced their own interpretations of the Staunton pattern, some with new materials and others with distinctive forms.

The House of Staunton

Jaques 1930 Reproduction Chess Set

1930

King size: 4 1⁄2 in.

Boxwood and ebony

Collection of Frank A. Camaratta

The House of Staunton

Marshall Series Staunton Chess Set

2016

King size: 4 in.

Boxwood and ebony

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of House of Staunton, Inc.

Produced by House of Staunton, this Marshall series chess set is modeled on turn of the 20th-century chess sets made by Jaques of London. Frank Camaratta founded The House of Staunton, which produces both many original designs and reproductions of antique patterns. The House of Staunton donated this set to the World Chess Hall of Fame following Howard Staunton’s 2016 induction to the World Chess Hall of Fame.

American Chess Company

Staunton Style Chess Set

c 1900s

King size: 3 1⁄8 in.

Boxwood and ebonized wood

Collection of Alan Buschmann

American Chess Company

Staunton Style Chess Set

c 1900

King size: 2 5⁄8 in.

Boxwood and ebonized wood

Collection of Alan Buschmann

American Chess Company

Staunton Style Chess Set

c 1900

King size: 4 in.

Boxwood, ebonized wood, and leather

Collection of Alan Buschmann

American Chess Company

Staunton Style Chess Set

c 1900

King size: 4 in.

Boxwood and ebonized wood

Collection of Alan Buschmann

The American Chess Company began advertising chess sets in American Chess Magazine in 1897. Some of the advertisements contained illustrations of the sets, showing their distinctively charming “sawtooth” mane knights. It is unknown whether the American Chess Company manufactured the sets itself, or whether it simply served as a distributor. However, some of the sets were used by some of the top players of the era in important competitions. Frank Marshall (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 1986) and Emanuel Lasker (World Chess Hall of Fame, 2001) used an American Chess Company set in their 1907 World Chess Championship match. A set like this one, with different knights, was used during the 1904 Cambridge Springs International Chess Congress, which was won by Frank Marshall.

Austria

Austrian Coffeehouse Staunton-Variant Set

c 1900-1925

King size: 3 7⁄8 in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Influenced both by the Staunton pattern and Central European patterns, the Austrian Coffeehouse Set was the standard style for play in Central Europe during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Players used it in major tournaments including Vienna 1898, Semmering 1927, and Karlsbad 1929. The dramatically curved necks of the knights may have influenced the Steiner Master Chess Set (also a part of this exhibition), which was designed by 2010 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Herman Steiner.

American Chess Company

Staunton Style Chess Set

c. 1900

King Size: 2 1⁄2 in.

Boxwood

Collection of Alan Buschmann

England

B & Co. Staunton Set

1920

King size: 3 1⁄8 in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Little is known about the manufacturer of this handsome B & Co. Staunton pattern set. The pieces feature red indicators for the kingside pieces. While Jaques had introduced the standard of marking the kingside knights and rooks, this practice was soon copied by other manufacturers.

England

British Chess Company “Improved Royal” Set

1900

King size: 3 7⁄8 in.

Wood and Xylonite

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Founded by William Moffatt and William Hughes, the British Chess Company (BCC) aspired to compete against Jaques of London in producing high-end chess sets. The company began manufacturing sets in 1891. This design contains one of BCC’s major design innovations: the use of xylonite, an early plastic, to create the heads of the knights. Unlike other pieces in a high-end chess set, knights are carved rather than turned on a lathe; using xylonite allowed BCC to mold rather than carve the knights, decreasing the cost and time of creating them.

19th Century Staunton Sets

The Staunton chessmen debuted in mid-19th century London, a center of chess activity as well as manufacturing and trade. One of the Staunton patterns’ influences as well as sets by many of Jaques’ competitors are on view in this case.

England or Scotland

Wooden Edinburgh Set

1840

King size: 4 3⁄8 in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Although generally described as a radically new design for their time, the form of the Staunton was based on the earlier Edinburgh chessmen which were designed in the 1840s by Lord John Hay. The sets have simple columns and are differentiated by height. The Edinburgh pattern was a popular style of chess set, and many English manufacturers, including John Jaques, produced chessmen in the pattern.

England

Philidor Set by George Merrifield

c 1850

King size: 3 15/16 in.

Boxwood and ebony

Collection of Jon Crumiller

The Philidor chessmen, named after 18th-century composer and chess player François-André Danican Philidor, were introduced in 1850 to compete with the Staunton style as the set of choice among tournament players. Unfortunately for its creator, George Merrifield, it was a failure and manufactured for only about a year, and only a few remaining sets of this kind are now known to exist.

England

Hallett of High Holborn Staunton-Pattern Set

1850

King size: 3 1⁄4 in.

Wood

Collection of Jon Crumiller

This Staunton-pattern set bears the influence both of Staunton chessmen and the earlier Edinburgh pattern. The slender rooks and queens topped by spheres are similar to those in the Edinburgh set on view in this case. The maker of this set was probably William Hallett, whom operated Hallett’s Ivory Turning Manufactory at 83 High Holborn Street in London. There, he produced sets from ivory, wood, and bone, as well as performed chess set repairs and taught ivory turning. Hallett also sold patent medicines.

Edwards & Jones Ivory Set

1875

King Size: 3 11/16 in.

Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Based on Regent Street in London, Edwards & Jones was a manufacturer of ivory and tortoiseshell products. These included chess sets like this one, as well as mirrors, brushes, glove stretchers, paper knives, and watch stands. They also sold leather bags and stationery.

England

Alabaster Staunton Set

c 1850-1875

King size: 3 11/16 in. Alabaster

Collection of Jon Crumiller

United States

Bird’s Staunton Chessmen

1890

King size: 4 5/16 in.

Wood and metal

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Henry Edward Bird, a well-known English player and chess author during the 19th century, promoted this unique set. Advertised as “a great improvement on Staunton’s design,” the set has metal knights. Like the British Chess Company, which made knights from an early type of plastic, the manufacturers of this set may have been trying to address the problem of the expense of carving knights.

China

Cantonese Ivory Staunton Set

c 1875-1900

King Size: 3 1/2 in.

Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

The finest chess sets in China were manufactured in Canton, where this elegant set was created. The British introduced Europeanized chess to China in the late 18th century, when they established trade networks in the country. Chinese ivory artists soon began producing gorgeous chess sets both for export and visiting tourists.

England

Victorian Ornamental Staunton Set

c 1850-1875

King size: 4 1⁄2 in.

Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

The Victorian Ornament Staunton Set represents a decorative variation of the Staunton style chess set. Though adorned with decorative surface textures, this set maintains the essential qualities of the Staunton pattern’s forms.

China

Chinese Export Staunton-Variant Set

c 1850-1875

King size: 3 7⁄8 in.

Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

England

Jaques Custom-made Set, possibly Howard Staunton’s Personal Set

c 1850-75

King size: 5 1⁄2 in.

Ivory

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Originally, the Staunton chessmen were sold in two sizes: a Standard size (8.9 cm) and a Full Club size (11 cm king) only. This set’s enlarged scale with a 14 cm king may indicate that it was created for an important client. This set is the subject of debate: while some of the world’s top experts in the sets believe it to have been Staunton’s own set, its current owner believes that it could have been made for another individual.

Paper Artifacts & Illustrations

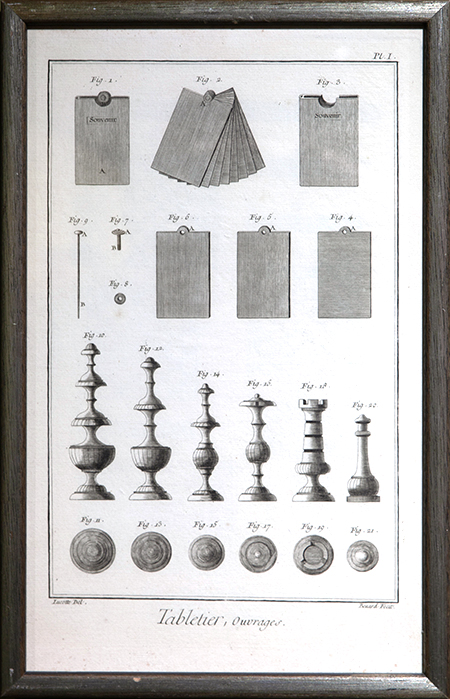

France

Diderot Encyclopedia Print

1776

14 ¾ x 9 in.

Paper

Collection of Jon Crumiller

A successful philosopher, art critic, and writer, Denis Diderot compiled and published an encyclopedia of crafts between 1751 and 1772. The finished product included 17 volumes of text and 11 volumes of illustrations. It had an enormous impact on both 18th-century audiences and modern-day scholars interested in learning about the techniques of artists and craftsmen of the period. These two pages of engravings depict chess pieces and game boards. A chess set created from this pattern, one of the many that flourished before the creation of the Staunton set, is also a part of The Staunton Standard: Evolution of the Modern Chess Set.

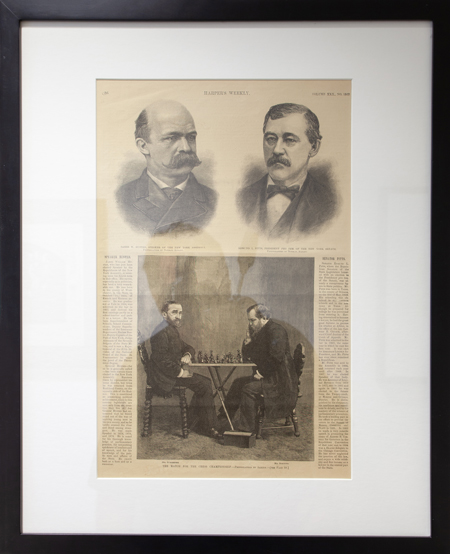

Harper’s Weekly Vol. 30, No. 1517

January 16, 1886

15 ⅞ x 11 ⅛ in.

Magazine

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

One of the early highlights in Saint Louis’ chess history was also a landmark event in United States and global chess history. The city served as one of three hosts for the 1886 World Chess Championship—the first ever held. Wilhelm Steinitz (U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 1986; World Chess Hall of Fame, 2001) faced off against Johannes Zukertort (World Chess Hall of Fame, 2016). The match took place in three American cities—New York (January 11-20), Saint Louis (February 3-10), and New Orleans (February 26-March 24). Steinitz, who lost four of the first five games in New York, won three of the four games played in Saint Louis, setting the stage for his ultimate victory in the match. In this image the players can be seen using Staunton chessmen.

First American Chess Congress, New York

1857

23 x 18 in.

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Frank A. Camaratta

The first American Chess Congress was organized by Daniel Willard Fiske and Thomas Frere and held in New York City from October 6 to November 10, 1857. The tournament was designed after the London format and the 16 best American masters were invited to participate in the event. Of these Paul Morphy was included and he dominated the competition. Despite the first prize being $300, Morphydid not accept money for chess accomplishments. He instead accepted a silver tray, pitcher, and four goblets (on display at the Saint Louis Chess Club and in the collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame). His victory here marked him as one of the best players in the world.

Staunton Pattern Registration Drawing

March 1, 1849

11 x 17 in.

Reproduction of drawing

Courtesy of the National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom

Architect Nathaniel Cooke (his name is spelled incorrectly in the drawing) registered the Staunton pattern in 1849. This registration drawing depicts each of the chessmen as well as the markings on the tops of kingside knights and rooks, most likely at the insistence of Howard Staunton, who had long advocated distinguishing kingside knights and rooks with a special mark to aid in playing over games written in descriptive notation.

David Levy photograph of lithograph by M. Laemlein, after painting by M. Marlet

Match, H. Staunton vs. P. C. F. Saint-Amant, Paris

1843

39 x 30 in.

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of Frank A. Camaratta

While Howard Staunton was already a well-known player by the time he competed against French player Pierre Charles Fournier de Saint-Amant in the match seen here, it was this event that marked him as one of the best players of the era. Both Staunton and Saint-Amant were known as top talents in their respective home countries and both were writers as well as players. They played two matches in 1843—the first, held in London, was won by Saint-Amant. Staunton won the return match. His victory was a source of national pride for members of the English chess community.

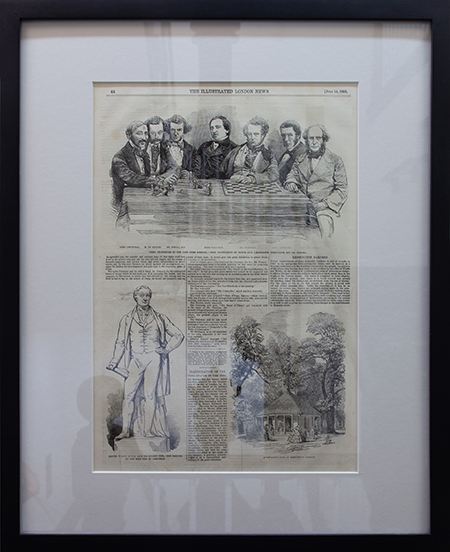

The Illustrated London News

Artist unknown

Chess Celebrities at the Late Chess Meeting

July 14, 1855

15 ⅝ x 10 ¾ in.

Magazine

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Though Howard Staunton had earned enough standing in the chess world to use his name to promote a chess set by 1849, his early years and background are largely a mystery, and “Howard Staunton” is possibly a pseudonym. He first appears in the historical record in 1836, when his name was recorded in a book of games by a prominent chess player and in chess periodicals. Within only five years, he was both recognized as a prominent English player and had founded the first English-language chess periodical. Staunton was a controversial figure during his own era, sometimes alienating other members of the chess world by using his chess column to further conflicts with other players. Nevertheless, he also earned acclaim for his play as well as his efforts to standardize the rules of the game and organizing the first international chess tournament.

England

Staunton Handwritten Letter

August 2, 1847

7 x 4 ⅜ in.

Paper

Collection of Jon Crumiller

Howard Staunton, who lent his name to the style of chess set that would become the international standard, was one of the world’s strongest chess players in the mid-19th century. With characteristic false modesty, belied by the “Chess Champion” stationery on which the note is written, he composed this letter, dated August 2, 1847. The body of the text reads, “Sir, my signature is too unimportant to add any value to a collection of autographs of distinguished persons, but it is quite at your service. Believe me.”

England

Staunton Handwritten Letter

1857

7 x 9 in.

Paper

Collection of Jon Crumiller

In this letter, Howard Staunton writes to an organizer of the 1857 American Chess Congress. He speaks of his hopes for the event to further promote interest in the game in the United States. Staunton also included a rough proof of his forthcoming additions to The Chess-Player’s Handbook in order to receive feedback from the players in the tournament. The event included a number of prominent chess players and was won by Paul Morphy.

PRESS

7/25/2018: Business Journal — Photos: See 3 New Exhibits at World Chess Hall of Fame

5/13/18: The Herald Dispatch — Jean McClelland: Knowing where a chess set is from can help determine its current value

4/24/2018: Art Daily — Three groundbreaking chess exhibitions open at the World Chess Hall of Fame

4/5/2018: St. Louis Public Radio — On Chess: The 169-year-old modern chess set

3/22/2018: Press Release — New Exhibition at The World Chess Hall of Fame Explores the History of Staunton: The Game’s Most Iconic Set