May 14, 2015 - October 18, 2015

Encore! Ivory Chess Treasures from the Jon Crumiller Collection

Encore! Ivory Chess Treasures from the Jon Crumiller Collection revisits one of the most stunning chess collections in the United States. Focusing solely on antique ivory sets and boards, this exhibition showcased the incredible range and use of the highly sought-after and now, very controversial medium.

Exhibit Overview

Used for thousands of years to create decorative and utilitarian objects, ivory’s monetary value is reflected in its nickname “white gold.” Skilled artisans have transformed the tusks of mammoths, elephants, and walruses (among other animals) into highly decorative and prized possessions. The material’s creamy white color and hard texture lent itself well to the creation of musical instrument components, religious icons, combs, jewelry, and gaming pieces—especially chess sets and embellished boxes and boards. Artists and craftspeople created both solid, simple playing sets and elaborate and delicately carved ornamental sets from the treasured material.

This exhibition showcases ivory pieces and related objects from one of the greatest collections of chess sets in the United States. They date from the 16th through 20th centuries. By examining the over 80 chess sets, and numerous boards and tables included in Encore! Ivory Chess Treasures from the Jon Crumiller Collection, visitors to the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) were able to study the evolution of the game of chess during this time, appreciate the fantastic craftsmanship of each object, and learn about different artistic techniques from cultures around the globe. This exhibition also created a discussion about the beauty and cultural value of the antique sets as well as the importance of laws that safeguard the remaining animal populations.

In 1800, the global elephant population is estimated to have numbered 26 million. However, during the same century, demand for ivory in Europe rose dramatically. In 1890, London, England, alone imported 700 tons of ivory, derived from the tusks of approximately 14,700 elephants. Mass production of utilitarian objects from ivory further fueled the killing of elephants through the twentieth century. In the 1970s and 1980s, a conservation crisis inspired new restrictions on the ivory trade, designed to combat the rapid decline in elephant populations, which had declined to 1.3 million by 1979. In 1975, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) banned international trade in Asian elephant ivory, and in 1989 expanded this prohibition to African elephant ivory. Over the subsequent decade, elephant populations in some areas rebounded.

Driven both by expanding demand for ivory due to increased prosperity and lax enforcement of laws regarding the sale of ivory in China, poaching of African elephants has again risen dramatically since 2005. In the United States, the terrible possibility that African elephants could become extinct in the matter of a decade, has led to tighter restrictions and new regulations banning trade in antique African elephant ivory. A 2013 Executive Order by President Barack Obama initiated these efforts. The first limitations eliminated the commercial and non-commercial import, export, transfer, and sale of objects at least 100 years old.

Over the last several months, restrictions have been loosened on the non-commercial movement of the prized medium, allowing musicians to travel with instruments containing ivory. However, New York and New Jersey laws have become more restrictive, also banning the sale or trade of mammoth and mastodon ivory. Not only have these changes affected collectors of objects, such as chess sets, but they have also significantly impacted museums and musicians. Collectors, including those of chess sets, saw their entire cache of ivory become valueless. Some professional musicians expressed concern for their livelihoods as well as about the possibility that musicians would no longer be able to use the best instruments in the United States after the commercial transfer of prized antique instruments incorporating ivory became impossible.

The debate is complex. Those who promote the ivory ban argue it is necessary to save not only thousands of African elephant lives, but also the lives of the park rangers who protect them. Only by completely closing avenues for ivory to be sold can they safeguard these animals. Others argue that the illegal ivory trade sometimes supports terrorist networks. Those who argue against the ban claim that the ivory restrictions may harm elephants by further pushing the trade underground, increasing the danger and raising the black market value of ivory. Some state that the laws are unfair to collectors of antique ivory, prevent the preservation of important art and historical artifacts, and do not do enough to stop poachers from killing elephants. The coming years will prove crucial to people on both sides of the debate, as global populations of endangered species are monitored and as collectors and museums evaluate the effects of the laws upon the preservation, exhibition, and transfer of ivory artworks and artifacts.

—Shannon Bailey, Chief Curator, and Emily Allred, Assistant Curator

From the Collector

It’s a privilege to be able to exhibit these antique works of art at the World Chess Hall of Fame. The chess sets in this exhibition need little introduction because they speak for themselves: they are timeless masterpieces from centuries past, making their reappearance on the public stage for the first time in many years. It is important to note that the ivory items in this exhibition have been legally confirmed as antique, meaning over 100 years old, by CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) and by the United States Fish & Wildlife Service, the federal agency whose mission is to preserve and protect endangered species.

An exhibition of ivory items might be considered controversial. Indeed, any modern-day reference to elephant ivory must be taken within a larger and more important context: the world’s elephants are under attack, and their very survival is threatened. As the chosen stewards of our planet, it is our duty to protect these majestic, intelligent, and sophisticated creatures from the snares of increasingly brazen and violent poachers. That mandate is incontrovertible. Taking it a step further, some people feel that all ivory artifacts—whether two years old or two hundred years old—should be immediately and permanently removed from our society.

With that in mind, one might be inclined to wonder why my collection includes (and even highlights) antique ivory chess sets. The reason is simple and straightforward. Many collectors of antique items, such as museums, private collectors, and institutions of higher learning, seek to acquire the best-possible expressions of art—those rare, crowning achievements of artistic talent, skill, and craftsmanship. For chess sets and other ornamental items of prior centuries, ivory was the definitive choice of the master artisans; it was exotic, readily carved, durable, and perfectly weighted, with a glossy appearance, smooth and solid to the touch. So the acquisition of a top-tier antique chess set is, in almost all cases, the acquisition of a top-tier antique ivory chess set.

Yet today, elephants are being hunted and struck down so that their tusks can be exported and converted into mass-produced trinkets, offered for sale in tourist shops and flea markets in Asia and around the world. How to reconcile the difference between these two diametrically opposed scenarios?

An important distinction needs to be made between the present and the distant past. To state an obvious but overlooked fact—we can diligently strive to save the elephants of today and tomorrow, but we can’t save the elephants of yesteryear. Another consideration, also obvious and also overlooked, although I imagine that we would all agree with it, is this: a defining characteristic of who we are, the human race, is that we take great measures to protect our cultural history, as captured by the artistic expressions of master artisans throughout the ages. The chess sets in this exhibition are part of those masterful artistic expressions, and are part of our cultural history. So while it is mandatory that we take all possible steps to preserve the world’s elephant population, I would submit that it is also important to preserve our artistic heritage, even when the chosen artistic medium of the time is one that cannot be obtained, legally or morally, today. True, the first goal is more acclaimed and more urgent than the second, but there is no reason to sacrifice an essential part of our heritage, as evidenced by these works of art, due solely to the unscientific perception that such a sacrifice would somehow promote the preservation of today’s elephant population. It doesn’t. The two objectives are entirely separate, and both can be met simultaneously.

I hope you enjoy the exhibition. If you have any questions, whether about the chess sets or the controversial substance from which they are made, I invite you to attend and participate in an upcoming lecture on August 29, 2015, at the World Chess Hall of Fame, during which I’ll discuss chess artifacts and answer your questions. Meanwhile, I think you will agree that these works of art still evoke feelings of excitement and awe, as they did in their original days of glory, one or more centuries ago.

—Jon Crumiller, 2015

Jonathan Crumiller

A longtime chess fan and competitor, Jon Crumiller purchased his first antique chess set online in 2002. This acquisition quickly sparked a passion, and Jon’s collection of antique sets now numbers over 600. It includes sets originating from over 40 countries, dating as early as the 11th century (and gaming pieces dating to 3000 BCE), unique sets owned by 18th- and 19th-century royalty, and made from materials such as jade, silver and gold, bone, wood, and precious stones among others. The scope of his collecting has also grown to include chessboards, timers, and chess miscellanea, mainly from the 19th and 20th centuries. Now recognized as one of the greatest chess set collections in the world, the artifacts he has gathered serve as a visual history of the diverse ways that cultures across time and around the world have interpreted the game of kings. A portion of the Crumiller collection was first shown in the World Chess Hall of Fame’s 2013 exhibition Prized and Played, which included notable ornamental and playing sets.

Not only interested in acquiring artifacts but also learning about their origins and histories, Jon conducts research on the evolution of chess set styles, usage, and manufacturing. He shares this information with the global community of collectors, including his fellow enthusiasts in Chess Collectors International. Through his website www.chessantique.com, Jon provides curious chess devotees from around the world with beautiful photos of his stunning collection as well as some of the fruits of his meticulous research.

Jon’s tournament experience stretches back to the Bobby Fischer-boom years in the early 1970s, and includes a Delaware State Championship title and numerous other victories. Along the way, he has earned the United States Chess Federation National Master title in both over-the-board and correspondence chess. Still active via online chess, Jon credits much of his middle-age chess improvement to the outstanding teaching skills of his chess teacher and friend, U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee Grandmaster (GM) Lev Alburt. Jon relishes the occasional opportunity to play with, and against, some of the top players in the world. He teamed up with World Chess Hall of Fame inductee and former World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov in London for a charity game versus Team GM Nigel Short, and managed to eke out a draw against World Chess Champion Magnus Carlsen in a simultaneous exhibition. A one-on-one game versus former World Chess Champion Vladimir Kramnik did not finish with such a successful result! Ever the competitor, Jon remarks that one of his favorite ways to end a game is by winning.

Jon and his wife Jenny live in Princeton, New Jersey, and have three children and two grandchildren. Jon is Co-founder and Chief Operating Officer of Princeton Consultants Inc., a mid-size consulting firm that specializes in business optimization and operational efficiency. Jenny is an elected official on Princeton Council, the governing body of Princeton, New Jersey.

Works Featured in the Exhibition: German

Germany

German Mythological Ivory Set, 1900

King Size: 3 3⁄4 in.

Ivory

Pieces based upon famous works of classical sculpture communicate the taste and education of the patron who purchased this chess set. The Apollo Belvedere appears as the king, while Venus de Medici represents the queen. As the bishop, the messenger of the gods, Hermes, rests his attribute, a caduceus, or winged staff with two snakes wrapped around it, on his shoulder. Each of the eight pawns is a different putto in action: one holding a goose by its neck, another bearing an archer’s bow, and yet another carrying a bundle of grain.

Germany

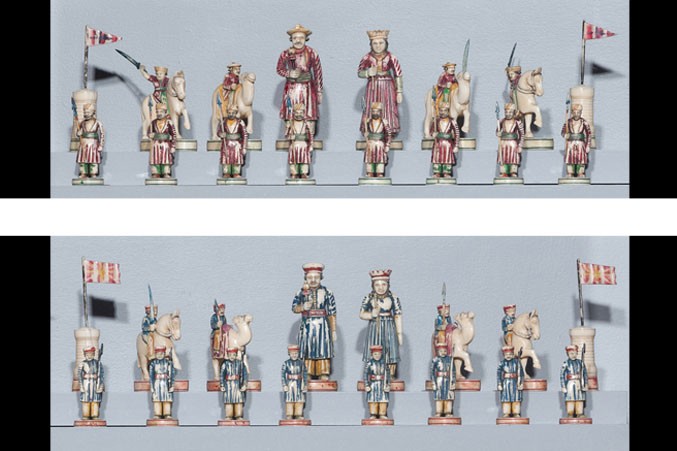

German Polychrome Ivory Figural Set, 1790

King Size: 3 5⁄8 in.

Ivory

This late 18th-century set represents two regional German armies. Although the polychrome has mostly worn away with time, evidence of their previous coloring remains in and around the deeper indentations in the pieces. The rooks feature elephants carrying towers, possibly referring to chess’ historical roots in India. There, elephants represented the rook in early predecessors of the game. One has a lookout, watching for attacks from the other army.

Germany

German Red and White Figural Ivory Set, 19th Century

King Size: 3 in.

Ivory

Animated expressions as well as finely textured garments elevate this delightful German set. Each of the pieces bears attributes of their position: the king and queen hold scepters, symbols of their power, while the page clutches a scroll, and the knight rides on the back of a dramatically rearing horse. The pawns hold spears, swords, and staffs.

Germany

Geislingen Ivory Set, 1790

King Size: 2 3⁄4 in.

Ivory

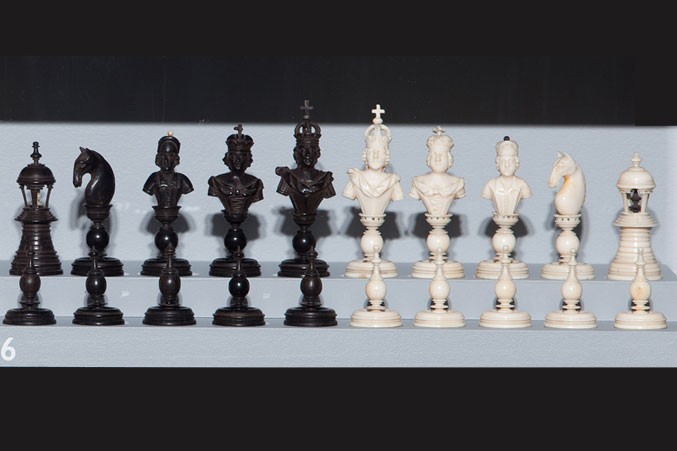

Made in Geislingen, Germany, this ivory chess set depicts three quarter bust-length views of a royal court with nonfigurative pawns. Each sits atop a petaled base with decorative cross hatching on a tall, slender column. Due to stylistic similarities with those created in Dieppe, France, sets of this type were once believed to have been created there.

Germany

German Ivory Bust Set, 1860

King Size: 3 3/4 in.

Ivory

The carver of this masterful German set paid great attention to detail in the costumes of the members of the court. Each includes carefully sculpted details like jewelry, elaborate headpieces, and delicate lace. The infantrymen wear ivory representations of metal morion helmets, which were generally used during the 16th and 17th centuries.

Germany

German Ivory Figural Set, 1850

King Size: 3 1/3 in.

Ivory, wood

Often, craftsmen would save their skill and expertise for decorative chess sets. However, this German ivory set was designed for travel rather than display, yet the artisan depicted an unusual level of detail in the faces and clothing of the bishop, queen, and king. The rook is represented as a tower with an open space where the watchmen would keep post. The “bishop” appears here as a page, sometimes a court messenger, a reference to the piece’s German name, läufer, or runner.

Germany

German Double-Knight Ivory Set, 1800

King Size: 4 1/2 in.

Ivory

The double-headed knights in this set are characteristic of a regional style of chess set that flourished in lands ruled by the Habsburg Empire, as well as Germany, in the 19th-century. The double-headed knight was so closely associated with chess sets from this region that the Hanover Turner’s Guild, an association of artisans in the city of Hanover, Germany, illustrated it on their seal.

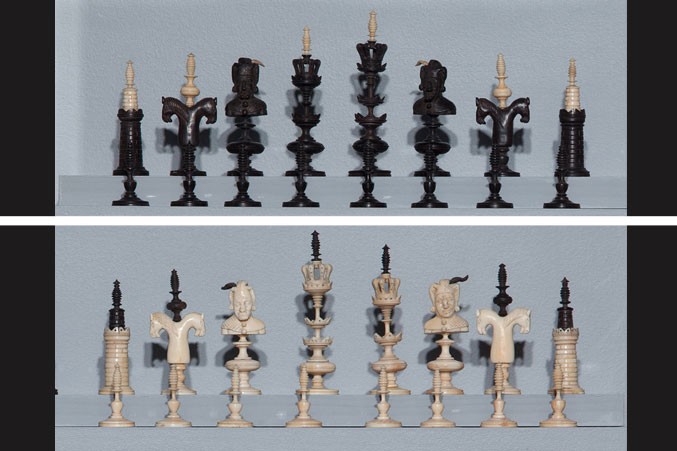

Germany or Netherlands

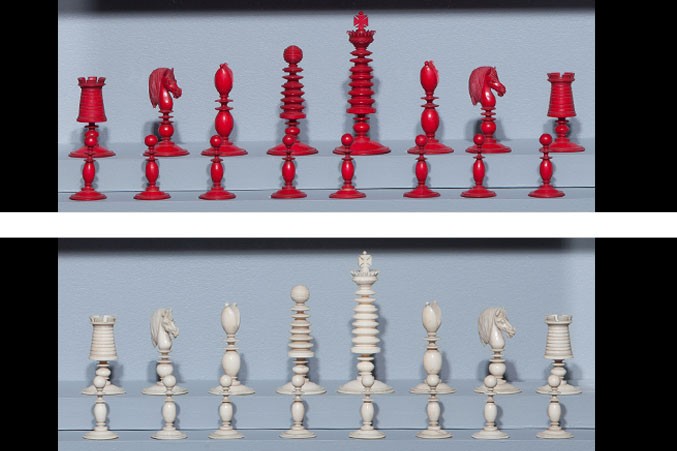

Selenus Type Ivory Set, 1790

King Size: 3 3/4 in.

Ivory

Unlike other sets of this type, this Selenus style set includes representational sculptures of a royal court. Selenus chess sets are characterized by their tall, elegant, and slender forms and tiered decoration. They are named for their resemblance to a set in an illustration by Jacob van de Hayden in Das Schach oder Konig-Spiel, a well-known book about chess written in 1616 by Gustavus Selenus.

Germany

German Erbach Ivory Figural Set, 1885

King Size: 4 1/3 in.

Ivory

Originally polychromed, traces of the set’s original coloring are evident in the hints of pink, blue and green along the indentations of the chessmen. Differing costume colors and pedestal colors marked the opposing armies of this chess set.

Germany

German 18th-Century Board-Box, 18th Century

16 1/4 x 16 1/4 x 3 1/4 in.

Wood

Edel Style Ivory Set, 19th Century

King Size: 3 1/4 in.

Ivory

Exquisitely and finely carved tiered decoration characterizes this magnificent set. It is made in the style of Michael Edel, a designer and creator of chess sets who lived in Munich, Germany, in the 19th century. The rooks, which resemble the bell towers of churches, are characteristic of his work. Sets like these were turned and carved in multiple parts, then assembled by a craftsman. The box for this set contains not only a chessboard, but also, when opened, a backgammon board. Chess and backgammon have a long association, as recognizable forms of each game emerged from neighboring civilizations—chess from India and backgammon from Persia—around the 6th century.

Works Featured in the Exhibition: French

France

Alsatian Ivory Jester Set, 1850

King Size: 4 in.

Ivory

Blending distinctive attributes of French and German styles of chess sets, this set contains both figural and non-figural representations of a royal court. An artisan in Alsace, a region with both French and German heritage, created the set. The king and queen have tiered and petaled layers of ornamentation, which are characteristic of Selenus style sets, while the double-headed knights are included in some German sets. However, the gruesome fools, which take the place of the bishops, are commonly featured in sets created in Dieppe, France.

France

Dieppe Green and White Ivory Set, 1850

King Size: 3 1/2 in.

Ivory

Chess sets created by the master carvers of Dieppe, France, were sought-after souvenirs among British tourists who visited the coastal town. This set features the theme of European military forces attacking those of Africa, a popular subject among the tourists and artists in Dieppe. This set substitutes grimacing fous, or fools, for the bishops. Though the production of ivory souvenirs in Dieppe decreased after the French Revolution, it was revived after Napoleon bought ivory products there.

France

Dieppe Ivory Set, 1785

King Size: 3 1/2 in.

Elephant ivory and walrus ivory

Typical of Dieppe sets, here an African army battles a European army. The fous on the European side wear simple costumes, but have menacing, devious facial expressions. On the African side, the fous also have horns.

France

Dieppe Ivory Blue and White Set, 1800

King Size: 3 1/4 in.

Ivory

The master carvers of Dieppe, France, imported ivory from Africa in order to create sets like these. Unusual for this style of set, this one features pieces stained with a blue pigment. The hobby horse knights are characteristic of late 18th-century Dieppe sets, and even appear in a similar set that was owned by Thomas Jefferson.

France

French Figural Régence Set, 1900

King Size: 4 in.

Ivory

This French Figural Régence Set blends attributes of the Régence style of set, a popular type of playing set in 18th century France, with figural representation. The Régence style was named after the Café de la Régence in Paris, where many skilled players and intellectuals congregated. The white queen and king wear fashionable garments associated with wealthy individuals of the 15th and 16th centuries.

France

French Bust Ivory Fou Set, 19th Century

King Size: 3 9/10 in.

Ivory

The unusual depiction of the faces on the white and black sides differentiates this set from many others of the same type. The white king’s pointed beard, broad jawline, and rounded nose give the face an unusual level of personality and character. Fou in the set’s title refers to the fool that takes the place of the bishop.

France

French Dieppe White and Black Set, 1810

King Size: 2 3/4 in.

Ivory

Scowling kings, queens, and bishops with furrowed eyebrows add a sense of menace to this Dieppe set. Here, the artisan played with the sculptural possibilities of ivory. The white crowns are hollow with narrow beaded strips stretching from the topmost cross to the base of the crown. The textural details of the costumes as well as the exaggerated facial features show a distinctive approach to chessmen representation.

France

Dieppe Europeans vs. Moors Ivory Set, 1800

King Size: 3 1/2 in.

Ivory

In the 17th century, Dieppe, a French city located on the English Channel, became a center of ivory working. Artisans there created chess sets from African ivory imported from the country of Senegal. Often, these sets had humorous aspects, caricaturing contemporary figures. The theme of Africans versus Europeans among was very popular among westerners during the 19th century, when many European nations expanded their territory on other continents.

France

French vs Turks Ivory Set, 1810

King Size: 4 1/10 in.

Ivory

Depicting a French king and queen wearing medieval costumes adorned with fleur de lis, this set likely embodies the theme of the Crusades. Here, the French bishops appear as pious friars. The set has an elaborate gilt and tooled case (not on display) that is in the style of those created in the Palais Royal, arcaded luxury stores located in 19th-century Paris.

Works Featured in the Exhibition: Chinese/Asian

China

Chinese Green and White Ivory Set, 1830

King Size: 3 3/4 in.

Ivory

Though created in 19th-century China, the white king, queen, bishops, and knights are modeled in the same style as English ceramic chess pieces of the 18th century. The hybrid rooks contain representations of both European style rooks and an elephant, which represented the piece in some Asian sets. During the 19th century, the trade routes that had been established between European nations and those in Asia led to cultural exchange, which in turn increased demand and appreciation for Asian art in Europe.

China

Macao Set, 1850

King Size: 4 in.

Ivory

As in other sets manufactured in China for trade with western nations, this set shows a European king battling an Asian leader. The Union Jack, or national flag of the United Kingdom, tops the rooks. The set is named for Macao, a onetime Portuguese colony and center for trade, which is now a Special Administrative Region of China. Macao sets often feature figural depictions of the faces of leaders along with horses and turrets, displayed atop pedestals with elaborate floral decoration. Though in these sets one side is usually colored red or green, this one was not stained during its manufacture.

Myanmar (Burma)

Burmese Figural Ivory Set, 19th Century

King Size: 3 1/2 in.

Ivory

This rare, Burmese-style chess set represents two armies, led by the seated kings and their great generals. They are followed by military figures atop elephants and horses, while tiered temples represent the rooks. The seated pawns are compactly posed figures bearing weapons and shields.

China

Burmese Style Ivory Set, 1810

King Size: 4 1/2 in.

Ivory

Once thought to be a style of set created in Burma, which today is known as Myanmar, research has proven that this ornate type of set was actually produced in China. Like the Macao set, also on view in this case, this ornately carved set features heavily ornamented, tall pieces better suited for display than play. The sets both also feature figural representations of rulers, horses, and towers atop bases with elaborate floral decoration.

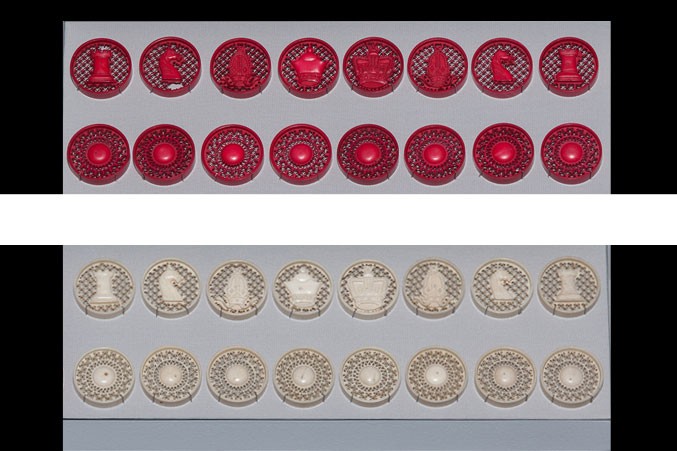

China

Chinese Ivory Filigree Disc Set, 1860

King Size: 1 1/2 in. (Diameter)

Ivory

Silhouetted representations of European-style chess pieces appear before intricately carved filigree backgrounds on the pieces in this disc set. The carving attests to the skill of the set’s creator. Though artists also created disc sets with solid backgrounds, examples with delicate latticework like this are more desirable to collectors.

China

Cantonese King George Ivory Set, 1860

King Size: 5 in.

Ivory

The finest chess sets in China were manufactured in Canton, where this elegant set was created. The British introduced Europeanized chess to China in the late 18th century, when they established trade networks in the country. Chinese ivory artists soon began producing gorgeous chess sets both for export and visiting tourists. Made for the British market, this set shows British forces battling the Chinese. The figures in sets like these often represent specific historical leaders, namely King George III and Queen Charlotte.

Works Featured in the Exhibition: Russian, Muslim, and Italian

Russia

Kholmogory Set, 1800

King Size: 3 1/4 in.

Walrus ivory

Ships with unfurled sails as rooks are characteristic of sets produced in the Russian city of Kholmogory. Located on the White Sea, on a trade route between the Russian interior and Europe, the city became known for fine decorative goods in the 17th and 18th centuries. The artisans of Kholmogory often created sets with the theme of a Russian army warring against a Muslim enemy, here both represented in white. As in some Indian sets, this one features a military advisor in the place of a queen.

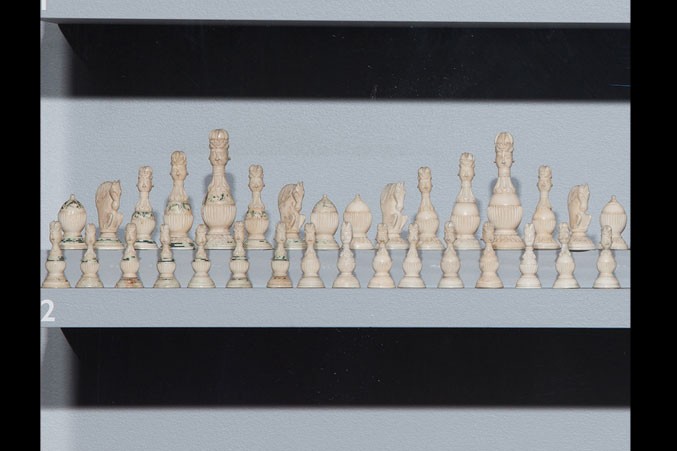

Russia

Kholmogory Mammoth Ivory Set, 1780

King Size: 2 3/4 in.

Mammoth ivory

A much rarer style of Kholmogory set than the full-length figural pieces also on display in this exhibition, this set features kings, queens, bishops, and pawns with carved faces atop egg-shaped bases with decorative grooves.

Russia

Kholmogory “Little Faces” Mammoth Ivory Set, 1790

King Size: 3 in.

Mammoth ivory

This set is made from mammoth ivory, an abundant resource in northern Russia at the time of its creation. Bone and ivory carving were rich folk traditions in the region, partially due to the ready availability of walrus and mammoth ivory. This folk art received special attention in the mid-16th century, when Kholmogory’s master carvers began to work in Moscow’s Armory Palace, where weapons and decorative objects for the tsars were created and housed. As these master artisans received the patronage of the court, folk traditions blended with those of royal art.

Middle East

Islamic Red and White Ivory Set, 1800

King Size: 1 1/2 in.

Ivory

The abstract forms of these pieces evoke the soaring spires, minarets, and massive domes sometimes found in Islamic architecture. The avoidance of figural representation conforms to the belief held by some Muslims that artists should avoid making figurative artwork, as creating forms was the work of Allah. The pieces are differentiated by size and mass rather than through figurative carving.

North Africa

North African Marine Ivory and Wood Muslim Chess Set, 19th Century

King Size: 2 in.

Ivory and wood

Brown and white pieces made of wood and marine ivory add contrasting textures, finishes, and weight to this simple playing set. Marine ivory can refer to materials from whales, walruses, or narwhals. The tops of each set are decorated with floral forms, while the knights and queens have finials in contrasting colors.

India

Indian Ivory Pattern Chess Set, 1870

King Size: 2 in.

Ivory

This lovely Islamic set features a simple but distinctive style of ivory decoration, which has been found on objects from India and the Islamic world dating as far back as the 8th century CE. Incised concentric circles and bands are filled with green and red pigment. This set is larger, chunkier, and of a higher quality than many others of the same type.

India

Indian Muslim Polychrome Set, 1780

King Size: 1 3/4 in.

Ivory

Though simple in form, with kings and queens resembling spools, this set glows due to its brilliant colors. It is decorated with gilding in quatrefoil patterns on the stems and tops of the bases, as well as chevron patterns around the bottoms. Islamic art often incorporates geometric patterning like this in the place of figural representation.

Italy

Italian Red and White Ivory Figural Set, 19th Century

King Size: 3 in.

Ivory

Somber kings and queens wear patterned turbans topped by crowns, sometimes an attribute of Islamic leaders in Italian art. Their serious faces are balanced by that of the knight, a horse with an expression of surprise. Italy’s position on the Mediterranean Sea led it to have contact with the Islamic world through both trade and war.

C. Gazza

Italy

Ivory Bust Chess Set on Metal Pedestals, 1880

King Size: 5 in.

Ivory and metal

Blending ivory and gilded metal decoration, this gorgeous chess set is an example of chryselephantine, or sculpture incorporating both media. Though an ancient art form, chryselephantine sculpture was popular among artists of the Art Nouveau movement, which flourished in Europe and the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This movement embraced art that looked back to a romanticized version of preindustrial times.

South Europe

South European Ivory Inlaid Hardwood Chess Board-Box, 16th/17th Century

13 x 10 1/2 in.

Hardwood and ivory

Italy

Italian 18th-Century Set, 1790

King Size: 3 in.

Ivory

As chess reached new cultures in Asia, Europe, and Africa after its creation in India, its rules evolved, as did the forms and figures associated with each of the pieces. Artists and artisans from various cultures created their own distinctive styles of chess sets, and even within single countries, diverse styles often proliferated. During the mid-19th century, the rise of organized competitive chess and chess clubs highlighted a need for more standardized sets.

United States

Holly and Teak Board, 21st Century

25 1/2 x 25 1/2 in.

Wood

Italy

Italian Figural Ivory Set, 1900

King Size: 3 7/8 in.

Ivory

The ancient conflicts between the Greek and Achaemenid (First Persian) empires form the theme for this militaristic set. Each culture is brought to life through rooks that resemble their famous architecture—for the Persian side, this includes lamassu, or winged bulls with the faces of men, that adorned monuments in cities like Babylon and Persepolis. Additionally, each has pieces that speak to the cultures of each empire, including philosophers as bishops for the Greek side and musicians on each side with native instruments. The set appears on a simple and classic 21st-century board.

Works Featured in the Exhibition: John Company

India

John Company Ivory Set, 1840

King Size: 4 in.

Ivory

In this John Company Set, leaders stationed in howdahs, or carriages atop the backs of elephants, lead two armies to war. This is called a composite set because it contains associated pieces with slightly different bases from more than one set, though each was created during the same era and possibly even the same place. Though the bishops, queens, and black king have slightly different bases, the quality of the carving may indicate that these could have been made by the same creators.

India

John Company Tiger Hunt Set, 1820

King Size: 5 3/4 in.

Ivory

Though John Company sets often included representations of the army of the British East India Company battling Indian military forces, this set has a more rare theme, that of the tiger hunt. This subject may have held special appeal to audiences in Europe, where an interest in Asian cultures flourished during the 18th and 19th centuries. Now referred to as Orientalism, this literary and artistic movement resulted in artists, poets, and writers creating accounts of life both real and imagined, in the “Far East.”

India

John Company Baby Elephant Set, 1850

King Size: 4 1/4 in.

Ivory

Like the tiger hunt set also displayed in this case, this set is a unique variation on the theme usually presented in John Company Sets. Here baby elephants with raised trunks represent the bishops, taking the place of the camels that more commonly represent the piece in this style of set. The elephant, used as a working animal in India, was the subject of the most striking pieces in John Company sets, but it was also a source of the ivory used to create these decorative trade objects.

India

Indian Ivory and Ebony Chessboard, 19th Century

20 x 20 in.

Ivory and ebony John Company Set, 1830

King Size: 5 in.

Ivory

East India “John” Company chess sets derive their title from the nickname of the East India Company, which operated in India until 1874. Some of the “John” sets depicted the army of the East India Company combatting an Indian army. A carving center staffed by master artisans was established in Berhampur, India, where the British had built a military barracks. There, beautiful chess sets like this one were produced to meet the demand of British citizens living in India, as well as visiting tourists and foreign dignitaries. The set is paired with an Indian board that includes the iconography of Indian chess sets on the white squares on the back rank.

Works Featured in the Exhibition: Indian Figural

India

Anglo-Indian Polychrome Ivory Set, 1850

King Size: 3 in.

Ivory

The polychromed, or multi-colored jewel toned, surfaces of this set are largely intact and original to the pieces. The curvature of the figures indicates that they are from smaller, curved pieces of tusk, making it a less expensive set than some of the larger and more delicately carved Indian sets on view in this exhibition.

India

Central Provinces Ivory Set, mid-19th Century

King Size: 2 1/2 in.

Ivory

Carved in a naive but charming style, this set features snarling lions as bishops. Once thought to have been made in the Central Provinces of India, the set is now believed to have been produced in Vizagapatam, a district in the Madras Presidency of British India. Stylistic features, including the large-headed lions as bishops, support this attribution.

India

Rajasthan Ivory Set, 1880

King Size: 4 1/2 in.

Ivory

Named for Rajasthan, a state in Northwest India, this style of set has been created in India for centuries. Images of this type of set appear in Thomas Hyde’s 1694 publication De Ludis Orientalibus, or The Book of Oriental Games. Here, the two armies are depicted in red and green. Leaders in canopies atop elephants command the armies, which count individualized pawns carrying swords, spears, and musical instruments among their numbers.

India

Indian Figural Ivory Set with Seated Kings, c. 1920

King Size: 5 1/2 in.

Ivory

Enthroned kings, seated below decorative parasols, are the highlights of this heavily ornamented set. This set has features characteristic of 20th-century Indian sets, including the angular carving style and the pawns, which depict warriors riding on horseback. The bishops, knights, rooks, and pawns bear soaring banners, which along with the rolling landscapes below them, lend a sense of dynamic action to this set.

India

Indian Ivory Sandalwood Board, 1810

18 3/8 x 18 in.

Ivory and wood

Indian Figural Ivory Set, 1850

King Size: 3 1/16 in.

Ivory

This set is distinguished by its unusual rooks, which feature tented arches topped by onion shaped domes, reminiscent of architectural styles in the country in which it was made. Here, an army is led by a king with a military advisor bearing a scimitar, or curved sword, at his side. The set is shown with an ivory and sandalwood board. Its board features engraved ivory decoration filled with lac. Artisans in Vizagapatam used this technique to create objects like sewing boxes, tea caddies, document boxes, and game sets for export to Great Britain.

Works Featured in the Exhibition: Indian Non-Figural

India

Berhampore Kashmir Style Ivory Chess Set, 19th Century

King Size: 5 in.

Ivory

Whimsical architectural and botanical forms inspired the creators of this elaborate ornamental chess set. Once believed to have been created in Kashmir, the northwestern region of South Asia, research by expert Michael Mark has shown that the area did not have major ivory markets during the period when pieces like this were produced. Sets in this style were made almost exclusively for export to Great Britain.

India

Indian Ivory Skirt Set, 1850

King Size: 3 3/4 in.

Ivory

The skirted decoration on this red and white ornamental set is a simplified version of the more elaborate carving on the Kashmiri sets also on display in this case.

India

Vizagapatam Ivory Flame Chess Set, 1830

King Size: 5 in.

Ivory

In this set, tall pawns are topped by buds soon to burst into bloom, while flames curl above the king and queen. It was created in Vizagapatam, a district in the Madras Presidency of British India, which was well-known for ivory decorative arts. The Union Jack flags atop the rooks are common features of chess sets made for trade.

India

Kashmiri Ivory Chess Set, 1810

King Size: 6 1/2 in.

Ivory

Like the other Kashmiri set on display in this case, this set blends abstract and representational elements. On the back rank, the king and queen are embellished architectural forms, while the pawns are full-length figural representations of soldiers bearing weapons.

India

Samuel Pepys Style Ivory Set, 1820

King Size: 5 1/4 in.

Ivory

British and Indian stylistic influences are mixed in this set, which has tiered leafy decorations on its bases and finials resembling those of European-style chess pieces. The towers on the rooks, as well as the shapes of the bishops, display the taste of the British consumers of the sets, while the beautiful pierced and botanical decorations reflect the artistic traditions of India. Though impractical for use as a regular playing set, this gorgeous object communicated the taste and wealth of its owner.

India

Indian Sadeli-work Chessboard, 1850

17 x 17 in.

Wood, ivory, and metal

Samuel Pepys Black and White Ivory Set, 1870

King Size: 6 1/4 in.

Ivory

This Samuel Pepys set is named not for its maker, but for a famous man once believed, but now disproven, to have been given a set of this type by King James II of England. Made in India, it features a hybrid of British and Indian stylistic influences. The towers on the rooks, as well as the shapes of the bishops, communicate the taste of the British consumers of the sets, while the carved decorations reflect the artistic traditions of India. The tall, slender forms of the sets made them impractical for playing, as they could be easily knocked over during a game. The set is paired with a Sadeli Indian board. Sadeli is a type of micro mosaic with repeating geometric patterns. Examples of Sadeli work date back to the 16th century.

India

Vizagapatam Ivory and Rosewood Board, c. 1800

16 1/4 x 18 1/8 in.

Ivory and rosewood

Indian Ivory Set with Prancing Knights, 1825

King Size: 5 1/4 in.

Ivory

Created in Vizagapatam, an ivory carving center and hub for trade from India to Great Britain, this board displays elaborate floral motifs. It is shown with a set that similarly takes inspiration from nature, with petaled tiers of ornamentation and naturalistic prancing horses as knights. The set also incorporates political references—the queen is topped by the “Prince of Wales’s feathers,” ostrich feathers that when grouped, serve as a symbol of the British monarchy.

India

Anglo-Indian Chess Board, 1875

18 x 18 in.

Wood and ivory

Indian Ivory Playing Chess Set, 19th Century

King Size: 4 1/4 in.

Ivory

Though made during the second half of the 19th century, this set includes knights created in a much earlier style. The horses, with their arched necks and downcast faces, resemble those found in Indian sets produced for the British export market during the late 18th century. The other parts of the set are in a style commonly produced during the mid-to-latter 19th century. This set is paired with an elaborately carved board, featuring beasts and human figures amongst a foliate background.

India

Vizagapatam Miniature Chess Table and Set, 1830

King Size: 1 1/2 in.

Ivory, wood, tortoiseshell

After British tourism expanded in India, artists there began to produce miniatures that appealed to this new market of consumers. The table has intricate filigree decoration surrounding its border, with small panels depicting Hindu religious figures. The tiny set that accompanies the table is based upon simple British playing sets, though its small size lends it additional delicacy.

Works Featured in the Exhibition: English Calvert

England

English Ivory Figural Set, 1830

King Size: 4 in.

Ivory

Unlike the other sets in this case, this set contains figural representations of a royal court. The queen wears a long robe with an empire waist and long elbow-length gloves. The rook is represented by an elephant with a tower topped by battlements. In the crenellations, or gaps, tiny cannons are positioned for defense.

England

Calvert-Style Lund Set, 1840

King Size: 3 1/2 in.

Ivory

Created by London chess set maker, William Lund, this set is made in the style of another manufacturer, John Calvert. Lund’s shop was located across the street from Calvert’s workshop, which had large storefront windows for the display of his products. Viewing Calvert’s sets on a daily basis may have influenced the production of this set that borrows from Calvert’s style.

England

Washington Ivory Set with Calvert-Stamped Rooks, late 18th Century

King Size: 3 1/2 in.

Ivory

The stamp of John Calvert, one of the top producers of chess sets during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, appears on the tops of the rooks in this set. It is made in a popular 18th-century style called the “Washington set,” and serves as visual evidence of the evolution of Calvert’s designs. Though he did not originate this style of set, he created a unique style of knight to accompany it. He would later go on to create a more distinctive style of set that would influence those produced by many of his London contemporaries.

England

Calvert Style Ivory Set, 1820

King Size: 3 1/2 in.

Ivory

Though this style of set was later imitated by other chess set manufacturers, including Lund and Merrifield, John Calvert originated it. The heavy rooks and lively knights, represented by horses with bulging eyes, are typical of his sets. The Jaques company, one of the most famous manufacturers of playing sets, would later include a representation of this style in its pattern book.

England

Calvert Set with Box and Dorothy Calvert Flier, 1820

King Size: 4 1/4 in.

Ivory

John Calvert was a member of the Master of Worshipful Company of Turners, a trade guild set up during the medieval era to protect the interest of artist members who were skilled at turning and shaping wooden objects on a lathe. After his 1822 death, his wife Dorothy Calvert then took over and kept his company running. She then sold the stock in 1835 and later died in 1840.

England

Calvert Stamped Ivory Set, 1820

King Size: 2 5/8 in.

Ivory

England

Regency Chessboard (detail), c. 1815

21 x 21 in.

Wood

The white rooks in this elegant playing set bear the stamp of the Calvert workshop, which was established in 1791. The simple playing set is displayed with an elaborately embellished penwork board. Penwork was a fashionable form of decoration in Great Britain during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Created by drawing images over a layer of lacquer or paint then applying a layer of shellac, penwork decoration imitated the effect of more expensive decorative arts. Artisans sometimes incorporated original designs, but other times included images from popular culture. Here the squares of the chessboard alternate between figural representations and those of picturesque landscapes.

Works Featured in the Exhibition: English Lund

England

Victorian Ornamental Ivory Set, 1850

King Size: 4 1/2 in.

Ivory

This set, as well as the English ornamental playing set also on view in this case, represent decorative variations of the Staunton style chess set. Named for Howard Staunton, the sets became the standard for tournament play during the mid-19th century and are still used today. Though adorned with decorative surface textures, these sets maintain the essential qualities of the Staunton set’s forms.

England

English Ornamental Playing Set, 1880

King Size: 4 1/4 in.

Ivory

England

Fisher Red and White Set, 1840

King Size: 4 1/2 in.

Ivory

William Lund, a London manufacturer of ivory chess sets as well as small decorative and utilitarian objects, likely created this chess set, which features his distinctive style of knights and pedestaled rooks. Though he later sold chess sets through his own business, William Lund also created sets for another London manufacturer, Samuel Fisher.

Thomas Lund

England

Antique Ivory Chess Set, 1840

King Size: 3 1/2 in.

Ivory

Like the Jaques and Calvert companies, Thomas Lund, and later his son William, manufactured beautiful playing sets during the 19th century. Thomas Lund first appears in city directories in 1804 working as a cutler, or maker of knives and other instruments. He also made chess sets. After his 1845 death, his son William took over management of the family’s second shop, which Thomas had formerly run.

England

Lund Style Unstamped Set with Custom Box, 1850

King Size: 3 in.

Box Size: 6 3/4 x 5 3/4 x 4 1/4 in.

Ivory

A simple box with knight-shaped latches accompanies this Lund playing set. On the interior of the box’s lid is a list of the relative values of the chess pieces.

Works Featured in the Exhibition: English Miscellaneous

Great Britain

British Northern Upright Ivory Set, 1860

King Size: 4 in.

Ivory

Northern Upright is a regional style of set that was popular in Great Britain during the 19th century. It is a predecessor to the Staunton set, the most famous style of playing set. Artisans often used cochineal dye, which was derived from an insect of the same name, to produce the brilliant red color in playing sets like this one.

England

Antique Hand-painted Chessboard, late 19th Century

21 x 21 in.

Paper

Northern Upright Tall Ivory Set, c. 1830

King Size: 3 5/8 in.

Ivory

By the mid-1800s, as chess was becoming more organized and competitive, there was a call for pieces to become distinct and uniform. The Northern Upright style is considered a predecessor to the Staunton set, which eventually became the standard for all official chess competitions worldwide. The forms of the pieces sit atop slender columns, but the set’s clean lines and simple style bear a strong resemblance to the now-famous Staunton design. The set is paired with a colorful 19th-century hand-painted chessboard.

England

Jaques Set—Lord Vernon with Box, 1855

King Size: 4 1/2 in. Box Size: 8 1/4 x 6 x 4 7/8 in.

Ivory

This trophy or gift set is named for the man who presented it, a member of the British Parliament named Lord Vernon. An inscription on the base of the box that accompanied this set indicated that he presented at his residence, Sudbury Hall, in October 1857. John Jaques and Son, Ltd., of London, a leading manufacturer of chess equipment during the 19th century, created the set.

England

Washington Set, 1775

King Size: 4 in.

Ivory

Though this was a popular type of set in England, it has become known as a “Washington set” because American President George Washington owned one of this style. These sets were also well-liked by the British aristocracy because they featured red and white pieces, colors associated with St. George, the patron saint of England.

England

A.B. Barrett & Sons

Northern Upright Set with Box, 1880

King Size: 4 in.

Box Size: 7 x 4 1/4 x 5 1/4 in.

Ivory

Though artists often used ivory to create elaborate ornamental chess sets, as in this example, they also used it to produce upscale versions of playing sets that were commonly made from wood. A.B. Barrett & Sons, a London-based manufacturer, created this set in the Northern Upright pattern.

England

Hastilow Barleycorn Ivory and Bone Set with Card, 1860

King Size: 7 1/2 in.

Ivory and bone

The leafy decorations around the barrels on the centers of the kings and queens in this style of set lend it the name of barleycorn. Though this type of chess set originated in England, it soon spread to the United States and Germany. This is the only set directly attributable to Charles Hastilow, a masterful carver of ivory. One of his sets was included in the 1862 International Exhibition, a world’s fair held in London, England, which highlighted examples of arts, technology, and industry from around the globe.

England

Merrifield Black and White Ivory Set and Casket, c. 1840

King Size: 3 1/2 in.

Ivory

The casket, or box, for this chess set bears gorgeous inlaid floral decoration, showing the attention to detail paid to every aspect of this luxurious playing set. Unlike many of George Merrifield’s chess sets, the box had not been stamped with his mark. Merrifield worked as an ivory turner in London from 1818 to 1852. In 1807, he apprenticed under John Calvert, another renowned ivory turner and chess set craftsman.

Works Featured in the Exhibition: North America

United States/Alaska

Alaskan Inuit Chessboard, 1900

25 1/2 x 25 1/2 in.

Fur

Inuit Walrus Ivory Set, c. 1940

King Size: 3 1/8 in.

Walrus ivory

Creatures of the arctic, including bears, whales, eagles, seals, and walrus take center stage in this charming mid-20th-century chess set. As in Kholmogory, Russia, there were long traditions of bone and ivory carving in Alaska that artists adapted to creating trade items after contact with outside cultures. These included scrimshaw and small decorative items, and by the late 19th and early 20th centuries incorporated chess sets. This set embraces the unique qualities of walrus ivory, which often gains a yellow and white marbled quality with age, to depict the two opposing sides. This set is paired with an Inuit chessboard made of strips of woven fur.

Works Featured in the Exhibition: Central Displays

France

French Chess Table, 1800

21 1/4 x 38 1/2 x 28 1/2 in.

Wood, ivory, and tortoiseshell

Battle of Waterloo Figural Ivory Chess Set, 1840

King Size: 4 in.

Ivory

Many of the pieces in this polychromed chess set are based upon historical figures from the French Emperor Napoleon’s final conflict, the Battle of Waterloo. On the French side, Napoleon is king and the Empress Marie Louise is queen, the bishops are Marshals Michel Ney and Jean-de-Dieu Soult, and the rooks are columns topped with the French Imperial Eagle, the standard carried by Napoleon’s forces into battle. On the British side, King George III and Queen Charlotte lead a force that includes Major-General Lord Edward Somerset (with one arm) and Colonel John Cameron as bishops. The set is paired with a gilded French gaming table.

Spain

Spanish Gaming Table, c 1860

32 3/4 x 18 x 30 1/2 in.

Wood and metal

England

British Chess Company Club-Size Ivory Set and Large Stamped Board, 1900

King Size: 5 in., Board: 21 x 21 in.

Ivory and wood

Established in 1890, the British Chess Company only operated for about fifteen years, but in that time had a lasting impact. In addition to being a leading producer of chess equipment, it also collaborated with players to compile a regulated set of rules known initially as the British Chess Code and later, across the Atlantic, as the American Chess Code. The company’s efforts represented the first major attempt to standardize the rules of chess for a broad audience. The set is paired with a gaming table sold by Olivella Hermanos y Cuspinera of Barcelona, a store known for distributing Chinese and Japanese export art during the late 19th century.

India

Indian Brass Inlaid Hardwood Chess Table, 1880

11 x 10 3/4 x 25 1/2 in.

Hardwood and brass

Indian Islamic Ivory Set, 19th Century

King Size: 2 1/2 in.

Ivory

Gilded floral decoration adorns the simple abstract forms of this Indian Islamic Ivory chess set. It complements the scrolling vine and stylized floral patterns on the surface of the Indian brass inlaid hardwood chess table.

France

Rosewood and Tortoiseshell Chess Table, 1880

31 1/2 x 31 1/2 x 29 in.

Rosewood and tortoiseshell

French Field of the Cloth of Gold Figural Ivory Set, 19th Century

King size: 5.25 in. Ivory

The theme of this set is the meeting of the English King Henry VIII and the French King Francis I at the Field of the Cloth of Gold. The two kings, along with their retinues, met near Calais, France, in 1520 for a gathering intended to increase the bonds of friendship between the two nations. The French and the English tried to outdo each other with extravagant shows of wealth. Many of the tents and much of the clothing worn by the guests was made of cloth of gold, an expensive fabric composed of gold and silk, which lent its name to the diplomatic meeting. The two queens, Catherine of Aragon and Claude of France, bear resemblance to the historical figures upon whom they are based.

England

Lecture Podium-Chessboard, 1880

18 x 15 1/2 x 29 3/4 in.

Wood

The unique form of this lecture podium and chess board may indicate that it was a special commission by a patron.

England

George Bullock Chess Table, 1815

16 1/2 x 25 7/8 x 29 1/2 in.

Wood

James Leuchars Ivory Set, 1810

King Size: 4 in.

Ivory

James Leuchars, a London manufacturer of chess equipment sold this ornamented playing set. After his death, his widow, Lucy, took over the business. Eventually, her son William would run the firm, which would become the first retailer of Staunton pattern sets in December 1849. The board with which it is paired was made by George Bullock, a well-known furniture maker from the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

China

Chinese Green White Ivory Chess Set in Lacquered Cabinet, 1850

King Size: 5 1/2 in. 15 1/4 x 26 x 40 in.

Ivory and lacquered wood

This beautiful lacquered cabinet was produced for the Chinese export trade. Created primarily as an object for display, the set features a white king and queen modeled upon the British monarch George III and his wife, Queen Charlotte. The green side represents Chinese leaders. The set is accompanied by a folding game board.

Marble Specimen Chess Table, 1880

20 3/4 in. diameter 27 3/4 in. tall

Marble

England

Hastilow-Style Set, 1840

King Size: 4 1/2 in.

Ivory

Though this is a playing set, it features beaded decoration. The rooks are towers topped by waving flags and the kings have crowns topped by Maltese crosses. The multicolored examples of marble specimens lend a special beauty to the surface of this chess table.

Press

09/08/2020: US Chess — One Move at a Time September Edition: Jon Crumiller (podcast)

11/01/2015: 50 Moves — Coverage of the 2015 Sinquefield Cup by Ian Rogers (download)

09/28/2015: Nicki’s Central West End Guide — Exquisite Chess Sets on view at World Chess Hall of Fame

09/07/2015: The Chess Drum — Reflections of 2015 Sinquefield Cup

08/28/2015: West End Word — “Mischief Makes A Move” World Chess HOF Brings Dadaist Exhibition to Central West End

06/17/2015: Saint Louis Public Radio — On Chess: Appreciating the art of ivory chess sets

Encore! Exhibition Press Release