October 10, 2019 - March 22, 2020

A Beautiful Game

A Beautiful Game both showcases lovely artifacts from the World Chess Hall of Fame collection—chess-inspired beauty products, photographs, posters, and advertisements—and illustrates how the sophistication and brilliance of the game have been celebrated and revered in chess and popular culture. The exhibition also highlights new, interactive artwork by chess champion and author Jennifer Shahade as well as Pinned! fashion designer Audra Noyes.

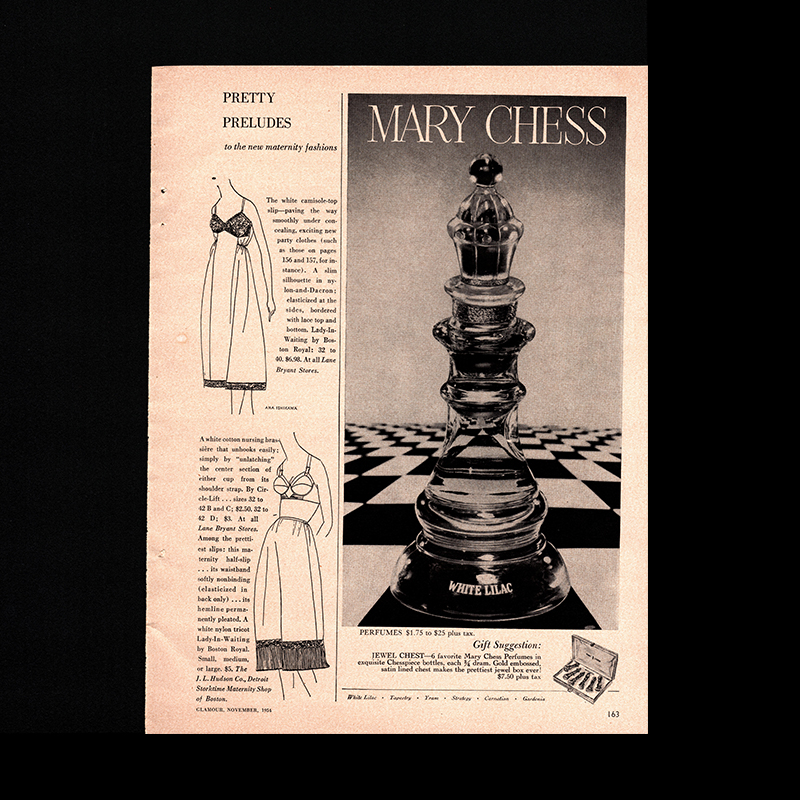

Chess is often described as a beautiful game, and its association with intelligence and strategy has made it an appealing subject for advertisements for a wide range of products, from automobiles to lipstick. A Beautiful Game highlights many of the chess-inspired beauty and fashion artifacts in the collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) as well as illustrating how beauty is celebrated in the game of chess. Delicate Mary Chess perfume bottles from the WCHOF collection provided inspiration for staging A Beautiful Game. The Mary Chess company was named for its founder, Mary Grace Chess Robinson, who was born in Kentucky and had first created a name for herself through creating artificial flowers. In the 1930s, she began to create floral-scented perfumes and lotions in her kitchen. In 1939, when Mary Chess was choosing the bottles for her line, she gained inspiration from an image of an antique amber chess set once owned by members of the Hohenzollern dynasty. A pattern from a 17th-century Venetian chessboard adorned the wrapping paper for her packaging. Her logo, a queen piece, appeared on a variety of products from perfume to dusting powder, though in a 1942 interview she stated that neither she nor the other executives at the company played chess.

Photo by Carmody Creative

The Mary Chess items are only a small part of a much larger collection of artifacts related to chess, fashion, and beauty that we have amassed since the WCHOFmoved from Miami to Saint Louis in 2011. Among them are products by Lipstick Queen, whose founder Poppy King visited the Chess Forum, a shop and game parlor in New York, to learn about the game while developing her chess-themed collection. Following Bobby Fischer’s victory in the 1972 World Chess Championship. Avon created a line of aftershaves and colognes in chess piece-shaped bottles that collectors could assemble into a full chess set. There are also numerous advertisements incorporating chess themes from companies as diverse as Chanel, Revlon, and Maidenform, and the reigning World Chess Champion Magnus Carlsen has appeared in advertisements for the Dutch clothing company G-Star RAW. These advertisements illustrate how companies use the game of chess to evoke a variety of themes including intelligence, elegance, refinement, glamour, tradition, strategy, and power.

Chess Piece Perfume Set in Spice Box

After 1957

King Size: 3 in.

Box: 4 ½ x 3 ⁷⁄₈ x 4 in.

Glass, metal, cardboard,

plastic, and perfume

www.milton-lloyd.com UK’s favourite fragrance company

Roman Bath Oil Perfume

1940

www.milton-lloyd.com UK’s favourite fragrance company

Fragonard Oval Cream

Perfume Locket

After 1963

1 ½ x 1 ¾ in. dia.

Metal, milk glass, and cream perfume

www.milton-lloyd.com UK’s favourite fragrance company

Toilet Water Sampler

c. 1932-1942

Bottle: 2 ⁷⁄₁₆ x ¾ in. dia.

Box: 2 ¾ x 9 ¹⁄₈ x ¹⁵⁄₁₆ in.

Glass, plastic, cardboard, and perfume

www.milton-lloyd.com UK’s favourite fragrance company

Rainbow Quartet Perfume Bottles

c. 1945-1960s

Bottle: 3 x ¹⁵⁄₁₆ in. dia.

Box: 5 ¹¹⁄₁₆ x 4 ⁷⁄₁₆ x 1 ³⁄₁₆ in.

Glass, metal, and cardboard

www.milton-lloyd.com UK’s favourite fragrance company

Strategy Dusting Powder

After 1942

Powder: 2 x 5 in. dia.

Box: 5 ⁵⁄₈ x 5 ⁵⁄₈ x 2 ⁷⁄₈ in.

Plastic, cardboard, and dusting powder

www.milton-lloyd.com UK’s favourite fragrance company

The Golden Court Set of Perfumes

c. 1945-1960s

King size: 3 in.

Box: 8 ½ x 3 ½ x 3 ⁵⁄₈ in.

Glass, metal, and cardboard

www.milton-lloyd.com UK’s favourite fragrance company

White Lilac Essence Spray

After 1932

Bottle: 8 x 2 ¼ in. dia.

Box: 9 ¹⁄₈ x 3 ½ x 2 ⁵⁄₈ in.

Glass, metal, cardboard,

satin, and perfume

www.milton-lloyd.com UK’s favourite fragrance company

The WCHOF is dedicated not only to exploring the history of the game but also how it is viewed and presented in popular culture. This mission leads us to organize exhibitions like A Beautiful Game and past shows exploring the intersections of chess and fashion including PINNED! A Designer Chess Challenge (October 6, 2017 – March 25, 2018). The latter exhibition paired designers from the Saint Louis Fashion Incubator (Audra Danielle Noyes, Charles Smith II, Agnes Hamerlik, Allison Mitchell, Emily Brady Koplar, and Reuben Reuel) with chess players (GM Maurice Ashley, GM Christian Chrilia, GM Alejandro Ramirez, GM Fabiano Caruana, WGM Jennifer Shahade, and IM Nazi Paikidze Barnes) in a challenge to create an ensemble for a contemporary chess player. Noyes, who was paired with GM Maurice Ashley, won the challenge and a $10,000 scholarship. Noyes sees her design process as similar to the experience of playing chess: she inserts the unexpected into designs that draw from the guidelines of classical tailoring much like a chess player finds spontaneity within the structure of the game. A stunning piece from Noyes’ Autumn/Winter 2018 collection, which is inspired by the power of the queen appears in A Beautiful Game.

Photo by Carmody Creative

In addition to showcasing beauty and fashion-related artifacts, A Beautiful Game includes a display related to concepts of beauty in chess. People often debate whether chess is an art, game, or sport. Chess brilliancy prizes, which were once commonly offered at tournaments, honor individuals who played games of great originality and often featuring stunning sacrifices. In 1876, Henry Bird won the first-ever brilliancy prize for his game against James Mason in the Clipper Free Centennial Tournament. During the remainder of the nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth century, many tournaments offered brilliancy prizes. They were sometimes offered throughout the history of the U.S. and U.S. Women’s Chess Championships. One memorable brilliancy prize winning game fought on American soil was Bobby Fischer’s famous victory over Donald Byrne in the 1956 Lessing J. Rosenwald Tournament. Later labeled the “Game of the Century,” it featured a dramatic queen sacrifice. Today, brilliancy prizes are typically awarded in tournaments.

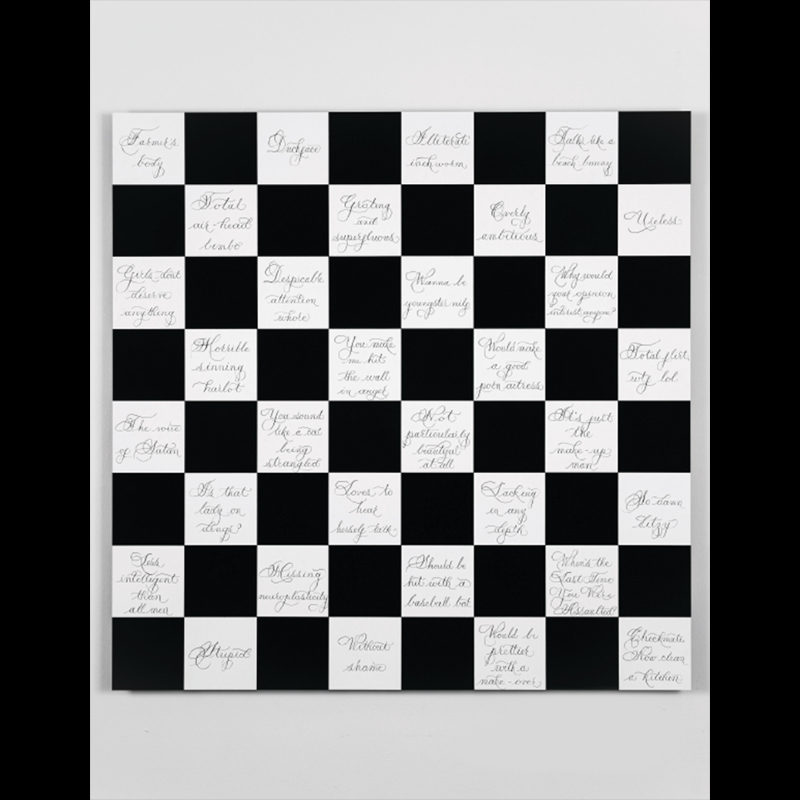

A Beautiful Game also marks the debut of a new artwork by two-time U.S. Women’s Chess Champion and Program Director at US Chess Women Jennifer Shahade and filmmaker Daniel Meirom. Not Particularly Beautiful is inspired by a misogynistic chessboard covered in insults directed at women, which was printed in French poet Gratien du Pont’s 1534 book Les Controverses des Sexes Masculin et Féminin (The Controversies of the Male and Female Sexes). Shahade and Meirom debuted the first version of the work at the Boston Sculptors Gallery in October 2018. That version of Not Particularly Beautiful was an oversized chessboard featuring calligraphy of insults directed at Shahade and other female chess players on the white squares. On the black squares, female chess players, students, and artists were invited to share memorable insults they had endured: however some instead flipped the challenge and offered encouragement to other women.

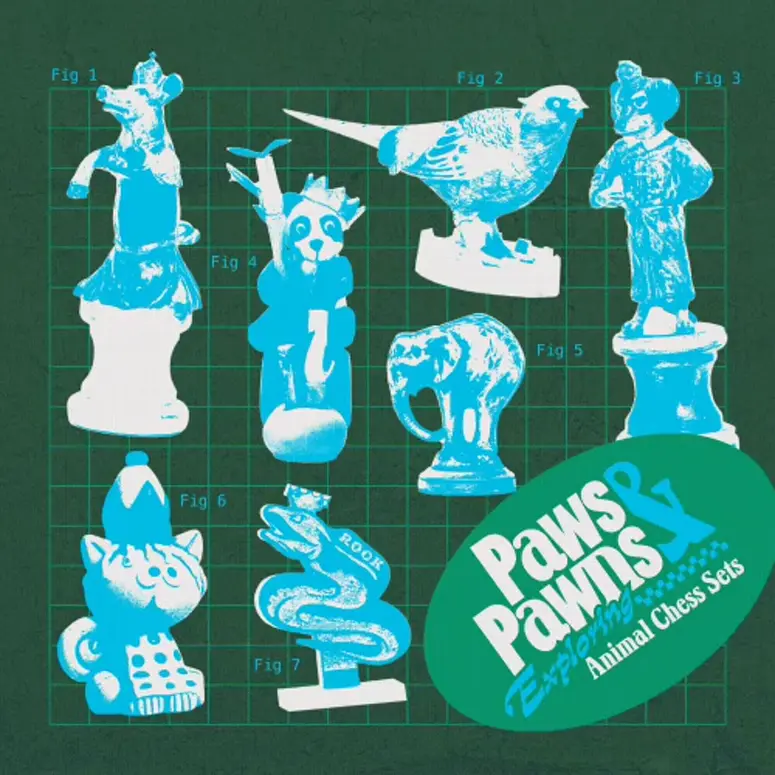

A Beautiful Game contains artifacts that approach the intersections among chess, beauty, and fashion in numerous ways: Yuko Suga’s Image Re: In Glass encourages self reflection through a chess set atop a vanity, Avon’s cologne bottle chess set produced after Bobby Fischer’s victory in the 1972 World Chess Championship, and prints and books related to beautiful chess games. We hope that you will enjoy the pieces on view, from Karen Walker’s contemporary designs inspired by World Chess Hall of Fame inductee Sonja Graf and U.S. Women’s Chess Champion Lisa Lane, to numerous advertisements blending the strategy of chess with the world of beauty and fashion.

National Association of Avon Clubs Chessboard

1976

22 x 22 in.

Wood and plastic

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Silver and Copper Enamel Chess Set and Board

Early 20th century

Lipstick Chess

2017

Lipstick tube: 2 ⅝ in.

Box: 2 ¾ x ¾ x ¾ in.

Matte lipstick and cardboard box

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Image Re: In Glass

2017

King Size: 4 in.

Board: 19 x 17 ¼ x 21 ¼ in.

Glass, wood, plastic, and acrylic

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Virginia Leith Models with Mary Chess Perfume Bottles

1957

9 ½ x 7 in.

Photograph

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

December 1967

10 ⅛ x 7 ⅞ in.

Paper

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

1920

13 ½ x 10 ¼ in.

Paper

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

1947

13 x 9 ½ in.

Paper

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

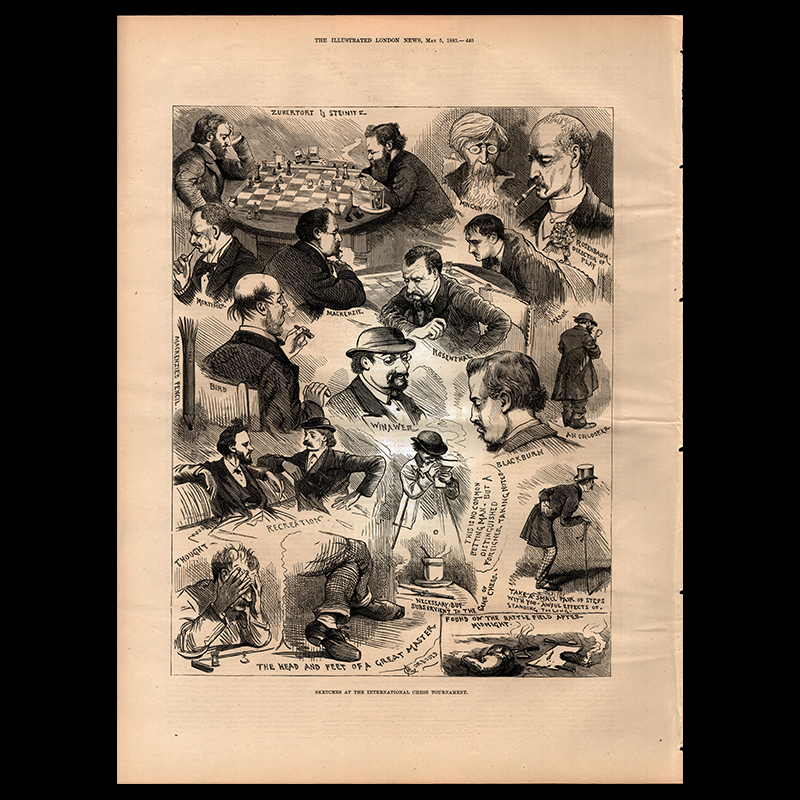

“Sketches at the International

Chess Tournament”

1883

15 ⅞ x 12 ¾ in.

Paper

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

IM John Donaldson

Compared to other arts or sports chess is an easy game to learn, but a difficult one to master. Just how difficult? Malcolm Gladwell, in his best-selling book Outliers: the Story of Success (2008), postulates that “the key to success in any field is, to a large extent, a matter of practicing a specific task for a total of around 10,000 hours.” However, while that might get you to the level of national master (2200), it is nowhere near the top of the ladder as the international master (2400) and grandmaster (2500) titles are well above this yet far from becoming champion (2800+). Gladwell’s judgment is not new. Forty years ago, in a paper in American Scientist, Herbert Simon and William Chase drew one of the most famous conclusions in the study of expertise:

“There are no instant experts in chess—certainly no instant masters or grandmasters. There appears not to be on record any case (including Bobby Fischer) where a person reached grandmaster level with less than about a decade’s intense preoccupation with the game. We would estimate, very roughly, that a master has spent perhaps 10,000 to 50,000 hours staring at chess positions…”

The level of national master is the point at which a player becomes capable of playing a mistake-free game from beginning to end, but this is more of a technical than artistic achievement. To go beyond this and play a game which is both sound and filled with imagination, where standard rules are cast aside, requires something much more. So rare and special are these games that they are referred to as brilliancy prize games.

Since chess was first played, fans of the game have put the highest value on games which feature shocking and surprising moves, ones that raise the pulse from 60 beats per minute to 160 in a matter of seconds. These mind over matter battles, in which the normal pace is transcended, ensure the winner and the loser instant immortality, their names destined to be remembered for as long as chess is played.

The first brilliancy prize in a tournament was awarded to the Englishman Henry Bird for his victory over James Mason of Ireland. Bird sacrificed his queen for a rock, obtaining long-term compensation, but no immediate win. The game took place in New York in 1876 when Ulysses S. Grant was president but is still played over and reviewed by chess players today.

One of the first games to be universally recognized as a true brilliancy was played between the champions of the United States and Russia in Breslau, Germany, in 1912. There Frank Marshall defeated Stepan Levitsky in a smoke-filled tournament room crowded with onlookers, finishing the game by playing a spectacular move that allowed his queen to be captured three different ways, but which offered Levitsky no defense. Legend has it that the spectators were so caught up in the moment that they showered the board with gold pieces to honor Marshall for his fantastic feat of imagination. More skeptical souls have speculated that this exciting game generated a lot of betting action and that the incident at its conclusion was just the losers paying up.

This historic encounter later inspired a doppelganger brilliancy prize won by Nicholas Rossolimo against Paul Reissmann at the U.S. Open in San Juan Puerto Rico, in 1967. Rossolimo, in the spirit of Marshall, moved his queen to a seemingly impossible square where it could be captured by two different pawns. Marshall and Rossolimo, New Yorkers who both managed chess clubs (the Marshall Chess Club and Rossolimo’s Chess Studio), were kindred souls who shared both an artistic temperament for the game and a romantic and adventurous outlook on life. Marshall was known to walk even the most dangerous streets of New York, comforted by his cane which doubled as a concealed gun, while Rossolimo drove a taxi, practiced judo, recorded folk albums, and was an expert linguist. Both were expert chess alchemists who could make their pieces come to life.

Chess is often referred to as part sport, part science, and part art, and it is the latter category where the brilliancy prize fits. While art and sport don’t always mix, in chess they sometimes do, and it should come as no surprise that world champions have won more than their fair share of brilliancy prizes. International Master Jeremy Silman, in an article written for chess.com, calculated that Mikhail Tal, the “Wizard of Riga” is the all-time brilliancy prize holder with 15 prizes followed by Gary Kasparov with 12 and Anatoly Karpov with 10. Bobby Fischer, who admittedly had a much shorter career, won only four, but if one single battle by a world champion is to be remembered it might be Bobby Fischer’s victory over Donald Byrne in the 1956 Rosenwald tournament, where the 13-year-old sacrificed his queen in what Hans Kmoch dubbed the “Game of the Century.” If that doesn’t do it there is always Bobby’s win over Donald’s brother Robert in the 1963/64 U.S. Championship. Rumor has it that the two grandmasters in the commentary room thought that Bobby was lost just before he played his final move which caused Bryne’s resignation.

Photo by Carmody Creative

The late International Master Danny Kopec, in his introduction to Winning the Won Game: Lessons from the Albert Brilliancy Prize (2003), writes about how what constitutes a brilliancy prize has changed over time. The importance of the underlying soundness of the game is now deemed essential. Flawed play, imaginative though it might be, no longer passes muster. He also quotes the Russian professor A. Smirnov, writing in 1925, whose definition of brilliance in chess is still relevant today:

“Brilliance in chess is a complex concept, as complex as the nature of chess itself, combining features of art and science. Its main indication is practical expediency, with which it not only accidentally coincides, but is also intrinsically linked. Scientific thought appears brilliant to us, when it appears distinctly, apparently unexpectedly, and most important fruitfully. It’s precisely this that constitutes intrinsic brilliance in chess…”

No matter what the formal definition of brilliancy in chess is, chess players know it when they see it. As long as the game is played these inspired games and the players who created them will be remembered.

Chess History and Reminiscences

1893

8 ⅜ x 11 in.

Hardcover book

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Brilliancy Prize Trophy from the 1914 Western Chess Association Championship

1914

8 ⅞ x 6 in. dia.

Metal

Collection of Dwight Weaver, Memphis Chess Club Historian

Jacqueline Piatigorsky Calderon Brilliancy Prize-U.S. Women’s National

Chess Championship

1955

13 ⅛ x 3 ⅛ in. dia

Metal

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

Jacqueline Piatigorsky Hollywood Chess Group “B” Championship Brilliancy Prize

1951

7 ¼ x 2 ¾ in. dia.

Metal and marble

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

Jacqueline Piatigorsky’s U.S. Women’s Championship Brilliancy Prize

1955

2 13/16 x 6 x 4 7/16 in.

Metal and bakelite

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

Chess Brilliancy 250 Historic Games from the Masters

2002

9 9/16 x 6 7/16 in.

Paperback book

Collection of World Chess Hall of Fame

Not Particularly Beautiful

Daniel and I are very proud to present Not Particularly Beautiful at the World Chess Hall of Fame. When the chess queen became the most powerful piece on the chessboard over five centuries ago, the new game was at first mocked as the “mad-women’s” chess game—our piece shows how there is still resistance to female empowerment, especially from anonymous “trolls.” The so-called mad woman’s chess game became the great game we now play, and I hope Not Particularly Beautiful will inspire women and men to persist through criticism and backlash, as that negativity often precedes a change for the better.

Daniel Meirom and Jennifer Shahade

Not Particularly Beautiful

2019

40 x 40 in.

Scratchboard, clay board, and ink

Courtesy of Jennifer Shahade

“Her Voice Makes Me Envy the Deaf.”

The title of our piece is a YouTube insult levied at me when commenting on a chess tournament, “She is not particularly beautiful at all.” The white squares of our piece were crafted from online comments about female chess champions. All these could have been replaced by silence. A silence that trolls clamor for, both literally and in violent metaphor.

“You Sound Like a Dying Cat Being Strangled.”

Not Particularly Beautiful is an homage to the women through history who have endured criticism and backlash as they found new power, inspired by the “mad woman” chess’s queen. The chess queen was once the weakest piece on the board, only able to move one square diagonally. Games were long and tedious, as it was much harder to checkmate without the chief executioner.

“Is that Lady on Drugs?”

Around 1500, as powerful queens reigned in Europe, the piece rose to the potent powerhouse of the board she is today. This new, faster, and better game that we still play over five centuries later was initially derided as the “mad-woman’s chess game.”

“Lacking in Any Depth”

Not Particularly Beautiful was inspired by a 1534 chess engraving by French writer and critic Gratien du Pont, a piece that I originally read about in Marilyn Yalom’s Birth of the Chess Queen (2001). It was later re-introduced to me by the artist Donna Dodson, when she invited Daniel Meirom and me to show work in her 2018 exhibit Match of the Matriarchs.

In protest of the new chess game, Gratien created a chessboard with an insult for the queen on each of the sixty-four squares. Some squares, translated as “True She-Devil” and “Very Negligent,” are eerily reminiscent of the same insults trolls use to belittle female and non-binary brilliance and ambition today.

“Missing Neuroplasticity”

The invention of the printing press standardized the new mad queen rules of chess, where regional differences had often prevailed previously. Calligrapher Emily Reichlin lovingly penned the squares of Not Particularly Beautiful in her signature script named “The Grace” after Grace Kelly. Of the font, Reichlin said, “It’s an elegant, feminine script that I felt was a fitting juxtaposition to the ugliness and misogyny of the content.” You can zone in on a capital “M” so stunning that it erases the pain of a cruel word.

“Overly Ambitious”

Online chess culture has improved in the few years since I compiled these mean slurs. Active, often paid moderation, along with tactics like shadow-banning (muting an abusive user without their knowledge) helps flush out trolls. Allyship, male feminists, and intersectionalism spreads infectious positivity.

In our first edition of Not Particularly Beautiful, we invited exhibition attendees to fill in the black squares with chalk, starting with sculptor Donna Dodson, who wrote “Ugly” in capital letters on a center square.

“Without Shame”

One woman asked me as we handed out chalk, could she write something nice? Of course, I replied- there were no restrictions. After she wrote “The Future is Female,” many of the remaining squares filled up with positive counters, like “Your Voice Deserves to be Heard” and “You are Worthy.” This mirrors online communities, where both compliments and name-calling spread like wildfire, making initial declarations incredibly important.

“Less Intelligent then All Men”

The Saint Louis Chess Club is ramping up efforts to grow girls and women in the game, from the top women’s tournament the Cairns’ Cup, weekly Ladies’ Knight classes, and a partnership with US Chess to bring more females into the game via the US Chess Women Initiative. The World Chess Hall of Fame has presented exhibitions featuring female artists exploring chess themes and women chess champions. Its exhibit, A Beautiful Game, debuts the second version of Not Particularly Beautiful.

“Loves to Hear Herself Talk”

On US Chess’s Ladies Knight podcast interview, popular streamer Alexandra Botez explained to me her low tolerance for trolls as she built a community of 50,000 Twitch followers, while another famous chess player and personality Anna Rudolf wrote: “The best response to them is to keep going and keep growing. Your own success is the best middle finger.”

Daniel Meirom and Jennifer Shahade

Not Particularly Beautiful

2019

40 x 40 in.

Scratchboard, clay board, and ink

Courtesy of Jennifer Shahade

“Would Look Better with a Makeover”

Not Particularly Beautiful is part of a growing trend I’ve seen to reclaim and tackle negative comments head on. The old advice “not to feed the trolls” or to “ignore the haters” can be sound in some cases but condescending and insufficient in others. Many contemporary artists, musicians, and writers have incorporated negative feedback from fans into creative work in very literal ways.

In Lifting the Sweetness, weightlifter and performance artist Kleida Spiro (with whom we collaborated with on a chess and weightlifting performance, The Battle of the Beasts) cleaned and jerked a barbell loaded with melons as male audience members shouted things that she frequently heard at the gym from men, like “Nice Melons” or “Time to Clean Up.”

In The Bully Pulpit, photographer Haley Morris-Cafiero staged elaborate scenes, imagining the lives and appearances of online attackers as they pelted vicious words at her. In Bad Blood, Australian artist Casey Jenkins ratcheted up the shock level by converting online insults levied against her earlier work Casting Off My Womb into wool canvases dyed with her own blood.

“When’s the Last Time You’ve Been Assaulted?”

Even ardent feminists may critique this genre of art as attention seeking and whiney. I’ve stopped myself when reposting a mean comment on Twitter, knowing that friends and fans will eloquently defend me, but also using the tactic sparingly because it’s so easy, with guaranteed victory.

But an aggressive approach toward cruelty and bigotry is also spiriting. Gratien du Pont initially wished for his misogynistic chess board to be anonymous, but he was exposed. Like du Pont, the message to casual haters is clear. Comments veering from rude to evil won’t always evaporate as an aberration, a temporary and therefore acceptable cruelty. They may just end up viral on Twitter, in a comedian’s punchline, the New York Times, or the wall of a museum.

For more information view our exhibition brochure here!

Funding for this exhibition provided by the Missouri Arts Council, a state agency.

Press

02/13/2020: St. Louis Public Radio — On Chess: Brilliancy In Chess

10/31/2019: Explore St. Louis — A Beautiful Game

10/17/2019: St. Louis Public Radio — On Chess: Not Particularly Beautiful

10/14/2019: St. Louis Post Dispatch — World Chess Hall of Fame Exhibits Celebrate Best of Chess, Fashion and Beauty

10/10/2019: Ladue News — Fall 2019 Exhibitions Opening Reception

9/24/2019: Press Release — World Chess Hall of Fame Exhibits Celebrate Best of Chess, Fashion and Beauty