March 6, 2019 - October 27, 2019

US Chess: 80 Years

US Chess: 80 Years—Promoting the Royal Game in America celebrates the official governing body of American chess and its many accomplishments since its 1939 founding. The exhibition uses audio, video, photographs, and never-before-exhibited artifacts which illustrate US Chess’s mission to empower people, enrich lives, and enhance communities through chess.

US Chess: Empowering People One Move at a Time

US Chess formed 80 years ago out of the merger of two predecessor organizations: The American Chess Federation and the National Chess Federation. The newly combined entity, now named the United States of America Chess Federation (and currently known as US Chess), primarily promoted tournament play throughout the country. More importantly, the U.S. Chess Championship, the U.S. Open, and the U.S. Olympiad team now fell under a single organizational roof and served about 1,000 members.

There have been many important milestones since 1939 as US Chess grew and evolved. Bobby Fischer’s quest for the World Championship in the 1960s and 1970s, the growth of scholastic chess, the broadening of the US Chess mission beyond the organization’s singular focus of rated play, and most recently, Fabiano Caruana’s challenge to Magnus Carlsen for the World Championship.

Fabiano Caruana during Round 4 of the 2018 U.S. Chess Championships, 2018

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Along the way, US Chess has learned much about itself and what a powerful tool chess is. As we now look towards the century mark and approach 100,000 members, we embrace our heritage while looking for new ways to excel. As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit with an educational mission, we are branching out to explore new program areas described below.

Inaugural Cairns Cup Opening Ceremony, 2019

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

First, we recognize the potential of chess as a learning tool. We can recite many stories about the role of chess in early childhood development as it relates to providing building blocks for future academic success in areas such as mathematics. Chess teaches one to think critically, plan every move, and understand that actions have consequences. Through an objective ratings system, among other measures of success, chess provides a framework for people to realize their potential outside of a classroom where different types of excellence are rewarded. The resultant skills place students on a path for not just educational achievements but also later successes within their career and life.

Second, we accept chess as a tool for the social and emotional development of young people. Chess is a game where sportsmanship is core to the game’s culture. Winning, losing, and drawing teach people how to act graciously no matter the situation.

Third, we increasingly see interest in chess as a rehabilitative tool. Whether as an intervention for a stroke victim, an individual with dementia, or a person with a traumatic brain injury, we actively seek to partner with other organizations who are working to improve outcomes for individuals with cognitive impairment.

Fourth, US Chess is a place for anyone—regardless of gender, national origin, age, or any special circumstances. We enthusiastically work to promote the game to under-represented groups within our existing community, including women and girls, at-risk youth, and seniors. As a boundless, universal game, chess truly is a uniting enterprise for all.

Carol Meyer, US Chess Executive Director

US Chess: 80 Years—Promoting the Royal Game in America

US Chess: 80 Years—Promoting the Royal Game in America celebrates both the 80th anniversary of the US Chess Federation (US Chess) and a new golden era for chess in the United States. The World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) and Saint Louis Chess Club (STLCC) have been privileged to witness this transformation and are proud to partner with US Chess on this exhibition. Since 1939, US Chess has built and sustained a community of American chess lovers, from its early efforts to bring the benefits of the game to those injured during World War II via the Chess for the Wounded program to its current efforts to bring more girls and women to the game through the US Women’s Chess Initiative. Through its mission, US Chess empowers people, enriches lives, and enhances communities through chess.

US Chess: 80 Years is a natural fit for our institution—the first location of the WCHOF, then known as the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, was established in the basement of the US Chess Federation’s former headquarters in New Windsor, NY, in 1988. A highlight of our collection is the first artifact acquired by the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame and displayed at that initial location—the silver set presented to Paul Morphy for his victory in the 1857 American Chess Congress. Since 2009, the STLCC has hosted the U.S. and U.S. Women’s Chess Championships, putting the WCHOF in the unique position to collect important artifacts related to the history of American chess as it happens in our hometown. Every year we hold the inductions for the newest inductees to the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame at the opening ceremony for the U.S. and U.S. Women’s Chess Championships, honoring legends of American chess in front of the game’s best players. We see the benefits that chess brings to diverse audiences firsthand—the STLCC has reached over 40,000 students through its scholastic programs and draws chess enthusiasts from around the country during the championships as well as the Sinquefield Cup, the strongest tournament ever held on American soil.

GM Maurice Ashley Poses with GM Gata Kamsky at their Induction to the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, 2016

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

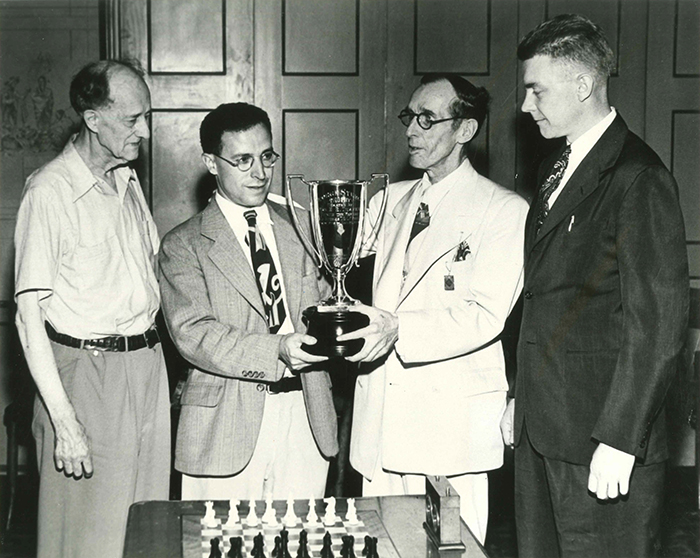

The WCHOF’s collection is rich in artifacts related to the history of American chess. From the first yearbook produced by the newly-formed US Chess Federation to photographs of American players competing at the highest levels of international chess, the artifacts showcase how the organization has evolved over its 80-year history. During its first decade, which coincided with the outbreak of World War II, the organization experienced a period of quiet growth. In August 1940, the organization’s membership was estimated at just 1,000 members. However, they built the organizational structure that still exists today and created the first issues of Chess Life—then published as a newspaper. Though World War II interrupted the World Chess Championship cycles, the organization continued to organize the U.S. and U.S. Women’s Chess Championships, which included many of the figures who earned the most wins in the competitions’ histories: Gisela Gresser, Mona May Karff, and Samuel Reshevsky. The organization also held its first U.S. Open Chess Championships. The George Sturgis trophy, named for US Chess’s first president and engraved with the names of the earliest winners, is a highlight of the collection of the WCHOF and is featured in this exhibition.

In the 1950s and 1960s, American chess experienced many rapid changes. A group of young stars, including Larry Evans, William Lombardy, and Bobby Fischer, began competing in tournaments. Fischer’s accomplishments—becoming (at that time) the youngest player to achieve the title of grandmaster and winning the U.S. Chess Championship—would attract not only the attention of chess enthusiasts but also the general public. Fischer appeared on I’ve Got a Secret in 1958, prior to competing in the Portoroz Interzonal Tournament. Additionally, U.S. Women’s Chess Champion Lisa Lane appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated on August 7, 1961. During the same period, US Chess, led by President Jerry Spann, launched a membership campaign that more than doubled its membership (2,100 to 4,579) from the years of 1957 to 1960. Materials from Spann’s archive, including photos from American tournaments are being exhibited for the first time in US Chess: 80 Years. The Spann Collection, which is owned by US Chess includes a large number of archival materials related to his activities on the national and international stage, promises to be a great resource for researchers interested in the early history of US Chess.

The 1960s also saw the staging of one of the highest-rated tournaments ever held in the United States—the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, which featured competitors including future world chess championship rivals Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer. Fischer’s rise to the top of international chess in the late 1960s and early 1970s created the “Fischer boom,” inspiring people around the country to take up the game. In 1972, the year that he clinched the world chess championship title, membership in US Chess was 30,844. In just one year, that total nearly doubled, rising to 59,250 members. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, new national competitions, including the U.S. Junior Chess Championship, the National High School Chess Championship, the National Junior High Chess Championship, and the National Elementary (K-6) Championship, were created, providing an arena for young players to compete and build their skills.

Jacqueline and Gregor Piatigorsky at the First Piatigorsky Cup, 1963

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame, gift of the family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky

The decade also witnessed the rise of a new generation of American-born women who would challenge Gisela Gresser and Mona May Karff’s 30-year dominance of U.S. women’s chess. Diane Savereide and Rachel Crotto, along with future US Chess President Ruth Haring, won the country’s top women’s chess competitions and represented the country on the global stage. In the 1979, Alicante, Spain, Interzonal, Diane Savereide had the best performance of any American female player from the 1930s to the early 1990s. Other members of the Fischer boom, including Joel Benjamin, Larry Christiansen, John Fedorowicz, Nick de Firmian, and Yasser Seirawan represented the United States in international competition in the 1980s. Many top players from around the world immigrated to the United States in the 1980s and 1990s, including former Women’s World Chess Champion Candidate Elena Donaldson-Akhmilovskaya and Boris Gulko.

US Chess: 80 Years celebrates many of the milestones of the 2000s as well. In the 2004 Calvía, Spain, Women’s Chess Olympiad, a team that included future seven-time U.S. Women’s Chess Champion Irina Krush took team silver for the first time in the event. In 2016, the U.S. Olympiad team, which included Fabiano Caruana, Hikaru Nakamura, Wesley So, Sam Shankland, and Ray Robson took team gold for the first time since 1976. The first U.S. Junior Girls Chess Championship was held in 2014 and has since become one of the national chess championships held annually in Saint Louis. In 2019, the U.S. Senior Chess Championship will also be held in Saint Louis for the first time. More than illustrating trends in US Chess, we hope to begin to collect the stories of individual players, writers, and organizers through this exhibition. US Chess: 80 Years debuts a new video featuring interviews with many of the commentators and journalists who enliven our coverage of Saint Louis Chess tournaments, including US Chess Women’s Program Director, Woman Grandmaster Jennifer Shahade. The exhibition also premieres material from a new collaboration with the Chess Journalists of America (CJA). The project includes interviews between members of the CJA and figures from American chess. This brochure also contains remembrances from past editors and writers for Chess Life. A special installation in US Chess: 80 Years invites visitors to share their own memories of participating in US Chess tournaments and what chess means to them, allowing us to both preserve important parts of chess history and show why the game is important.

Carissa Yip and Jennifer Yu Shake Hands before Round 9 of the 2018 Girls’ Junior Chess Championship, July 21, 2018

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

In 2018, the Saint Louis Chess Campus celebrated the tenth anniversary of the Saint Louis Chess Club and a resurgence of chess in the United States sparked by the “Sinquefield Effect”—the efforts of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield to support chess in the United States. The same year, an American—Fabiano Caruana—contested the World Chess Championship title in a unified World Chess Championship match for the first time since 1972. The 2019 U.S. Chess Championship will feature five super grandmasters—Fabiano Caruana, Wesley So, Hikaru Nakamura, Sam Shankland, and Leinier Dominguez—making it not only the top event in American chess, but also a world-class tournament. With rising young talent and US Chess membership at its highest in its history, we are proud to celebrate the storied past and bright future of US Chess in 2019.

Children Playing Chess at the 10th Anniversary Celebration of the Saint Louis Chess Club, 2018

Collection of the WCHOF

Emily Allred, Associate Curator, World Chess Hall of Fame

Special thanks to International Master John Donaldson, whose research for the World Chess Hall of Fame was of great assistance in the creation of this essay.

US Chess and Women

Playing chess at a high level requires confidence, focus, and drive. My favorite part of the game is losing yourself in thought, and thought resembling music in those moments.

So many of chess’s benefits are of particular value to girls and women. In a world of rising distractions, chess encourages deep, slow thought removed from devices and immediate comparisons. Players check ratings immediately after a tournament on the US Chess website, but during a game, they get lost in knight forks and checkmating nets. In a February 18, 2019, interview with Forbes, I explained how chess requires young people to learn to calibrate their self-confidence, “switching” from wise self-criticism while preparing to self-assurance while in combat.

In my new role as US Chess Women’s Program Director, I will bring the key benefits of chess to more women and girls, while being conscience of challenges that women in various situations face. Women of color, transgender women, women with disabilities, and women with small children add so much valuable perspective to our subculture and we can’t afford to leave anyone out. “Chess is like life to me,” as a young fellow Philadelphian says in Jenny Schweitzer’s video “Girls in Chess,” featured in this show.

Ladies’ Knight Class Taught by the Saint Louis Chess Club, 2019

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

At US Chess, the numbers of girls and women playing are rising, but the change is gradual. We are up to about 15% participation, from about 10% a decade ago.

At the highest levels, there is also progress as our youngest female players are among the best players in the country. At eight years old, Rachael Li recently broke the record for the youngest female expert in our 80-year history. In an incredible example of synchronicity, another girl, Alice Lee, broke the record the same week. Also in 2018, Jessica Lauser became the first woman ever to win the U.S. Blind Championship.

Leadership at US Chess also mirrors the positive trends in our membership, as my longtime friend Jean Hoffman became the first female executive director in 2013 and was followed by another woman with great vision in 2017, Carol B. Meyer. Their tenures also overlapped with the leadership of former US Chess President Ruth Haring (1955-2018), who was a vocal advocate for women and girls in chess and would smile to see the continuing strides we are making in 2019. On February 1, 2019, girls were welcomed into Scouts BSA, allowing them to earn chess merit badges. The very first weekend possible, I helped lead a workshop at the Saint Louis Chess Club to award the first girls in history the chess merit badge. In my lesson, I showed them a beautiful checkmate executed by seven-time U.S. Women’s Champion Irina Krush. As Dr. Jeanne Sinquefield explained to me, scouting badges are not only about learning, but also about sharing knowledge. “I don’t know why,” one scout said as she showed another girl the stunning “epaulette” mate from the Krush victory, “but it’s just so beautiful.”

Scouts BSA Girls Merit Badge/Cairns Cup Community Day, February 3, 2019

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

The scouting workshop dovetailed perfectly with another historic event, the inaugural Cairns Cup (February 5-19), featuring ten of the top female players in the world, the strongest women’s event ever held on U.S. soil. Valentina Gunina of Russia won the event with a thrilling performance. In one game, she executed a checkmate that was so beautiful I created a version with fine chocolates in her honor. The gem was eerily similar to the checkmate I showed the scouts, with the final blow in both landing on the d7 square.

During the Cairns Cup, the Saint Louis Chess Club announced an incredible $100,000 donation to US Chess Women. I am honored to steward this gift on behalf of the federation. One of my primary goals is to spread more resources to local organizers and coaches who are already working to widen our base of female players and could use an extra push. I am passionate about improving the image of chess, and helping women and girls see their potential not only in the game, but in life. In my new US Chess podcast, “Ladies Knight,” inspired by a 2015 World Chess Hall of Fame show of the same name, I interview female chess champions, leaders, and visionaries. I asked one guest, Adia Onyango, about how she plays up to five games blindfolded. “When people ask if it’s hard, I just do it.”

Jennifer Shahade, US Chess Women’s Program Director

Early Predecessors of the US Chess Federation

The US Chess Federation has a distinguished pedigree, as the U.S. and Britain were the first nations in the world to form national chess associations. Furthermore, the first American Chess Association, formed in 1857, was along with baseball and cricket, one of the first national sports organizations in the United States. Despite our pioneering beginnings, it took many years for a permanent U.S. chess organization to become established. As strange as it seems today, for most of U.S. chess history American players saw little need for a national organization. Today, we would be lost without a rating system, a national magazine, regular championships sanctioned by an organization, standardized rules, a national scholastic program, and the additional roles US Chess has.

However, chess players in the 19th and early 20th centuries lived in a different world. They had no rating system, relying on vague concepts such as “first-class” player or “Rook player” in lieu of a standardized numerical system. There were comparatively few tournaments, even at the local level. There was no set method for determining a U.S champion, and there were many resulting problems regarding that title. Several national chess organizations in the U.S. were formed between 1857 and 1934, but all failed to thrive until the merger of two such organizations in 1939 to form the US Chess Federation (USCF), now named US Chess.

The first national chess association in the U.S., named the American Chess Association (ACA), was officially formed on October 19, 1857, at the First American Chess Congress in New York. Paul Morphy, who was soon to become one of the all-time great players, made the historic nomination of its first president, Colonel Charles D. Mead. Since Morphy was from Louisiana, his nomination of a New Yorker was an important gesture of national unity at a time of intense sectional divisiveness in the country.

The ACA decided to admit both individuals and clubs at dues “placed at so low a rate as to enable every chess-player to inscribe his name upon its book.” The ACA published one issue of The Bulletin of the American Chess Association, which outlined its plans to build chess interest in the U.S. and bring more cooperation among local clubs. The Bulletin published no other issues although such were intended. It remains possibly the first chess periodical to be officially published by any chess organization in the world. The ACA soon declared that it was “inexpedient” to hold its next Congress, projected to occur in 1860; and it became inactive. Nevertheless, it helped to inspire the formation of a Western Chess Association in Saint Louis on April 21, 1860, although that organization had no connection with the Western Chess Association formed in 1900.

Numerous other attempts were made to form national chess organizations over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Another American Chess Association was established in 1871 at the Second American Chess Congress, but gave little evidence of activity except for an abortive attempt to arrange a major tournament in 1873. Yet another American Chess Association was formed at the Third American Chess Congress in Chicago in 1874, but it soon dissolved. Undaunted by the failures of three predecessors, another national chess association was formed at the Fifth American Chess Congress in 1880. Hoping for more success, they adopted a new name: The Chess Association of the United States of America. They also had dues at the democratic level of $2. In spite of those changes, the association apparently did little.

Hope springs eternal, so on September 4, 1888, yet another national chess association was formed. This new organization was called the United States Chess Association (USCA). A significant feature of this new organization was the participation of state chess associations. (State associations were a new concept, dating only to 1885 though some regional associations had existed before then). In order to encourage the formation of new state associations, the USCA held a tournament of state champions alongside an open tournament. Max Judd and Jackson (J.W.) Showalter played in the state champions’ event, though their states did not have state associations and their “state champion” status was thus unofficial. Both had been claimants of the U.S. Championship, itself then unsystematized and controversial, so the USCA hoped a match between the winners of the open tournament and the state champions’ event would settle an official U.S. Championship. Although Showalter became the USCA Champion, it was not accepted as the overall U.S. Championship, which remained without a generally-accepted, systematized procedure.

The USCA did survive long enough to hold at least four tournaments at its annual congresses. However, when a new national organization was proposed in 1898, its organizers said that the USCA had not met since 1890, with a brief revival in 1893. With no viable national organization around, the American Chess Code (official rulebook) was published by the Manhattan Chess Club in 1897. On April 24, 1899, a new organization called The Chess Association of the United States was formed. It differed from its predecessors by emphasizing clubs rather than individuals as members, saying that “by placing control in the care of a council made up of delegates from all the chess clubs, it would so entwined with the direct interests of the local organizations that its work would be watched by all, and its life would become a part of theirs.” This attempt to better integrate the local and national levels fell flat, apparently, as World Champion Emanuel Lasker in 1904 was trying to “bring new life into the organization” by publishing its constitution in his magazine. However, Lasker also opined that “The wrecks of chess organizations that strew the beach of the ocean of time would seem to indicate that the chess-playing faculty is not accompanied by energy and continued effort that are necessary to success.” Fortunately, the success of US Chess since 1939 has proved Lasker’s pessimism wrong.

The Western Chess Association, founded in 1900 (one source gives 1890, though its list of tournaments begins with 1900) held its fifth annual championship in 1904 in Saint Louis in connection with the World’s Fair. That tournament allowed anyone regardless of residence to play. In 1906 the Western Chess Association called for a national gathering to form rules for an annual U.S. championship tournament. This call preceded by a month an effort by the Brooklyn Chess Club to create a new national association, a timing that caused some initial unpleasantness between the organizations. However, the Western Chess Association subsequently decided at its 1906 business meeting to remain regional, suggesting that other areas also form associations, while supporting efforts by others to create a national organization. The president of the Western Chess Association claimed that organization had 10,000 members in 1906. At its 1907 meeting, the Western Chess Association limited its “territory” to 16 states, plus Manitoba: the states were Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, Ohio, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. By 1916, membership was opened to all the U.S. The 1920 and 1923 tournaments of the Western Chess Association were held in Tennessee and San Francisco, respectively. The Western Chess Association consistently favored annual tournaments open to all players, a tradition that has remained over the decades in the U.S. Open Chess Championships. Other national chess organizations were formed in 1906 and 1921, but neither showed much activity.

Collection of Dwight Weaver, Memphis Chess Club Historian

In 1926 the National Chess Federation of the USA (NCF) was formed in Chicago. Maurice Kuhns, a president of the Western Chess Association, became the first NCF president. At last, permanence was achieved, as the NCF survived long enough to merge with another organization to form the US Chess Federation in 1939. The NCF accomplished several important goals that have been carried forward by today’s U.S. Chess. It affiliated with the newly-formed World Chess Federation, an affiliation that has been maintained by US Chess. The NCF gained control of the U.S. Championship, giving it an official, systematic status determined by regular official tournaments. The NCF established a scholastic chess program. Its effort to create a title system, however, was a non-starter until the numerical rating system came years later. The NCF had only $1 dues, but required a 3-person membership committee to “examine into the character and history of every applicant for membership”—hardly conducive to big growth in membership! The Western Chess Association soon became a chapter of the NCF, a move that some felt diminished the status of the Western organization and its annual national tournaments.

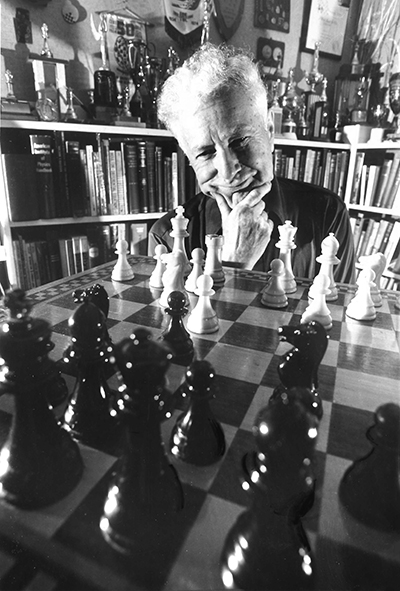

Perhaps due to this restrictive provision, and with some feeling that the NCF was too elitist, The American Chess Federation (ACF) was formed in 1934. The ACF was “a successor to the Western Chess Association,” according to Arpad Elo, its president and later a major pioneer in creating the worldwide rating system. Elo added in 1935: “The Western Chess Association was founded in 1900 at Excelsior Springs, Minn., and since that time has sponsored an unbroken line of annual tournaments. Originally these tournaments were intended to be merely regional in scope as the name of the organization indicated, but in 1916 the tournaments were opened to the chess players of the entire continent, and from that time on the outstanding players of North America competed to make the ‘Western’ a truly representative American tournament.” Elo listed a number of top players who competed in these events, including several who are now in the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame: Max Judd, J.W. Showalter, Edward Lasker, Isaac Kashdan, Samuel Reshevsky, and Reuben Fine. The ACF planned to disseminate a wider appreciation of the recreational benefits of chess, especially to “the younger generation.”

Arpad Elo, One of the Founders of the U.S. Chess Federation, 1980

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

© The Sentinel

In September 1939, the NCF and ACF agreed to merge into one organization, called the United States of America Chess Federation. The merger was legally formalized later that year. US Chess assumed the functions of both the NCF and ACF, including the NCF’s management of the U.S. Championship and its FIDE affiliation. The annual tournaments of the Western Chess Association and its successor, the ACF, became the U.S. Open Chess Championship held annually ever since by US Chess. In spite of this positive start, US Chess had only 299 members as of October 31, 1943. By 2003, the total membership reached 98,000. US Chess has become a major contributor to the international chess world in a number of ways, including popularizing Swiss system tournaments; issuing its own official rulebook; creating a major official chess periodical; and creating a numerical rating system that has been accepted worldwide.

The George Sturgis Trophy Being Presented to Anthony Santasiere, Winner of the 1945 Peoria, IL, U.S. Open Chess Championship, 1945

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

John McCrary, past US Chess President

The full version of this essay can be found here.

Out of the Desert

In the late 1970s, my family moved to a chess desert. Augusta, Georgia, may be a golf mecca as home of The Masters, but what it offers in birdies and bogies, it lacks in Bisguiers and Benjamins. Not that my chess life had been cosmopolitan before; since my father had taught me how to play during Fischer’s run to the world championship, dad was largely my only opponent.

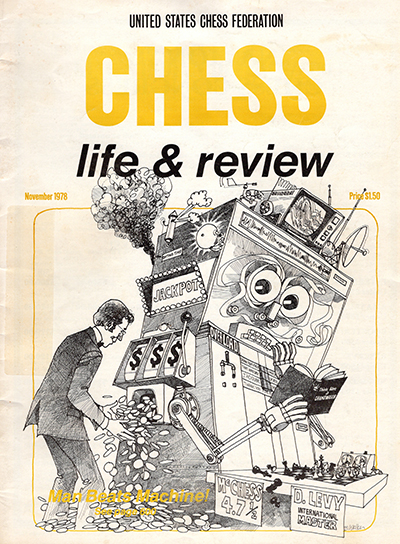

Then, by chance, he joined US Chess for the first time in 1978. Suddenly, our small chess library of a handful of books (which I treated as fetish objects, such was my intense desire for all things chess) was increased by the first copy of Chess Life that arrived at 225 Threadneedle Road: November 1978 with its headline of “Man Beats Machine!”

November 1978

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Cover used with permission of US Chess

I drank in this issue like a beast on the Serengeti finding a waterhole during a drought. I immediately read it cover-to-cover, then again many times over the years (yes, including the Tournament Life section; please don’t judge me). The cover art by Bob Walker—a mad scientist’s vision of a chess computer paying out a jackpot to IM David Levy—supports Levy’s story about how he defeated the computer CHESS 4.7. It all captivated my junior-high self.

As editor myself decades later, I was part of a team that created notable covers. Among them: April 2010 executed the concept of a cow standing on a chessboard field for a feature about rural chess, designed by our Art Director Frankie Butler—readers either loved or hated it, making it one of our most provocative covers. March 2016 showed GM Vassily Ivanchuk deep in thought, captured by the renowned photographer David Llada. November 2018, and the final cover I was directly involved in, presents GM Timur Gareev gleefully skydiving over southern California while wearing a checkered flight suit and holding a board with pieces. (There was even the tragicomic issue of October 2012 on which GM Ivan Sokolov is looking so unbearably glum that Conan O’Brien used this cover as comedic fodder on his late-night talk show).

Still from Chess Diving with Grandmaster Timur Gareev, 2018

Courtesy of US Chess

But as proud as I am to have added to chess literature myself, one never forgets their first love.

It is telling how many names contributing to this 1978 issue continued to work with me during my tenure 30, then even 40, years later. Bruce Pandolfini remains a columnist. GM Pal Benko retired as our endgame columnist a few years ago but still contributes the occasional feature. Jerry Hanken is listed as a US Chess Policy Board (now called Executive Board) member; he was one of my go-to reporters for major U.S. tournaments my first few years as editor. In the Tournament Life section, Bill Goichberg’s Continental Chess Association events still dominate the listings. Editor Burt Hochberg died while I was editor, and I had the sad privilege of publishing his obituary.

Once this Chess Life issue quenched my psyche, I was set on a path than now seems inevitable in retrospect. It pointed me towards the chess journalist path I continue to this day, allowing me to share remarkable stories about this extraordinary game.

Daniel Lucas, US Chess Senior Director of Strategic Communication

Parent Issues

My initiation into the chess world was through an observer’s lens, as perhaps is fitting for a writer/editor: I began as a chess parent. One day my nine-year old son was taking on and defeating all comers at a Renaissance fair; before I knew it, I was fretting and pacing along with hundreds of other parents at scholastic tournaments. I soon learned about pairings and how to read wall charts. I made friends with other chess parents. As time went on, I even began, somewhat, to “talk the talk.” But I never thought I would be anything but an involved chess parent who occasionally blogged about, well, life as a chess parent.

Until two years ago.

My current stint as publications editor for US Chess has been remarkable and unexpected. It began, innocently enough, when I answered an advertisement for an assistant editor position in February 2017. (To this day, I suspect I won the position because I emphasized that I was vigilant about deadlines.) Shortly after I passed the one-year mark, then-Director of Publications and Chess Life Editor Dan Lucas asked to meet with me. I suspected he might tell me I was ready to take on editing Chess Life Kids solo. But to my surprise, he instead passed the entire publications torch to me because he’d been promoted to a newly-created position within the organization.

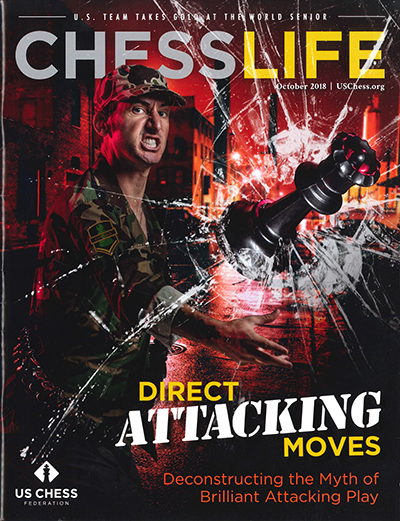

Luckily for me, Dan didn’t leave me floundering. His parting gift was a treasure trove of articles and cover ideas to see me through the rest of the year. I am proud of these early issues, especially because we produced three amazing and completely different covers in a row: a confident GM Cristian Chirila, National Open champion, posing for the talented Lennart Ootes (September 2018); a fierce FM Mike Klein, photographed and artfully stylized by Sean Busher (October 2018); and GM Timur Gareev gleefully skydiving from 10,000 feet holding a chessboard (November 2018). But even though these über-cool covers were released with my name on the masthead, they were, in fact, the results of effective guidance from Dan and outstanding art direction from Frankie Butler.

October 2018

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Chess Life cover used with permission of US Chess

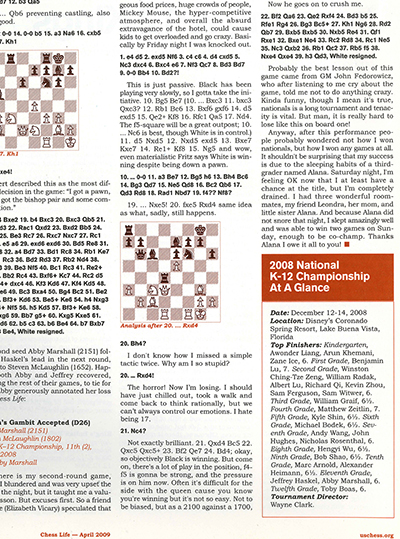

So, my all-time favorite issue has nothing to do with my nascent role as publications editor; it instead hearkens back to my initial role as a chess parent and the thrill of seeing my son’s name in Chess Life for the first time after he co-won the seventh-grade title at the 2008 National K-12 Championships. Yes, his name was in a tiny “At A Glance” box on page 28. No, his photo wasn’t plastered on any of the pages. But the April 2009 issue of Chess Life remains a touchstone to this day: it reminds me that what I do matters to readers and chess lovers of every stripe.

April 2009

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Chess Life used with permission of US Chess

Chess has been good to me. It helped pay for my son’s college education; it introduced me to some fascinating people, including my husband; and today it is a fulfilling career and source of endless education. Knowing that I follow in some mighty intimidating editorial footsteps, my hope is that one day a future player, parent, writer, or editor chooses an issue from my tenure—for whatever reason—as one that made a similar impact on them.

Melinda Matthews, Chess Life Editor

Looking Back

I always knew I would be a journalist, but I never thought I would have a love affair with the game of chess. In fact, I didn’t even know how to play the game until 1972…until Bobby Fischer. I think that time unravels before us as a ball of string. Eventually it becomes a thread of revelation. Looking back, I realize that 1972 set the stage for my opening chess move. I joined the San Diego Chess Club.

My opening strategy was simple. As a dancer, I used chess to balance the mental and the physical. Over time, I was able to combine chess and journalism. I worked at the San Diego Union-Tribune, wrote for different publications, and became vice president of the San Diego Chess Club.

Then time put on its running shoes. In 1978, I moved to Oregon, where I continued writing and became president of the Oregon Chess Federation. My opening repertoire was drawing to a close and my middle game was just beginning.

I moved from Oregon to New York in 1987 and started as assistant editor at Chess Life. The magazine was in a state of turmoil. I worked with three different editors over a short span of time and was about to face a fourth when the Chess Life staff took me aside and asked me to apply for editor. Well, back then men were at the front door when opportunity knocked, but women were usually in the kitchen. There had never been a woman editor at Chess Life. I received numerous letters of support and encouragement from chess players around the country, so it made me think. It would take hard work and it would take courage. I viewed this challenge as a great opportunity.

The Chess Life staff worked like a well-oiled machine. We won the Most Improved Magazine award from Chess Journalists of America, as well as commendations for interesting articles and colorful creative covers. And we did all the typesetting and editing without a computer, as ChessBase was brought in as I was leaving. But I am most proud of bringing grandmaster annotations and columns back to the magazine. I learned that during my editorship US Chess received more complimentary letters from readers of Chess Life than at any other prior time. Harold Winston, president of US Chess when I was hired, later said “…her last six issues can be favorably compared to any others in the history of Chess Life…I’m proud of the job she did.”

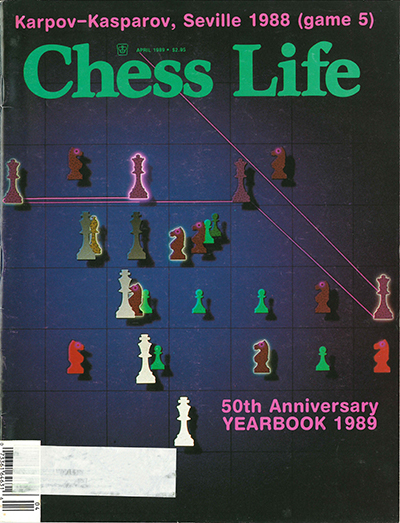

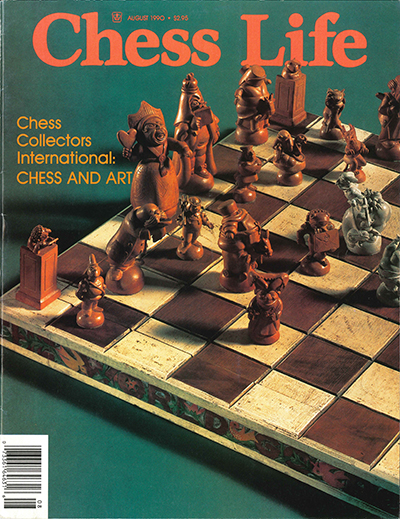

Do I have a favorite issue? I’m not sure. But I do have a few that stand out in my mind. The April 1989 issue will always be special to me for personal reasons; and I worked diligently on the content for the June 1990 issue, which debuted special instructional columns. Readers especially liked the August 1990 issue which contained: an artistic colorful cover; the debut of “Theoretically Speaking,” a new column written by GM Joel Benjamin, GM Larry Christiansen, and then GM-elect Patrick Wolff; “Larsen Wins in London” by IM Bjarke Kristensen; Luis Hoyos-Millan’s coverage of St. Martin; “U.S. Championship Playoff” by Frisco Del Rosario; GM Ron Henley’s article “The Voronezh Cultural Chess Festival;” “An Interview With Garry Kasparov” by Evgeny Rubin; New York Open coverage and games by Bleys Rose; GM Edmar Mednis’ superb column “How To Select Your Opening Repertoire”; IM Jeremy Silman’s instructive “The Art of Making Plans;” Frank Elley’s “The Measure of a Grandmaster;” as well as our regular monthly columnists: GM Andy Soltis, GM Larry Evans, Bruce Pandolfini, and David L. Brown.

April 1989

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Covers used with permission of US Chess

August 1990

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Cover used with permission of US Chess

I loved each day editing Chess Life. I interviewed seven world champions, covered national events, and became friends with grandmasters from all around the world, many who continued to write to me years after I left the magazine. I am thankful for my staff, and the columnists, writers, and photographers I worked with during my tenure.

The past is like a time tunnel. Heading into the end game, I can fast forward and rewind past and present to question, to remember, to weigh, to estimate and to judge. Today’s technology was only a dream in the making in the late 80s. Who knows what we will see in the future? I always knew I would be a journalist…but I didn’t know I would have a love affair with the game of chess.

Julie O’Neill, Former Chess Life Editor

Chess Kaleidoscope

Most Americans who take chess seriously remember when they first read Chess Life. That was when the magazine was at its best, they say. Chess was new and exciting to them then. Looking back, I can see that the Chess Life I first encountered nearly 60 years ago was not a very good publication. But I loved it—mainly because of Eliot Hearst’s column.

American chess was much smaller then, and so was Chess Life. The January 1962 issue had only 20 pages and the next issues had 24 each. When the latest issue arrived in the mail, I quickly flipped past the pages of “house ads” and promotional material (“USCF membership is the best buy in

chess”) as well as the self-congratulating articles by Larry Evans and Sammy Reshevsky, who annotated their own games as if they were imparting deep instructional wisdom.

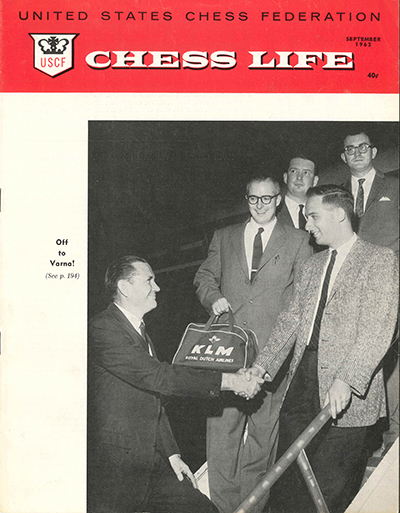

September 1962

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

Cover used with permission of US Chess

I did not care about that. I wanted to find the page headlined, “Chess Kaleidoscope,”—the Hearst column. I was new to chess, but I could tell I was reading something unlike anything that was appearing in America. (Or abroad, as I later found out when I subscribed to British, Russian, Yugoslav, and other chess magazines).

Hearst could mix perceptive insights with a kind of chess news, in the style of the three-dot journalism that appeared in newspaper gossip columns. He did some original reporting, such as in August 1962 with his interview of Richard Cantwell, a Virginia dentist and avid chess amateur. Cantwell had spent his summer vacation at the Candidates Tournament on the island of Curaçao, where he snapped some of the best photos ever taken of top chess players and provided fascinating insights into what grandmaster chess was really like.

In other columns, Hearst would run snippets culled from his various sources, each separated with an ellipsis: How Pal Benko was in time trouble five times in his 106-move game with Hearst in the recently-completed U.S. Chess Championship and succeeded in rewriting endgame theory…How Viktor Korchnoi considered himself a serious runner because he could do the mile in seven minutes….How Mikhail Botvinnik said he gained weight during his 1960 World Chess Championship “because my head functioned poorly.”

1960 Gold Medal Winning Student Team, Leningrad, USSR, August 1, 1960

Collection of US Chess

Pictured from left to right: Eliot Hearst, Raymond Weinstein, Jerry Spann, William Lombardy, Edmar Mednis, and Charles Kalme

There were a few other good things about Chess Life then, such as Botvinnik’s annotations of his quickly-famous game with Bobby Fischer from the 1962 Chess Olympiad. But my favorite articles that year were written by Hearst. One was his riveting account of serving as captain of a U.S. Olympiad team that barely made it to the Bulgarian playing site and then nearly carried off medals. When I grow up, I said, this is how I want to impart the drama of chess.

The other Hearst masterpiece appeared in his July 1962 column. His “Gentle Glossary” was an ironic look at chessplayers. He defined an “amateur” as “someone who only plays for money.” A “professional,” he added, is “anyone who cannot make a living playing chess.”

There was little interaction with Chess Life readers in those days. But that column struck a chord. Readers responded in October with their own whimsical definitions. An “annotator” is “a grandmaster of clichés,” one wrote. A “Giuoco Piano” is “playable but not quite so good as a Steinway,” said another. And “analysis” is “irrefutable proof that you could have won a game you lost.”

I only got a few chances over the years to meet Eliot and tell him how he had inspired me and how I had tried to make my Chess Life column as good as his. I last saw him in 2014 when the Marshall Chess Club had an evening to honor previous champions of the club (he was the 1952 champion).

He told me how he had accidentally met Fischer long after Bobby’s world championship match, when he had disappeared from chess. Fischer wanted to have dinner. Eliot agreed and then had to listen Fischer rant about various non-chess topics. When Fischer was done, he asked if they could analyze some chess games together. “But Bobby, you were always better than me,” Hearst said. “What can I add?”

“You can learn from everyone,” Fischer replied.

When I heard in 2018 that Eliot had died, I remembered that story. And how much I had learned from him.

Grandmaster Andrew Soltis, U.S. Chess Hall of Fame Inductee

US Chess Timeline

US Chess History, Part I: The Early Years (1939-1959)

US Chess History Part II: The Fischer Boom (1960-1979)

US Chess History Part III: America Rising (1980-1999)

US Chess History Part IV: A New Golden Age (2000-2019)

Presenting Partner:

Press

10/21/2019: US Chess — Masters of the Arts: Tony Rich Interviews Carol Meyer

6/14/2019: Classic 107.3 — World Chess Hall of Fame (podcast)

5/23/2019: St. Louis Public Radio — On Chess: US Chess Federation Celebrates 80th Year and Looks to the Future

4/9/2019: US Chess — One Move at a Time with April Guest Emily Allred

3/15/2019: FOX 2 — Weekends on the Web: Saturday and Sunday, March 16-17, 2019

3/6/2019: FOX 2 — Tim’s Travels: World Chess Hall of Fame new Exhibit (video)

3/5/2019: Press Release — World Chess Hall of Fame Exhibit Honors the 80th Anniversary of the US Chess Federation

2/15/2019: Tennessee Chess Association — 100 Year Old Memphis Artifacts Visiting World Chess Hall of Fame